A Border City Without Borders

Yıldız Tahtacı, Mezra Öner

CATEGORY

“The increasingly sharpened/dividing state border could not break the kinship and cultural unity between the two cities.”

From the earliest times of humanity or society, everything has had borders and lines to define property. The determination of sovereignty areas with borders has been seen since the first state forms. The nation state, on the other hand, defined regional and local differences within its borders under a single national identity. Thus, ethnic and cultural identities were assimilated and colonised under a national identity.

Nusaybin (351 A.D.) was founded as a border city of the Roman Empire; it was included in the interior of the Ottoman period, an important trade passage and an old religious settlement (due to Mor Gabriel and Kartmin); it has been an important border city since the establishment of the Republic of Turkey.

The city was settled by the French during the First World War, and the settlement of Qamışlo (Qamishli), which is now on the Syrian side, began to be built about 3 km away. The borders of Nusaybin and Qamışlo, which share kinship ties, ethnic, and cultural similarities and unity, were determined by the Ankara Agreement signed in 1921. The border, which was managed with a single fence between 1928 and 1954, was mined after 1954. Between 1938 and 1954, the border was managed with flexible security at the gate, infrequent border outposts, and infrequent ambushes. Between 1952 and 1954, outposts became more frequent, the number of ambushes increased, and mines and wires were laid. After 1980, the district’s relationship with the border became increasingly political.

Nevertheless, the increasingly sharpened/dividing state border could not break the kinship and cultural unity between the two cities. Cross-border kinship and marriage relations are still strong. These groups in different sovereign states continue to preserve their cultural identities despite assimilation policies. In spite of the dominant national culture, the predominance of the common cultures of both cities reveals the state of borderlessness. The resulting state of borderlessness has created the definitions of ‘Serxet’ (above the border) and ‘Binxet’ (below the border) against the reality of Syrian land or Turkish land. In this context, it is seen as a part of the land and culture despite the increasingly sharpened physical border.

In the 1990s, with the emergence of the conflict process, crossings between the two cities began to be controlled on security grounds. In 2015, the Ministry of Interior Affairs established a joint project called “security belt” with the governorships of Hatay, Gaziantep, Kilis and Şanlıurfa to create a security belt on the Syrian border. The aim of the project was to prevent illegal crossings of the border trade with the culture of kinship-coexistence between the two cities and to ensure security. According to the project, the 911-kilometer border between Turkey and Syria was built with concrete walls (Israeli concrete wall) with an average height of 3.5 meters.

While the hot war was raging in Syria, urban warfare broke out in Turkey’s Kurdish cities in 2015-2016, leading to two years of curfews and a process of destruction and reconstruction. In Nusaybin, clashes broke out in six neighbourhoods and severe war conditions emerged. After the end of the clashes, curfews continued in the cities, residents were prevented from accessing their homes indefinitely and displacement began, leading to forced migration to other neighborhoods and cities. Neighbourhood areas where the clashes took place were demolished with hasty expropriation decisions and turned into completely empty areas. Immediately afterwards, a great construction activity started. Interventions were made in the settlement and population mobility of the city through urban transformation legislation. Spatial transformation and ‘rehabilitation works’ started in these oppositional neighborhoods. With this spatial transformation process that emerged in the neighborhoods of Nusaybin settlement close to the border, it was ensured that they were placed in an area far away from the borderland Qamıshlo. Thus, two related cities that the state border could not divide/separate were tried to be separated from each other through dispossession and displacement in the context of urban transformation and expropriation laws.

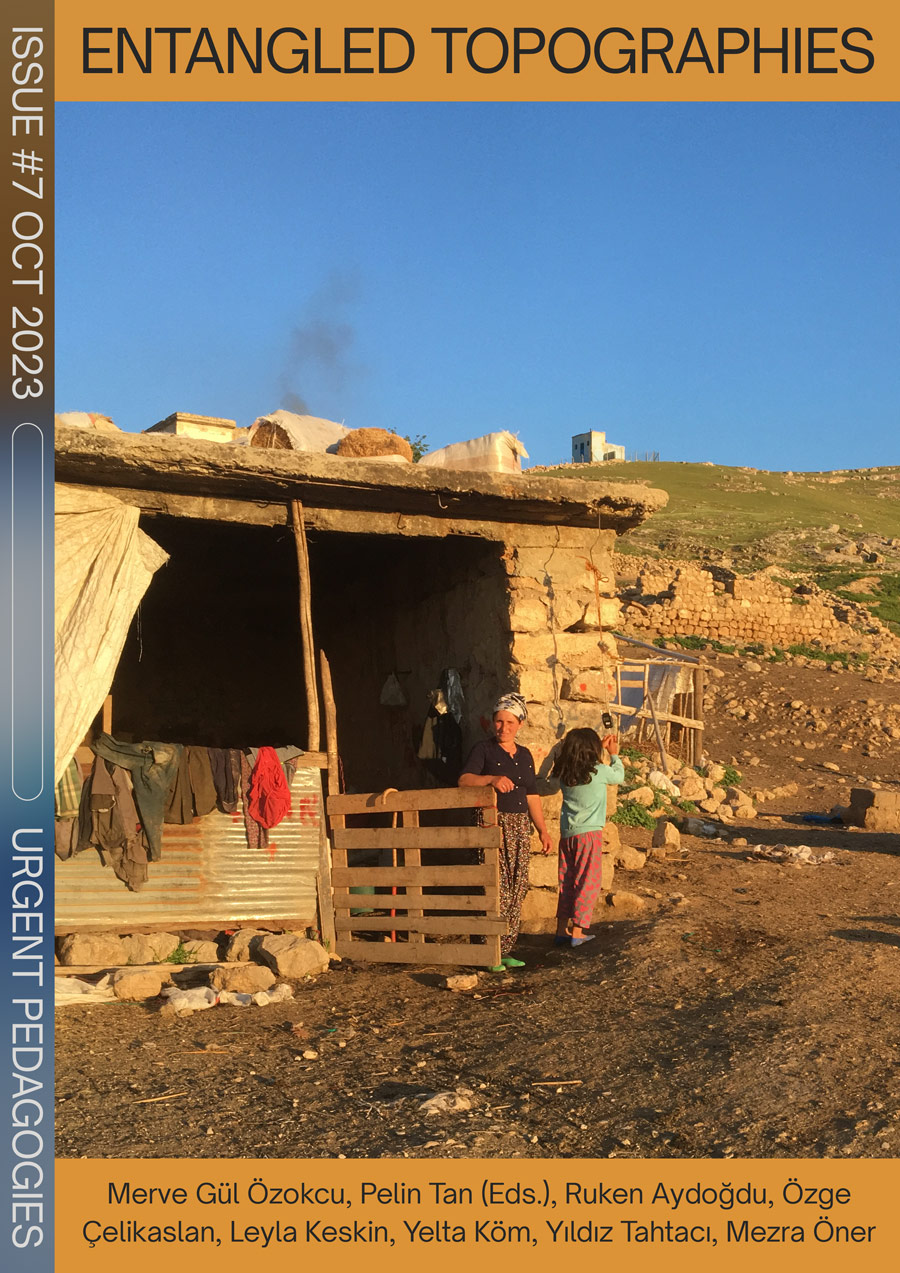

Festive celebration at the Nusaybin Qamishli border. Photo: http://www.ilknethaber.com/suriye-sinirinda-ucurtma-senligi/

Concrete wall at the Nusaybin Qamishli border. Photo: https://www.timeturk.com/suriye-sinir-duvari-tamam-iran-ise-bitmek-uzere/haber-911462

A Border City Without Borders is part of Urgent Pedagogies Issue#7: Entangled Topographies

is an urban planner; completed her thesis Spaces of Commons of Dispossessed Women: Women’s Laundry House of Benusen Neighborhood/ Diyarbakır and The Women’s Center/ The Square at the Fawwar Camp/West Bank (Palestine) under the Supervisor of Assoc. Prof. Dr. Pelin Tan (Mardin Artuklu University – Architecture Faculty). Yildiz’s research trajectory is about ecological feminist approaches on architecture, urbanism and spatial practices. Between 2013 and 2017, she worked at the Urban Planning Department of Diyarbakir Metropolitan Municipality and, among many other positions and commissions, she has been a delegate of Diyarbakır Branch of the Chamber of City Planners TMMOB (Union Of Chambers Of Turkish Engineers And Architects).

is an urban planner. Her research focuses on the geography of trash/waste, Z. Bauman and biopolitics, and the anthropocene. She completed her master degree in Politics and the Geography of Trash/Waste at the Master Program of Architecture at Mardin Artuklu University under the Supervisor of Assoc. Prof. Dr. Pelin Tan. She is a grants manager of International Medical Corps Turkey, an international humanitarian aid organisation for Refugees in Turkey that provides medical and outreach support to cross-border. She is responsible for conducting projects on the field, coordinating with local NGOs. She was the Project Coordinator of Mardin WasteWater Treatment Plant Project on behalf of Mardin Metropolitan Municipality for two years and she is a member of the Chamber of City Planner and Association of Human Rights in Diyarbakır.