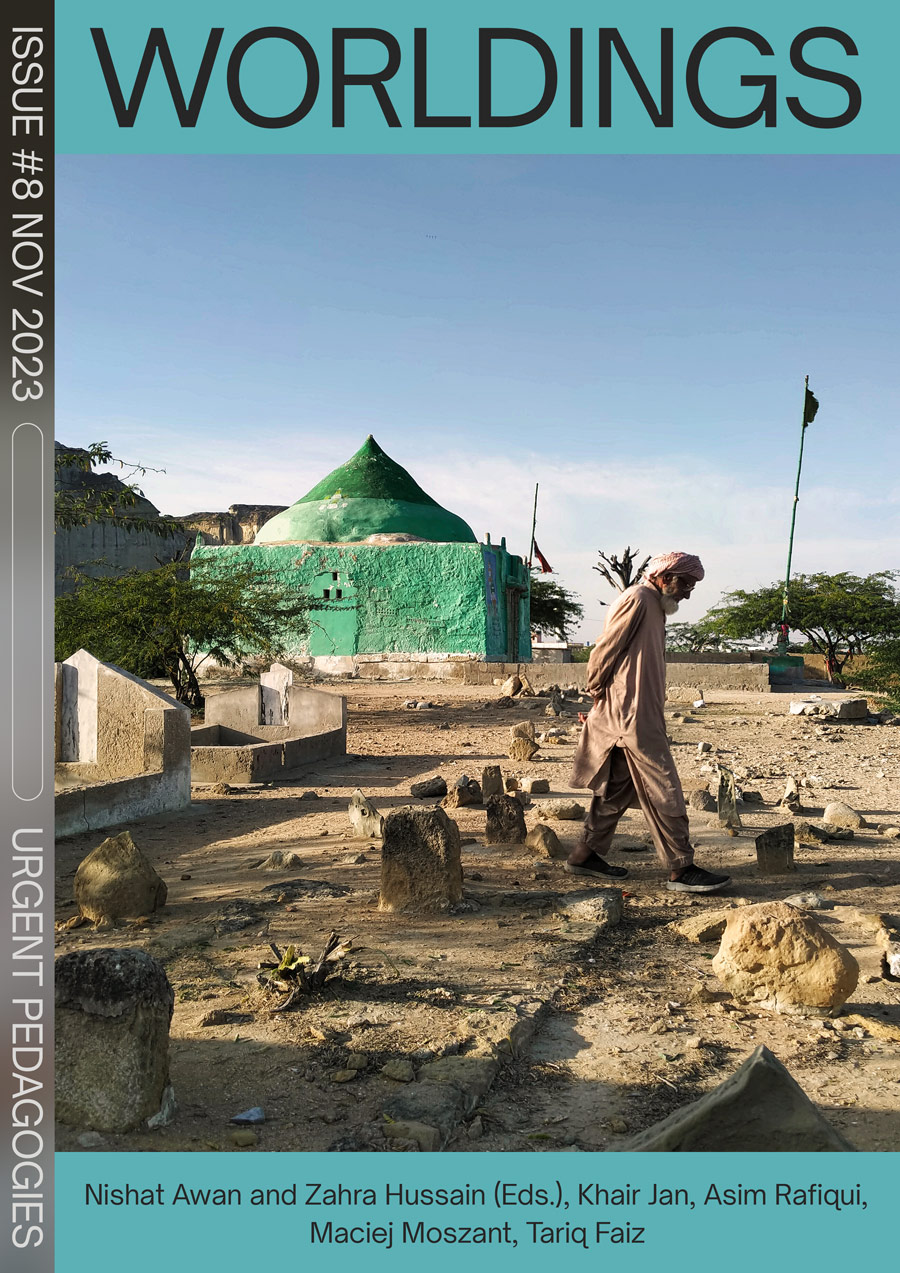

Issue #8

Worldings

Nishat Awan and Zahra Hussain (Eds.), Asim Rafiqui, Tariq Faiz, Khair Jan, Maciej Moszant

CATEGORY

Welcome to Issue #8: Worldings, guest edited by Nishat Awan and Zahra Hussain. Worldings presents research and engagement carried out in Gwadar, Pakistan, as part of the long-term project, Topological Atlas[1]. It considers the material effects of infrastructural development and its modes of worlding at different scales and through varied forms of pedagogical engagement.

Many aeons ago, when the world was full of wonders, when men sailed in ships to discover new lands and continents, at 25°12’16.7”N 62°20’47.9”E lay the secret of the ocean. A bubbling pond of mud slurry that is connected to the ocean deep beneath the visible layers of land; samandar ki naaf as people from olden times narrate, is the umbilical cord that provides the ocean with nourishment. It is believed that anything offered to the pond finds its way into the ocean. And the ocean is also where local inhabitants receive their nourishment and life through mahigeeri (fishing) and trade.

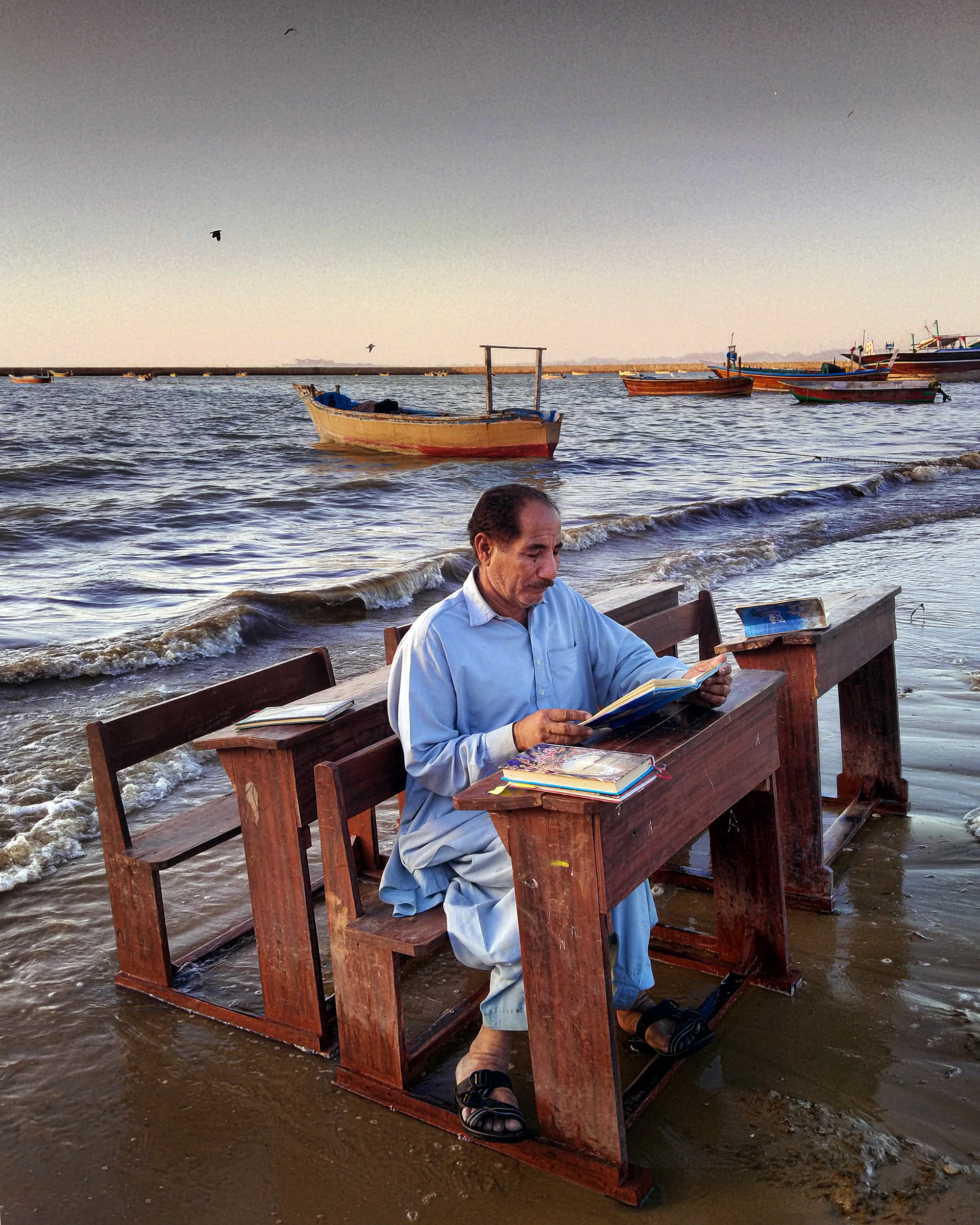

In this issue of Urgent Pedagogies, we explore the practices, forms and refrains through which worlds are produced, negotiated and made legible in Gwadar, an old trading town in current day Pakistan, with historic links across the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean. Here, everyday life revolves around fishing practices, locally known as mahigeeri. But another world has intruded upon Gwadar, a world where powerful actors imagine it as a node within a global infrastructural network. Gwadar is being developed as a strategically located port city on the southern end of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), connecting China to the warm waters of the Arabian Sea. The newly introduced Gwadar City and Port Masterplan has disrupted and displaced fisherfolk communities who have for decades lived and thrived in this land and in these waters.

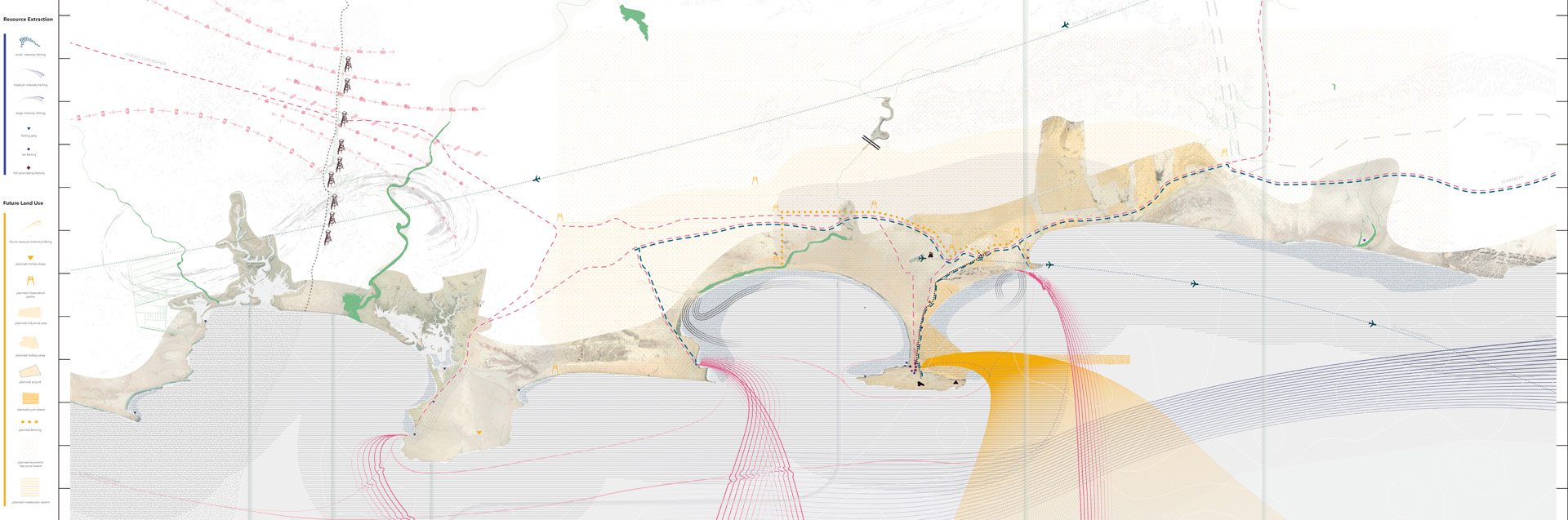

While we know that infrastructure is crucial to life, providing food, water, shelter and communication, certain forms of infrastructural development can curtail lives and worlds. We are interested in the capacity of infrastructure to organise and govern political, social, cultural and economic life, and in the ways that infrastructure affects environments and ecologies. In places like Gwadar, those who come with such development plans offer many promises and possibilities to marginalised communities. Here the entry into a world of amenities, of reliable electricity and internet, of roads that do not end abruptly in the sand, or the simple ability to study beyond high school in your own town, is not to be taken lightly. Yet, the destructive potential of a certain form of neoliberal, top-down development cannot be ignored. We explored this contradictory nature of infrastructural development and its modes of worlding at different levels, scales and forms of pedagogical engagement in Gwadar. This included a two-week workshop that gathered materials and conversations on site with the local community, students and others, a longer ethnographic engagement organised around teaching visual storytelling to local photographers, and a masters studio working remotely on a research archive and data available on maps and movement across the region. In presenting this collective work in Urgent Pedagogies, we aim to open up a discussion on the kinds of work it is possible to do in locations that are often considered far away, difficult to spend time in, or considering the context of the global Covid pandemic, simply not possible to travel to. We do this knowing that our own interventions also constitute forms of worlding.

Worlding in the way Donna Haraway and others describe it, opens up the enmeshment and entanglement of human and nonhuman in particular ways to make the world legible [2]. It is therefore a process of building and crafting relations that are ways of enacting and expressing, of effecting and being affected by certain entities whilst being disinterested in others. Certain forms of worlding fail to consider entities, ways of being, and forms of life that do not fit hegemonic accounts of reality, dismissing them as folkloric beliefs [3]. To move beyond such a perspective requires practices and tools of engagement that consider carefully, in Haraway’s words:

It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties. [4]

Worlding as an ethnographic endeavour questions our engagement with the world, asking how worlds are generated and related-with in certain contexts, places, events and environments. Worlding as generative and critical practice inspires this issue that explores multiple modes of engagement with peoples, contexts, places and events in Gwadar bringing to our attention what “matters” matter. For us, this has meant making room for other perspectives that are co-created, through imagery, descriptions, maps and stories, with local people, djinns, saintly presences, landscapes and their various articulations.

These can be described as experiments of engaging with place and people from near and afar; through different points-of-view, both spatial and social; through sustained conversations and observations; or through short lived interactions and exchanges. In how worlds are expressed, points-of-view become important not as modes of accessing these worlds, but as ways of making sense of them, through maps, images and visualisations. We understand that these are also forms of worlding that often do not produce neatly bound up accounts but are themselves complicit in generating frictions, negotiations and resistance. Certain entities that belong to one world can be completely absent from another. And so we keep in mind also Gayatri Spivak’s cautionary definition of worlding as the process that re-presents back to the colonised, their worlds understood through western and hegemonic forms of knowing [4]. We know that we must guard against the slippage between these two definitions and forms of worlding, which is for us the ongoing process of a decolonising pedagogy.

In this issue, we start with a field report by Nishat Awan and Zahra Hussain on the conflicting material imaginaries embedded within the landscape of Gwadar and the development plans being enacted for, and imposed upon, the place and its inhabitants. We then turn to Hussain’s cosmopolitical maps as attempts to render visible entities that do not feature in the hegemonic imaginary of Gwadar, introducing us to a world of djinns, fish, stars and the winds. Asim Rafiqui’s essay describes his experience teaching visual storytelling to students in Gwadar, and how the line between teacher and student blurred in projects that questioned the young men’s desires to project an imaginary of Gwadar. The next two contributions are the result of this engagement. Khair Jaan’s photographs and personal reflections on his neighbourhood of Dhooria question formal histories that do not account for local lives and experiences. We then zoom into a café in the same neighbourhood where Tariq Faiz’s photo essay is accompanied with a text by Rafiqui, immersing us into a living social world. This is followed by an article by Awan discussing her teaching practice from afar, where Gwadar is mapped and understood by architecture students who cannot go there but are informed of the place through a research archive. The issue ends with a speculative design project by Maciej Moszant, produced as part of the architectural studio, where a specific engagement with smuggling practices imagines an autonomous cross-border community. In all these accounts local people and their practices of worlding are engaged with, we consider how land and sea is navigated, how place and belonging is practised, and how hopes and desires emerge and simmer in an increasingly securitized and restricted landscape.

Contents

Conflicting Material Imaginaries

Nishat Awan and Zahra Hussain

Relating through Cosmopolitical maps

Zahra Hussain, Laajverd

Other Pedagogies

Asim Rafiqui

My Dhooria | میرا ڈوریا

Khair Jan Khairul

Kareemuk Hotel

Tariq Faiz and Asim Rafiqui

Plotting from afar

Nishat Awan with Casper Lie, Maciej Moszant, Deniz Tichelaar and Kalina Yanakieva

It all starts with a wall

Maciej Moszant

1.

This research has been carried out as part the Topological Atlas project funded by the (European Research Council) ERC under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no: 758529).

2.

Donna J. Haraway (2016) Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

3.

Isabelle Stengers (2005) ‘The cosmopolitical proposal’. In: Latour, B. & Weibel, P. (eds.) Making Things Public. MIT Press. pp. 994-1003; John Law (2011) ‘Collateral Realities’. In Fernando Domínguez Rubio and Patrick Baert (eds), The Politics of Knowledge, London: Routledge.pp 156-178.

4.

Donna J. Haraway (2016) Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, pp. 12.

5.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (1985) ‘The Rani of Sirmur: An Essay in Reading the Archives’ History and Theory, Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 247-272

is Professor of Architecture and Visual Culture at UCL Urban Laboratory. Her research and practice focus on the intersection of geopolitics and space, including questions related to diasporas, migration and border regimes.

is an Architect and Human Geographer based in Pakistan. Her research focuses on heritage and architecture particularly in the mountain landscapes of Northern Pakistan.

is a PhD candidate at TU Delft where he is conducting research into the seascape epistemologies of the mahigeer (fisherfolk) communities in Gwadar, Balochistan.

born and raised in Gwadar, is an architect by training and a photographer and filmmaker working on projects to help preserve and showcase the history and culture of Balochistan, especially Gwadar.

is an actor, producer, photographer, and a mahigeer (fisher) who was born and raised in Dhooria, Gwadar and comes from a long line of mahigeer who have claimed Gwadar as their home for at least six generations.

is an architect, graduated cum laude & with honours in 2021 from the architecture, urbanism and building sciences programme at TU Delft, Netherlands. He has also studied and practised as a designer in France and Poland, working on projects of different scales, from exhibitions, art installations to architecture and urban masterplans.