Pedagogies of Remembrance: Collectively resisting the violence of forgetting

Alessandra Fudoli

CATEGORY

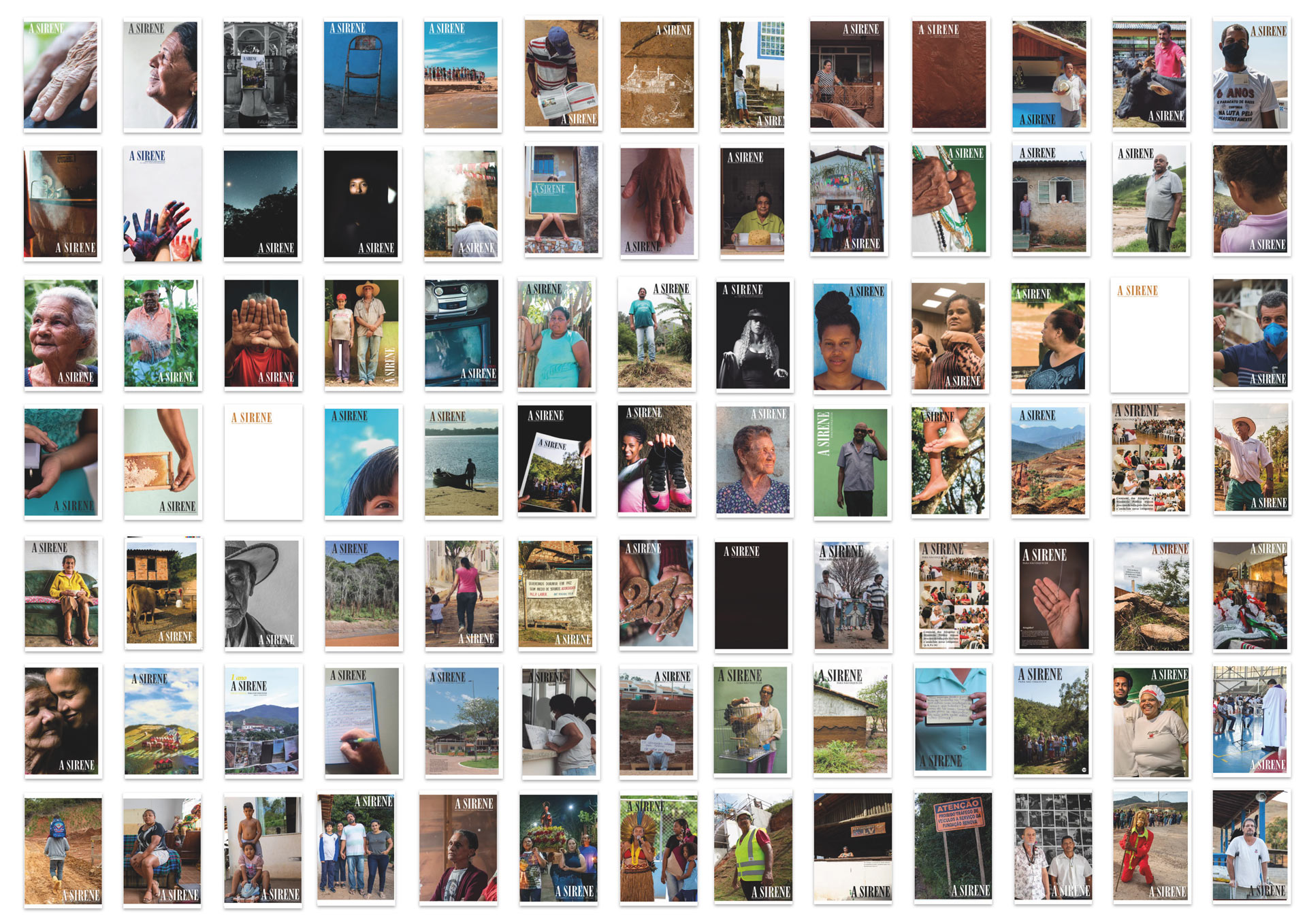

From the haunting afternoon when a tailing dam ruptured in Mariana in 2015, the question “Who was your siren?” reverberated through a newspaper born from the loss of the affected community, reflecting upon the lack of protection mechanisms and attempting to build a collective memory of the violence suffered.[1] Alternative museums and archives as this one claim attention to the act of remembering difficult memories as an urgent pedagogy.

As architects and urban designers, we often rely on digital libraries of materials while doing collages and renders. But where do these materials we choose come from? And how does the process of extraction and production of these materials reflect in our cities? I believe that both professions are not restricted to the construction of new buildings and urban fabrics, but also require a study of the whole process and the resources involved in construction, as well as their impacts. With this in mind, I conducted an investigation about landscapes associated with iron mining in Brazil, and how their connection with global logistics not only impacts, but leads to responses to be learned from local agents.

Folder with different iron textures used for architectural models.

The first story I want to share begins in 1910, in Stockholm. During an international congress, Brazilian researchers presented a map accounting for 10 billion tons of iron ore deposits in Minas Gerais.[2] One year later, the announcement triggered a race by foreign companies to set up operations in the region’s so-called Iron Quadrangle. In 1942, the activity intensified in Itabira and, in the context of the Second World War, the city was incorporated as part of the Washington Agreement with the goal of supplying iron to the war industry. While the North American government created infrastructures, it was up to the mountain of Itabira to deliver 1.5 million tons of iron per year at low prices until the end of the war.[3] This moment marked the birth of Vale, a major Brazilian iron ore company, and the consolidation of the country’s first iron ore mining complex. In a few years, the mountain, so symbolic to the poet Carlos Drummond, was pulverized until it reached a condition of inversion.

The 1980s witnessed a confluence of factors at the national and global level, driven by Chinese economic reforms, demands for new infrastructures, and the subsequent commodities boom. These phenomena precipitated the premature expansion of small Brazilian cities.[4] As a consequence, the accelerated pace of what was understood as progress, dictated by global capital, mobilised resources but failed to translate its benefits into improvements in the lives of local actors. Instead, it obscured the unique rhythms of these communities, rendering them invisible within the whirlwind of development.

As Vale expanded, its shares became some of the most traded on the New York Stock Exchange in 2007, and it received substantial national funding of approximately $1.3 billion, based on current exchange rates.[5] One year later, Vale was responsible for Brazil’s biggest environmental crime. The city of Mariana, located close to Itabira, suffered extensive damage due to the use of a risky method for the construction of a dam, which was also more economical. Besides several deaths and injured people, the resulting mud traveled 680 km until it reached the ocean. Bento Rodrigues, a subdistrict of Mariana, had 80% of its buildings destroyed.[6] With the purpose of preventing further destruction, Mariana was quickly listed as a heritage landscape. The fast pace of the act, however, resulted in the lack of a precise definition of the object of preservation and its guidelines.[7] As a consequence, the government gathered efforts with ICOMOS and regional universities, and promoted meetings with the community.

In the aftermath of the event, the affected agents found the strength to mobilize resources and promote alternatives to value their ways of life and memories, reinforcing support networks. Among these flourishing narratives, the proposal of a Museu Território (Territory Museum) aimed at acknowledging the plural collective memories that inhabited the city, especially by fostering a dialogue about the community’s difficult memory, and raising awareness at a national level about the event whose significance transcended the city limits. Its final goal was to become an instrument for building local capacity, development and, ultimately, resilience. It was envisioned as a living organism, constantly evolving and not dependent on a fixed building — as traditional museums. Through focus groups, the residents expressed their desire that the memory of the destruction remains alive through the preservation of ruins, the creation of marks to indicate the level the mud reached in buildings, the name of the former inhabitants, the replanting of typical trees from their childhood, and also the construction of a memorial.[8] In this case, the reconstruction of the site would mean the erasure of their memory.

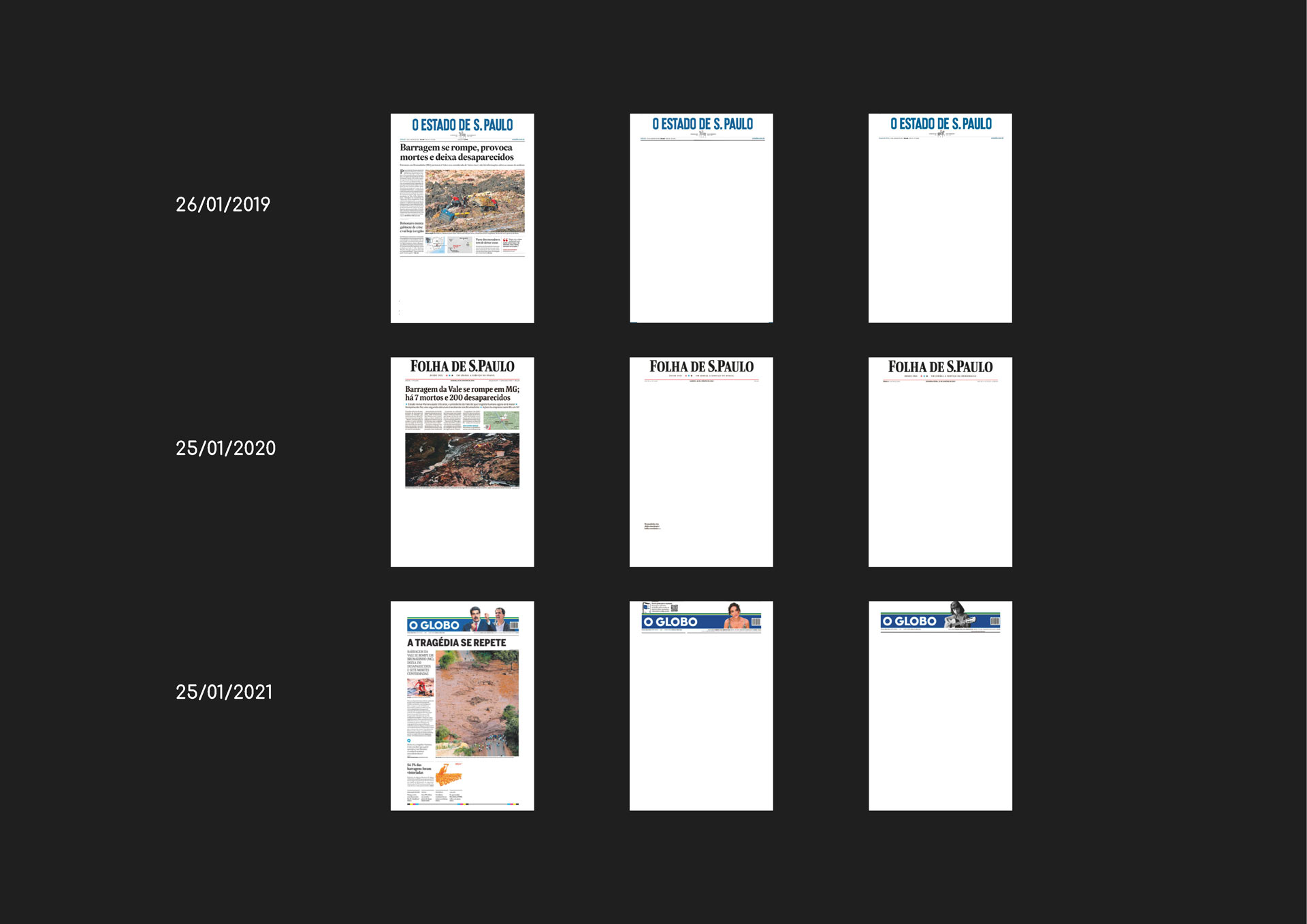

When referring to memorials, places or objects that contribute to preserving and disseminating a memory, the German language makes a distinction between the words Denkmal and Mahnmal. While the former is related to the etymology of “monument” and comes from the Latin verb monere or “to remember” the latter expresses the urge to actively recall a difficult memory that should not be repeated.[9] For instance, in Berlin, Mahnmal is used as the title for the Holocaust Memorial. In Brazil, the creation of a memorial site for the difficult memory of the Mariana disaster would help contest the erasure caused by the mud and engage in a dialogue against further disasters. The repetition of a similar event only four years later in the city of Brumadinho reflects the need for more dialogue. Despite manifestations, such as a march in the opposite direction of the mud carried by 300 people one year after the Mariana disaster, the absence of articles about the events in the main newspapers reinforces the need for such pedagogical spaces.

Headlines from the main Brazilian newspapers (Estadão, O Globo, and Folha de São Paulo) with excerpts from the texts that mention the Brumadinho disaster on the day after the event and in the following years.

The dialogue was extended by the affected people, who felt the need to shift from being interviewed to being the protagonists of their narratives. Thus, through self-organisation and funding from donations, they founded their own vehicle for denouncing their realities and building a collective memory: a newspaper named A Sirene. They took the role of researchers, photographers, and narrators of their own stories, identifying issues and proposing solutions. As a result, a public archive was created, which resonates not only within their community but also with numerous others residing in proximity to mining sites, contributing to enhancing a shared identity and fostering an ongoing dialogue. Beyond its local impact, the newspaper serves as a resounding voice for these diversely affected communities, amplifying their voices on a broader scale. In conclusion, both the newspaper and the museum are a method to be learned by other vulnerable communities to bridge the gap between the lack of spaces to share their voices — either in hegemonic institutions or established forms of research — and the urge to address the conflicts that arise from their proximity to the mining sites.

Covers of the newspaper A Sirene.

Other practices in the country have been concerned with creating alternative pedagogies that raise the voice of marginalised agents and their fight against the erasure of the violence they endured — as well as against the repetition of the events. One outstanding case is the Museu da Maré (Maré Museum) in Rio de Janeiro. Located between major roads, the airport and Guanabara Bay, the Maré neighbourhood can be characterized as a slum and is home to around 140,000 people concentrated in about 4km². Since 1997, residents have been gathering together through an NGO called CEASM (Maré Study and Solidarity Action Centre), aiming to transform the stigmatising gaze of the slum, enhancing the population’s right to the city and their collective memory.[10]

The group’s first project was the Rede de Memória da Maré (Maré Memory Network), which instituted an archive with texts about the history of the neighbourhood, photographs, maps, and other items donated by residents. After applying to national calls for proposals, the project became a museum in 2006, with an exhibition organized through 12 “Times.” While the Time of Water, Home, Migration, Work, Celebrations, Market, Faith, Childhood and Everyday Life sections use mainly material culture as a strategy to build and raise awareness of the slum imaginary, the final three parts, Time of Fear, Resistance and Future, are strongly connected to their struggle to reshape the territory through awareness. They address the fear of precariousness, violence and oblivion, the Resistance against these conditions, and allow temporary exhibitions to reveal paths to possible futures. Nevertheless, in 2016 due to the World Championship and Olympics, the slum was hidden from the sight of curious visitors crossing the city to attend the events. Opaque acoustic panels were installed by the municipality around the area, together with a special paramilitary police.[11]

The policy of masking the city’s precariousness with great urban renovations and new constructions, together with real estate speculation, led to the eviction of around 70,000 people between 2009 and 2015. In Vila Autódromo, where there was a slum derived from an old fishing village from the 1960s, all that is left are the ruins and rubble of the old buildings. This symbolic void has been documented as part of the archive of what is called the Museu das Remoções (Evictions Museum), and signs have been installed to indicate where the streets and houses of the former residents used to be. Today, the museum and its digital platform have expanded into an archive that includes the history of other evicted slums in the city, and aims to be an instrument for the resistance movement by promoting research and several events, such as debates and theatres. The main goal is to be a source of reflection on the violence suffered by these neglected communities and to prevent the perpetuation of arbitrary evictions.

Amid the violence arising from the fast pace of capital and what is called progress, the emergence of alternative museums and archives stands as a testament to the resilience of affected communities. More than that, the proposals are potential pedagogies that evoke the word Mahnmal, promoting active remembrance to help prevent the recurrence of such violence. The memorials are an attempt to project a future in which they would no longer need to be built, as the existing ones would be capable of shaping a strong collective memory — translated into collective consciousness — able to prevent the same events from happening again, and to symbolically reconstruct the places that have been destroyed.

The active role of the communities described highlights the fact that memory is not merely a passive recollection, but a powerful tool for transforming their realities: besides reflecting on their collective identity and stressing injustices, the spaces aim to imagine future paths. Given that learning is central to creating tools to face urgent current and future social challenges, emphasising these examples of alternative forms of producing and sharing knowledge is a powerful tool to be used in conflicting territories beyond the proximity of mining sites or the ones marked by forced evictions. The alternative methodologies can be learned and adapted to other contested territories, empowering learners to become actors, and promoting emancipative forms of action, care, and resistance.

Finally, we architects and urban planners have a lot to learn by listening to the voices of these marginalised communities. For instance, by reading their newspapers and visiting their museums we can gain a better understanding of how certain materials we use impact our cities, and therefore design strategies to avoid damages as the ones of Mariana and Brumadinho. As we witness an increased demand for minerals such as copper and lithium, driven by an energy transition and often located on ancestral lands in Latin America, it becomes imperative to remember the disasters and understand how not to repeat the same violence. In addition, by acknowledging alternative methodologies proposed by the affected communities themselves, such as the archives of shared experiences of violence of the Museu Território, Museu da Maré, and Museu das Remoções, we can help to co-design and promote spaces that amplify their voices, expose their collective memories and foster their desired futures.

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

Jornal A Sirene (2016). Ed. 0 (fevereiro). Issuu, 5.

2.

Wisnik, J. (2018). Maquinação do mundo. Companhia das Letras, 38.

3.

Ibid., 106.

4.

Cardoso, A. & Melo, A. (2016). O papel da grande mineração e sua interação com a dinâmica urbana em uma região de fronteira na Amazônia. Nova Economia, v.26, 1239.

5.

Ibid.,1220.

6.

Castriota, L. (2019). Dossiê de Tombamento de Bento Rodrigues. ICOMOS-BRASIL, IEDS & PPACPS, 12.

7.

Ibid., 13.

8.

Ibid., 271.

9.

Ibid., 273.

10.

Rose, C. (2019). Museu da Maré: Museologia a partir da Favela. Exporvisões, 2.

11.

Ferreira, A. (2016). Muro que separa Linha Vermelha de favela ganha painéis da Olimpíada. G1.

is an architect who graduated in Architecture and Urbanism from the University of São Paulo (2021) and is now concluding an MSc at the IUAV. Her investigations began when she carried out research with Tipografia Paulistana, underlining the value of graphic design as part of São Paulo’s memory. Through her studies in Heritage at TU Delft (2019) and with the group Demonumenta, which unfolds heritage in Brazil through decoloniality, she seeks to further explore the theme of memory. Moreover, she deepened her knowledge of Urban Studies with the PC3 group, and through methodologies encountered in her studies at ETH Zurich (2020). Her professional experience began in Portugal at Merooficina (2020) and the French studio CoBe Architecture et Paysage (2020-2021). Later, she joined the research team in the Netherlands at Het Nieuwe Instituut (2021), collaborated with the Venice Biennale (2023), and is currently engaged with ECC Italy.