Plotting from afar

Nishat Awan with Casper Lie, Maciej Moszant, Deniz Tichelaar and Kalina Yanakieva

CATEGORY

In the academic year 2020-21, I taught a graduation studio at the School of Architecture at TU Delft, as part of the Borders & Territories group under their multi-year programme “Emergent Border Conditions in Eurasia” [1].

It was the time of the coronavirus pandemic, and the usual mode of teaching through initial studio-based research followed by a two-week field trip was not possible. Within this context I suggested Gwadar, a place where I had been researching for the past few years, since it was clear that a European university such as TU Delft would not agree to a field trip to Pakistan, let alone a region within the country that is usually described in mainstream media as “the restive Balochistan province” [2]. Leaving aside arguments around the extractive nature of studio field trips and their rather superficial engagements with othered, and often exoticized places, I felt this was an opportunity to work with students in a more honest manner in relation to places they had not been to, had very little knowledge of, and yet were asked to respond to. This is not only a condition of architectural education, but also of contemporary architectural practice in its commercial guise. This approach can also be seen within a certain modality of architectural research, where there seems to be a compulsion to find sites (rather than places) that are more extreme, further out-of-bounds, and increasingly removed from the everyday experiences of those who choose to do this work. While much of my own research is based in Pakistan, where I am from, I am not Baloch. This question of how far you stray from the familiar and how other places are approached from a distance – which in my case is diasporic as well as ethnic – is something I have grappled with throughout my work [3]. So, these are not glib critiques but active concerns.

I brought to the studio, which was a small group of just four students, my research archive of images, videos, texts, and experiences, as well as contacts with people in Gwadar. The students supplemented this with their own research, mostly carried out on the web, scouring YouTube in particular, but also news articles, blogs and other online resources. In addition, the satellite images and mapping platforms ubiquitous to architectural and urban research were utilised to piece together an image of a place so deeply unfamiliar to this set of students from diverse European backgrounds. The wider Border Conditions graduation studio was studying Almaty, Kazakhstan; Beirut, Lebanon; Kashgar, China; Mashhad, Iran; and Yekaterinburg, Russia – cities equally unknown to the students, and in some cases also the tutors. The overarching brief of our design studios was to investigate the “array of spatial transformations, where different regimes of spatial planning, (inter-)continental infrastructural projects, political (dis-)agreements, border tensions, global capitalism, extra-state utopias and the like, are re-formatting the contemporary territorial and urban landscapes.” [4] This was to be done through a practice of mapping that explored and attempted to represent the above mentioned conditions.

The studio’s approach to mapping was heavily indebted to James Corner, particularly his book Taking Measures Across the American Landscape [5]. The mappings showcased in the book, and commented on by both Corner and Denis Cosgrove, aimed at producing novel interpretations of landscapes that merged the quantitative and the qualitative. The quantitative aspects were addressed through a critical understanding of how measuring itself produced territory, while the qualitative was encapsulated in a collaging approach that mixed photographs, maps and diagrams, in order to produce a commentary on the relationship between landscape and culture. While there is much potential in such an approach, the deeply depoliticised point-of-view meant that the authors failed to recognise the dynamics of, to state the most obvious examples, settler colonialism, slavery and the highly unequal labour conditions embedded within the landscapes that were so beautifully rendered. It was almost as if there was a failure to understand the co-constitutive relationship between measure and value [6]. Corner stated that the National Land Survey of the USA was “less about dominion and possession than it was about democratic and legal sale of land and its subsequent settlement.” [7] As Paige Raibmon points out in a review of the book, such a conclusion can only be reached through a politics steeped in white privilege [8]. Corner could have learned much from Sylvia Wynter’s 1971 article, ‘Novel and History, Plot and Plantation’, where she writes: “the planters gave the slaves plots of land on which to grow food to feed themselves in order to maximise profits. We suggest that this plot system, was, like the novel form in literature terms, the focus of resistance to the market system and market values.” [9] For Wynter the novel as a form of cultural production was deeply entwined with the plot as a landscape form that produced and supported the possibility of resistance through a folk culture that revolved around the communal life of the plots. The relationship between slavery, plantation economies, landscape and culture could not be clearer.

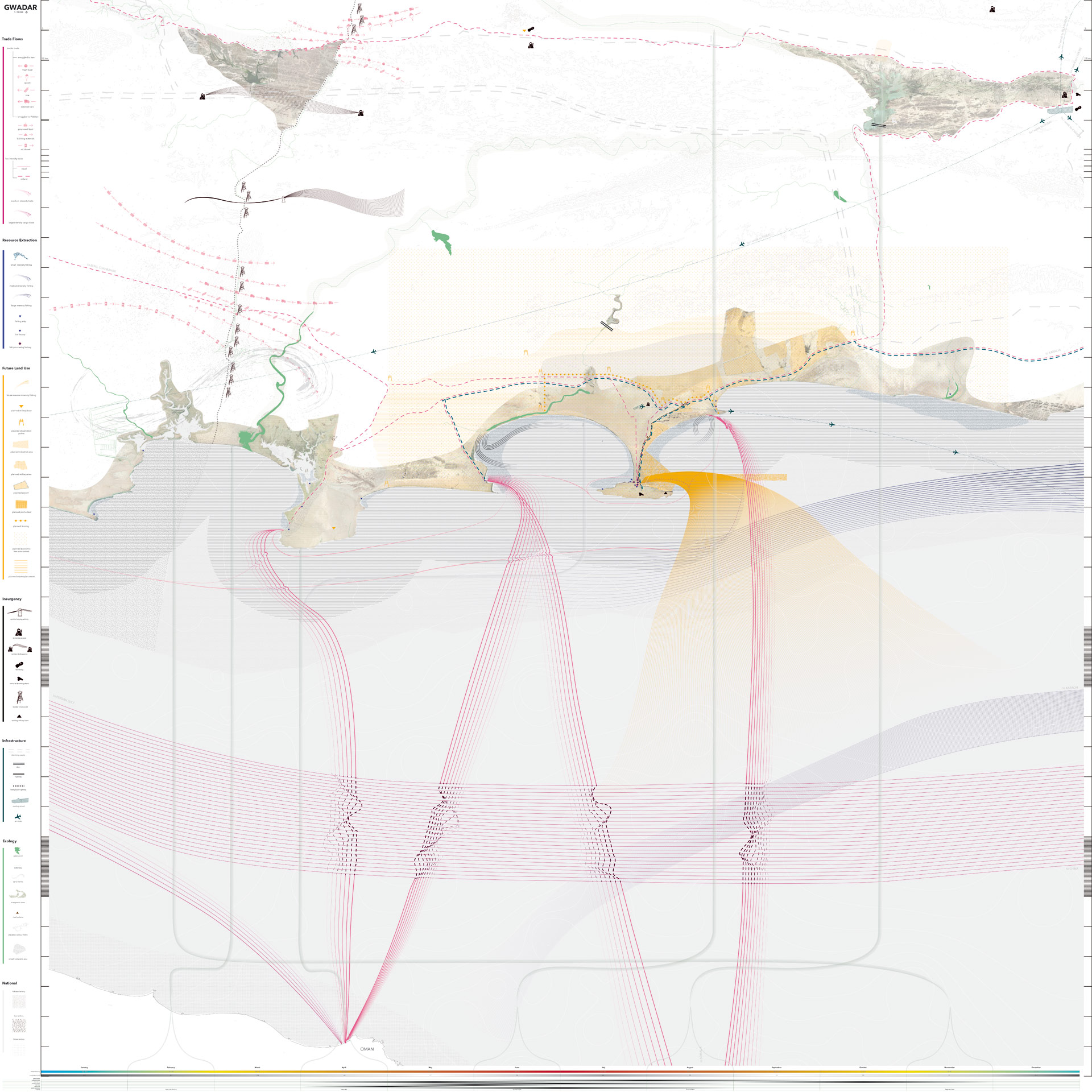

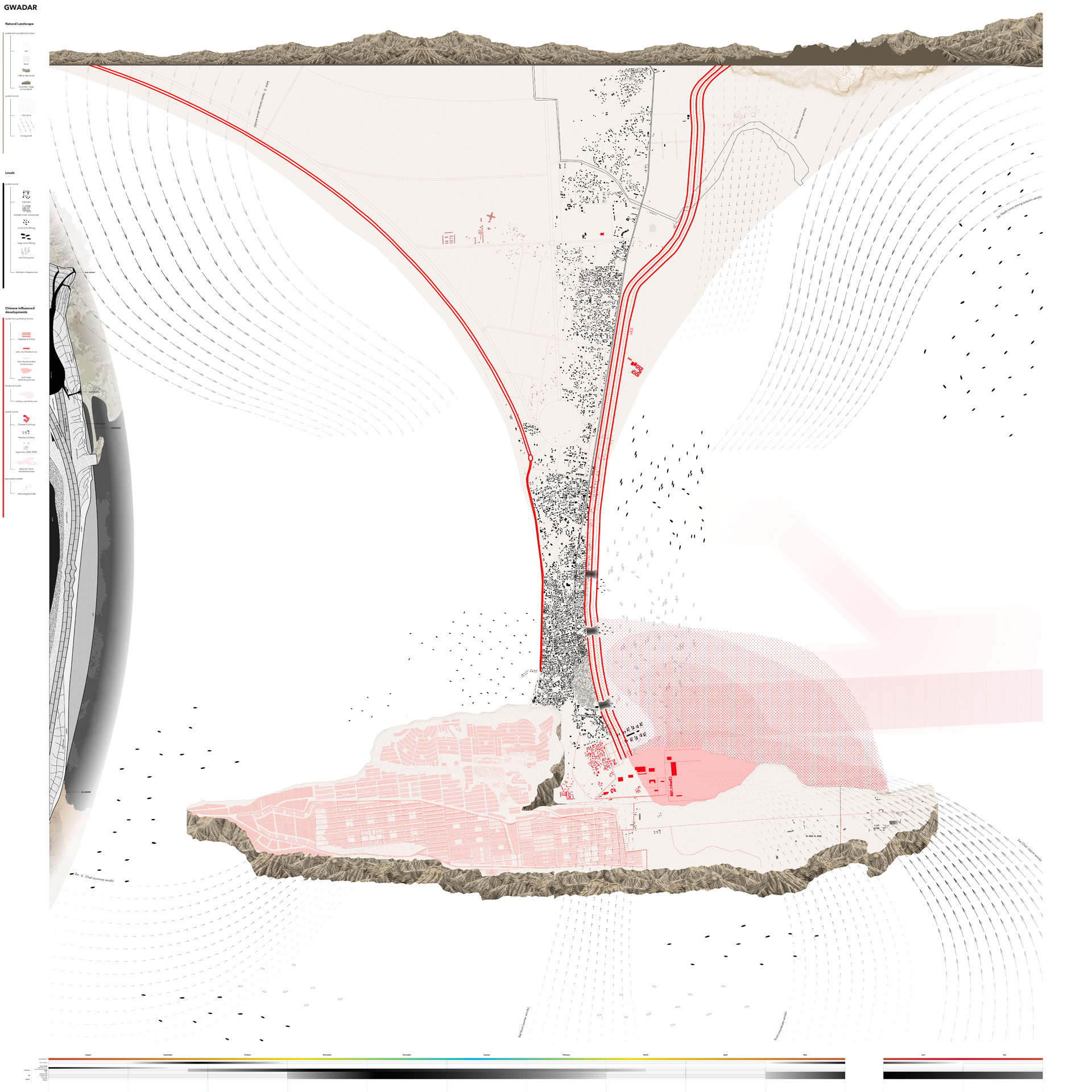

With Corner’s approach being such a strong reference for the wider studio, I was left with a dilemma – how to instil in the students the relationship between measure and landscape (or territory) without losing the all-important aspect of what values such practices of measurement embodied. I am not sure I fully succeeded. The wider studio brief required two large scale maps (1.8 x 1.8m in size) to be produced, one nominally focusing on the formation of territory, and the other on the production of borders. While this distinction often felt arbitrary, the two maps are different in the way they approach the same situation. The territories map looks at wider regional dynamics, while the borders map shows how these relations affect the everyday life of people in Gwadar. They both still adopt a bird’s eye perspective that is steeped in a colonial representational politics, but we did aim to open up the complex, deeply unequal and politicised relationships that have produced Gwadar as a territory to be parcelled off and sold, and to be bordered off from its inhabitants. In making the maps we addressed the border as a geographical and territorial phenomenon, a technology of government and a device that produces its own communities. We focused on the relations and exchanges across the arbitrary, and still contested Goldsmid Line that separates Pakistan and Iran, around an hour’s drive from Gwadar, and that cuts across the Baloch community. We considered the orientation of Gwadar as an historic freeport and its connections across the Arabian Sea to the Gulf and north Africa, alongside its current status as the terminus point of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which is itself an important north-south link within the wider New Silk Roads project.

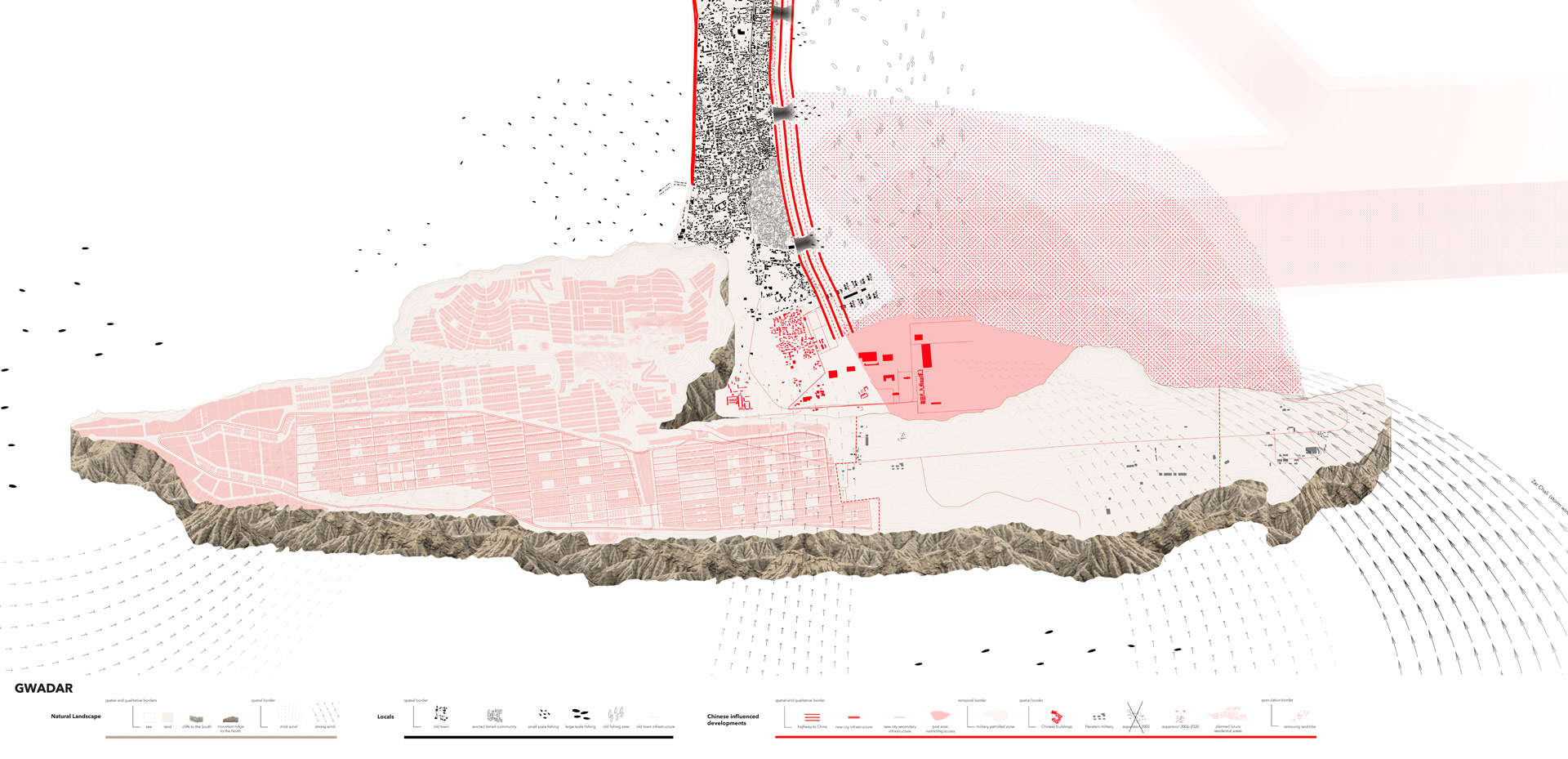

Entangled Gwadar (borders) (2020) Casper Lie, Kalina Yanakieva, Maciej Moszant, Deniz Tichelaar. Image: Borders & Territories, TU Delft.

The relationship between geology and community was also key to understanding Gwadar as territory; whether it was the string of mud volcanoes along the Makran coast that stretches across Pakistan and Iran and ties together an ethnic community across a colonial border, or the relationship between the fisherfolk’s embodied knowledge of the ebb and flow of the sea and the saint that protects them while out fishing. Both the land and seascape were considered as important actors in the current struggles over territory and resources. We considered how militarisation related to resource extraction producing new territorial formations and hardened borders in the service of geostrategic interests, but also how this inevitably intersected violently with local lives. The maps show these entanglements of infrastructural and extractive development that produce the increasingly bordered spaces of everyday life in Gwadar. The network of relations that supports informal trade and smuggling across the Pakistan-Iran border contrasts sharply with the planned development across the coast and the shrinking spaces of the fisherfolk. Conversely, the clandestine movements of Baloch militants take advantage of the rugged terrain and disrupt the inevitable logic of neo-colonial and militarised development. Together with the effects of seasonal and climatic changes these maps show the contested formation of borders and territories in Gwadar, and became the basis from which students produced speculative designs.

While the maps were able to show this highly oppressive system, what they failed to do was to imagine how such a system might have within it the seeds of resistance that could still produce other cultures and forms of living as Wynter’s account of the plot did. One student’s project, Maciej Moszant, did however begin to speculate upon other more emancipatory possibilities, and it is showcased here in this issue of Urgent Pedagogies [10].

Entangled Gwadar (territories) (2020) Maciej Moszant, Casper Lie, Kalina Yanakieva, Deniz Tichelaar. Image: Borders & Territories, TU Delft.

Entangled Gwadar (borders) (2020) Casper Lie, Kalina Yanakieva, Maciej Moszant, Deniz Tichelaar. Image: Borders & Territories, TU Delft.

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

Borders & Territories (B&T); https://www.borders-territories.space/education

2.

One of many examples: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/may/19/baloch-women-fear-crackdown-after-karachi-suicide-attack

3.

Nishat Awan. ‘Digital Narratives and Witnessing: The Ethics of Engaging with Places at a Distance.’ GeoHumanities 2, no. 2 (16 November 2016): 311–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2016.1234940.

4.

Borders & Territories Graduation Studio programme booklet (2020); https://www.borders-territories.space/education

5.

James Corner and Alex MacLean. Taking Measures Across the American Landscape. New edition. New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2000.

6.

For an overview see, Lisa Adkins and Celia Lury, eds. Measure and Value. Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

7.

James Corner & Alex MacLean. Taking Measures Across the American Landscape. New edition. New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2000, pp. 30-31.

8.

Paige Raibmon, Review of Taking Measures across the American Landscape by James Corner, Alex S. MacLean. Geographical Review, Vol. 87, No. 3 (Jul. 1997), pp. 427-429. https://www.jstor.org/stable/216047

9.

Sylvia Wynter. ‘Novel and History, Plot and Plantation’. Savacou, no. 5 (1971): 99.

10.

Maciej Moszant, ‘It starts with a wall’

is Professor of Architecture & Visual Culture at UCL Urban Laboratory. Her work is situated between art and architectural practice and her research explores the relationship between geopolitics and space through a focus on migration, displacement and borders. She is interested in modes of spatial representation, particularly in relation to the digital and the limits of witnessing as a form of ethical engagement with distant places. She is the author of Diasporic Agencies (Routledge, 2016) and co-author of Spatial Agency (Routledge, 2011).