Translating lifeworlds: curatorial practice and epistemic justice

Silvia Franceschini

CATEGORY

“The curatorial as a regime of the management of aesthetics between the institutional and the artistic field is where the idea of epistemic disobedience might be fostered.”

It seems the time has come when it has become urgent to put curatorial practice on new conceptual grounds that interrogate and challenge the ethics of production, representations and dissemination of knowledge. Understanding the institution and the exhibition as places where, both historically and in the present, cognition and aesthetics have partaken and enacted frontiers and borders across different epistemological registers[1], poses challenging questions to the activity of cultural workers in the European environment. How can we foster new institutional paradigms and new alliances that respond to increasingly diasporic public spheres? How to challenge the raciality that hierarchizes knowledge and ways of producing knowledge in the majority of our institutions? How, as Dipesh Chackrabarty asks, can a cultural worker operating in highly antagonistic neocolonial arenas of struggle, be someone able to translate diverse and enchanted ways of world-making[2], embracing translation as a labor of mutual affection, unsettling universal claims and authoritarian positions? In the following text I try to recompose the legacy of a certain critical thinking that might help to envision the practice of curating as responsibility towards others. I have directed my attention to the work of artists, designers, theorists and curators who have critically challenged the hegemony of dominant disciplinary systems through a process of “epistemic disobedience”, a refusal of oppressive epistemic structures in order to envision social life, knowledge and institutions differently. The curatorial process can be a space to pose enabling questions for dealing with a world driven towards cultural conflicts created by the failure to recognize the different ways of knowing and relating by which people across the globe run their lives and provide meaning to their existence.

The American Bengalese philosopher Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, drawing from Foucault’s theories of knowledge, defines “epistemic violence” as a means for building knowledge as a tool of power, together with the support and legitimization of dominance (Spivak 1988). The concept was further elaborated by the Argentinian semiotician Walter Mignolo in his well-known 2011 article “The Geopolitics of Sensing and Knowing,” where he speaks of “epistemic disobedience” as a strategy of civil disobedience within processes of construction of knowledge (Mignolo 2011). In the same article, Mignolo develops the idea of “border thinking,” an epistemic framework to describe theories that sit at the very borders (if not outside) of the colonial matrix of power. The epistemic question in connection to the history of colonialism was raised for the first time in 1990 by Aníbal Quijano’s formulation of the concept of “coloniality” as the perpetuation of colonial institutions, forms and structures that are necessary to sustain modernity in the peripheries.

For Walter Mignolo, Arturo Escobar, Aníbal Quijano, Enrique Dussel, and other intellectuals and scholars from the Latin American Modernity/Coloniality/Decoloniality group,[3] contestations over the exact sciences in the name of indigenous knowledge or alternative knowledge can be read as part of a broader challenge to the limitations of modernist thought, entangled as it is with capital. Decoloniality is a political and epistemic project that seeks to produce a radical and different knowledge, a “knowledge otherwise” (Mignolo 2000; Escobar 2007). The decolonial theorist de Sousa Santos speaks along these lines about an “epistemicide” that Europe committed in the colonies, and makes a plea for epistemic justice condemning the universalization of hegemonic knowledge. In his text “Beyond Abyssal Thinking” (2007) he proposes a type of knowledge that is against the homogenization and universalism of modern culture and in favor of plurality. An ecology of knowledges can only be based on the fact that all knowledge is always inter-knowledge, or knowledge based on the relational antagonism of ideas: “The ecology of knowledges is the principle of consistency underlying constellations of knowledges.”[4] According to de Sousa Santos, the transition toward a pluralism of knowledges will lead to the formulation of a counter-epistemology turnover that will challenge the idea of knowledge-as-regulation:

Knowledge-as-regulation knows through a trajectory that goes from ignorance, regarded as disorder, to knowledge, described as order, while knowledge-as-emancipation knows through a trajectory that leads from ignorance, conceived of as colonialism, to knowledge conceived as of solidarity. It is in the nature of the ecology of knowledges to establish itself through constant questioning and incomplete answers.[5]

The idea of “ecologies of knowledge” emerges in the context of a bigger research in Epistemologies of the South (2014), which the Portuguese scholar carried out in strict connection with social movements and emancipatory projects through the so-called Global South. The starting point of the book is the exhaustion of Northern and Western models of knowledge and the urge to look at forms of knowledge that must be brought into the conversation and that don’t take a scientific approach because they are rather born of struggle. The author claims that universities and other centers of knowledge production only teach the “knowledge of the winners,” while in order to draw a different narrative, that of the “losers,” it is necessary to see from the perspective of social groups that have systematically suffered discrimination, exploitation, oppression of capitalism, colonialism, and patriarchy. He promotes the transformation of discourses that challenge hegemonic epistemology through an “epistemological decolonization.” This implies reclaiming orality, different worldviews, art and culture, as well as so-called embodied theories which, according to the feminist cultural theorist Gloria Anzaldúa, speak not from the academy but from experience and the body (Anzaldúa 1987).

Mignolo and Tlostanova (2012) emphasize the importance of the body-politics of knowledge, and, following the transnational and transcultural logic of border thinking, suggest the necessity to unlearn what we have been taught and had consciously or unconsciously imposed on us by a Western imperial model of education, culture, and social environment. De Sousa Santos asserts that “Learning certain forms of knowledge may involve forgetting others and, in the last instance, becoming ignorant of them” (2007, 69). In his idea of ecologies of knowledge, ignorance and unlearning are two significant parts of the learning process. Learning and unlearning are often in connection: “learning” to “unlearn” each basic cultural assumption in order to “relearn” more freely. Spivak speaks about the necessity of “unlearning of one’s privileges” (Spivak 1990, 42) and prompts us to try “learning to learn from below,” which for her means being able to learn from subaltern positions (1988).

Finally, it is in the humanities and in the aesthetic regimes where, according to Spivak, the imagination is allowed to unfold in such a way that a different thinking is possible (Spivak 2012). The curatorial as a regime of the management of aesthetics between the institutional and the artistic field is where the idea of epistemic disobedience might be fostered. In her text “Memories of Underdevelopment”, art historian Julieta Gonzalez identified early instances of decolonial aesthetics and epistemic disobedience in the practice of artists and architects such as Lina Bo Bardi. Bo Bardi formulated a counter discourse to the rhetoric of developmentalism, which became a global ideology in those years, by exploring their structural affinities with the vocabularies of the popular, material poverty, and the conditions of cultural production in the Third World[6]. In her work as a curator, directing the Modern Art Museum of Bahia (1960), the architect Lina Bo Bardi aimed to bring together a project of modernity in the artistic, cultural, social and economic fields with the matrix of local popular culture, pioneering a proposal for a new museology based on “recycling, education, and the alliance between craft technics and industrial design.”[7] Bo Bardi commingled the commonly opposed realms of the museum and the practical worlds of production in a “museum-school,” a terrain in which craft and art would coexist, challenging the accepted superiority of the museum in relation to the school, and of art in relation to the utilitarian field. According to Julieta Gonzalez, Bo Bardi’s practice employed a strategy of epistemic disobedience in the way she challenged a modernity that, by inscribing into its canon the narratives of progress, perpetuates the colonial condition[8]. Her approach was in line with Paulo Freire’s discourse on popular education and took an early decolonial perspective. Bo Bardi´s 1969 exhibition “A mão do povo brasileiro”, which was realised at The São Paulo Museum of Art MASP incorporating objects from the entire country and cultural traditions, was re-enacted in 2016 to start a strategy of decolonization of the museum, in a program around the notion of “histories”, which dispel the idea of a single narrative by unfolding “histories from the margins”.

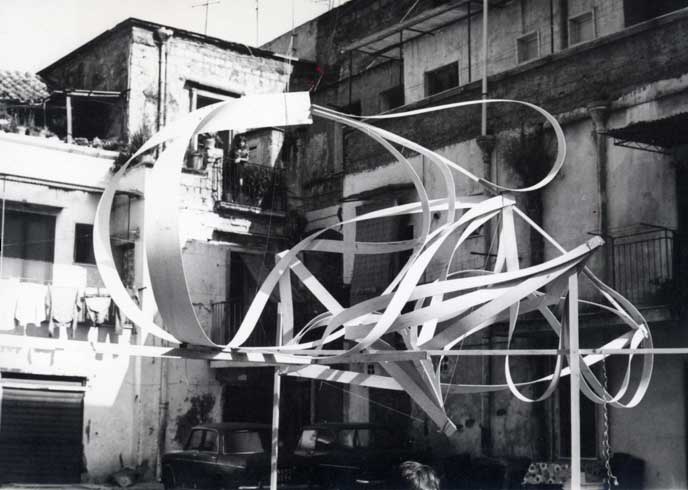

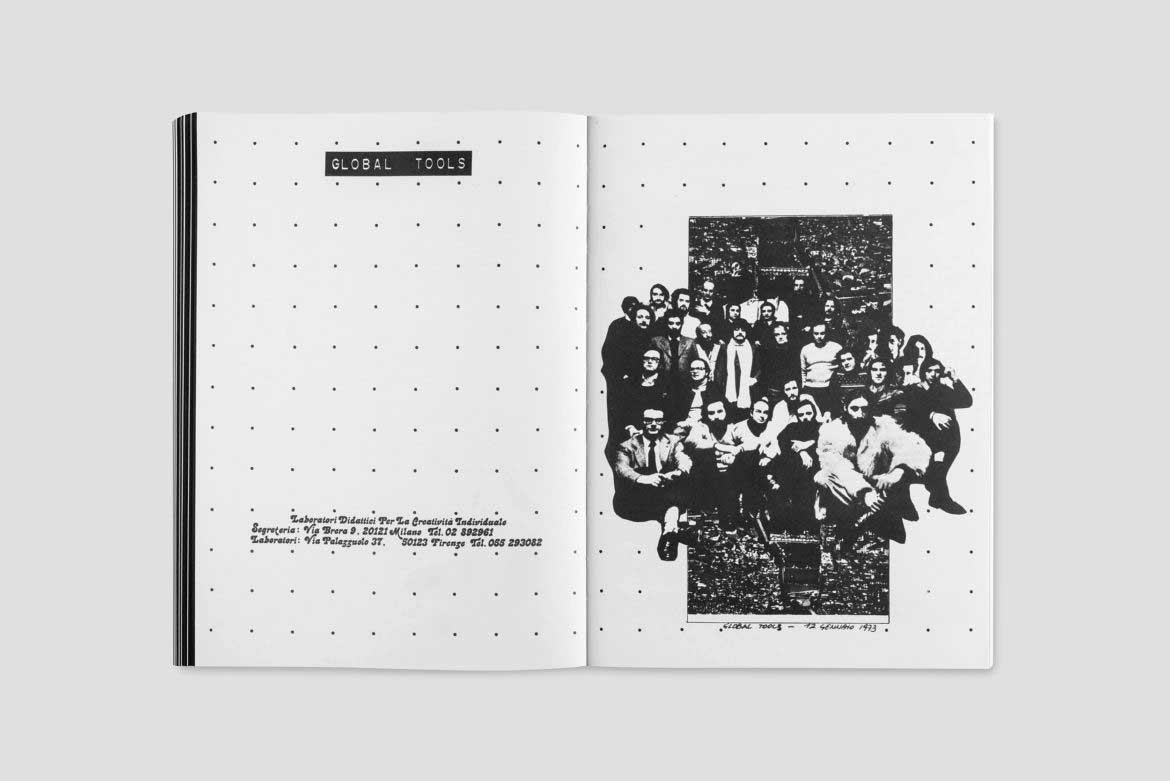

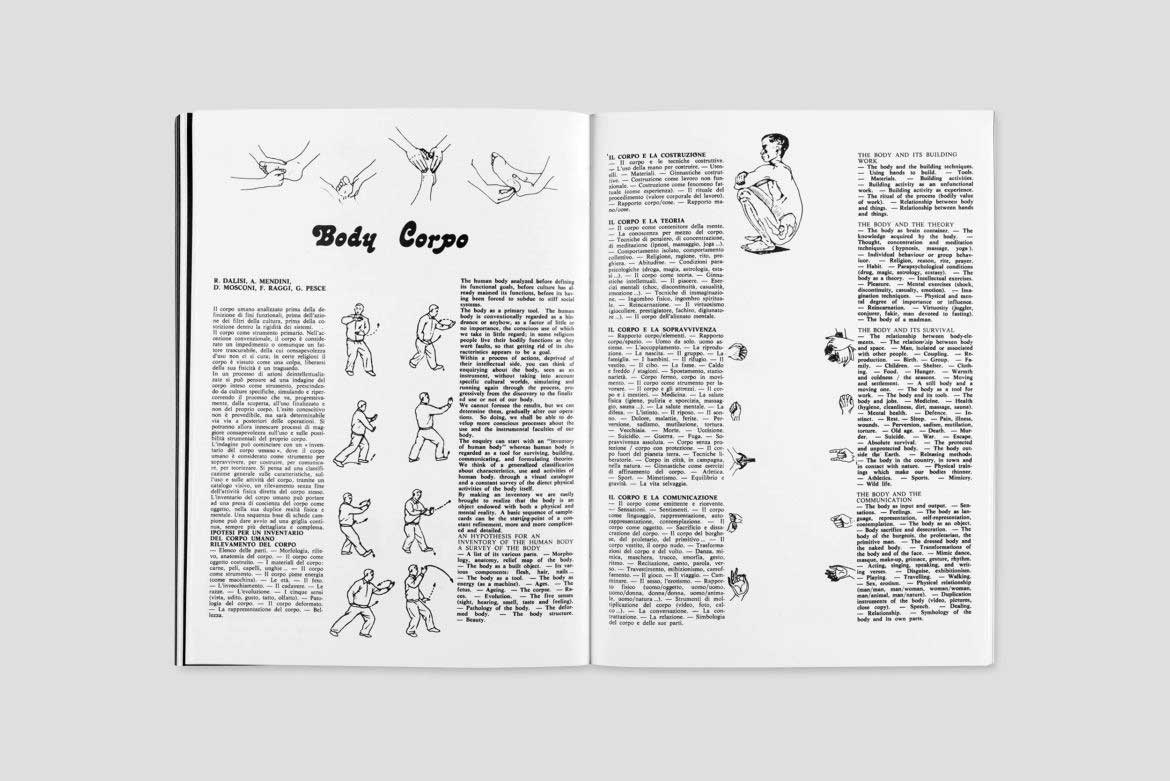

The premises of Bo Bardi were similar to the one of Global Tools, a movement and pedagogical experiment born in Italy from similar concerns over vernacular and material culture as a form of low culture that can tackle rationalism and modernity from below. The members of Global Tools shared with Bo Bardi the interest for Ivan Illych and Paulo Freire and their work on education, popular culture and on the limits of development. With workshops all over Italy, from the marble caves in Padua to the suburban districts of Naples, the idea was to use improvisation in construction, the body and performance as an instrument of learning, and an epistemic rebellion to the discipline of design and architecture and their implications with modern development. In the exhibition Global Tools. 1973-75 Towards an Ecology of Design[9], the curator Valerio Borgonuovo and I tried to assemble an open archive of this experience that finally never transformed into a real school, and put it at the service of the people to reimagine new pedagogical tools for the current era.

Raphaël Grisey & Bouba Touré, Sowing Somankidi Coura, a Generative Archive, exhibition view of Le Déracinement. On Diasporic Imaginations, Z33 House for Contemporary Art design and Architecture, Hasselt, 2021. Photo by Selma Gurbuz.

In his text, Provincializing Europe, first published in 2000, Chakrabarty calls for pluralization of the history of global modernity[10]. Writing subaltern history, that is, documenting resistance to oppression and exploitation, must be part of a larger effort to make the world more socially just. In more recent studies, the Indian scholar has also enriched the discussion with the current climate change debates which, he argues, upends long-standing ideas of history, modernity, and globalization[11]. How does this necessary change in paradigms of history writing apply, translate to institutional programming?

Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc, Walking Through the Arawak Horizon, for Wilson Harris exhibition view of Le Déracinement. On Diasporic Imaginations, Z33 House for Contemporary Art design and Architecture, Hasselt, 2021. Photo Selma Gurbuz.

The exhibition Le Deracinement. On Diasporic Imaginations, which I curated at Z33 House for Contemporary Art, Design and Architecture, was an exhibition connecting past and present struggles against the violence of uprooting. Departing from the collaborative work done by Pierre Bourdieu and Sayad on the violence of uprooting in Algeria during the war of Independence, the exhibition was deeply inspired by Sayad´s latest work on the formation of postcolonial European diasporas and the relation between coloniality and institutional racism[12]. Historically grounded in the role that migration had in the making of European modernity, the exhibition featured artworks that reimagine, disentangle and rewrite colonial and postcolonial histories of displacement. They documented the encounters that took place in diasporic settings and narrated the networks of solidarity that have emerged in between worlds, looking at forms of cultural inheritance that survive in the present. The exhibition foregrounded the radical challenges posed to the image of a self-contained Europe, by diasporic communities. Artists evoked fictions and imaginations, shifting our gaze from the comfort of solid grounds to one of restless seas and hybrid identities created over centuries, through trajectories that crisscrossed the Mediterranean and Atlantic. They questioned the language of integration, assimilation and inclusion that is assumed within national frameworks and disrupt exclusionary concepts of belonging.

The exhibition was part of a longer trajectory and program of exhibitions at Z33, exploring social histories that have shaped today’s global order[13]. The series of exhibitions invited artists and researchers to reflect on the effects of uneven globalization and to imagine equitable ways of world-making, bringing together works that examine the persistent continuities between colonial history and present forms of exploitation. The series of exhibitions traced the migrations of people, materials, and ideas drawing attention to international artistic alliances that forge new geographies of collaboration. The core of this idea was to put research between disciplinary fields and in dialogue with different constituencies at the center of institutional programming. How can artistic research help us to find alternative ways of living and cooperating? How can different constituencies enlarge the agencies of research among the larger civil society?

Pavel Althamer, The Draftsmen’s Tent of Ghosts, part of The School of Kyiv— Kyiv Biennial 2015. Courtesy The School of Kyiv— Kyiv Biennial 2015.

To make an institution accessible and a welcoming place for the community was the aim of the School of Kyiv, Kyiv Biennial 2015, where I took part as member of the curatorial team[14]. This was a newly constituted biennial organized with the Visual Culture Research Center in Kyiv, as an alternative to the state-run governmental biennial initiative. The School of Kyiv presented a new format of an art biennial that integrated exhibitions with sites of public reflection. Its program of classes was conceived as a place where artists, intellectuals, cultural workers, experts, and activists could meet with audiences to learn, reflect, and produce new works with the idea that education and art could become emancipatory tools for civil society. By means of an educational program that included not only lectures and classes but also performances, spontaneous gatherings, poetry, films, and many other modes of expression, The School of Kyiv attempted to give shape to new political subjectivities that emerged in Kyiv in a situation of social and political instability[15]. The cultural anthropologist Victor Turner defined the importance of learning from what he called “liminal moments”—events such as political or social revolutions that result in the collapse of order and significant social change. During liminal periods of all kinds, social hierarchies may be reversed or temporarily dissolved, continuity of tradition may become uncertain, and future outcomes once taken for granted may be thrown into doubt. The dissolution of order during liminality creates a fluid, malleable situation that enables new institutions, customs and epistemologies to become established. The goal of The School of Kyiv was to take this liminality as a point of departure, in order to imagine a new kind of institution.

Among the different schools which were part of The School of Kyiv, the School of Abducted Europe aimed at transgressing the neocolonial relationship between the European metropolis and its peripheries, exploring the potential for transformation of the European project under pressure from the “outside.” The School of Abducted Europe tried to make transgressive steps to overcome the status quo of Ukraine being a double periphery and to study these imagined “centers,” like Russia or Western Europe, from Kyiv. Other schools used the medium of performance as a healing procedure for the collective trauma framing the main emotional horizon of the Ukrainian context. The School of Image and Evidence interrogated how to deliver visual and public messages today, in order to oppose a hybrid media warfare. Some artists (like Hito Steyerl, Artur Żmijewski, Ricardo Basbaum and Neil Beloufa) were invited to produce pieces in Kyiv, together with the participants of the schools, in a horizontal collaboration.

The biennial aimed at producing a new public, expanding the contemporary art and cultural circle approaching people coming from very conservative institutions inherited from Soviet times, where the Biennial was also activated. It was about the opening of new spaces, which is also always about new politics. Spaces were, as Adorno put it in his work Minima Moralia, where “one could be different without fear” (Adorno, 2010).

Processes of “instituting otherwise” as the one of the School of Kyiv, as Maria Hlavajova suggests, are achieved by envisioning the institution from its very beginning as a ‘matrix’ of possibilities rather than fixed contents or structures.”[16]

The School of Kyiv explored the power of art to imagine new scenarios operating according to what the philosopher Donna Haraway defines as “politics of affinity”, using theater, performance, collaboration, and at the same time antagonism as possible forms of dialogue and negotiation. According to Haraway, a political organization structured by the principle of affinities is an organism able to recognize partial identities and contradictory points of view.[17]

Under this notion, I reunited in an exhibition titled The Politics of Affinity, Experiments in Art Education and the Social Sphere,[18] a series of initiatives that interpret pedagogies as a conscious participation and shared strategies, a practice of laborious attempts at overcoming the habit of a split-ontology of “us versus them”, bridging micropolitical engagement with territory on a local scale, with attention to the wider political scenario. The idea was to present many distinctive approaches to the ways in which processes of knowledge production and education might be institutionalized and fostered. The examples spanned from small-scale institutions and educational programs initiated by artists, architects, or curators to pedagogical experiments enacted inside or parallel to established institutions. The essential questions focus on how different models of instituting, exhibition making, and educational programming shaped the engagement with each specific context. What does it mean to politicize art and education in different historical, political, and economic contexts of the post-welfare West, post-socialist Eastern Europe, the non- state condition of Palestine, or within the dynamics of the Global South along the lines of former empires, from the Caribbean and Puerto Rico to Spain? Featuring actions and performances, documentation, installations, and films produced within pedagogical programs by their members and participants, the show aspired to demonstrate the variety of practices, methods, and mediums employed to pursue affinity as a pedagogical and institutional model aimed at the production of critical knowledge. Through methodologies of radical pedagogy, militant research, and institutional activism, the idea of the “classroom” was redefined in these programs as a democratic space, and the study room turned into a laboratory in which the social contract could be rewritten.

One can see this very clearly for instance in the educational program of Campus in Camps, whose efforts are directed at avoiding the pervasive “colonization of knowledge” that comes from internalized ideas, often channeled through decades of humanitarian interventions and territorial occupation, which reinforces the idea of the camp as a site of impermanence rather than one of complex knowledges and histories.

Louis Henderson, Black Code/Code Noir, 2014, film screened t the occasion of Louis Henderson Masterclass at the School of Images and Evidences, part of The School of Kyiv— Kyiv Biennial 2015. Image courtesy The School of Kyiv— Kyiv Biennial 2015.

The many examples I mapped in The Politics of Affinity demonstrate how certain struggles become relevant in the same period over different geographies, many of them in situations of liminality and social transition. As the political philosopher Sandro Mezzadra points out, “the problem of transition reemerges in each historical moment when the conditions of translation have to be established anew”[19]. What he means by translation is the process by which different, often contrasting, cultural-historical experiences are rendered mutually intelligible and commensurable. Mezzadra’s thought is applicable to the current moment when the making of a post-pandemic future on a more environmental and socially sustainable base is required for a common transnational action. Rather than thinking about translation as a binary phenomenon, we should therefore interpret it along with a politic of the pluriverse, a process by which the excluded within the project of universality are included in our present discourse. According to Judith Butler, translation should push its limits, bringing about social change and opening new spaces of emancipation[20]. It is through the enactment of subversive practices, which change everyday social relations and negotiate the epistemic hierarchies of the institution, that such change will probably be possible.

Adorno,Theodor. 2010. Minima e Moralia: Reflection from Damaged Life. London: Verso.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1987. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. New York: Aunt Lute.

de Sousa Santos, Boaventura. 2007. “Beyond Abyssal Thinking: From Global Lines to Ecologies of Knowledges.” Review 30 (1): 45–79.

de Sousa Santos, Boaventura. 2014. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide. London and New York: Routledge.

Escobar, Arturo. 2007. “Worlds and Knowledges Otherwise.” Cultural Studies 21 (2): 179–210.

Mignolo, D. 2000. Local Histories / Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Mignolo, D. 2011. “Geopolitics of Sensing and Knowing: On (De)coloniality, Border Thinking and Epistemic Disobedience.” Postcolonial Studies 14 (3): 273

Mignolo, Walter D., and M. Tlostanova. 2012. Learning to Unlearn: Decolonial Reflection from Eurasia and the Americas. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 1988. “Can the Subaltern Speak?.” In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by C. Nelson and L. Grossberg, 271–313. Basingstoke, England: Macmillan Education.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 1990. “Strategy, Identity, Writing” in The Post-Colonial Critic, edited by Sarah Harasym. London and New York: Routledge, 42.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 2009. Outside in the Teaching Machine. London and New York: Routledge.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 2012. An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

This idea was elaborated by Anselm Franke in his text “The Third House” https://www.glass-bead.org/article/the-third-house/?lang=enview

2.

Dipesh Chakrabarty, Translating Life-Worlds into Labor and History in Provincializing Europe. Postcolonial Thought and historical difference, Princeton University Press, 2000, pp 72-96

3.

The full group also includes Edgardo Lander, Ramón Grosfoguel, Agustín Lao-Montes, Zulma Palermo, Catherine Walsh, Arturo Escobar, Fernando Coronil, Javier Sanjinés, Santiago Castro-Gómez, María Lugones, and Nelson Maldonado-Torres.

4.

Boaventura de Sousa Santos, Joao Arriscado Nunes, and Maria Laula Meneses, “Opening Up the Canon of Knowledge and the Recognition of Difference,” in de Sousa Santos (2008, xlix), reprinted at http://www.boaventuradesousasantos.pt/media/Introduction(3).pdf.

5.

Boaventura de Sousa Santos, B. “Beyond Abyssal Thinking: From Global Lines to Ecologies of Knowledges.” Review30, no. 1 (2007): 45.

6.

Julieta Gonzalez, “Memories of Underdevelopment: Early Instances of Decolonial Aesthetics and Epistemic Disobedience in Brazilian Architecture, Film, Art, and Theatre, 1960–1980” (MA thesis, Goldsmith, University of London, date unknown).

7.

Carla Zollinger, “Lina Bo Bardi and the Bahian Modern Art Museum: museum-school, museum in progress,” text commissioned for the 2012 exhibition Lina Bo Bardi: Together, available at http://linabobarditogether.com/it/2012/09/02/lina-bo-bardi-and-the-bahian-modern-art-museum-museum-school-museum-in-progress/.

8.

Julieta Gonzalez, “Memories of Underdevelopment: Early Instances of Decolonial Aesthetics and Epistemic Disobedience in Brazilian Architecture, Film, Art, and Theatre, 1960–1980” (MA thesis, Goldsmith, University of London, date unknown)

9.

The exhibition was held at SALT in Istanbul in 2014. The monograph Global Tools 1973-75. Towards an Ecology of Design (Nero Publishing 2019) contains the full history of this experimental pedagogical and institutional initiative.

10.

Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe. Postcolonial Thought and historical difference, Princeton University Press, 2000

11.

Dipesh Chakrabarty, The Climate of History in a Planetary Age, Chicago University Press, 2021

12.

Abdelmalek Sayad, La Double Absence, Editions Seuil, 1999

13.

The program was supposed to be launched with the symposium “Fabrica Mundi: Making, Unmaking, Remaking Worlds”, which was announced but did not take place as a cause of the SARS Covid Epidemia.

14.

The team was led by Georg Schöllhammer and Hedwig Saxenhuber and composed by Michaela Geboltsberger and myself.

15.

In 2014-2015 a crisis in Ukraine unfolded following the Euromaidan protests associated with the emergent social movement of integration of Ukraine into the European Union, the February 2014 Maidan revolution and the ensuing pro-Russian unrest.

16.

Instituting Otherwise, A conversation with Maria Hlavajova about BAK, basis voor actuele kunst in Franceschini, Silvia, ed. 2018. The Politics of Affinity: Experiments in Art, Education and the Social Sphere. Biella, Italy: Cittadellarte—Fondazione Pistoletto.

17.

Donna Haraway, A Cyborg Manifesto: Simians, Cyborg and Women: The Reinven- tion of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1991), p.154

18.

The exhibition The Politics of Affinity. Experiments in Art, Education and The Social Sphere took place at Cittadellarte – Pistoletto Foundation in 2016

19.

Sandro Mezzadra, Living in Tran- sition: Toward a Heterolingual Theory of the Multitude, Eipcp multilingual web journal, June 2007. Online at: http://eipcp.net/ transversal/1107/mezzadra/en.

20.

Judith Butler, Gender in Translation: Beyond Monolingualism, https://philpapers.org/rec/BUTGIT

21.

Riccardo Dalisi, Animazione Rione Traiano, 1971-1975, Archivio Riccardo Dalisi, riconosciuto di interesse culturale dalla Soprintendenza archivistica e bibliografica della Campania. The images are featured in the publication by Valerio Borgonuovo and Silvia Franceschini, Global Tools. 1973-1975 When Education Coincides with Life, Nero Editions, Rome, 2019.

is a curator and researcher working across the fields of visual arts, design, and architecture. Until autumn 2021 she has been an Associate Curator at Z33 – House for Contemporary Art, Hasselt, Belgium. She has in different contexts been working with issues of pedagogy and spaces for learning and knowledge production and in her PhD thesis Toward an Ecology of Knowledges: Critical Pedagogy and Epistemic Disobedience in Contemporary Visual Art and Design Practices she explored and discussed in depth historical and contemporary theory and practice in this field. Curatorial projects include: Le Déracinement. On Diasporic Imaginations, Z33, Hasselt (2021); research program The Politics of Affinity. Experiments in Art, Education and the Social Sphere, Cittadellarte-Fondazione Pistoletto, Biella (2016–18); participation on the curatorial team of The School of Kyiv—Kyiv Biennial 2015; and the exhibition, symposium, and educational program Global Tools 1973–1975: Towards an Ecology of Design, SALT, Istanbul (2014). Silvia Franceschini is an editor of The Politics of Affinity. Experiments in Art, Education and the Social Sphere, Cittadellarte – Fondazione Pistoletto, 2018, and a co-author of Global Tools 1973–1975. When Education Coincides With Life, Nero Publishing, 2019.