Relating through Cosmopolitical maps

Zahra Hussain, Laajverd

CATEGORY

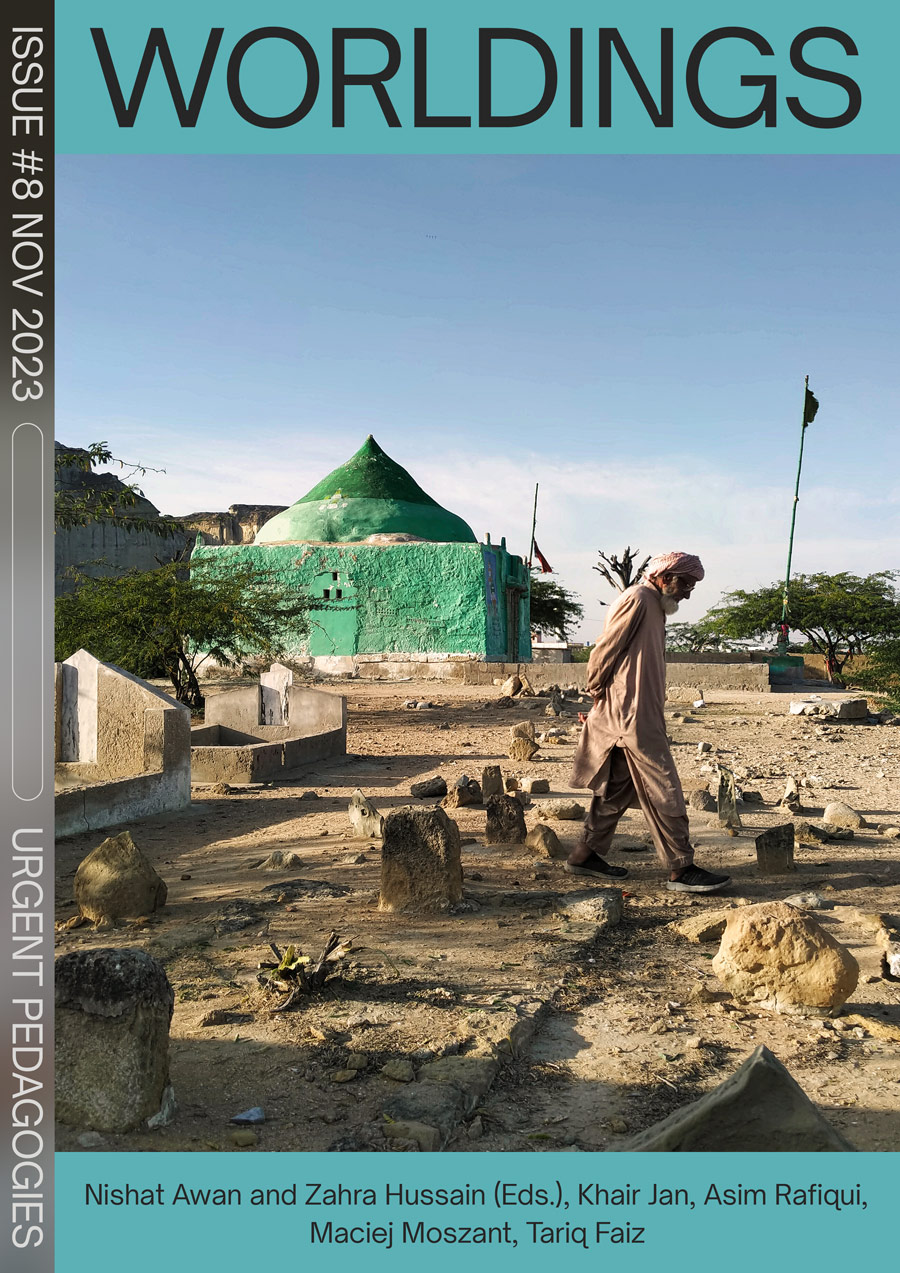

In planning interventions in the coastal town of Gwadar, fundamental questions arise regarding whose lives and ways of existence are deemed legitimate and worthy of shaping the future of these landscapes. Zahra Hussain discusses her practice of engaging with local communities in Gwadar through cosmopolitical maps; a process through which potentially conflicting worlds are rendered visible.

Our mysterious worlds, 2019. Drawing: Yumna Sadiq. Image: courtesy of Laajverd.

Indigenous fishing communities in the coastal areas of Pakistan are grappling with various challenges to their landscapes such as large infrastructural development, securitisation and climate change. In planning interventions, fundamental questions arise regarding whose lives and ways of existence are deemed legitimate and worthy of shaping the future of these landscapes. This essay delves into the methods employed to engage with the coastal community of Gwadar in southern Pakistan who are dealing with heightened securitization and restricted mobility, as well as limited access to the once-fertile sea due to the construction of a new port. Beyond simply mapping the physical landscape with the communities, this engagement required embracing a diverse array of perspectives. This meant forging connections with djinns and saints, conversing with wandering poets and madmen, and interpreting the traces and remnants left in the landscape through stories, folklore, objects, and practices that intricately shape the local environment. This engagement, at its core, transformed into a collaborative endeavor. It sought to understand how the coastal community of Gwadar connects with and upholds a sense of belonging to their changing landscape, especially in light of recent developments. It became a vital exploration into their relationship with a rapidly evolving environment.

Local and indigenous realities in marginalised areas that are mostly disconnected from an overarching imaginary of large-scale infrastructural development. These interventions are crafted through top-down state-led mechanisms for development that usually ignore the lives of local communities. Here, fragility is produced not just materially, but also immaterially through the conflicting imaginaries operating within the same landscape. This means that how these landscapes are cultivated and maintained by inhabitants/locals who experience it within their everyday lives significantly differs from what the state imagines these landscapes could become. In Gwadar, the infrastructural development consists of a six-lane highway connecting the national coastal highway to the deep water port. This intervention not only restricts access to the fertile side of the sea for local fishing communities, but has also dislocated their jetty. Moreover, ‘connectivity’, ‘prosperity’ and ‘mobility’ which this project claims to offer is not intended for the local communities exacerbating fragility and fragmentation within the landscape [1].

In the spring of 2019, I embarked on my first visit to the area in preparation for the Laajverd Visiting School. This ten-day program is an interdisciplinary and cross-curricular initiative, uniting experts, students, academics, and local communities. It combines insights from critical pedagogy and alternative practice bringing together experts, students, academics and local communities. It is organised to identify core themes and problem areas with local communities and explores creative ways of facilitating the development of local cultures, informal economies and creative industries [2]. The visiting school serves as a platform for discussion and knowledge exchange, hosting seminars, workshops, photo walks, tea sessions, and roundtable discussions. These activities enable various stakeholders to connect and engage with one another. In Gwadar, the visiting school was centered around the theme of ‘fragile scapes and fragmented lives’, aiming to understand how coastal communities were navigating the challenges posed by the development of the port.

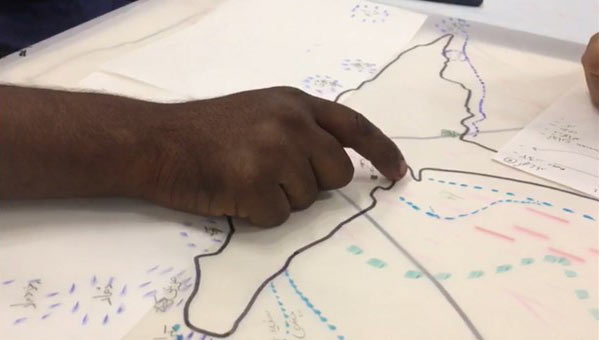

Upon arriving in Gwadar, the disjunction between our preconceived notions and the reality on the ground was stark. The glossy advertisements and news reports had painted a picture of Gwadar on the path to becoming a mini Dubai – a thriving center with towering glass buildings, bustling industry, and a well-connected infrastructure. However, what I encountered was a small, sparsely populated town with a vibrant coastal life. It became clear that the infrastructural development was forcefully erasing a culturally rich landscape primarily sustained by the fisherfolk, known locally as mahigeer. This vibrant coastal life didn’t seem to feature in any imaginary other than that of the local people. Driven by a desire to understand this dynamic cultural landscape, we collaborated with the local community through conversations, tea sessions, and mapping exercises. The goal was to create an alternative map of Gwadar, one that captured the sense of place and stories that were at risk of being forgotten and erased.

Oral stories have served as important assets in assessing the complex nature of heritage landscapes and used by travellers and explorers to ‘fill in blanks on their maps’ and extensively used by geographers to represent, de-code and analyse stories and their relations with space [3]. Within heritage mapping, an inclusive sense of ethics has been argued for where we recognise not only humans, but also non-human and more than human entities composing these heritage landscapes through their entangled relations [4]. Such entities often fail to feature on maps that follow western centric cartographic traditions. Attempts have been made to explore alternative forms of mapping that are collaborative and participatory in nature featuring stories and place-based experiences of communities to capture ‘depth of place’ [5]. Drawing inspiration from various alternative mapping practices, my colleagues and I embarked on a collaborative effort with local community members. Together, we aimed to craft visual maps that would encapsulate the multi-layered, and sometimes conflicting landscape of Gwadar. This endeavor entailed mapping not only the material elements but also what was cherished and recalled by the local people, particularly the mahigeer community. Through drawing, we discovered a newfound realm of exploration – one that delved into the invisible, the immaterial, and the imagined. In a landscape constantly undergoing transformation and erasure, drawing emerged as a vital medium. It allowed us to bring to life entities that only find existence through spoken word, memories, and dreams [6]. Through drawings, we wanted to explore the many worlds of Gwadar that were at risk of erasure. This meant employing a mapping strategy that draws in rather than leaves out, segregates or alienates; it attends to the multiple rather than assessing the landscape as a unitary existence. This, I call ‘cosmopolitical maps’, a mapping strategy inspired by Isabelle Stengers’ cosmopolitics for considering all entities and their worlds (relations, linkages through which they become present) without hierarchization, exclusions or simplifications [7]. Cosmopolitical mapping may be usefully employed in contexts and situations where an entity or landscape is at stake; of losing its legitimacy, life, sustenance in face of a dominant power that seeks to erase, undermine or destabilise it.

Cosmopolitical maps are an attempt to recognise human and non-human entities and their potentially other worlds. Such maps explore and draw upon the vitality of matter, non-human and more than human entities and their capacity to organise, transgress, dismantle and negotiate forms of ordering the world. Cosmopolitical mapping is a process through which these potentially conflicting orderings are rendered visible. Cosmopolitical maps don’t possess a definite structure or visual identity, neither do they attempt to foreclose the mapped entity towards a unilateral narration or visualisation, rather they seek to explore interrelations, interdependencies, synergies and disjunctures between multiple actors, entities and their worlds. By employing discursive and material techniques, this mapping process attempts to envision and compose common worlds by recognising entities and actors that are otherwise ignored, silenced, misrepresented in contemporary anthropocentric endeavours. In so doing, they seek to make visible alternative worlds, worlds that are at risk of erasure.

Cosmopolitical mapping, in my experience, is an immersive collaborative process. It involves actively listening to the narratives, delving into the nuances, and contemplating how these stories flow, transcend boundaries, evolve, and intertwine with other narratives, ultimately reflecting the essence of Gwadar’s landscape and its people. The objective of these visual maps was to articulate the diverse realities of Gwadar, shedding light on entities that often elude conventional mapping methods. We sought to bring forth the voices, memories, and experiences of local communities, incorporating not just human perspectives but also those of the more-than-human and spiritual elements that are inherently challenging to represent on maps. Through drawing, we aimed to delineate these elements, capturing their unique attributes and characteristics. Our cartographic approach was driven by the desire to acknowledge and illuminate entities that seldom find a place on conventional territorial, political, or tourism maps – in fact, they are often absent from visual maps altogether. Initially, we didn’t have a predetermined image of what these maps would look like. Instead, as stories were shared, I paid close attention to the specific ways in which entities were described and the intricate relationships that unfolded between various material and immaterial elements within the landscape.

Mapping the fertile sea. Photo: Zahra Hussain, 2019. Image: courtesy of LVS.

Following Stengers’ guidance on conducting inquiries which was discussed in the celebrated essay ‘ecology of practices’, I was careful that it is ‘through the middle’ and ‘with the surroundings’ that we must learn to work for ‘no theory gives you the power to disentangle something from its particular surroundings’ [8]. ‘Drawing in’ as a method of visualisation allowed the possibility of pulling in entities and their worlds in ways that maintain their characteristics, environments and modes of existence (in relation with the surroundings and other beings).

“In storms and high tides, Khizer is our guiding light, leading us safely back to shore. We pay our utmost respects to him every time we embark on a sea journey – he is our living saint,” shared a mahigeer, emphasizing how Khizer’s presence is a source of comfort and protection for them at sea. Some still honor his baithuk (where the saint once sat) before setting out, although, with the closure of the area due to the new port, these visits have become less frequent.

Recalling an incident from 2010, another mahigeer recounted a sighting near the Gwadar port. “In the evening, locals saw a fair-skinned man on horseback, clad in white attire. He held a staff in one hand, and as he cast a white object into the sea, the turbulent waters instantly calmed.”

For many mahigeer who have spent a significant portion of their lives at sea, Khwaja Khizer holds profound significance. They’ve witnessed phenomena and encountered beings that defy imagination, experiences beyond the grasp of those who reside on land as narrated by a mahigeer. The connection with Khwaja Khizer is akin to that of a river god or water spirit for those who navigate the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean [9].

In our stories, we also encountered another extraordinary being known as ‘Jatig’. Described as a formidable mythical creature taking human form, Jatig possesses the ability to traverse dimensions and transport souls. Legends speak of their tendency to fall in love with individuals, spiriting them away to alternate realms to live out their days.

One story about Jatig was narrated as below,

In a land steeped in enchantment, where witches wove their spells and djinns roamed free, there existed a tale of love that transcended realms. It was a story that unfolded in the ancient times when the Makran people sought new beginnings in the bustling city of Muscat. Among them was a Balochi woman, accompanied by her beloved daughter, seeking solace and a fresh start. Settling into their newfound life, they found joy and comfort in their Muscat abode. Yet, fate had a peculiar twist in store for them. One fateful day, the woman ventured into the heart of the bustling bazaar, unaware that the shop she entered was owned by a mysterious being known as a ‘jatig’. Her purpose was simple – to resize a cherished ring, oblivious to the hidden agenda of the enigmatic shopkeeper. Originally intended for her daughter, the ring had been too loose. Now, magically, it fit perfectly. However, as soon as the daughter adorned it, a shiver ran through her, and she departed this world. The mother, heartbroken and bewildered, sought solace in an unconventional decision. She beseeched that her daughter be laid to rest within their own dwelling, believing that in this way, she could remain close. Deeply troubled, she confided in an elderly sage, who considered the possibility of ‘jatig’ magic at play. To her astonishment, he offered a glimmer of hope – her daughter might not be truly lost, but rather dwelling in another realm. Acting on the sage’s counsel, she secured her abode as night fell, and began to chant sacred verses. Suddenly, the ground beneath her quaked, and before her eyes, her daughter stood, trembling yet alive. Overwhelmed with joy, the mother embraced her daughter, their bond unbreakable. They devised a plan – to depart Muscat in secret, leaving behind any trace of their return. It was imperative that the ‘jatig’ remained unaware of this miraculous reunion, for his wrath was not to be trifled with. In the quiet of the night, they embarked on a journey, carrying with them a tale of love, magic, and a bond that defied the boundaries of life and death.”

The recounted narrative sheds light on the enduring significance of the ‘Jatig’ in the cultural landscape of Gwadar. Even today, rituals aimed at beckoning back departed souls persist. Nevertheless, these practices are shrouded in secrecy, shielded from the prying eyes of both the general populace and visitors. As one mahigeer emphasized, this secrecy is upheld due to the belief that outsiders lack the comprehension of their spiritual knowledge. Embedded within these stories are references to locales that hold significance for Gwadar. They evoke reminiscences of a time when Muscat was easily accessible; Gwadar served as a liberated port, permitting unhindered movement and commerce with distant lands spanning the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean. These tales resonate with a palpable yearning for that bygone Gwadar. In parallel to the ethereal realm of rituals and recitations, the local inhabitants and mahigeer employ alternative forms of knowledge in their daily lives, anchored in the celestial choreography of stars. This indigenous wisdom allows them to discern critical aspects such as weather patterns, fishing seasons, tidal behavior, and enigmatic natural phenomena. It’s a testament to their intimate connection with the environment, where cosmic cues offer invaluable insights, further highlighting the profound connection between the people of Gwadar and the land and sea they inhabit.

For example, through the rising and falling of stars they come to know the weather conditions, fishing seasons, behaviour of tides and other mysterious events. As a mahigeer explained, the position of stars is mapped with reference to features on the land,

Waqa is a star that rises in the month of December (1st to 5th), look for it between the North-East on the top of the Sur mountain. It is an indication that winter is approaching. Naqa is the star that appears after fourteen days; the Naqa star rises from the same direction as Waqa. The sea is full of fish during this time. Some stars indicate the beginning of summer and some indicate storms. Then there are troubling stars – you see them together and there is trouble. The time before the last time we saw them together, the Russian invasion happened and then you saw how it troubled the whole region of Russia, Afghanistan and Pakistan. It was those stars, they give an indication and events follow – we do not what event will come, but we know it won’t be good.

These stories, beings and events were featured on the map we drew showing the interconnected nature of lives and landscapes in Gwadar; knowledge and stories passed on from ancestors and the processes through which beings cohabited the landscape of Gwadar. In our drawings, non-human beings and more-than-human entities manifested in two ways; they could be ascertained through their characteristics, and they were made visible within the recognizable landscape with waves against the night sky or through objects, such as Khwaja Khizer’s stick. The map is composed around the camel that ‘has a good memory and it can hold grudges against people who harm them’ (as narrated by local people), while a soul appears to be leaving the ground towards the sky; stars are positioned in the sky with dotted lines indicating their movement (rise and fall).

The process of creating cosmopolitical maps served as a means for the local community to envision, reminisce, and reconstruct their familiar landscape. These maps portrayed the characters and entities within it in a manner that was nuanced and not easily defined. The information we gathered hinted at a yearning for diverse interpretations of these stories. Unlike conventional participatory mapping that usually seeks community perspectives on a landscape, cosmopolitical mapping enabled us to acknowledge the myriad landscapes of Gwadar as they were lived, felt, and remembered by the members of the local community. The maps were meticulously crafted and layered, emphasizing the intricate relationships among the various entities and how they were perceived within the landscape.

The maps represented Gwadar’s landscape as multiple, non-linear and complex, entangled in the past and emergent in the present hence places and stories could not be coded into a single map offering a single view of the world. During the process of ‘drawing in’ other worlds, we were appreciative of the process of re-composition that allowed us to ‘build from utterly heterogeneous parts that will never make a whole, but at best a fragile, revisable, and diverse composite material’ [10]. Therefore, elements and entities re-appeared in different maps allowing the viewer to appreciate place-based belonging in the landscape of Gwadar. The collective and differentiated characterizations of an entity in multiple stories called for composing panels in multiple ways that assembled the landscape as remembered and imagined by the local inhabitants. ‘Drawing-in’ as a collaborative process with the local community members was crucial as it made entities visible in their particular environments and were featured alongside other beings. It gave visual reference points for communities to remember and for viewers to inquire about the local landscape of Gwadar which was partially known through stories and literary text. These maps functioned as archives, encompassing not only the heritage landscape but also the lifeworld of local communities. It is crucial to understand that these maps should not be viewed as final or limiting in the narratives they convey. Instead, they should be seen as dynamic, emergent and palpable compositions that open up avenues for envisioning an alternative Gwadar – and possible futures that are shaped and narrated by the local community.

This text has been adapted from original (long paper): ‘Drawing in’ other worlds: Addressing fragile heritage landscapes through cosmopolitical maps.

The research has been carried out as part the Topological Atlas project funded by the (European Research Council) ERC under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no: 758529).

1.

Awan, Nishat, and Zahra Hussain. 2020. ‘Conflicting Material Imaginaries’. E-Flux Architecture, no. New Silk Roads (January). https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/new-silk roads/312609/conflicting-material-imaginaries/.

2.

Hussain, Z. (2020). Encountering the cosmos; negotiating conflicting worlds through learning and engagement. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in the South, 4(2), 180-196.

3.

Caquard, Sébastien, and William Cartwright. 2014. ‘Narrative Cartography: From Mapping Stories to the Narrative of Maps and Mapping’. The Cartographic Journal 51 (2): 101–6. https://doi.org/10/f56r23.

4.

Catalani, Anna. 2017. Water & Heritage: Material, Conceptual and Spiritual Connections. Taylor & Francis.

5.

Nardi, Sarah De. 2014. ‘Senses of Place, Senses of the Past: Making Experiential Maps as Part of Community Heritage Fieldwork’. Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 1 (1): 5–22. https://doi.org/10/gfc5bj

6.

Antona, Laura. 2019. ‘Making Hidden Spaces Visible: Using Drawing as a Method to Illuminate New Geographies’. Area 51 (4): 697–705. https://doi.org/10/gfttfk.

7.

Stengers, Isabelle. 2005. ‘The cosmopolitical proposal’. In: Latour, B. & Weibel, P. (eds.) Making Things Public. MIT Press. pp. 994-1003.

8.

Stengers, Isabelle. 2005. ‘Introductory Notes on an Ecology of Practices’. Cultural Studies Review 11 (1): 183–196. https://doi.org/10/gdxwhp.

9.

Hussain, Hamid. 2007. Sufism and Bhakti Movement: Eternal Relevance. Manak Publications Private Limited.

10.

Latour, B. 2010. An Attempt at a “Compositionist Manifesto”’. New Literary History 41(3), 471-490. doi:10.1353/nlh.2010.a408295.

is an Architect and Human Geographer based in Pakistan. Her research focuses on heritage and architecture particularly in the mountain landscapes of Northern Pakistan. She leads the Academy for Democracy project that is a cross curricular and interdisciplinary program exploring forms of engagement with changing landscapes. She has written the book ‘Mountain Architecture Guidelines’ and drafted building bye-laws and codes for the protection of the local built environment in Kalash Valley, KPK in north western region of Pakistan. Currently, she is a visiting fellow at the International Institute of Asian Studies (IIAS) in the Netherlands where she is writing about ‘heritage cosmopolitics’ as a way of approaching contemporary mountainous Asia.

‘Drawing in’ other worlds: Addressing fragile heritage landscapes through cosmopolitical maps https://doi.org/10.1080/20518196.2021.1894765