A funambulist: Unearthing the narratives of Karachi’s colonial and national (postcolonial) formation

Behzad Khosravi Noori

CATEGORY

Embarking on a journey to explore and teach the decolonised history of Karachi, Behzad Khosravi Noori intertwines his personal historical explorations with pedagogical practice. How do we approach history in Karachi? How can we envision an alternative future for our collective past?

The journey to Karachi spans 13 hours. As I make my way to the airport’s exit, no matter how familiar I am with the airport, I rely on signs in both Urdu and English to guide me. Interestingly, the Urdu signage appears more decipherable, possibly owing to its proximity to my native Farsi. Among these signs, I always notice the one in Urdu that reads “International Departures” ( بین الاقوامی روانگی ). It strikes me that translating this sign into Farsi and then from Farsi to English gives it a new dimension, completely altering its dry, formal, and definitive airport signage character. The Urdu term “روانگی” translates into Farsi as “روان بودن,” which means “fluidity.” Similarly, “بین الاقوامی” becomes “میان دو قوم یا طایفه” in Farsi, signifying “amidst ethnics”. Consequently, the sign for “International Departures” now takes on a literal translation of “میان دو قوم یا طایفه روان بودن.” “Entangle Ethnics Fluidity”

Here, I reflect on my itinerancy and entangled ethnic fluidity as an educator, simultaneously navigating the diverse educational territories in Karachi and London. It’s a chronicle of my experiences, challenges, learnings and failures while teaching in these two locations. Being an educator is not merely an attachment to my artistic practices; rather, it is an integral part of my intellectual and artistic characteristics. I don’t teach to produce new artwork with students. I believe that creating a collective artwork with students can be challenging and problematic, as the role of a teacher often involves the need to structure and guide ideas. In my classroom, the discussions, debates, lectures, and, perhaps most significantly, assignments are not rigidly structured but rather reflect my enthusiasm, moments of uncertainty, desires, and failures – questions and challenges that I share with my students.

I use the umbrella term artistic re-search to describe what I do both in my teaching and my arts. My pedagogical journey attempts to explore the potential of doing research through art and by art. While I refer to it as “artistic re-search” for now, you are welcome to employ different terminology if you prefer. For me, this is not a matter of pitting academic disciplines against each other, nor is it an attempt to define artistic research, as jargon has already done. Instead, I aim to delve into the potential of artistic practices as an alternative possibility for knowledge creation and re-search. This knowledge may emerge from the depths of one’s intuition, moments of joy, periods of sorrow, or even times of profound despair.

Can education be our salvation? I must confess that I don’t have an alternative solution readily available. Despite my extensive criticism of the profound shortcomings of the neoliberal educational system, which has prioritised marketing, commodification, mimicry and the institutionalisation of learning over genuine education, I still hold firm to the belief that the act of teaching, sharing, and engaging in class discussions can have a transformative impact. By posing the question of whether education can save us, I attempt to position myself within two seemingly disparate realms: one in the South, namely Karachi, a port city originally envisioned as the “Liverpool of the Indian Ocean” and the closest port to mainland Europe during the colonial era; the other being London, the capital of the empire and the epitome of metropolitan sociability.[1]

In my role as an educator within the realm of art, I have consciously strived to navigate the false divisions that delineate concepts of “here” and “there,” even seeking to challenge the very notion of such boundaries. I see myself as someone who traverses borders, embodying the essence of an itinerant educator. This mobility is a privilege and an advantage that comes with my itinerant status, the passport, one that I never take for granted. Whenever I present my proof of residency in the Global North at passport control, it is an essential reminder of this privilege. This ongoing act of legally crossing borders inherently inspires me to engage in a comparative critical analysis of the contrasting geographies of “here” and “there.” It provides me with fresh insights into the territorialised experiences of the global North and South, as well as the distinctions between metropolitan and colonial sociability. Whether journeying from Karachi to London or vice versa. Indeed, once you have crossed a border, there is no way to “uncross” it, forever changing one’s perspective and understanding.

My aim isn’t to bridge these territories, as they are inherently interconnected. Instead, I have aimed to explore how to navigate the line, walk along the border, and maintain a delicate balance. I’m not attempting to create a bridge between them; in fact, one is a direct outcome of the other—the British-built Karachi following General Napier’s invasion of Sindh in 1843. It feels as though I’m not merely crossing borders but traversing the very existence of the border. Here, I try to balance the pasts and futures of these territories; I am a foreigner of both lands – a guest, a funambulist. Poised delicately as much as possible atop the slender border, weaving a dance of equilibrium, every step a tender negotiation between soaring and not falling.

My pedagogical journey was related to exploring the city of Karachi as a live archive and digging into the colonial archive in the British Library and Maritime Museum in London to collect documents about Karachi within the colonial archive. Karachi is the site-specific location for my exploration, a point of departure and a point of return. It is a location that suffers from the claustrophobia of colonial and national formation, the failed capital of the post-colonial nation, the place for the organic crisis, the intersection of social, economic and environmental crisis, the urban hell, the future that we will all live in soon. The organic crisis shapes its history and identity and repeatedly leaves the city and its people alone. As we grapple with the daunting task of decolonising our history, the promise of a post-colonial national reformation appears increasingly elusive, a mirage that fades into obscurity.

The separation between these two territories is not just geographical but epistemological: the way that we know and don’t know the history, the way that history has been invisibilised, the face blindness of history, the prosopagnosia. I physically, mentally and discursively walk in and out of these separated territories. This itinerancy shapes my methodology as an itinerant speculative educator, exploring a kaleidoscope of places, stories and people.

The act of a funambulist is evident even in my writing – writing these words in English. The fact that I am writing to you in English already falsifies what I wanted to tell you. My subject, as Gustavo Perez Firmat describes, is how to explain to you that I don’t belong to English thought. Translating from one language to another is akin to the act of funambulism, a delicate tightrope walk that inevitably gives birth to a new phenomenon, somehow detached from its original essence.

English has been the primary language of instruction and communication during my teaching in Karachi. This circumstance stemmed from the influence of the British colonial administration, which altered the administrative language in India from Farsi to Urdu and English in 1837. Consequently, all my students in Karachi have achieved proficiency in the colonial language, as their high school education predominantly revolved around English. Many of them completed their education through the Cambridge Boards, where using Urdu was penalised with negative grades. This pressure to master English led them to employ more intricate sentence structures and expand their vocabulary, enabling them to effectively engage with and convey complex theoretical arguments unique to art students. This phenomenon became even more apparent when working with my South Asian students at Goldsmith, where we discussed their assimilation into a new culture and society as newcomers despite their superior English skills, sometimes even more advanced than native English-speaking students. The knowledge, or lack thereof, of English language proficiency in Karachi is essential in creating significant class divisions. It can be employed as a means of intimidation against minority individuals attempting to access elite educational institutions, often grappling with imperfect English skills. [2]

You will yet be the glory of the East; would that I could come again to see you in your grandeur.

—Charles Napier, sometimes, Governor of Sind

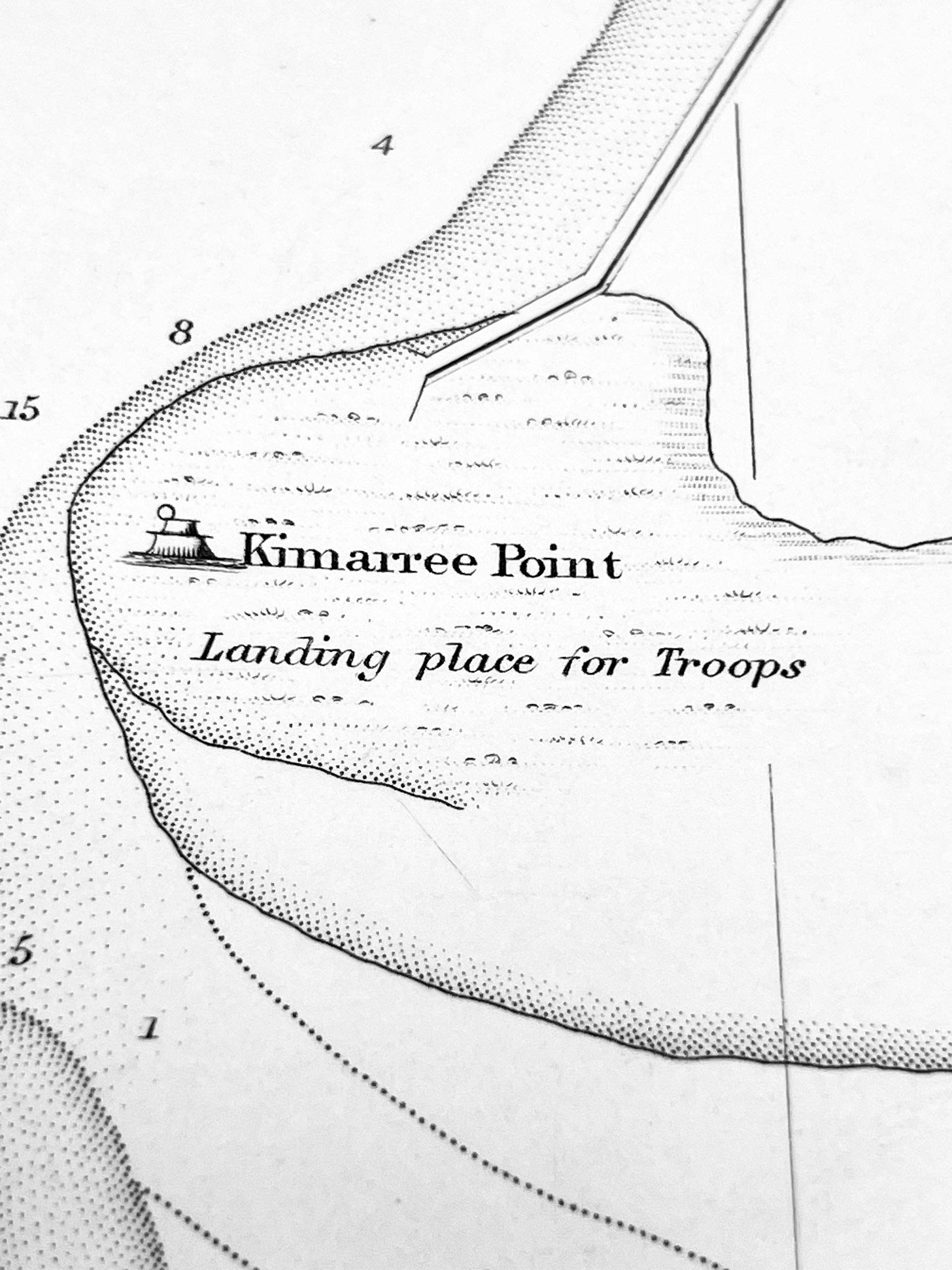

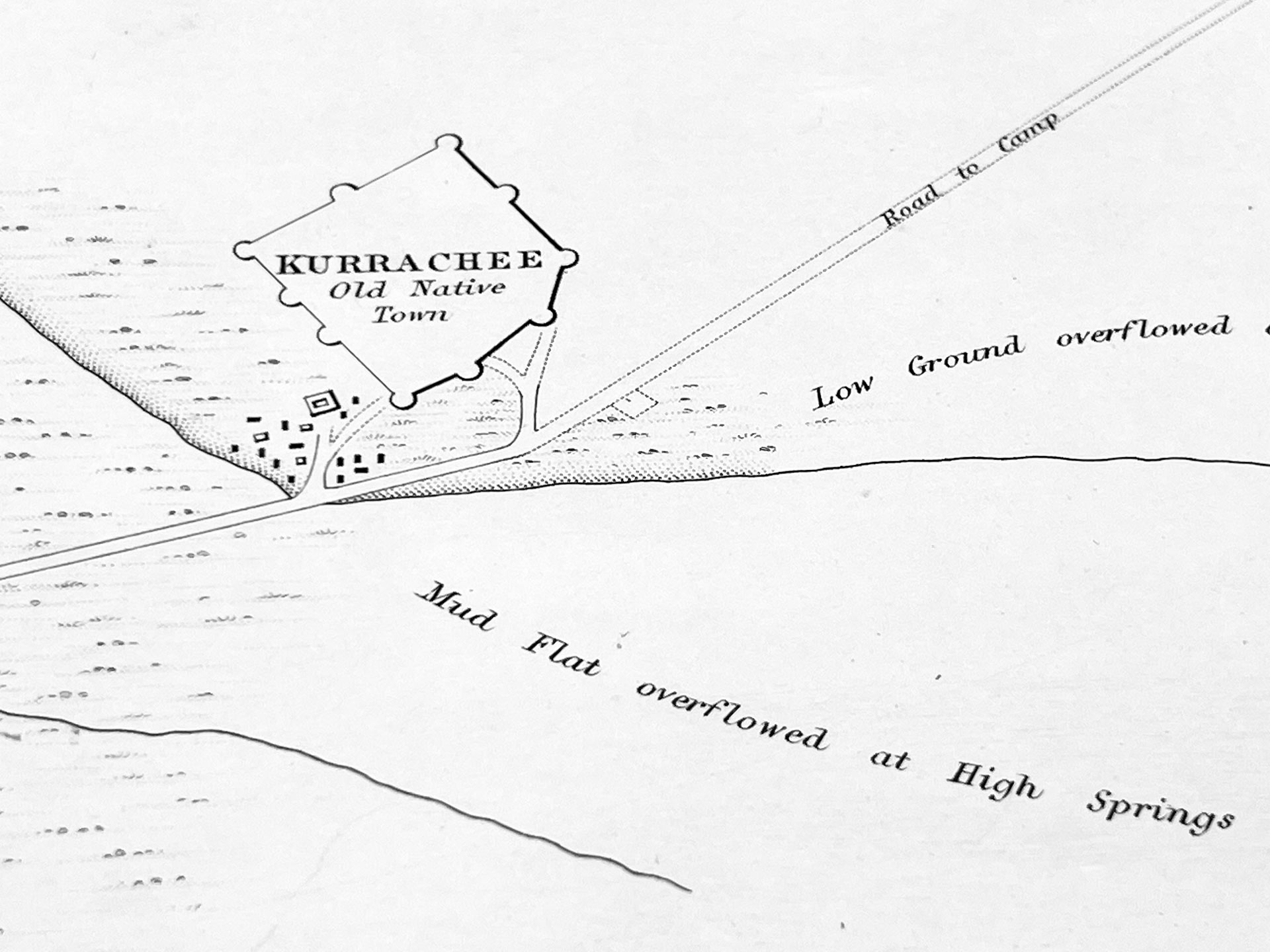

Karachi, once deemed the pearl of the Indian Ocean, grapples with its tumultuous history, woven intricately with the threads of colonisation, independence, and dynamic metropolitan growth. When General Charles Napier seized Sindh on 23 March 1843 and entered Karachi via the island Kiamari, the foundations were laid for a city that would be sculpted by British hands – the city with thousands of names. Depending on how the name is spelled, different documents would appear in different archives and periods.

Detail of the map of Kurrachee, surveyed December 1849, C. D. Campbell Comm. I. N. British Library. Photo by the author

Detail of the map of Kurrachee, surveyed December 1849, C. D. Campbell Comm. I. N. British Library. Photo by the author

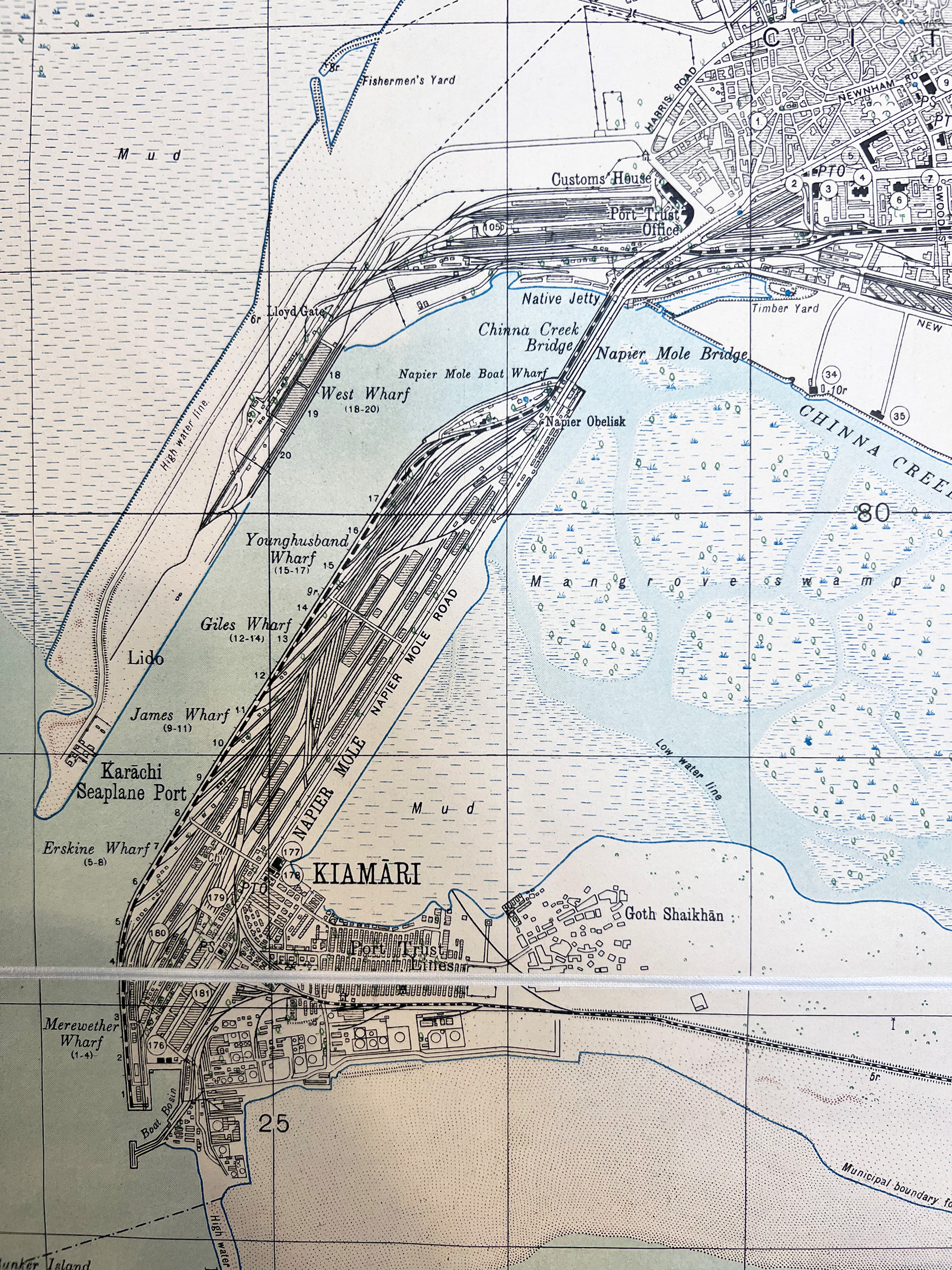

Karachi Guide Map, 1st Edition 1929, 2nd (revised) 1940, Reprinted 1944 August. British Library. Photo by the author

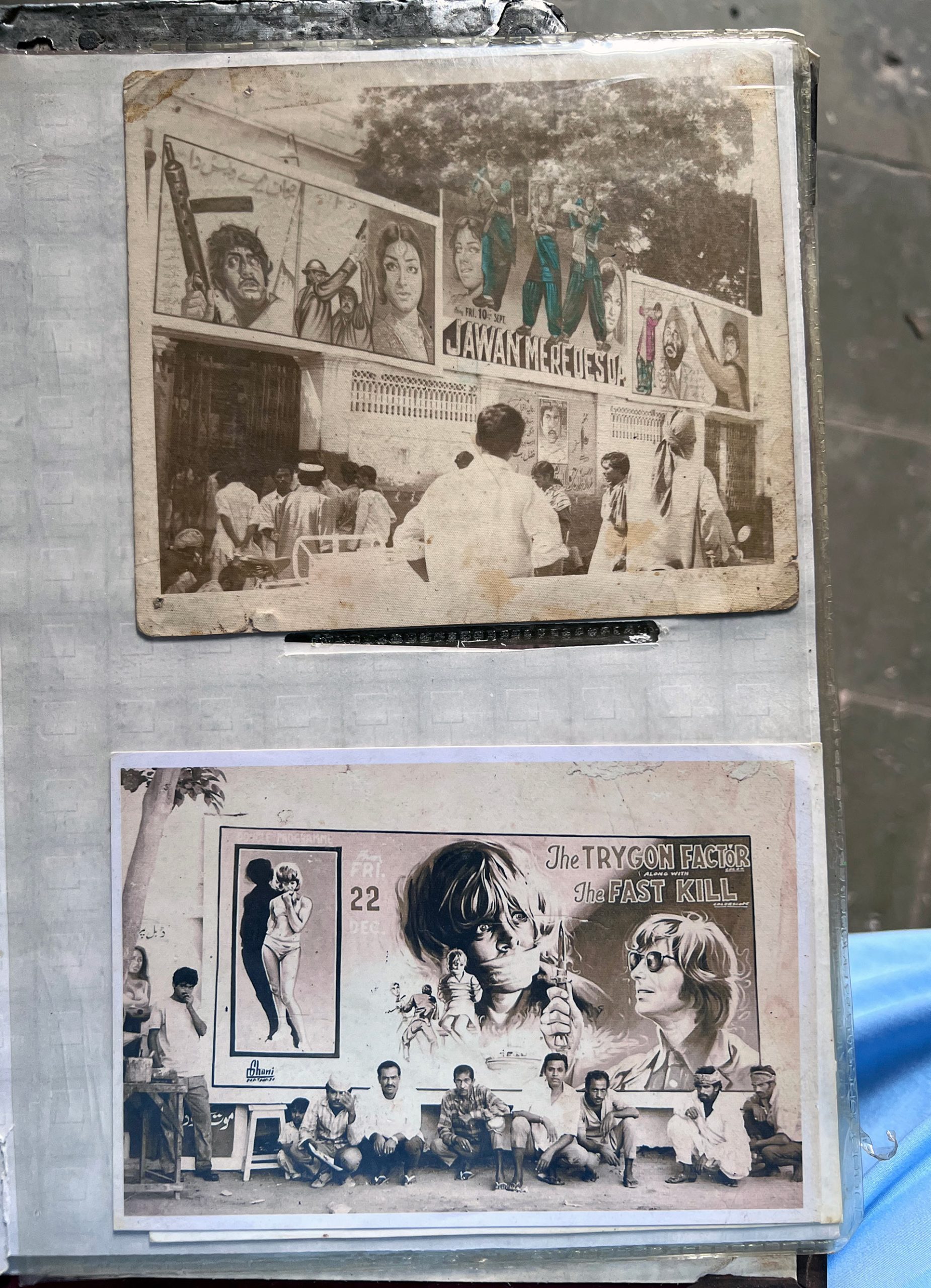

To connect with the mainland, James Napier constructed a road that continues to bear the name of the invader of the Sindh – Napier Road. This road now intersects with a red-light district in Karachi, once the heart of the city’s cinema and entertainment industry. However, that industry has long ceased to exist, and today, only remnants remain as reminders of its bygone era. Among these remnants, one can find a painting workshop tucked away inside a decaying cinema, which once thrived during the city’s heyday in the 1960s and 1970s when Karachi earned the nickname “City of Lights” due to its bustling nightlife.

Parveez Studio, Napier Road, Karachi. Photo by the author

During the mango season, the abandoned cinema building situated on Napier Road in Karachi is used as a transportation and storage facility. Photo by the author

The Trygon Factor is a 1966 British-West German crime film, Parveez Studio, Napier Road, Karachi. Photo by the author

Statue of Charles James Napier, erected on the southwest plinth in Trafalgar Square, George Gammon Adams, 1856, London. Photo by the author

An abandoned cinema in the intersection between Napier and Nishat Road, Karachi. Photo by the author

Napier Road starkly contrasts the Napier statue at Trafalgar Square in the heart of London. It’s imaginable that James Napier envisioned a similar honour for himself in Karachi.

In this conjunction of past and present of phantasy and entertainment, the question arises: what does the decolonial history of Karachi look like, especially for a metropolis shaped significantly by its colonisers? Is there any method of decolonial investigation of the city and its sociabilities? Or everything shifted from a colony to a new colony?

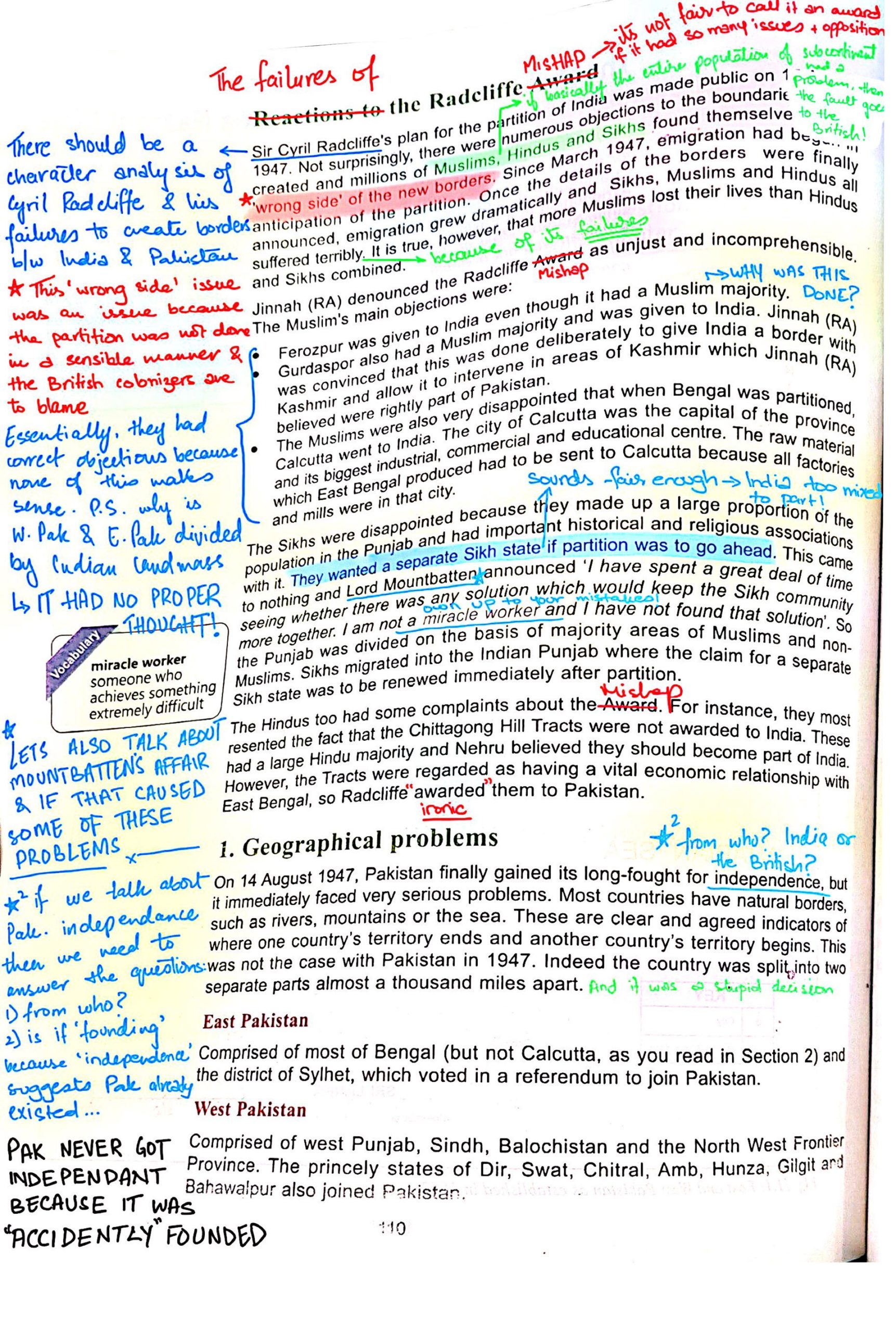

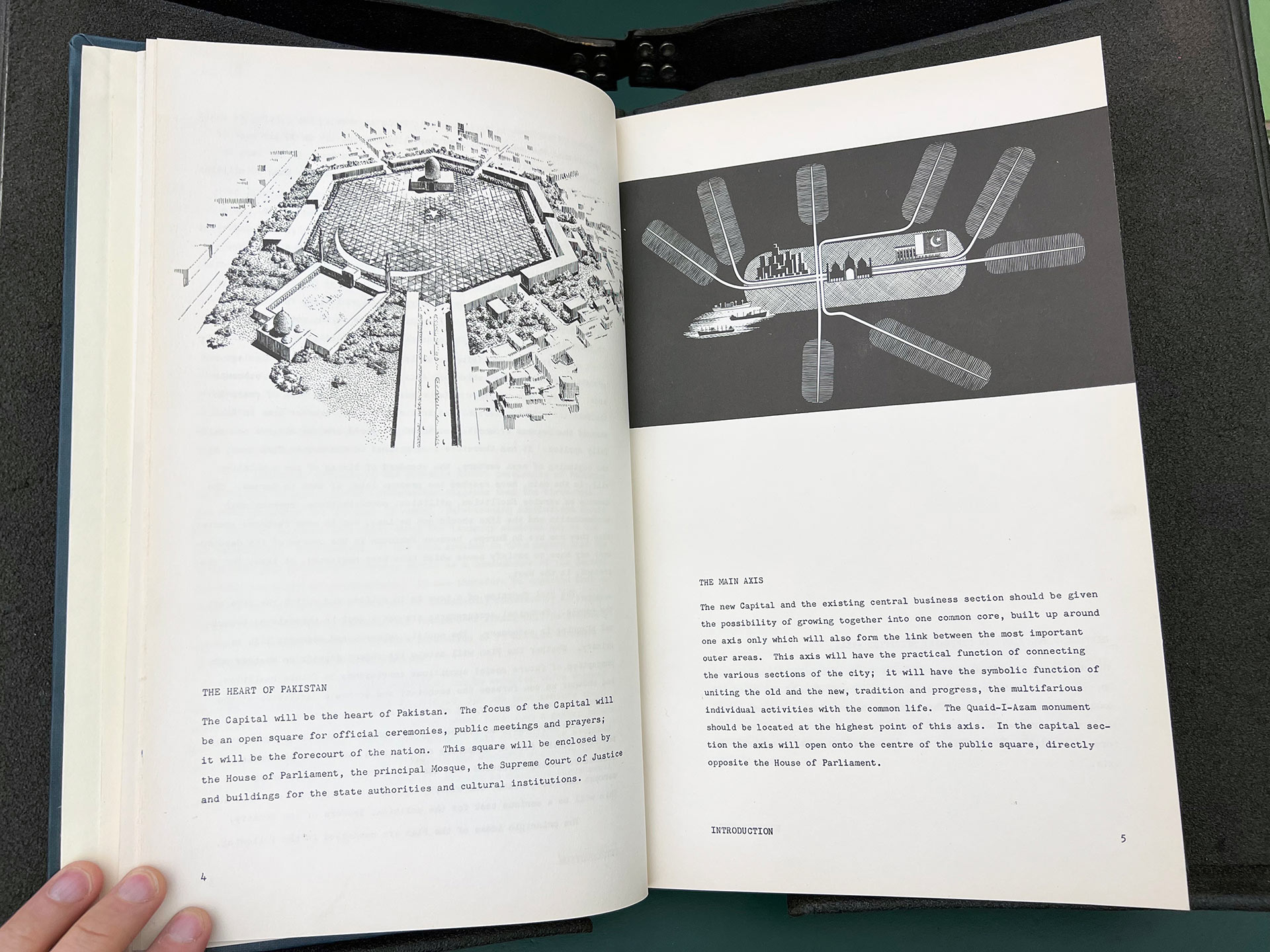

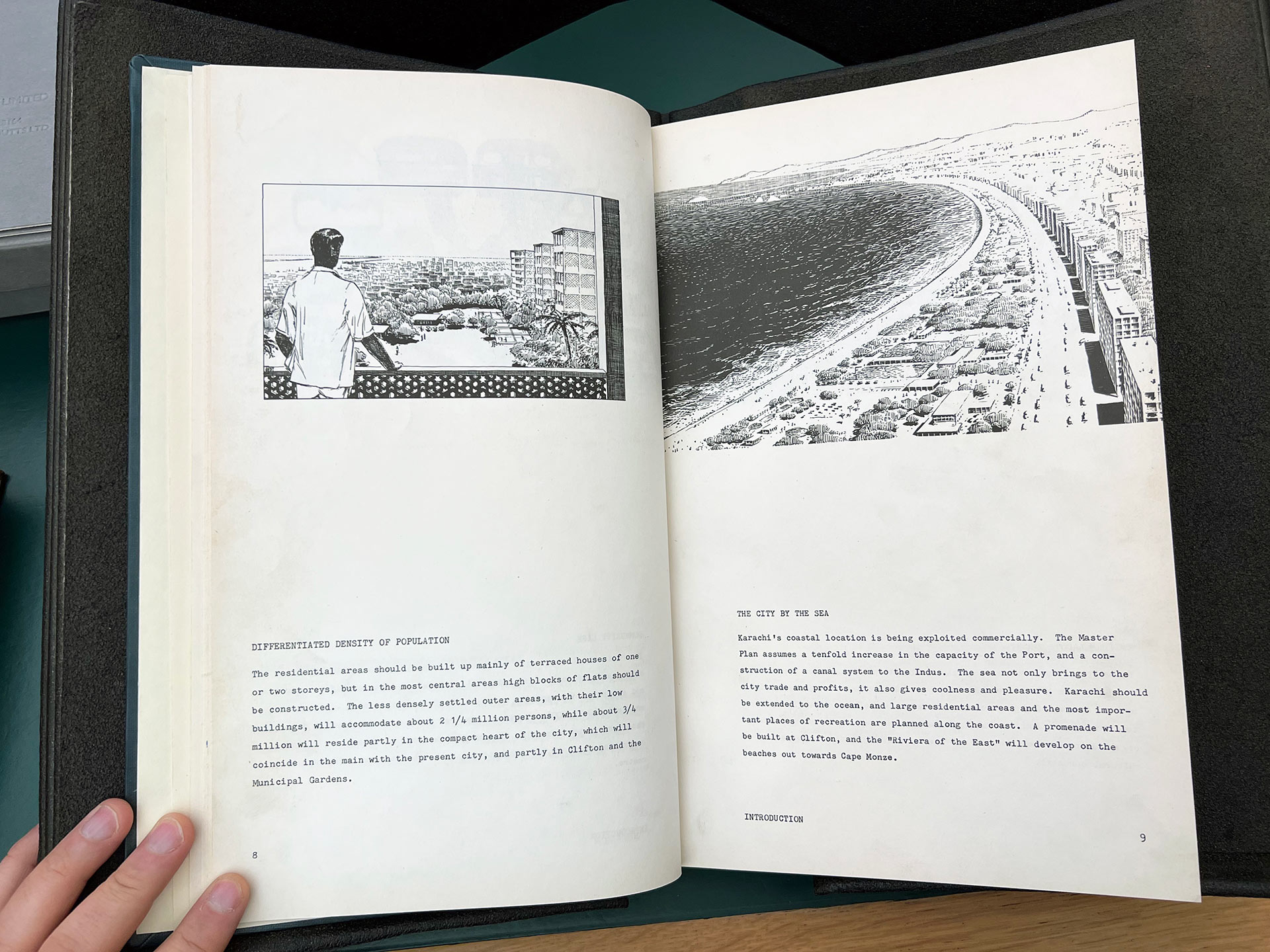

Envisioned as the ‘Pearl of the Indian Ocean’ during the colonial era, Karachi assumed the role of Pakistan’s capital in the early stages following its partition from India in 1947. Despite its significance and development efforts, including initiatives by the Swedish company Vattenbyggnadsbyrån (V.B.B) in April 1952, based on a preliminary report from December 1949, as well as contributions from Greek city planner Constantinos Apostolou Doxiadis and his Entopia concept, the city encountered preservation and sustainability challenges. These challenges stemmed from the presence of millions of refugees who had settled in Karachi’s streets since the partition, even though a pilot project for a new urban life had been established in the Korangi district. Ultimately, the capital designation was transferred to shift the Pakistani capital to the north, birthing Islamabad. Karachi stands as a testament to a project that didn’t quite meet its aspirations, a capital that faltered, and a heterotopic space where the concept of utopia has repeatedly stumbled. Yet, paradoxically, it continues to be the world’s fastest-growing city.

Report of Greater Karachi Plan, Merz Rendel Vatten, 1952, British Library, London Photo by the author

Merz Rendel Vatten proposal for new Karachi, British Library, London. Photo by the author

My argument here is not in relation to colonials and national formation of what India and Pakistan are as there have been massive interesting scholarly works being done; my desire here is to see how to teach art and history in the city which has been built by colonial mindset as a segregated urban society since 1843. Talking about the critical reading of what is considered heritage without a description of colonialism and the method of decolonisation is impossible. So the task is simple: how do you talk about art and history?

Embarking on a journey to explore and teach the decolonised history of Karachi, I intertwined my personal historical explorations with pedagogical practice. A central question shaped my teachings and explorations: how does one unearth the narratives of Karachi’s colonial and national (postcolonial) formation, which remain obscured under the vast umbrella of widely accepted historical narratives?

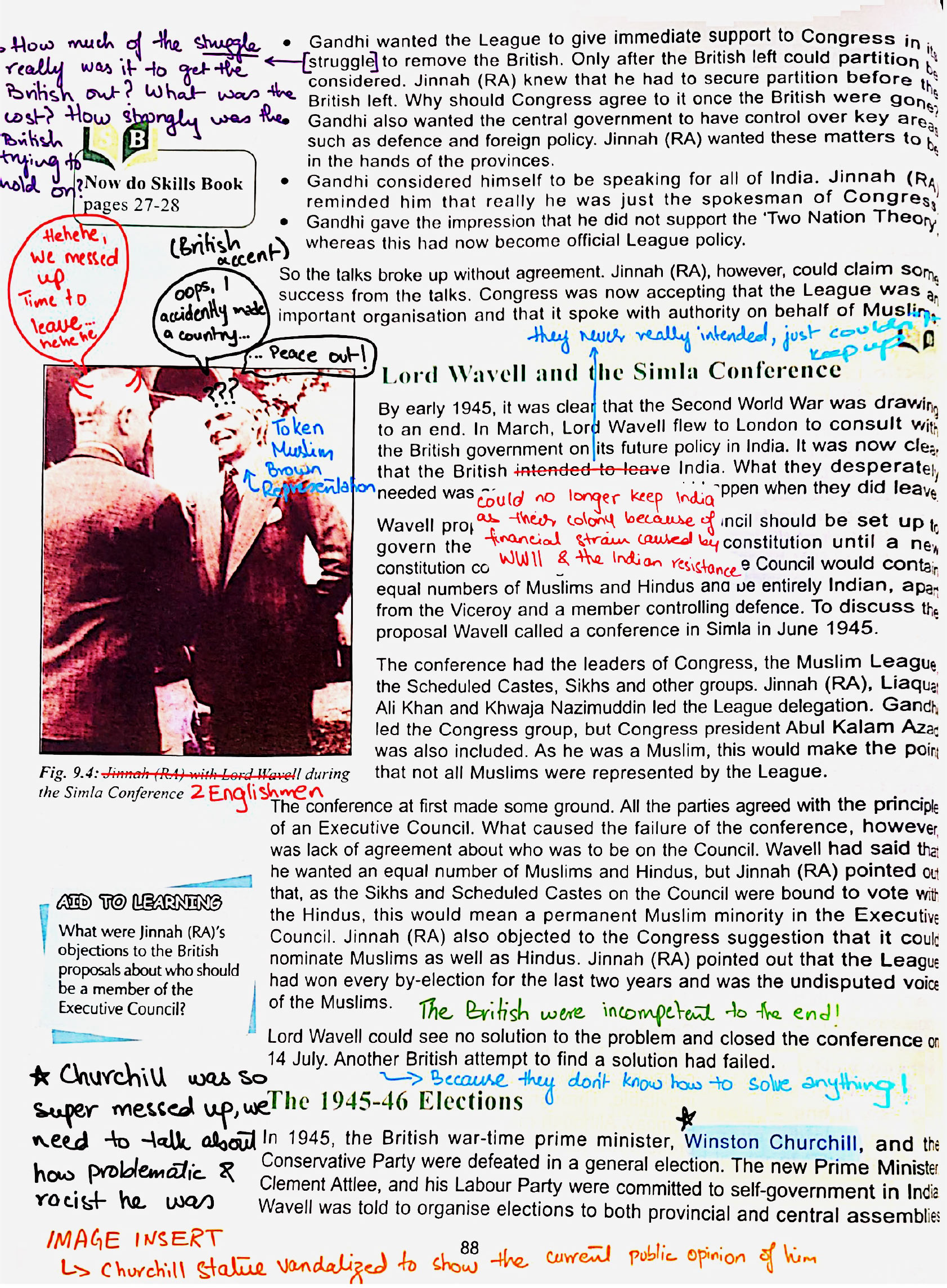

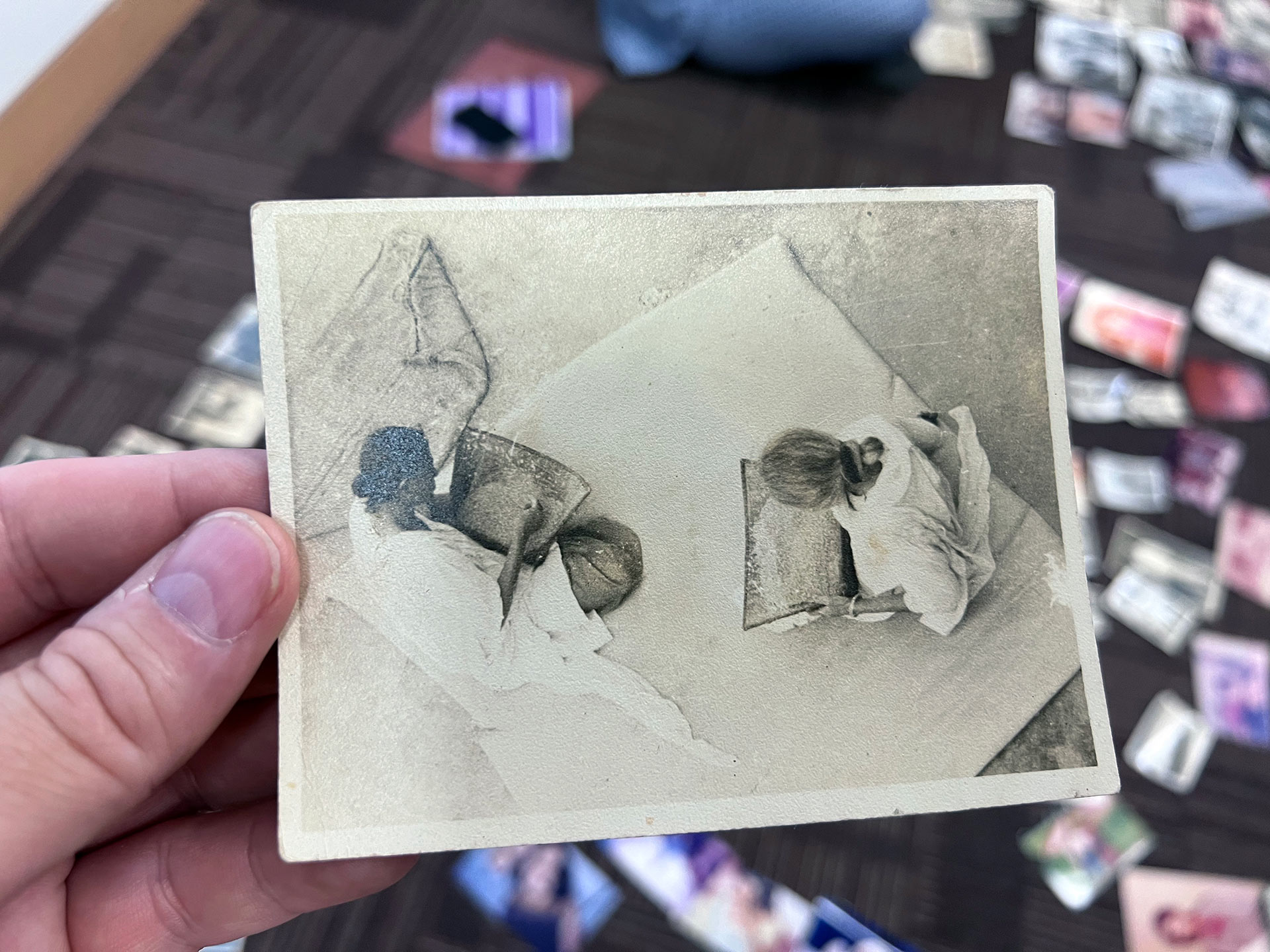

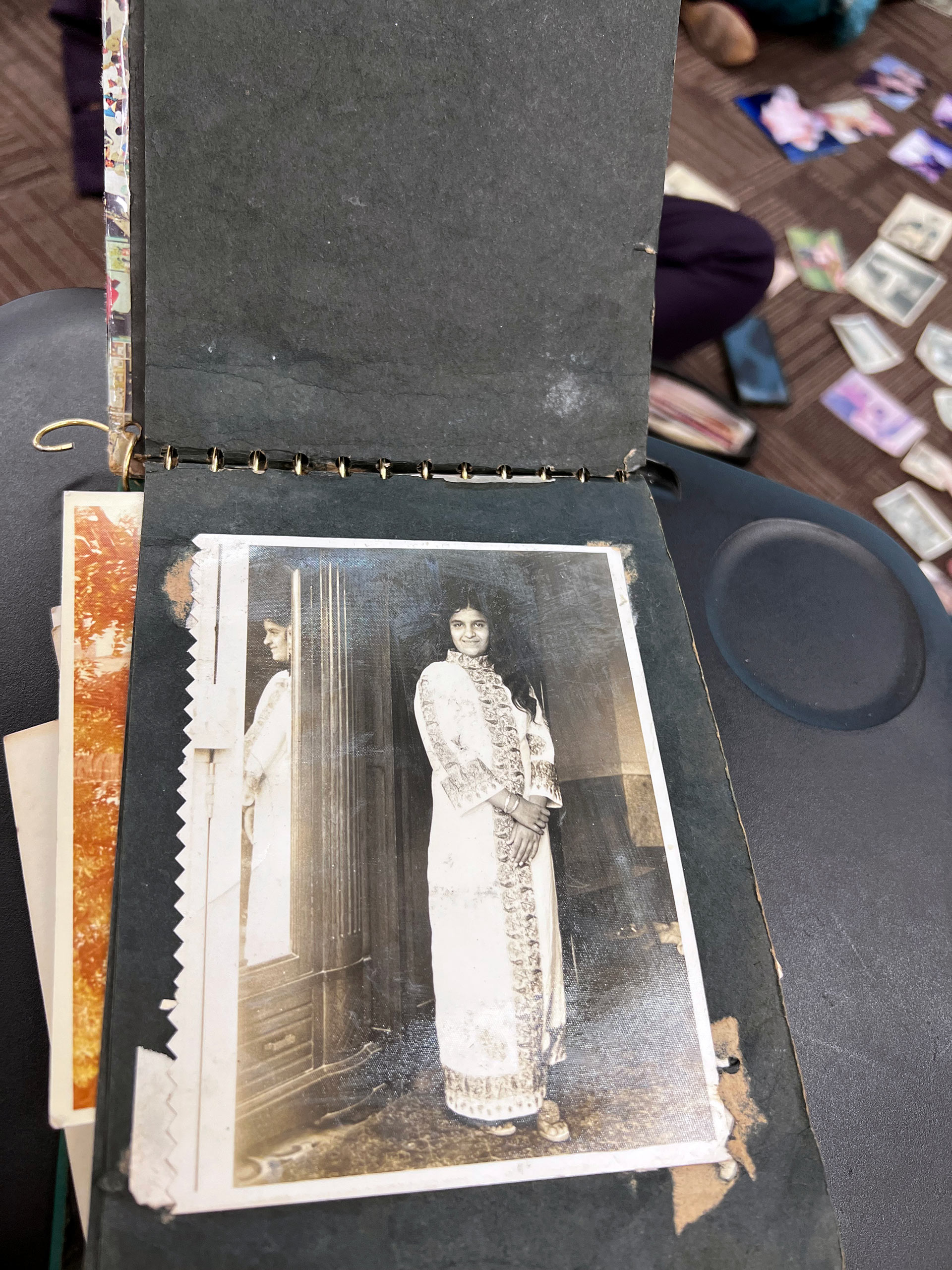

Asfiya Ghanchi’s family album, Landscape of Imagination course, Habib University, 2022. Photo by the author

Asfiya Ghanchi’s family album, Landscape of Imagination course, Habib University, 2022. Photo by Dillip Kaka

The “Landscape of Imagination” course significantly departed from the conventional focus on image production and amateur photography in South Asia. Following my auto-ethnographical investigation of my grandfather’s photography archive and the practice of photography by a handmade camera known in Urdu as “Soul Catcher” [3], I delved into the contemporary history of Karachi, particularly from the perspective of third-generation Pakistanis post the 1948 partition and the associated amateur photography practices. The cross-disciplinary course at Habib University aimed to bridge the gap between amateur photography and family albums, exploring the diverse aesthetic choices that shaped these images. Its primary objective was a critical examination of the colonial and national formation of today’s society through the lens of third-generation Pakistanis. This exploration sought to challenge the politics of positionality within the multifaceted landscape of Karachi, which boasts a complex and direct history of colonialism. “Landscape of Imagination” could be seen as a methodological proposition rooted in contemporary archaeology. It prompted students to ask questions like, “How do we approach history in Karachi?” and “How can we envision an alternative future for our collective past?”

Alinaz Shiraz’s family album, 2022, Landscape of Imagination course, Habib University, 2022. Photo by the author

Asfiya Ghanchi’s family album, Landscape of Imagination course, Habib University, 2022. Photo by Dillip Kaka

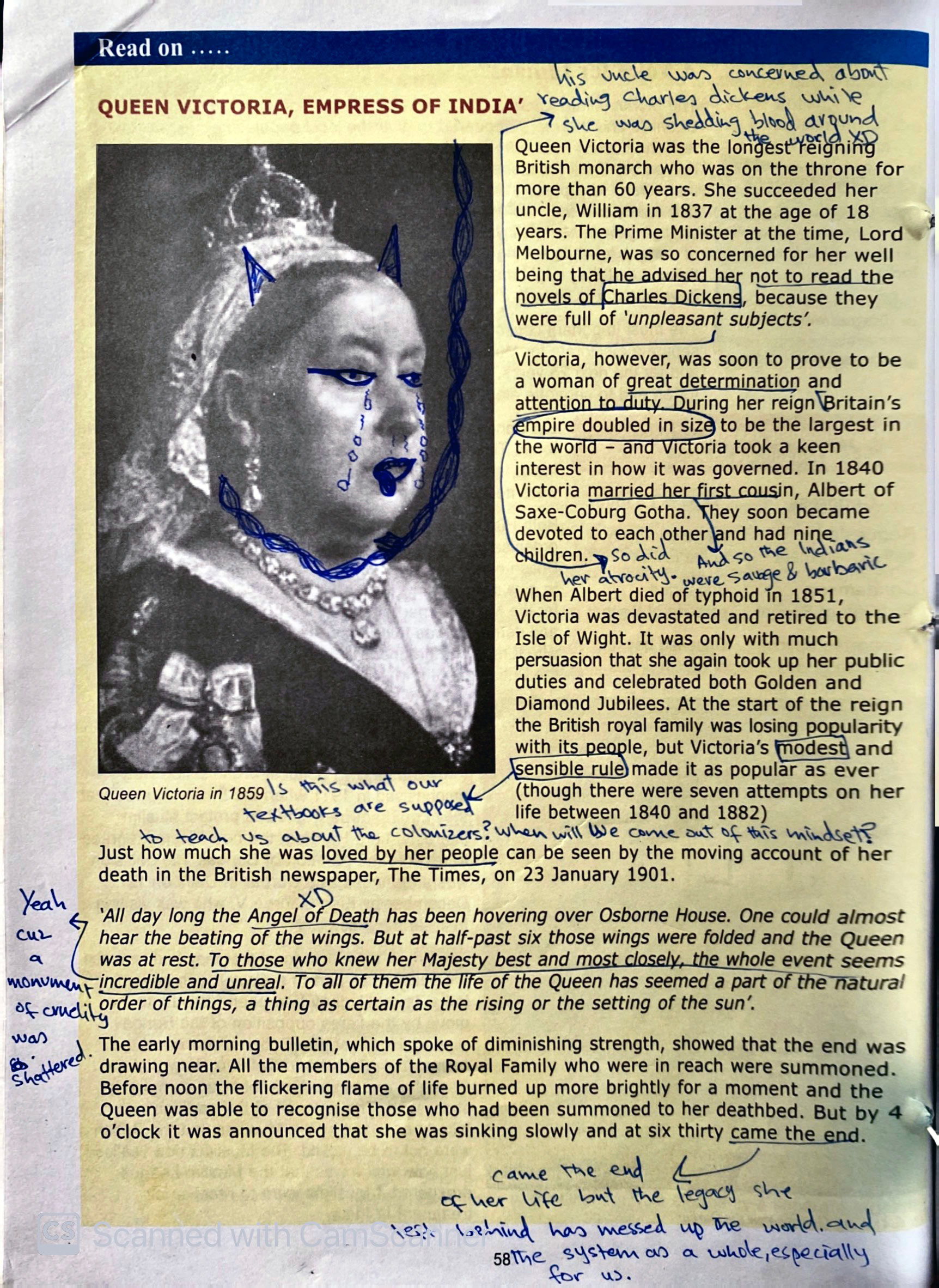

The course transformed into this vibrant space where my students and I shared stories, uncovering hidden histories tucked away in family albums and personal tales. It wasn’t just about dissecting theories on postcolonialism; it was a heartfelt journey into the intricate walk between history and art. Some of the student’s stories we unearthed were downright unexpected. Like the mom who posed as Mohammad Ali Jinnah over and over for her husband’s camera. Or the grandma who idolised Queen Elizabeth and made sure she was the star at every family gathering, channelling her inner queen in white clothes. We found a series of photos where relatives acted like they were deep in phone conversations and another family who cherished their family photos on the wall so much that even when the images faded completely, they refused to take them down. Or the story of an IPA passenger aeroplane rendered inoperable due to a hijacking incident, later repurposed as a public cinema within the city’s largest theme park. Every presentation was an emotional rollercoaster, filled with chuckles, gasps, and head-scratching moments. We were diving deep into people’s subconscious choices in front of the camera and the stories these images whispered.

The course “Landscape of Imagination” bridges both macro and micro-historical perspectives. This intersection not only facilitated but also ignited the potential for experiencing otherness; the capacity to be other sought to highlight the unconscious influence of colonial memory on our artistic identities and practices. Thus, our exploration was not solely rooted in a historical perspective but in reflecting upon and understanding these coordinates and their imprint on our present.

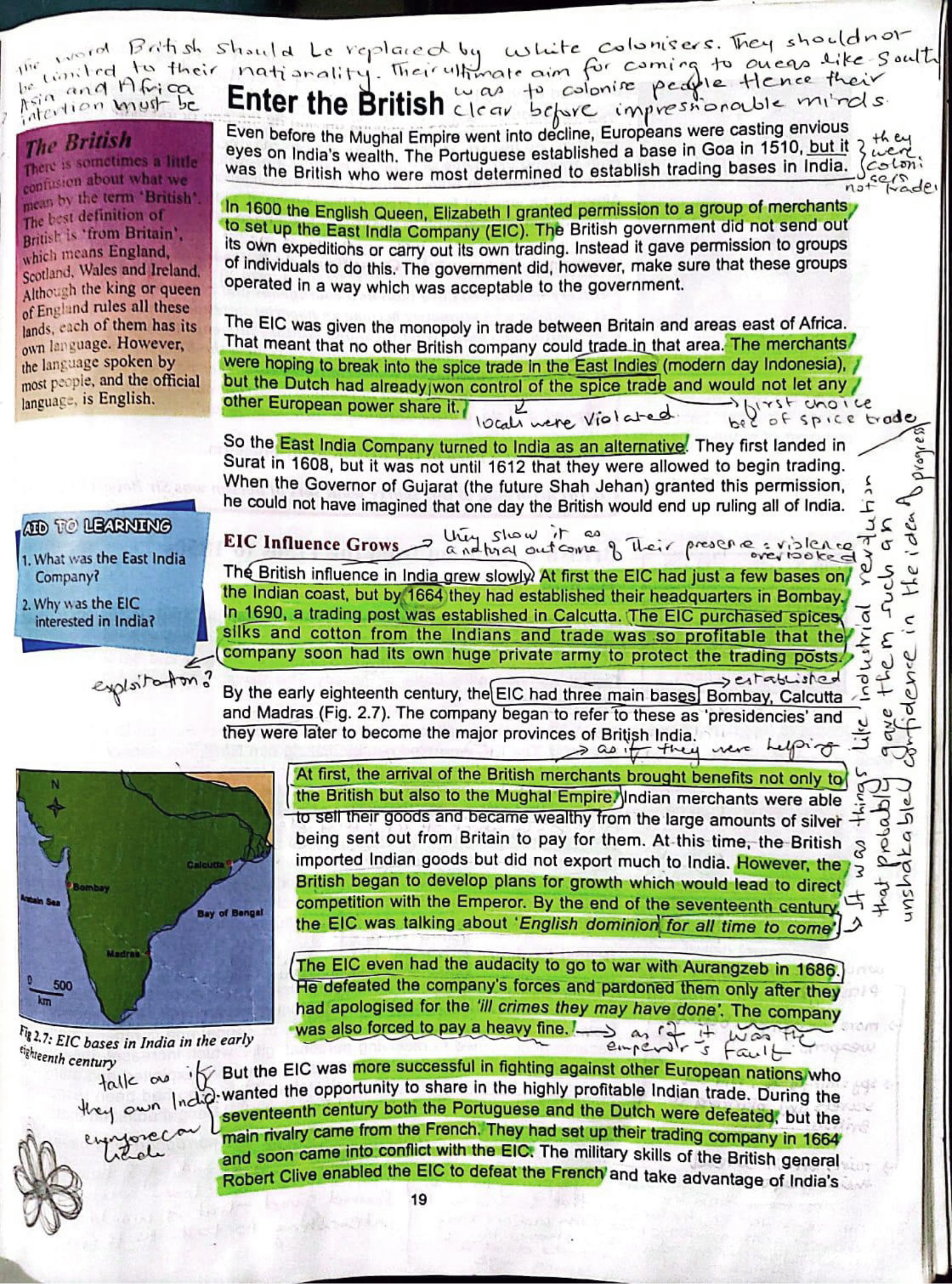

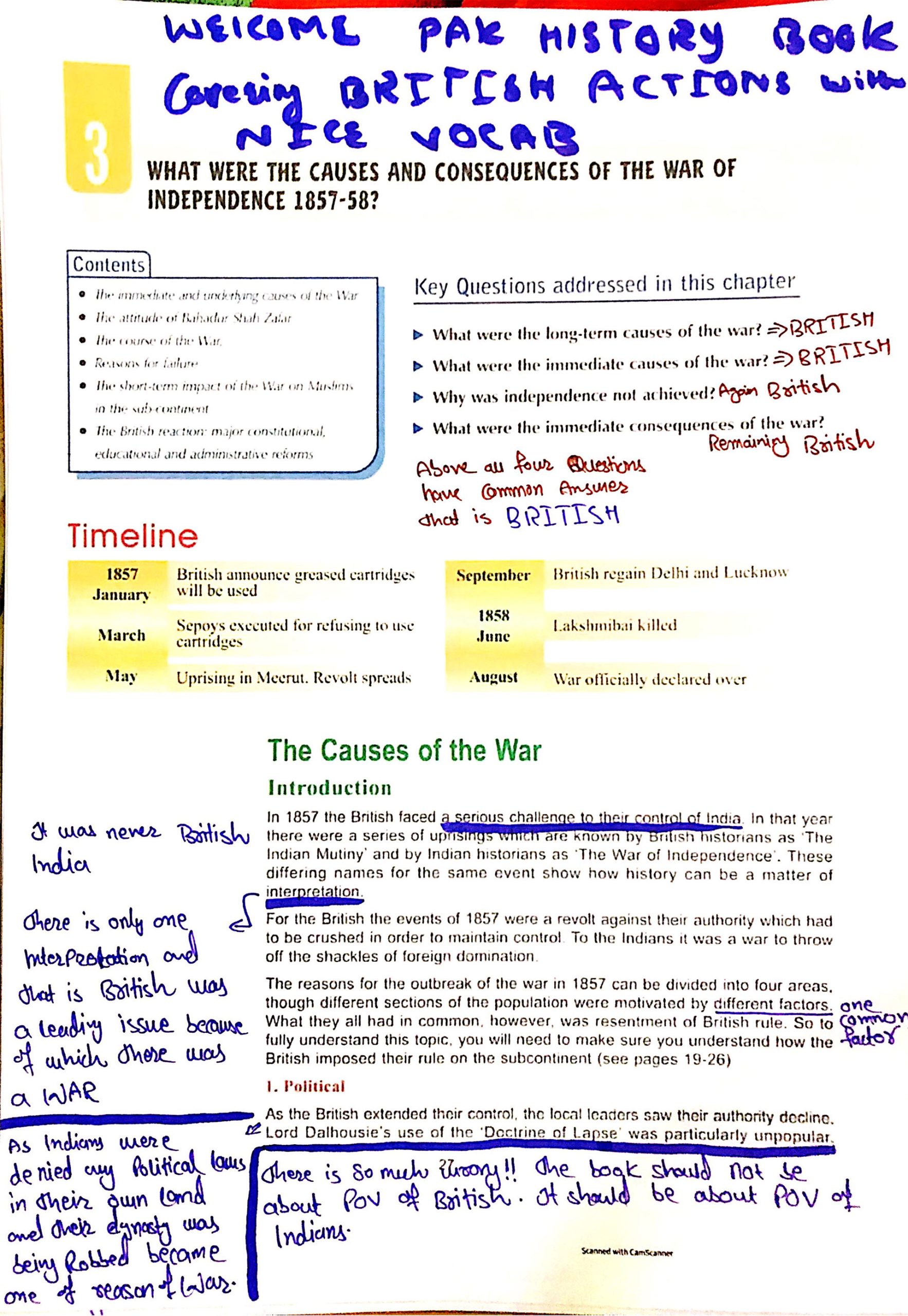

During the discussion, a question repeated why the colonial history of India and Karachi was not a staple in their school curriculum struck a chord. Despite being Cambridge board graduates, many of them had experienced a portrayal of the East India Company that downplayed its colonial identity in their academic readings. This absence and understating of colonial history sparked discussions on historical invisibility and the need – or lack thereof – to rewrite this history. In a parallel exploration at Goldsmiths University, London, the absence of colonial traces in England’s history was just as palpable. This begs the question: is there a need to inscribe this unwritten history and reframe its historical facts? Does art and artistic research carve out a space for such re-reading? I offer a course under the title of Contemporary ar(T)chaeology and Prosopagnosia of History at Goldsmith for master students in the Fine art department. During our visit to the Maritime Museum, it became evident that colonial history played a significant role. However, we also recognised that our historical knowledge had somewhat overlooked the discourse surrounding colonialism. In this specific context, it appeared that there was a blurring of lines between colonial and metropolitan histories, as well as between the East and the West, the South and the North.

Should we even call it colonialism? Should we use the term British Aera instead? This is debatable as Nigel Kelly, the author of History and Culture of Pakistan, one of the Cambridge bard students’ textbooks, refused to read colonial endeavours of history critically. In his historical narrations, the British were there. They came for business, as the East Indian Company was a business company rather than a military colonial force. Indeed, there was some disagreement and conflict. In the next course, I encourage students to inscribe their own stories in the margins of their textbooks, crafting a narrative that, while unable to be defined as knowledge due to its absence of epistemology, provided a valuable space to navigate post-colonial discourses that often stagnate into unproductive jargon.

We call it a historical revenge. This assignment aims to examine the colonial and postcolonial sections critically and then rewrite them, adding their own insights in the margins. Their writing stemmed from their personal connection to the books, integrating their narratives and how they perceived the colonial history of India and subsequent postcolonial nationalism. Here, the practice aims to connect the broader historical perspectives to meet individual narratives, emphasising the significance of both macro and micro narrations. Marginalia has been the foundation of the dialogical system of disseminating a manuscript. In A manuscript-based culture, commentaries and glosses begin as notes literally written in the margins of the original work. When the work is copied, these may be incorporated into the main manuscript, creating a new book with additional, original content. This process can continue as long as anyone is interested in the book. A book manuscript is a wiki, while a print edition is simply a text. The failure to comprehend this distinction is an essential cause of the undervaluation of Islamicate[4] science. Marginalia helps us, me and my students, practice provocativeness and playfulness simultaneously, which holds a powerful decolonial potential by enabling readers to challenge dominant narratives, question authority, and reclaim marginalised perspectives within texts. Readers can actively engage with and reinterpret literature through marginal notes and annotations, shedding light on micro-histories and alternative worldviews that colonialism sought to erase.

This text is not a post-work reflection; rather, it’s an echo that occurs simultaneously with the act of doing. Hence, writing isn’t the final stage of the work but rather a concurrent process of expressing thoughts in words and text. The act of writing, formulating sentences, and crafting them opens up the possibility of rummaging into memory and history, exploring the relationship between myself and my students, and traversing borders. It is a glimpse into how I envision my own itinerancy and serves as an introduction to a broader journey akin to a funambulist’s. This is an ongoing process, as is the nature of any change.

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

While my educational journey extends beyond institutional practices, this essay primarily focuses on my experiences in university teaching.

2.

A tale of two universities, Fatima Khan, Mutee-ur-Rehman, Dawn Newspaper, August 13, 2023.

3.

The life of an itinirant

4.

Coined by Marshall Hodgson in the mid-60s, the term “Islamicate” refers to the moral values and cultural forms that disseminated throughout the global system of Muslim trade and influence during the centuries following the emergence of Islamic polities but not necessarily related to Islamic faith.

PhD is an artist, writer, educator, playground maker, and necromancer. His research-based practice includes films, installations, and archival studies. His works investigate histories from The Global South, labour and the means of production, and histories of political relationships that have existed as a counter narration to the east-west, North-South dichotomy. By bringing multiple subjects into his study, he explores possible correspondences seen through the lenses of contemporary art practice, proletarianism, subalternity, and the technology of image production. His works emphasise films and historical materials to bring questions such as what happens when the narration crosses the border and what the future of our collective past is. In his practice, he reflects upon the marginalia of artistic explorations in relation to art, the history of transnationalism, and global politics. Khosravi Noori is a member of the editorial board of VIS Journal for Nordic Artistic Research and co-founder of Sarazad.art