Issue #7

Entangled Topographies

Merve Gül Özokcu, Pelin Tan (Eds.), Ruken Aydoğdu, Özge Çelikaslan, Leyla Keskin, Yelta Köm, Yıldız Tahtacı, Mezra Öner

CATEGORY

Welcome to Issue #7: Entangled Topographies, guest edited by Merve Gül Özokcu and Pelin Tan. Entangled Topographies presents how the research collective Arazi Assembly is working in different spatial scales focusing on the Southeast region of Turkey. Arazi considers collective research as a form of knowledge production of decolonisation, care, and solidarity.

With urban and architectural backgrounds, Arazi researchers’ trajectory questions how any scale of infrastructure as an agency functions and creates an assemblage of entities that re-structures and colonises the territory. Arazi aims to understand and develop uncommon methodologies of architecture, urbanism, and territorial research.

The term territory indicates a process, not a solid substance, and its “entangled matter formation” can force us to face its unthinkable experience of conflict zones and territories. The unthinkable representation is about the fluid and entangled matters of formation of territories that invite us to think of transversal methodologies and narratives of decolonisation. Does the unthinkable precede the entangled matters of infrastructures in/under conflict zones of territories? The question of the extractive capitalist formation of places in the constellation of the region, the cities such as Batman, Mardin and Diyarbakır, and the towns such as Nusaybin, Midyat, Lice, and Hasankeyf, is revealing simultaneously the questions of territorial control infrastructures and extraction in multiple means. A relational episte-ontology that structures the entanglements, may enter and provide an aesthetic tool of responsibility in the era of geontopower. This collective project and practice aim to look into an experienced field of conflict zones where matter is entangled in time, and in which surpassing the trauma is the ongoing process-based materiality. This region is reproduced through several forms of state of exceptions. Territory always refers to a particularly modified controlled zone as a state of exception.

The “State of Displacement: Entangled Topographies” project produced visual narratives on zones of dispossession and displacement in the region around Tigris river. A selection of Arazi Assembly’s collaborative works from the mixed-media outputs ranging from videos, photographs and drawings, to critical cartographies and materials published since 2015 focuses on places and people usually understood through the lens of disaster in the more-than-human world and the state of displacement. Through archiving, witnessing, and engaging practices of urban, rural and threshold spaces in terms of spatial justice, the researchers are focusing on various cases of spatial scales. From Kurdish female farming practices, to undocumented migrants living across borders, new housing projects that are displaced local neighbourhoods via urban conflict or waterdams, rescaling of lands and pastoral practices as animal herding, practices of commons and their relation with the non-human world.

Practices of commoning are various in different conditions and scales. Especially, in the Southeast Turkey region; the conditions depend on urban and rural policies, continuous military surveillance and border regimes. The territorial specificity here is marked by forced migration in the region, as well across the borderlines.Scales influence the place-based practices. The notion of scales spans from urban to rural spaces and more than various practices of commoning. Here “scale” is also not only a physical element as often understood in design and architecture, but also about how it is politically conceived. Each commoning practice differs between rural, urban, and border scale. Furthermore, the ethnic and class structures as well as tribal and religious backgrounds of communities influence the creation and sustaining of the commons. In Ruken Aydoğdu’s research, Kurdish female farmers and foragers at the hinterland of Hevsel Gardens, the historical centre of Diyarbakır city, are explained through architectural anthropological field research and engagement. Through a critical eco-feminist approach, the argument here is that these dispossessed women in precarious situations are not only trying to survive on daily basis by creating orchards, selling vegetables and various edible weeds, but also resisting the urban policy of this hinterland’s destruction by creating entangled labour and production that sustain the biodiversity of Hevsel. On the other hand, Merve Gül Özokcu’s research is about the “spatiality” of commons and the memory of space created/traced by the Kurdish women according to their daily/annually food production. In both cases, precarious female labour and its spatiality create both tangible and intangible heritage in order to sustain the commons of a more-than-human world, biodiversity, and ecologies in and around Diyarbakır and the Hasankeyf/Mardin region. Özge Çelikaslan’s text “Re-imagining the archival commons” means to contemplate new archival methodologies collectively considering the needs of the societies, commons, and the environment.

How do we approach Arazi in recent spatial practices? How does it speaks to us? And what is its methodology and fiction? Arazi as an Arabic-origin Ottoman word has many meanings such as land, country, terrain, territory, estate, property, soil, ground, agricultural land, demanded land, etc. From a linguistic perspective, the word based on “Arz” means “supply”. Another origin of reference is maybe “Araz”, which may mean “symptom”. In English, we as a research collective prefer to use Arazi as an equivalent word to “territory”, which maybe won’t fully correspond to it; because the direct translation of “territory” means “regional” (bölge) or territorial in Turkish. Arazi is often understood as “tabula rasa”. An empty plot in urban or along the infinite space in Anatolian cities. Abandoned land, demolished land, a geological space with soil, stones and sometimes garbage without a trace of human action and history. An innocent space. Sometimes a ruin. We aim to bring back this word both in perspective of “territory” and the concept of how we understand today’s critical spatial research and practices.

The effects of war and the negotiation of borders transform our approach and methodologies of infrastructures that are not only functional thresholds of architecture, but also instrumentalise new conditions that are part of geontologies of the landscape. Referring to Povinelli; geontologies are two terms: geos (non-life) and ontology (being), “currently in play in the late liberal governance of difference and markets” [1]. She proposes a new definition of biopolitics where there is no separation between elements of Life and Non-life; moreover, this conceptual combined approach is based on new figures, tactics, and discourses of power (ibid.). From this theoretical perspective, how we can approach the infrastructure of the landscape shaped by war and migration? What is the base to discuss such extra-territorialities through and with “Things”? Infrastructure is basically a term for designing modern urban space and is also the production of complete spatial objects. For centuries, it has had basic roles such as colonisation; that is introducing projects of infrastructure in order to change and colonise the culture or society on any scale. It also functions as a justification for neoliberal urban-rural policies in expanding, expropriating, and rescaling property and lands.

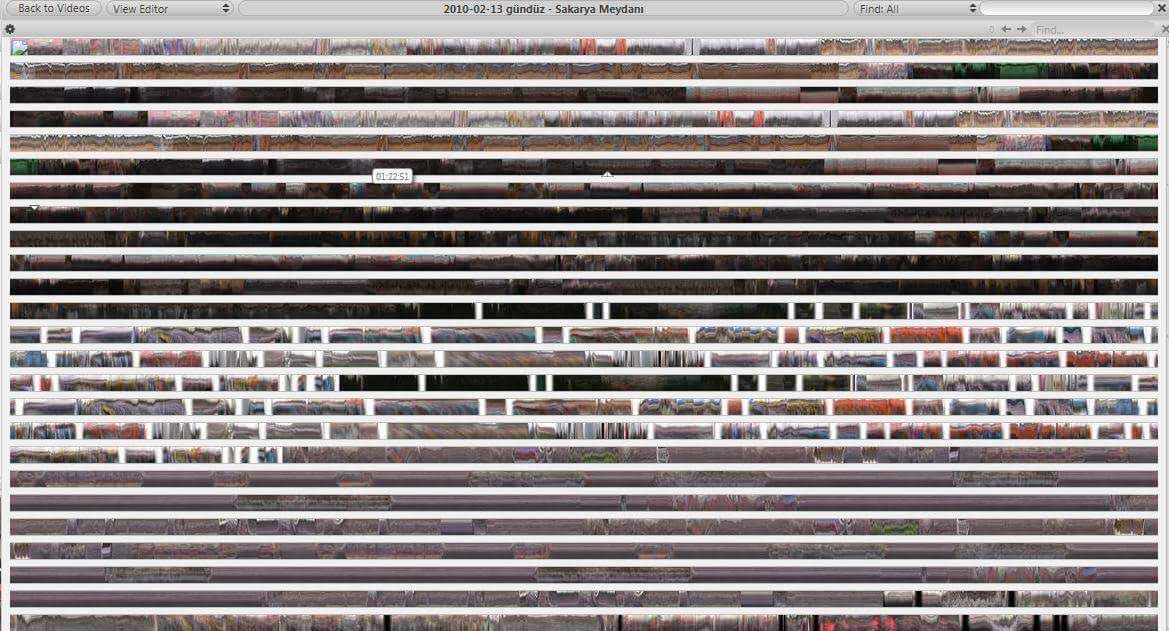

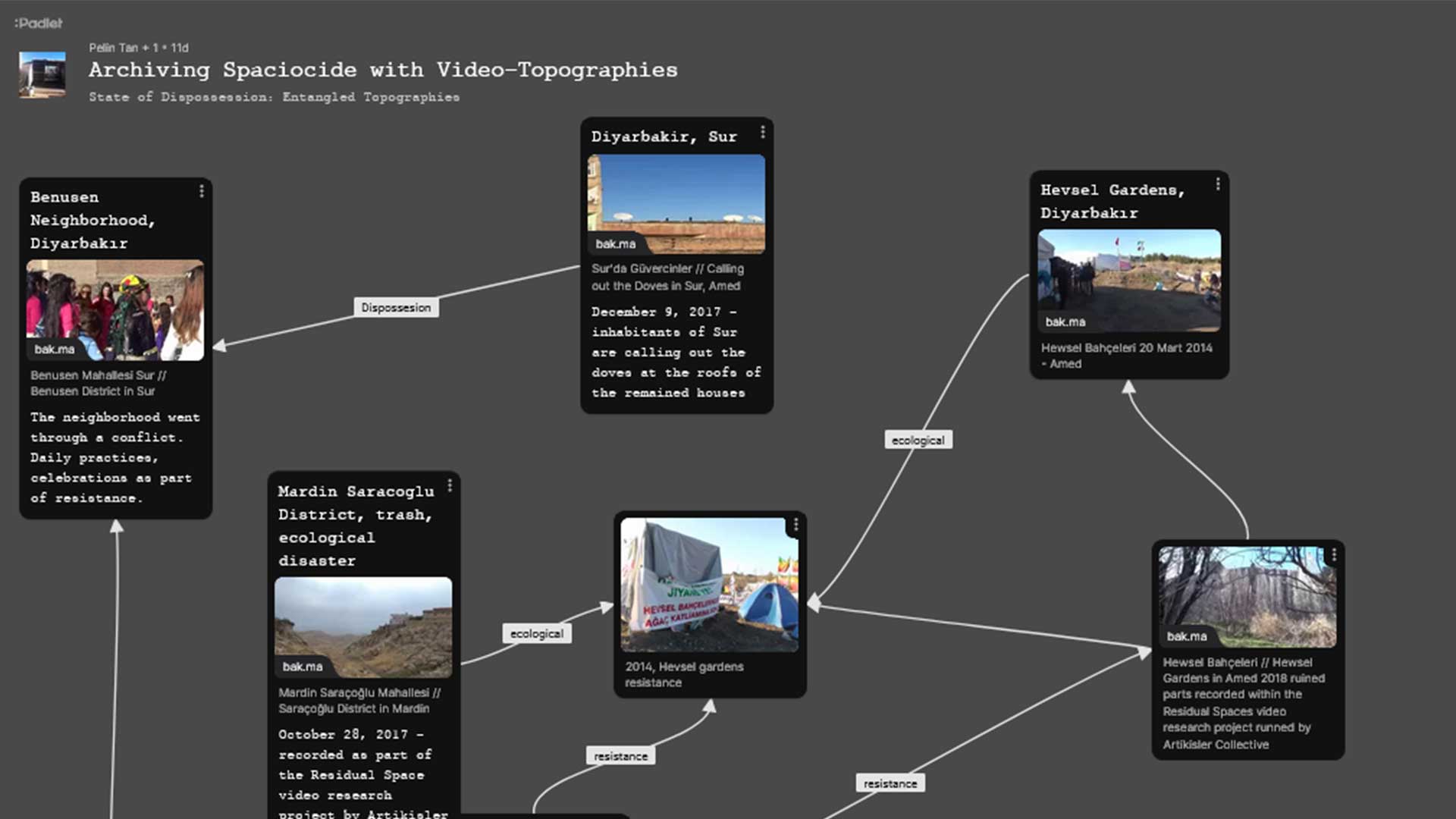

Recently, the discourses on infrastructure reveal the role of infrastructure in more complex ways. Incompletion and failures of infrastructure projects are often related to strategic processes of delay and prolonging. The process becomes more important (than the complete infrastructure itself) where actors such as the state, local governments, developers and citizens debate or negotiate, leading to more profit and surplus. In short, instead of the complete object or presentation itself, the incomplete, continuous failure of the process of infrastructure becomes the vital part. It is most often argued that in many cases (for example in Indian cities), the failure of infrastructure or interruption of infrastructural function brings co-existences of alternative ways of infrastructure in the network of such cities. Infrastructure as an assemblage is another current discourse on infrastructure. As Graham describes: “…urban infrastructures as complex assemblages that bring all manner of human, non-human and natural agents into a multitude of continuous liaisons across geographic space” [2]. In the text “Archiving Spaciocide”, Pelin Tan and Özge Çelikaslan put forward an assemblage of their video archive that consists of residual spaces, connecting it to many spaces in Southeast Turkey which witness assemblages of the spaciocide in the socio-spatial network. Merve Gül Özokcu, in the text “Narratives of Spaces”, offers an open source database of visual and oral narratives of collective spaces of cooking and commoning.

Since 1924 with the establishment of Şark Islahat Planı or Orient Reform Plan, assimilation or Turkification of Kurds found legal grounding. One of the assimilation policy tools was reforming the settlement. Previously, the region faced the Displacement Law that evicted and forced the displacement of Armenians on 27 May 1915, rescaling the land and deterritorializing urban neighbourhoods, villages and farming areas of the local people. This law constituted a strategic spaciocide in the region. Dispossession is a process that provoked the displacement of Armenian, Kurdish, Ezidi, Suryani and other communities of villages and urban sites since the last century. The ongoing transformation of the territory has been continuously caused by urban housing projects, expropriation of property, and rural land policies of eviction and displacements. Arazi researchers are focusing on various scales of territory, borders, neighbourhood, and infrastructure. In “A road to Home”, Yelta Köm is working on an ongoing visual investigation of the concrete blocks that were used, and how they are shaping the spatial surveillance in urban areas and border zones. Yıldız Tahtacı is working on the Benusen neighbourhood, a site beside the Diyarbakır fortification that was expanded with the migration of Kurdish communities whose villages were burnt during the 1990s. The project presents the commoning practices by women who created a laundry as common space, where they could meet and do other activities. This text presents a video essay on the historical Sur neighbourhood of Diyarbakır during and after the conflict in 2016. Sur is a thousand-year-old district that hosted various communities who were evicted in the 20th and 21st century. Since most of it was destroyed during the conflict in 2016, the new housing project initiated by the government cleaned almost entirely the identity and heritage of Diyarbakır. As many inhabitants were forced to leave, the district became a means of housing speculation and the socio-spatial heritage has been replaced with new buildings. Benusen neighbourhood, located in the outskirts of the historical wall of the center of Diyarbakır, is a neighbourhood of evicted Kurdish communities who had to migrate from their villages in the 1990s. Benusen women’s laundry center as a common place is depicted in this essay as a place of commoning that was closed by the state. Yıldız Tahtacı and Mezra Öner exemplify another town, Nusaybin (Nisibin), a Kurdish town bordering Al-Qamishli / Syria that faced the same process of spaciocide, a state-led transformation and expropriation of urban areas, now filled with new housing projects. Both video essays depict the daily life of streets and the loss of intangible heritage, they are witnesses of topographies, and they create a visual archiving of the transformation of spatial environments. In Şikefta, Heskif text, Leyla Keskin explains the effect of the state-led water-dam project on the Tigris River that forcibly led to the disappearance of the biodiversity and more-than human world ecology of its region. Thus, she tries to find a language of ecological mourning that connects the indigenous ecological struggle of the more-than-human-world.

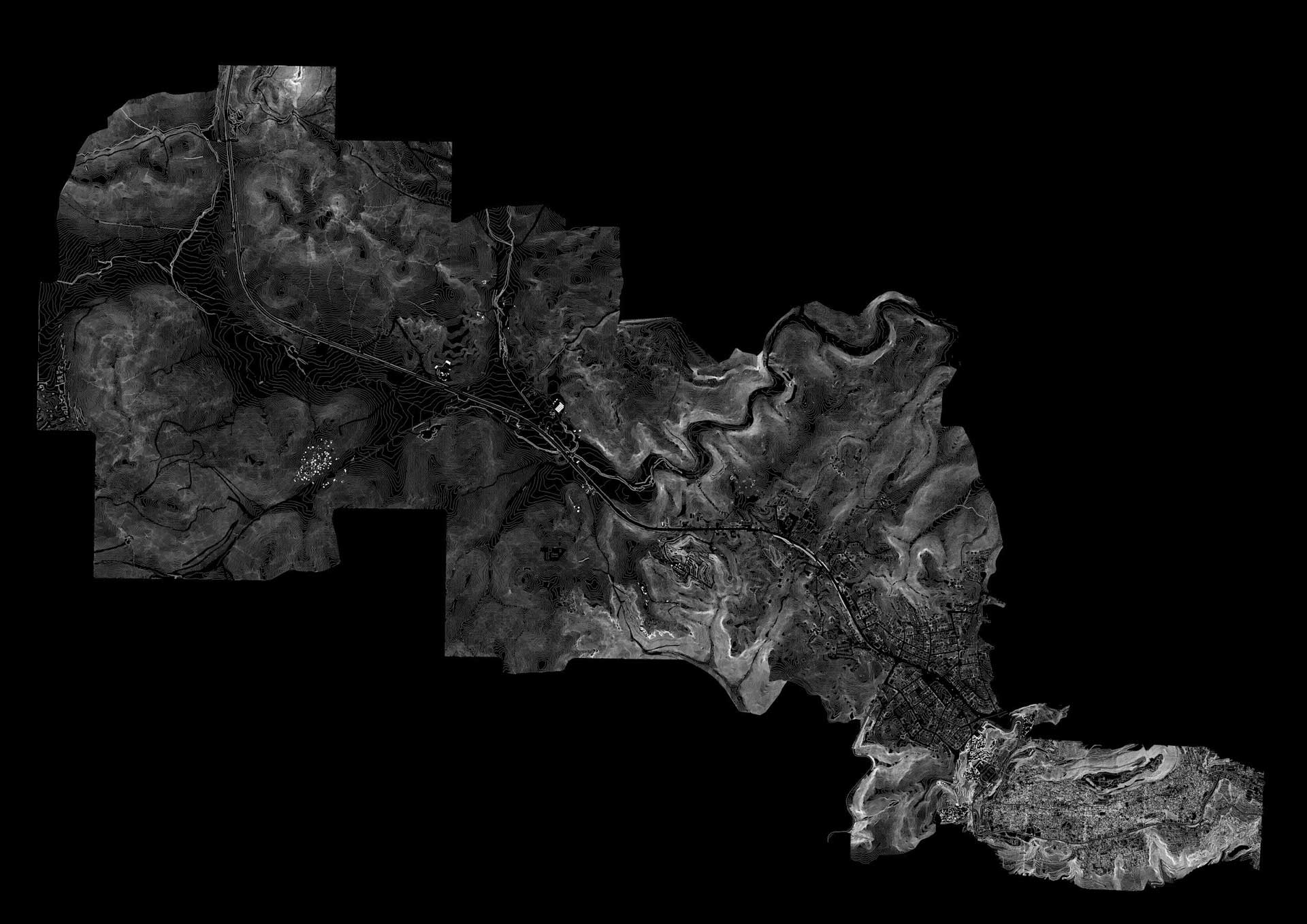

How does this process relate to cause and effect not only through humans but also non-humans? So, a specific empirical knowledge is acting with a relational phenomenology in our engagement in place and space.Entanglement as a discursive methodological tool may lead us into a phenomenological approach, describing the phenomena from a contra-division of human and matter, or subjectivities and territories. In our collective engagement in space and place we refer to the Agential experience and entanglement of Karen Barad [3]. Phenomena for Barad is an agential intra—actions of multiple apparatuses of bodily production. Furthermore, Barad notes that phenomena should not be understood in a phenomenological sense but as particular material entanglement. The notion of resilience is a crucial issue in entanglement. The differences of the ontological between “entanglement” and “assemblage” is that entanglement is more a material engagement with an effect on related entangled existences; whereas assemblage is referring more to visual epistemology where fragments and layers are orchestrated. Barad neither refers to inter-action nor dependency: “The notion of intra-action is a key element of my agential realist framework. The neologism ‘‘intra-action’’ signifies the mutual constitution of entangled agencies. That is, in contrast to the usual ‘interaction,’ which assumes that there are separate individual agencies that precede their interaction, the notion of intra-action recognizes that distinct agencies do not precede, but rather emerge through, their intra-action. It is important to note that the ‘distinct’ agencies are only distinct in a relational, not an absolute, sense, that is, agencies are only distinct in relation to their mutual entanglement; they don’t exist as individual elements”. For Barad, “agency” is not an attribute of something or someone; rather it is the process of cause and effect in enactment: agency is ‘doing’ or ‘being’ in its intra-activity. It is the enactment of iterative changes to particular practices – interactive reconfigurings of topological manifolds of space time matter relations – through the dynamics of intra-activity. For her, materialisation is a process, a relation of production, a reconfiguration of the material-social relations of the world. [4] Methodologies of critical spatial practice in our research are important but are not enough to understand the process of matter; especially in extra-territorialities where the violence-informed knowledge is embedded. Topographies of stones, food, maps, borders and thresholds acting as agencies reveal the folded layers of oppressed knowledge of human and non-human relations and the violence of places. In the text “Inaccurate Topographies of Territorial States”, Yelta Köm explains how surveillance and control over territories re-form the topography. On the other hand, in “About cooking”, Merve Gül Özokcu expresses that ingredients, preservation, and cooking practices relate not only to daily needs but also to the storytelling and social co-existence of local daily resistance. In “When stone speaks”, Pelin Tan reveals non-human elements and the narrative of them within human relations creates a specific entanglement, where the trauma of slow violence and lost speech reactivates itself.

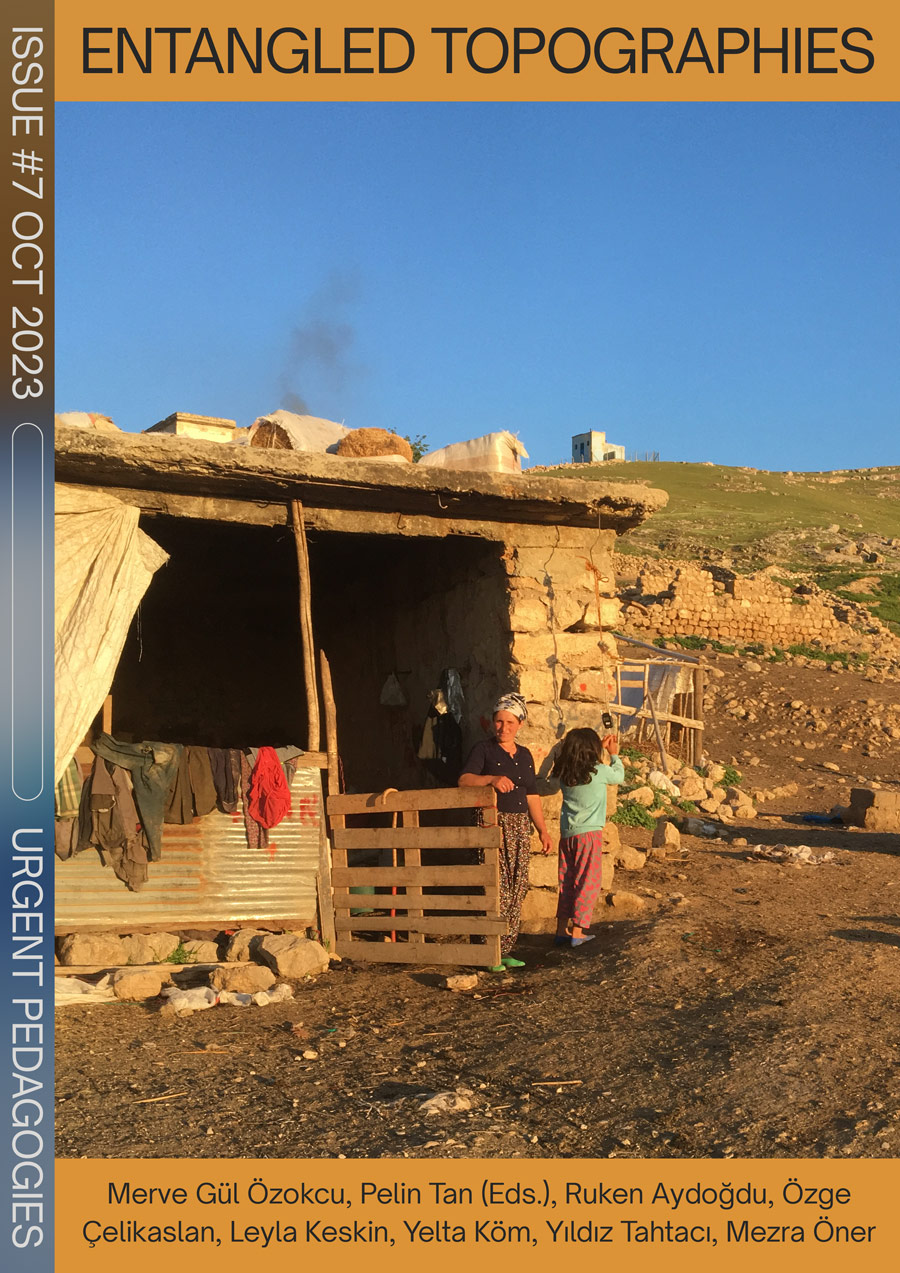

A Yezidi woman between stone walls of a cave where she was born. Photo: Pelin Tan

Contents

Eco-Healers / The Women of Hevsel

Ruken Aydoğdu

A commune in time, The commune in geography

Merve Gül Özokcu

Re-imagining the Archival Commons

Özge Çelikaslan

Archiving Spaciocide: Video — Topographies

Pelin Tan and Özge Çelikaslan

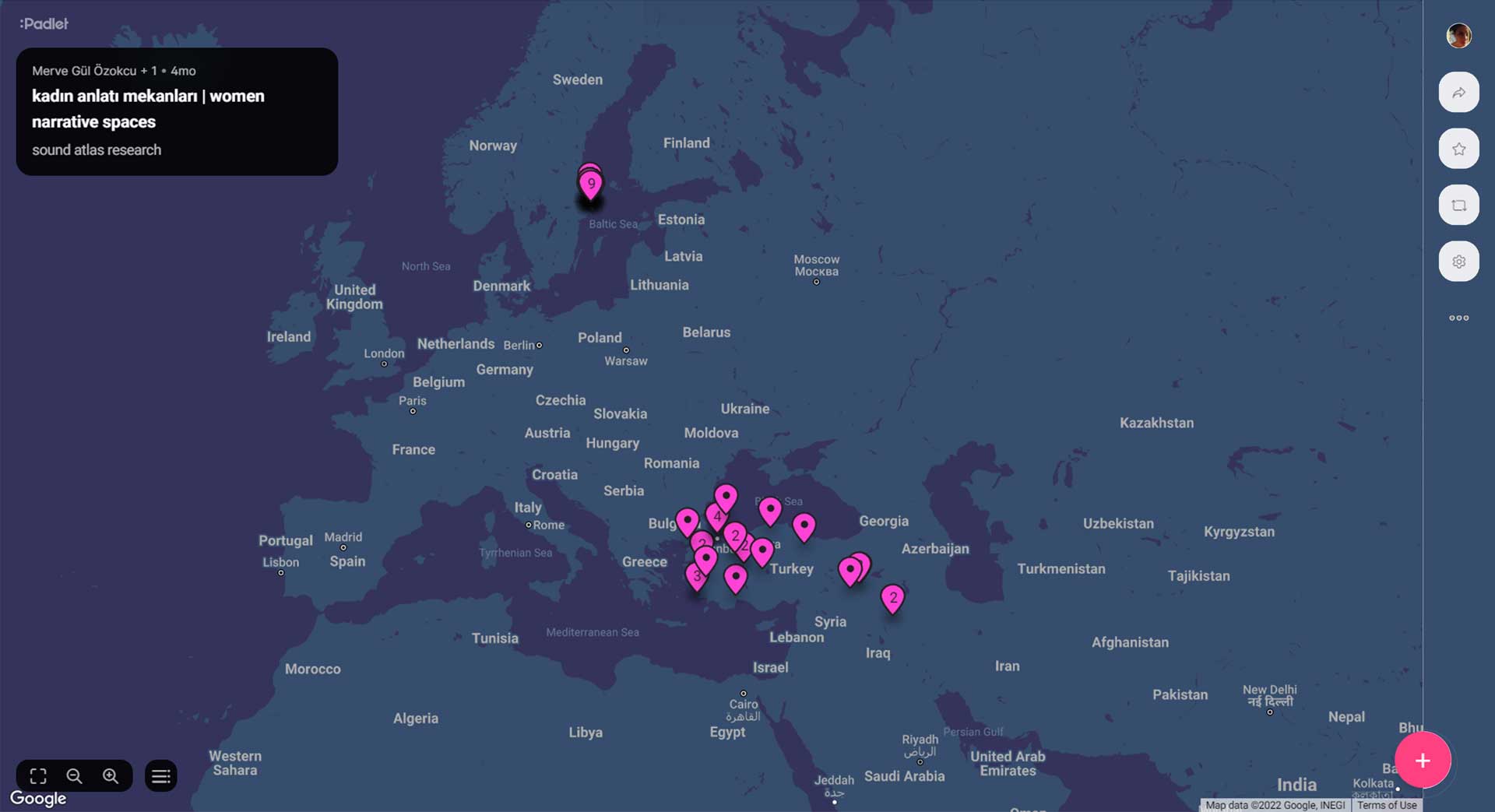

Narratives of Spaces: The gaze of the signifier, participation in an ongoing research

Merve Gül Özokcu

A Road to Home: Following the concrete

Yelta Köm

Benusen Neighborhood

Yıldız Tahtacı

Ecological Mourning: Extinction of fish in Tigris river

Leyla Keskin

A Border City Without Borders

Yıldız Tahtacı, Mezra Öner

Inaccurate topographies of territorial states

Yelta Köm

About cooking

Merve Gül Özokcu

When stone speaks

Pelin Tan

1.

Elisabeth A. Povinelli, Geontologies – A Requiem To late Liberalism, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2016.

2.

Stephen Graham, Edt., Disrupted Cities: When Infrastructure Fails, Routledge, 2010.

3.

Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, Duke University Press, Durkheim and London, 2007.

4.

Agency, Felicity J. Colman, https://newmaterialism.eu/almanac/a/agency.html

is the 6th recipient of the Keith Haring Art and Activism and a Fellow of Bard College of the Human Rights Program and Center for Curatorial Studies, NY, 2019-2020. She is a sociologist/art historian/film director based in Mardin and is currently a Professor in the Fine Arts Faculty of Batman University, Turkey. Pelin Tan is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Arts, Design and Social Research, Boston; and a researcher on Space and Anthropocene at the Architecture Faculty, University of Thessaly, Volos (2021-2026). She is a lead author of the Urban Society report edited by Saskia Sassen & Edgar Pieterse (Cambridge Univ.Press, 2018). Along with Anton Vidokle, Tan got the Sharjah Film Platform grant for their current short film “Gılgamesh: Who Saw the Deep” (2022).

is an architect, researcher, and activist. Her research focuses on commons, creative actions, narratives of everyday life, and indigenous eco-feminist practices. She is a member of Herkes İçin Mimarlık (Architecture for All) Association that aims to resolve social problems through architecture while searching for alternative ways of practising the discipline. She is a PhD candidate at the Architecture Design of İstanbul Technical University with the research entitled Women Narrative Spaces. Merve Gül Özokcu was a grant holder of IASPIS and İstanbul Cultural Art Foundation’s Design Resilience Program.

is a researcher/architect. She works with topics such as the city, architecture, ecology, and feminism. She is the co-founder of RE-Design Architecture. She focuses on visible spaces of violence in the city of Diyarbakır, where geographies of violence are present, through stories that take place in these spaces, the archaeological/architectural layers, the forms of resistance, and how it appears to us. She tries to make it visible through art practices. She is a member of the Diyarbakır Chamber of Architects. In 2021, she was one of the researchers supported by the US Consulate of the “Designing Resilience” project in partnership with CAD+SR (the Center for Arts, Design, and Social Research) and İKSV’s Design Biennial.

is a practitioner-researcher specialising in collaborative media production, participatory audiovisual research methodologies, audiovisual heritage of social movements, and media historiography. She has been involved in projects that foster collective filmmaking, visual ethnography of local and urban transformation, political conflicts in border zones, and autonomous trans-media. She is co-founder of the digital media archive of social movements bak.ma that emerged in the Gezi Park protests (2013). She is co-editor of the books; Surplus of Istanbul (2014, free pub.) and ‘Autonomous Archiving’ (dpr-barcelona 2016, 2020), and she has contributed to publications on film, video, activism, and archiving.

is an artist and painting teacher in middle school. Her research is focusing on the extracted geographies of Southeast Anatolia. In her practice and artistic research, she deals with spatial production, temporality, memory, and belonging. Ecological Mourning is the main theme in her practice and research, with her field research centred in Ilısu Waterdam and the Tigris Valley. She researches dispossessed lands, cultural heritage, agro-ecological practice as resistance, and rights of rivers. She is completing her masters degree on the topic of Ecological Mourning and Hasankeyf in the Visual Communication Design program at Mardin Artuklu University in 2022. In the meanwhile, she conducts pedagogical studies on Visual Arts and Drama for children in the age group seven and sixteen.

is a Berlin based artist who brings together architectural, artistic, and spatial practices to discuss social and political issues. His work is centred around landforms, technology, critical approaches to environment and communities, urban surveillance methodologies, data mapping systems, architectural technologies, oral and cinematographic storytelling, and the questioning of representation techniques. He is a co-founder of Herkes İçin Mimarlık (Architecture for All), a non-profit organisation devoted to offering approaches to social problems in Turkey from an architectural perspective. Yelta Köm is currently working as a research associate and teaching at the Practices and Politics of Representation chair of Bauhaus Universität Weimar Faculty of Architecture.

is an urban planner; completed her thesis Spaces of Commons of Dispossessed Women: Women’s Laundry House of Benusen Neighborhood/ Diyarbakır and The Women’s Center/ The Square at the Fawwar Camp/West Bank (Palestine) under the Supervisor of Assoc. Prof. Dr. Pelin Tan (Mardin Artuklu University – Architecture Faculty). Yildiz’s research trajectory is about ecological feminist approaches on architecture, urbanism and spatial practices. Between 2013 and 2017, she worked at the Urban Planning Department of Diyarbakir Metropolitan Municipality and, among many other positions and commissions, she has been a delegate of Diyarbakır Branch of the Chamber of City Planners TMMOB (Union Of Chambers Of Turkish Engineers And Architects).

is an urban planner. Her research focuses on the geography of trash/waste, Z. Bauman and biopolitics, and the anthropocene. She completed her master degree in Politics and the Geography of Trash/Waste at the Master Program of Architecture at Mardin Artuklu University under the Supervisor of Assoc. Prof. Dr. Pelin Tan. She is a grants manager of International Medical Corps Turkey, an international humanitarian aid organisation for Refugees in Turkey that provides medical and outreach support to cross-border. She is responsible for conducting projects on the field, coordinating with local NGOs. She was the Project Coordinator of Mardin WasteWater Treatment Plant Project on behalf of Mardin Metropolitan Municipality for two years and she is a member of the Chamber of City Planner and Association of Human Rights in Diyarbakır.