Kareemuk Hotel

Tariq Faiz and Asim Rafiqui

CATEGORY

This essay is a co-production. Despite spending considerable time at Kareemuk, a tea shop in Gwadar, I found it challenging to engage people in conversation. Suspicious of my intentions, a reaction any outsider would face, my presence was met with evasion and silence.

The essay is based on conversations my students–all from the city and regulars at Kareemuk–had with patrons at the café. Two were working on projects related to the social world of the café and spoke to people to understand its importance. I then talked to the students as part of my support for their project and also to understand what such places and spaces mean to Gwadar’s mahigeer (fisherfolk community). The students knew my research interests, carried my questions and queries into the café, and made them a part of their work. The essay incorporates ideas and insights generated during discussions, debates, planning, and thinking sessions between myself and the students, alongside my interviews with those few who were willing to talk to me about the significance of Kareemuk in their lives. All photographs belong to the students, Tariq Faiz and Rahim Sohrabi, and are used with their permission.

Asim Rafiqui

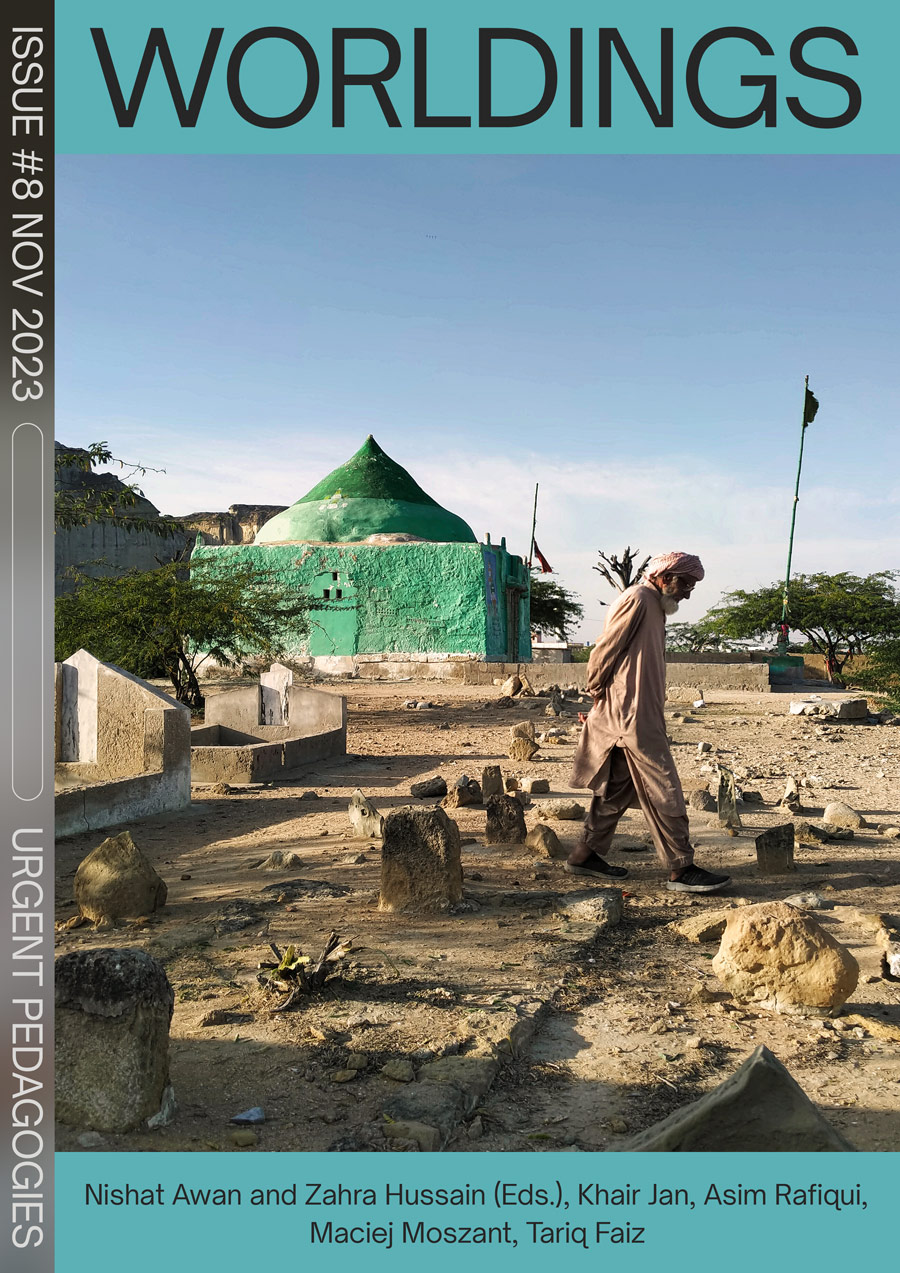

The neighbourhood looks like the aftermath of an aerial bombardment. The skeletal remains of two-storied buildings, almost all now little more than a pile of rubble and waste, stand leaning against each other, their former elegance and beauty reduced to collapsed walls, shattered windows, peeling paint, wayward wires, managed wood, and steel girders. Their walls, made from proud stone, now bear scars of years of neglect and weathering. Patches of paint cling to the walls and carelessly pasted advertising posters scream at passersby wherever the stucco hasn’t peeled off. Cracks snake up the walls, slowly but inevitably marking the time of the final demise. Wooden beams that once held up sturdy roofs lie rotting, their spines broken and shredded. Rain, debris, and garbage have seeped through roofless skeletons, leaving dark stains on the interiors. The alleys that meander gently through the neighbourhood, marking paths defined not by master planners but by the necessities and difficulties of the landscape and human desires, are riddled with deep craters, potholes, and rocks. Utility poles lie leaning and useless and look like arrows sunk in the blighted dirt, cast at the town by giants in the sky. An eerie quiet surrounds the area, so much so that one can hear the dust meet the dirt. People walk silently along these alleys, lowering their voices as if in a cemetery as they make their way between the long shadows cast by these crippled stone skeletons that stand as witnesses to times gone by. Those who peer into the remains of a building through the wound-like crevices in walls can glimpse at abandoned personal belongings, furniture, and other household items scattered among the ruins. These once were the foundations of someone’s home, but today, they are of interest only to the many drug addicts who roam the alleys searching for items to sell to salvage yards. Blackened, charred walls and the smell of burning wood testify to the presence of men cooking heroin.

Most who come here – the old Shahi Bazaar area – do so only to walk towards the Kareemuk Hotel, a small tea shop that sits deep in the heart of this post-apocalyptic landscape and remains the centre of social life for the mahigeer of Gwadar. The neglect, violence, and displacement that have made the neighbourhood a ghost town seem not to have affected this café and the many who come and congregate here. The stream of clients starts early, shortly after the muezzin calls for Fajr prayers, his voice carried across the homes with the help of crackling and popping loudspeakers that have seen better days. Among the first to arrive is Imam Buksh Musa, who has been delivering tea water for over 23 years, a job he inherited from his father Musa Gadhay Gari Wala (Musa, the Donkey Cart Owner), when he inherited his father’s donkey cart. In the weakening darkness of twilight, the buildings bathed in a livor mortis blue, Imam Buksh’s lithe figure, always in a poorly fitting, stain-laden shalwar-kameez that drapes around his thin body like a shroud, works quickly and with a practised economy of effort as the bussers sit smoking cigarettes and watch him unload the barrels of fresh water for the morning tea. Soon, the others will arrive: those preparing to leave for the sea, those returning from a night of hunting, those who are unable to leave because of a lack of money, petrol, nets, or crew, and especially those mahigeer who have lost their livelihood because of bankruptcy, lack of means, capsized boats or age. And the errand boys, with their metal flasks or stacks of clear plastic bags, to take back home. One can map the flow of tea from the café to the dozens of homes and businesses and understand how chai is never just a drink but a catalyst of relations.

A cacophony of clattering dishes and cups, murmured conversations, and the ominous hissing sound of full-power gas burners fills the air as you enter. Men sit about, undeterred by the chaos and disarray, deep in discussion, debate, argument, or learning. Some do not come: the recently arrived, city-educated engineers, drawn to the city because of the seaport bureaucracy; the Pathans from the North who remain recent arrivals and are seen as “outsiders,” the middle-class elite who prefer to have their tea at more upscale places in the city, and political and bureaucratic personalities uncomfortable with the bold and outspoken nature of the mahigeer. No signs, barricades, or bouncers stop people from entering, but there are social, cultural, and political fences that everyone seems to be aware of. The blocks of decaying buildings and twisting alleys that lead up to Kareemuk also discourage those unfamiliar with the town from entering the area. Many visitors to Gwadar never cross into this area, preferring to turn back at the edge of the busy marketplace around it.

Photo: Tariq Faiz and Rahim Sohrabi

Many others arrive too; at any given time, local politicians, administrators, bureaucrats, business people, vagrants, day labourers, shopkeepers, and neighbours can all be seen sitting on the small wooden benches, delicately balancing their glass cups of hot tea on wooden tables, their surfaces worn by years of use and exposure, leaving a landscape of deep ridges and depressions over which teacups wobble and teeter unable to find a resting place and requiring the constant attention of the drinker. Their surfaces are sticky and littered with crumbs, remnants of long-forgotten meals. Piles of unwashed cups, their contents encrusted and unidentifiable, languish in precarious stacks along the rear wall. A busboy is responsible for cleaning these when water is available. The air inside is a heady mix of fresh tea, cooked milk, stale sweat, and the mustiness of neglect. If you pay attention, you can also smell the sea – seaweeds, salt sweat, fish skin, blood – carried into the café by the mahigeer. The walls and ceilings are stained with years of accumulated grime and soot and decorated with outdated calendars, advertising posters, a wall clock that surprisingly keeps good time, and photos of the owner. Electric wiring snakes across the walls, finding its way to the low-wattage bulbs dangling precariously from their ceiling sockets, threatening to plunge the room into darkness. Tables, benches, cooking pots, cleaning utensils, buckets, water containers, wastebaskets, various burners, and gas canisters are scattered haphazardly throughout the cramped interior. Random items like crumpled newspapers, broken utensils, and even a solitary shoe seemed to have found their final resting place amidst the chaos.

Photo: Tariq Faiz and Rahim Sohrabi

Patrons often sit here for hours, nursing their tea and pieces of stale cake, knowing they are unlikely to be bothered in their reveries and conversations. Saleem Rasheed, suffering from severe mental health issues, is a regular. Once a courtroom clerk studying for his law degree, he wanders the streets of Gwadar and haunts the tables at the café at odd hours of the day. Like many other men with mental illness, he is a common sight at the tea shop and a part of the background noise and commotion that defines its atmosphere. Everyone knows them, makes space for them, and often buys them their cups of tea. Saleem’s vigil at Kareemuk has lasted well over two decades. Nakhuda Daud Kareem has been coming here since he was a child and can be seen sitting in the same corner of the café as he always had, holding court with friends and acquaintances. He has diabetes and cannot drink Kareemuk’s sugar-laden brew, so he brings his thermos of Suleimani (without milk) tea that his wife makes to drink at the café. Asif, the senior busboy, reheats it for him each morning and throughout the day so that he may enjoy it as he prefers. He never pays. As he sits enjoying the atmosphere, Asif, Shahbaan, and Kaka, the three full-time bussers, rush between the tables, dodging extended legs, flaying arms, stray cats, sleeping dogs, and even the occasional intrusive goat to deliver piping hot tea to the patrons.

Photo: Tariq Faiz and Rahim Sohrabi

Kareemuk’s is a mahigeer’s cafe, a place of rest and refuge, and an extension of their home. They can be seen sitting in their daily finest, celebrating the day’s catch, sharing tales of their hunt, and advising others where to hunt that day. Younger mahigeer come here to seek advice and guidance from the more experienced nakhudas (boat captains) and to understand the now fading yet still valued skills of reading the constellations and the sea to determine where a successful catch may be found. GPS units in hand, they sit at tables asking the older men how to read the stars and judge where certain fish will be seen that day. On any given day or hour, the men here talk about the sea, its moods, and its refusals. Notes are exchanged, advice given, warnings heard, jokes shared, disappointments soothed, loans arranged, repayments made, and negotiations finalised across from unstable tables and within the rising steam of fresh cups of tea. Others sit and gamble, play boardgames, surf the internet on their phones, share gossip with friends, tell of the news of the hunt, complain about the leaders of the city, province, and country, critique the military, abuse the intelligence services, laugh at the nature of national politics, share market prices of fish, and lament how corruption has undermined their lives. Inexplicably, one can say things at Kareemuk and express dissent and critique in ways unthinkable elsewhere in the city. Throughout the day, men head towards the café like camel trains towards an oasis. In the desolation of the neighbourhood, the muffled sound of conversations and laughter floats over the ruined and abandoned homes as if ghosts were at play inside the buildings’ dark, dust-filled rooms. The stranger is pulled towards the café, if only out of curiosity, to discover the source of the commotion. Locals can recognise the voices of friends even before they have turned the corner, their faces brightening at the prospect of the meeting to come.They also know that even when there are strike actions and protests, when almost all other businesses, including Kareemuk, shutter their front doors as an act of solidarity, you can enter the café from the rear terrace where a door is left discreetly ajar, and tea continues to be served inside.

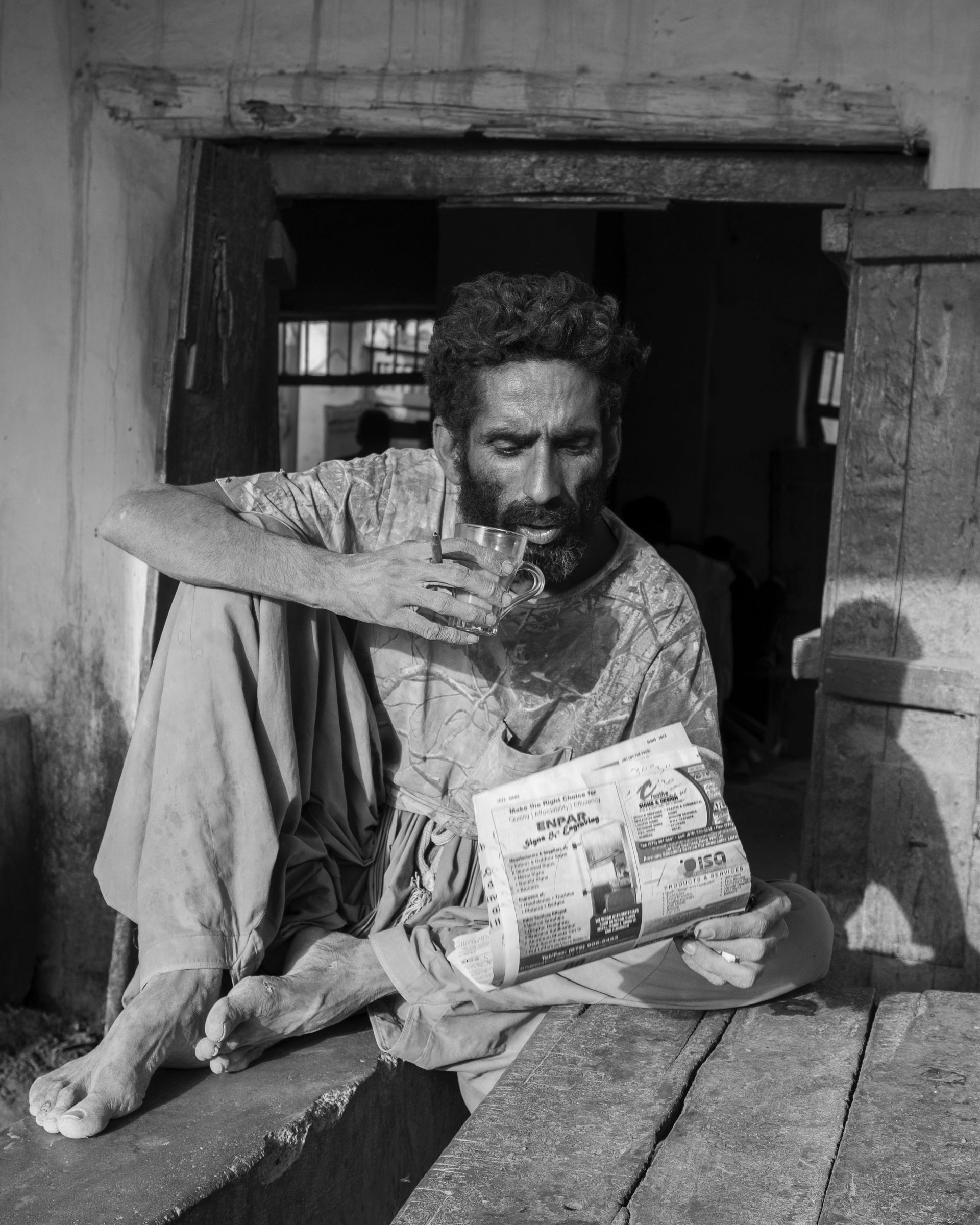

Photo: Tariq Faiz and Rahim Sohrabi

At the rear is a terrace, a cement structure with a metal roof that once faced out to the open sea but now resembles the interior of a prison block hemmed in by the chain-link fence and armed soldiers that “protect” the recently constructed expressway that connects the seaport to the warehouses some kilometres away. Men still come here, spilling out onto the ramshackle and run-down buildings surrounding the café, sitting on their haunches on the remains of people’s homes, quietly sipping away at their tea while looking out towards the sea. In the early morning hours, many come here to listen to an elder reading the local and national papers since only a few can read. Every day, its dark, cool interior is packed with men sitting with friends or alone, sipping away at their hot cups of tea, regardless of the time of day, the time of year, the mood of the seasons, or the goings-on in the rest of the city.

There were once other hotels here–the famous Lallu’s Cafe, Zeenat Hotel, and Maroog’s, that were equally popular with the mahigeer of this neighbourhood. They collapsed because of the same forces that have reduced this area to its current state of desolation and barrenness. Zeenat was particularly popular because of its musical evenings and performances, which were a significant draw. As the juggernaut of large-scale infrastructure work has overrun the community, the local mahigeer population has lost access to the sea. These waters that are this community’s lifeblood are locked behind steel fences, roadways, armed soldiers, and an electronic surveillance regime. As the battle for land and property grew and led to riots, people fled, and the hotels and other businesses in the area faded away. Yet, the Kareemuk Hotel inexplicably remains. The Zeenat had better music, Lallu’s had a better terrace overlooking the Demi Zirr Bay, and Maroog’s was more conveniently located. So why has only Kareemuk survived?

Ghafoor, the gruff and reclusive proprietor, says it is because he has run an honest business. He sits on a creaking rattan chair so low that only his eyes can peer over the cashier’s counter from where he scans the horizon of the world that is his café. Having lost his wife recently, he has become even quieter and more removed from things and people. But he is here every day, just as he has been since his twelfth year of birth when the then-owner enticed him to leave his previous job at a different café and join him at Kareemuk. A man of few words and an iron will, he sits quietly behind the counter, watching everything without looking as if he is. Ghafoor started here as an errand boy. The owner, Kareemuk, was a father figure and raised Ghafoor as his own. His portrait occupies a place of honour above the cashier’s counter. Later, he gave the business to Ghafoor and his friend Wahid Buksh. That was forty-five years ago—Ghafoor’s entire life. And yet, he, too, isn’t sure why Kareemuk still thrives among all this desolation. If you have to ask about it, he eventually mutters, you are not from here; you will never understand if you are not from here.

There may be no definitive answer. There may be as many answers as there are patrons, each finding his reason, compulsion and routine to arrive here. But there is one thing that even an outsider who spends some time at the café realises: Kareemuk is a living archive of a way of life that is becoming increasingly impossible to experience elsewhere in the city. As the mahigeer’s world is pushed back by an encroaching state, they are forced to seek refuge in a place such as this café. Kareemuk is a ruin where history, culture, biography, and experience come together under its soot and dirt-stained ceilings. Here, the men can retell the stories written out of history books, preserve the memory of those who shaped their lives, live the values otherwise considered “backward” and “unmodern,” share the oceanic wisdom otherwise regarded as irrelevant, and create a present otherwise unmarked by the forces and figures driving the city toward its future. Sitting within the ruins of this neighbourhood, the men reconnect with their memories and reaffirm their values and desires. This is not nostalgia but a utopian form of remembering and valuing–the ocean, the relations, the shore, the games, the friends, the political struggles, the oceanic knowledge, and wisdom–in the face of a world that is looking elsewhere. It is not a lament or a remembrance of a world the mahigeer know is being left behind and one that will not be sustained, but a recreation each day of a world that still matters and is their own. For the mahigeer, the future has been foreclosed, and the cycles of time have been interrupted. What lies ahead omits them. But here, in Kareemuk, you can recover it without explaining why.

“Every image of the past,” wrote Walter Benjamin, “that is not recognised by the present as one of its concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.” [1] But unlike Benjamin’s Angel of History, who looks back at the debris of history’s progress, the mahigeer live inside the wreckage of their own lives, and the realisation that all that can reconstitute, rejuvenate, and resurrect it is just within reach, and yet cannot be attained. But as long as Kareemuk remains in business, the foreclosed future can be held at bay. In this café, to be a mahigeer is to be held in esteem and honour. Here, the men can rediscover the continuity of a cultural life that has lasted for centuries, be at ease with familiar and known local norms, and bask in a sociality increasingly under threat elsewhere. Walter Benjamin argued that the storyteller’s art is dying because we no longer value “the ability to share experiences.” [2] But at this nondescript café, the art of storytelling, narrating histories, and rejuvenating genealogies remains alive. As you sit and listen to the men who gather here, you hear a living social world reclaiming itself without explaining itself.

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, Schocken Books, 1978:255.

2.

Walter Benjamin, “The Storyteller; Reflections on the Work of Nikolai Leskov,” The Storyteller Essays, New York Review of Books, 2019:96.

born and raised in Gwadar, is an architect by training and a photographer and filmmaker working on projects to help preserve and showcase the history and culture of Balochistan, especially Gwadar.

is a PhD candidate at TU Delft where he is conducting research into the seascape epistemologies of the mahigeer (fisherfolk) communities in Gwadar, Balochistan.