Learnings/Unlearnings: Performing the Archive

Anne Pind, Amy Brookes, Fiona MacDonald, Kieran Mahon, David Roberts,Camilla Carlsson, Sol Pérez-Martinéz, Henrika Ylirisku

CATEGORY

Welcome to Learnings/Unlearnings Reader #1: Performing the Archive, guest edited by Sara Brolund de Carvalho and Meike Schalk. The reader includes contributions from the section “Embedding Environmental Learning Histories” from the conference Learnings /Unlearnings: Environmental Pedagogies, Play, Policies, and Spatial Design, which took place in Stockholm in autumn 2024. Drawing from the realms of architecture, craft, design, art- and play pedagogies, Reader #1 addresses historical case studies, art works, and historiographic insights, providing a critical lens from which to view contemporary practices within the field.

Various histories and historiographies of learning have focused on play, emancipation, civic action, and their spaces, often seeing their material and institutional manifestations, as well as performances and experiences of learning, as entangled. This Reader reflects upon archival sources, and overlooked or forgotten histories of civic environmental learning and engagement, with contributors asking what impact these histories have on pedagogical practices and environments today?

The Reader’s contributions are organized chronologically, offering insight into specific pedagogical approaches and educational programmes. Starting with Anne Pind’s artistic exploration of Fogelstadgruppen (the Fogelstad group) and their Citizen School for Women founded 1925 (after women gained the right to vote in Sweden in 1919), which connects environmental care with suffrage, and the desire for education. Her text underscores the importance of diverse narratives and experiences in creating a fabric of civic engagement and transformative learning, while departing from her personal experience of repressive pedagogy. Pind contrasts the restrictive nature of traditional schooling with the innovative and supportive approach taken at Fogelstad, influenced by Swedish first wave feminism, which emphasized collective learning and personal storytelling. Her visual and literary work references the artist Åsa Elzén’s archival project focusing on Fogelstadgruppen’s relationship to earth, ground, and fallow knowledge (2019-2021).

The second contribution by Amy Brookes, Fiona MacDonald, Kieran Mahon, and David Roberts continues with the study of an open-air school building and school typologies from 1925 in the UK, including participatory archival research with children exploring their own school’s architecture. The building today houses a primary school for Muslim pupils. The pedagogical aim of the workshop with the children was to raise awareness of the plurality of our built environments throughout history, of different geographies always in relation to their local actors, and to bring this knowledge to design education and practice into the here and now. References to other school building types all over the world served as examples for designing and building 1:1 spatial situations. The group draws on Ahmed Ansari’s approach of “Decolonization of Design,” arguing that one can reach back to historical understandings of past being and their changed nature in the present to recover essential ontological features that would point to a new futural state (2018).

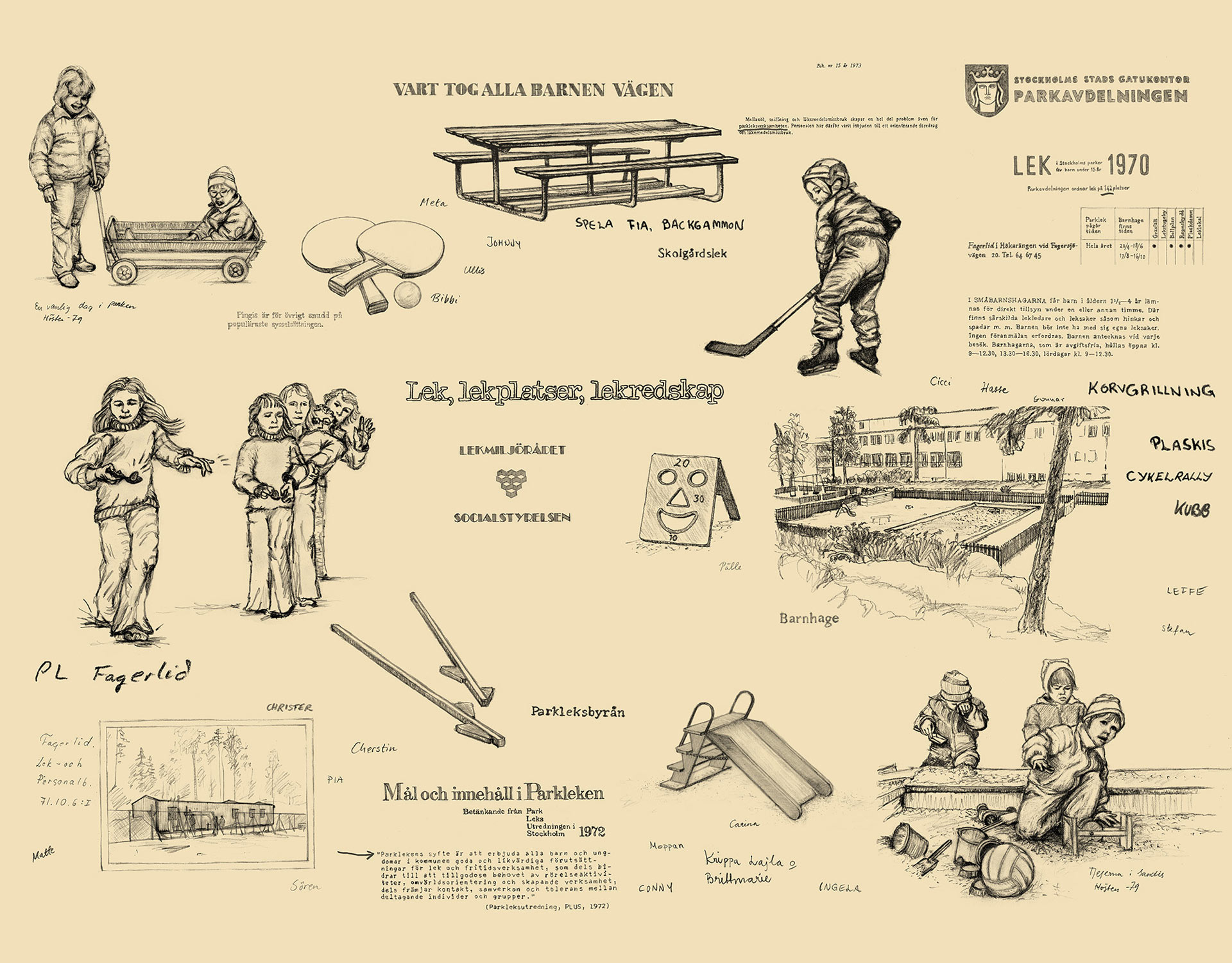

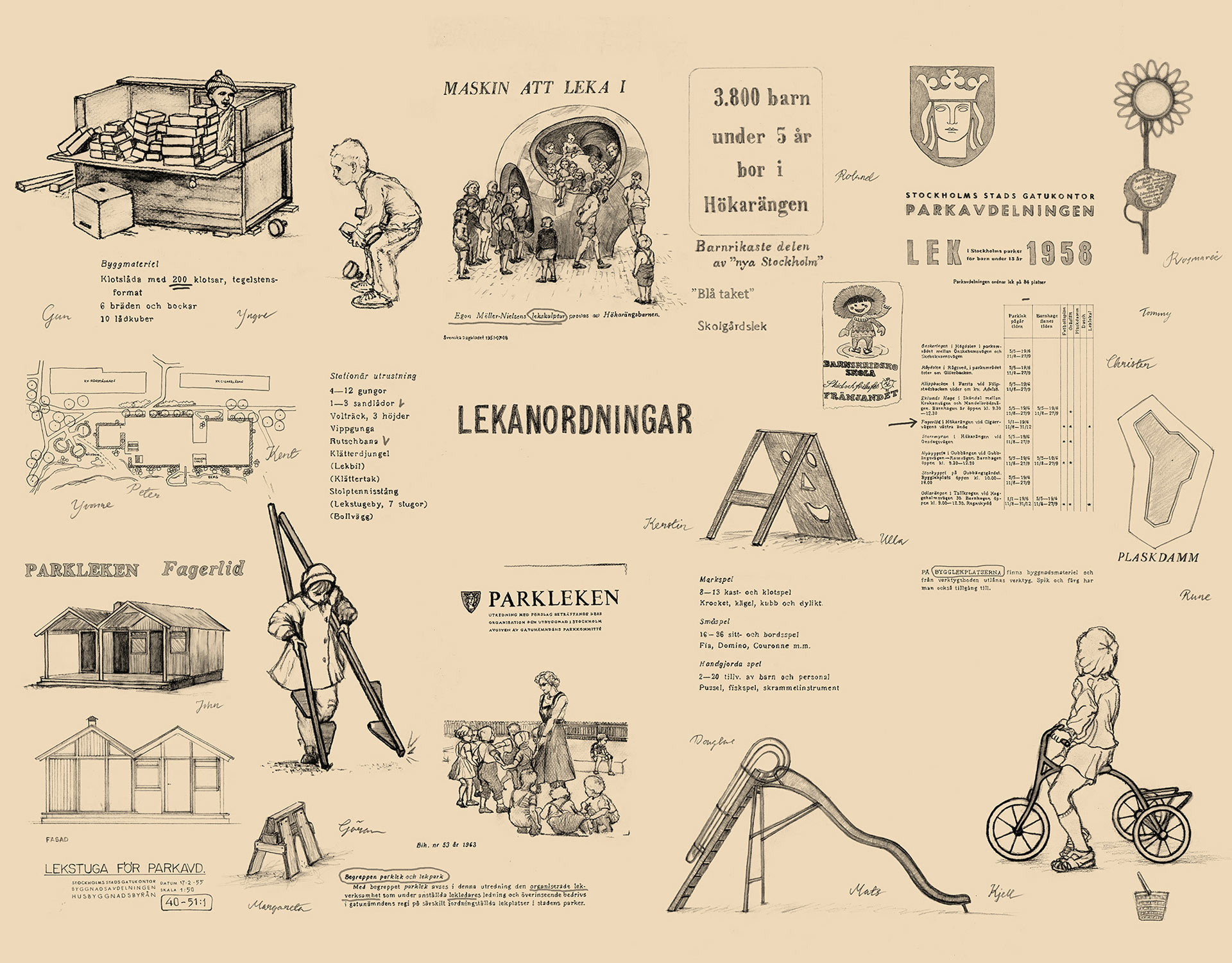

Camilla Carlsson’s contribution looks at the transformation of play spaces, with particular focus on the Parklek (park-play) format in Sweden, from 1940 to 2020. The movements’ historical underpinnings extend beyond this period, with the appearance of specific experimental outdoor learning environments like Denmark’s Skrammellegeplads (junk-playground), which encouraged children to engage in 1:1 scale building activity. Parklek, Sweden’s staffed playgrounds, emerged as a place-based pedagogy in the beginning of the twentieth century, and from today’s perspective can be viewed as a format that was firmly embedded in the structures of the Nordic welfare state. Camilla Carlsson, who is an artist with long-standing experience working with children, writes of the importance of play environments in urban settings, emphasizing the value of play for people of all ages, and connecting it to artistic processes and imaginations. Her artwork Layers of Play constitutes an archive which captures five decades of the history of the Fagerlid Parklek, a local play environment in Hökarängen, Stockholm, and foregrounds its significance for the neighborhood even today.

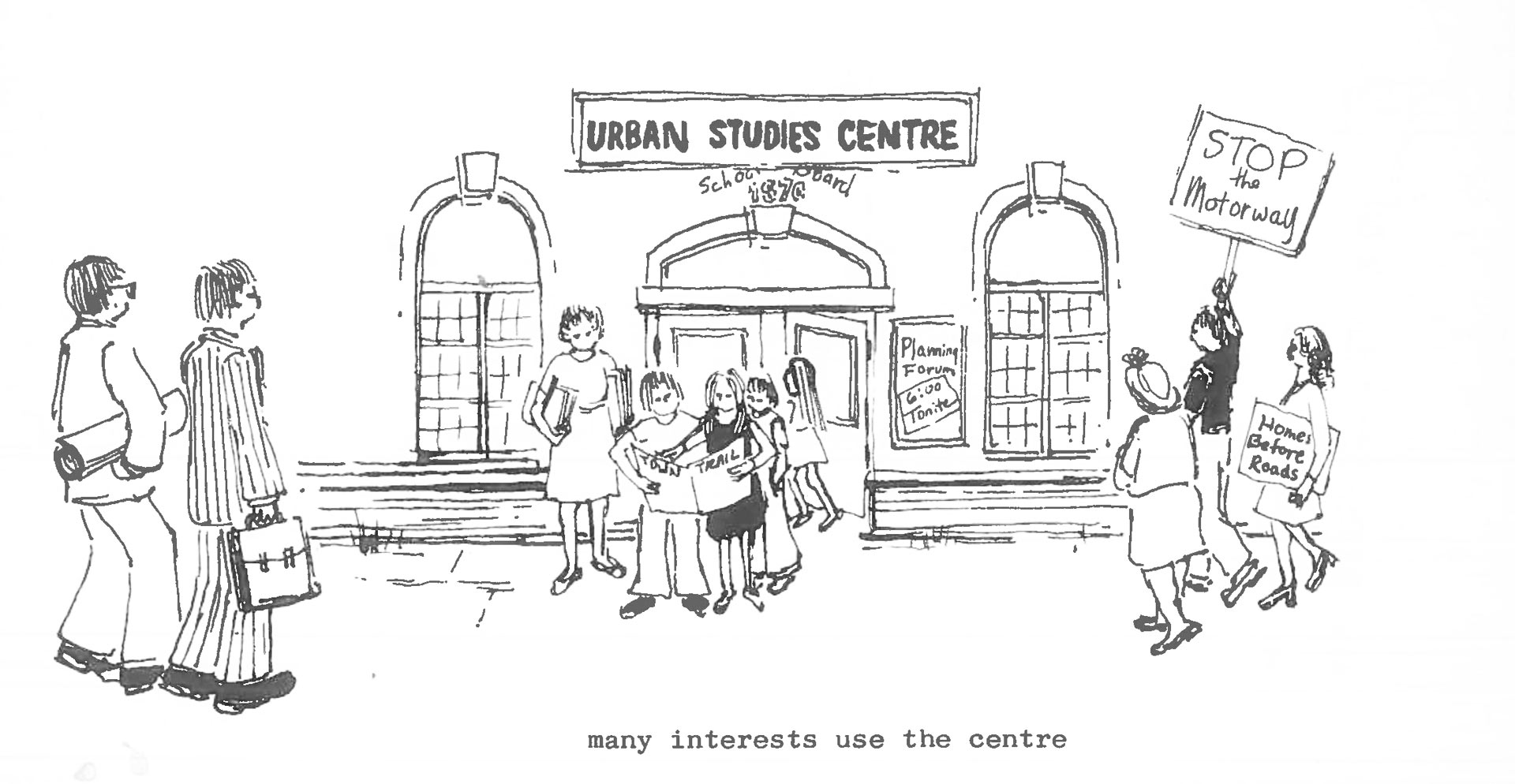

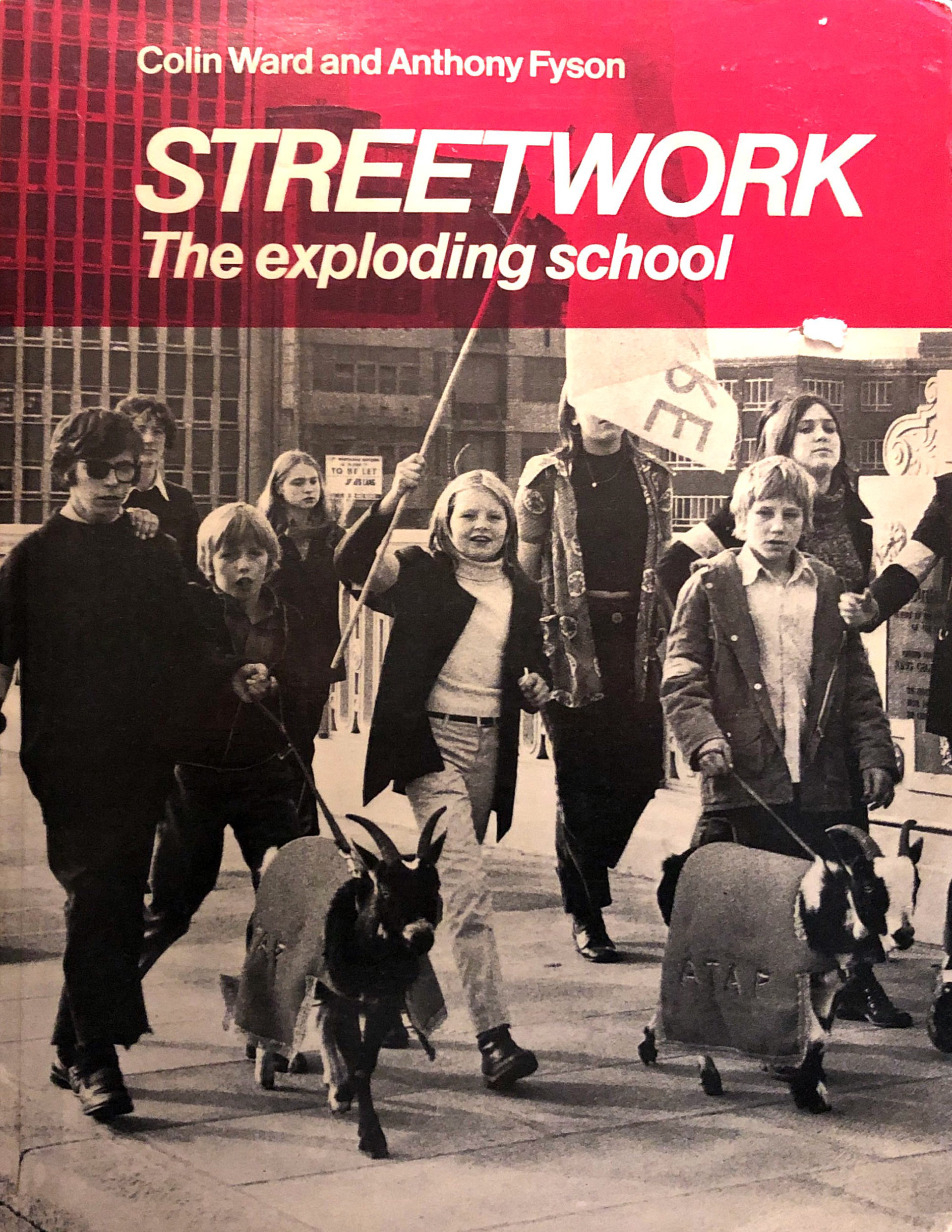

Educational architectures received increased attention during the 1960s and 1970s—a phenomenon art historian and curator Tom Holert described with the term Education Shock, in his exhibition at Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin (2021), where politics and policy measures to democratize education and its expected societal effects were widely debated. Holert’s exhibition forms an archive of “past futures, unfinished projects, abandoned experiments and forgotten but hugely impactful educational reforms” (Holert 2021, 10). The following contributions take recourse to political and pedagogical designs and counter-designs that sprung from the global atmosphere of departure during these years. They explore environmental learning as a public education and art pedagogy that formed during the 1960s, attributed to the design educator Ken Baynes, art educator Eileen Adams, and the social historian and anarchist writer Colin Ward in Britain. Sol Pérez Martínez’ historical research takes us to the UK between 1968–88, and the grassroot organization Urban Studies Centres (USCs), initially advocated by Ward and the planning journalist Anthony Fryson. USCs formed a network for public education and citizen involvement in architecture and planning that sought to empower citizens to influence their surrounding environments. Pérez Martínez uses the term “Situated Pedagogies” to describe the approach adopted by these organizations, combining considerations for the environment, education and equity, and highlighting the pedagogy and collaborations behind the goal of increased civic engagement.

Finland witnessed the development of a robust culture of art-based environmental education from the 1960s that survived periods when culture, education, and social projects experienced severe funding cuts in other parts of the world. Finland even established Environmental Education (EE) and Sustainable Development Education (SDE) in their national school curricula in 2003. In the fifth contribution Henrika Ylirisku maps the tradition of environmental art education from its formation in Finland in the 1960s until today. A school reform in the 1970s made art the first subject to integrate environmental education as one of the core content areas in Finland. Her paper takes us from a socially conscious and culturally critical approach, to a shift toward art pedagogies emphasizing personal aesthetic experience and environmental sensitivity in the 1980s, and finally to a diversification into various parallel strands since the 1990s that also embrace an emphasis on promoting social justice and societal activism as integral parts of art education. Recent initiatives include feminist, posthumanist, and new materialist theories to decenter human exceptionalism and question binaries between nature and culture.

All papers in this Reader handle history as a resource for future educational design.

References:

Ansari, Ahmed. 2018. “What a Decolonisation of Design Involves: Two Programmes for Emancipation,” conference paper in Beyond Change: Questioning the Role of Design in Times of Global Transformations. Swiss Design Network Research Summit, March 8-10, 2018, FHNW Academy of Art and Design Basel.

Elzén, Åsa. Notes on a Fallow – The Fogelstad Group and Earth, 2019-2021. https://www.asaelzen.com/home/news.html.

Holert, Tom. 2021. Politics of Learning, Politics of Space: Architecture and the Educational Shock of the 1960s and 1970s. de Gruyter.

Contents

Citizens of the Fallow: The Unintended Ground of the Women’s Citizens School at Fogelstad. The Where of the We Matters: Seven Threads

Anne Pind

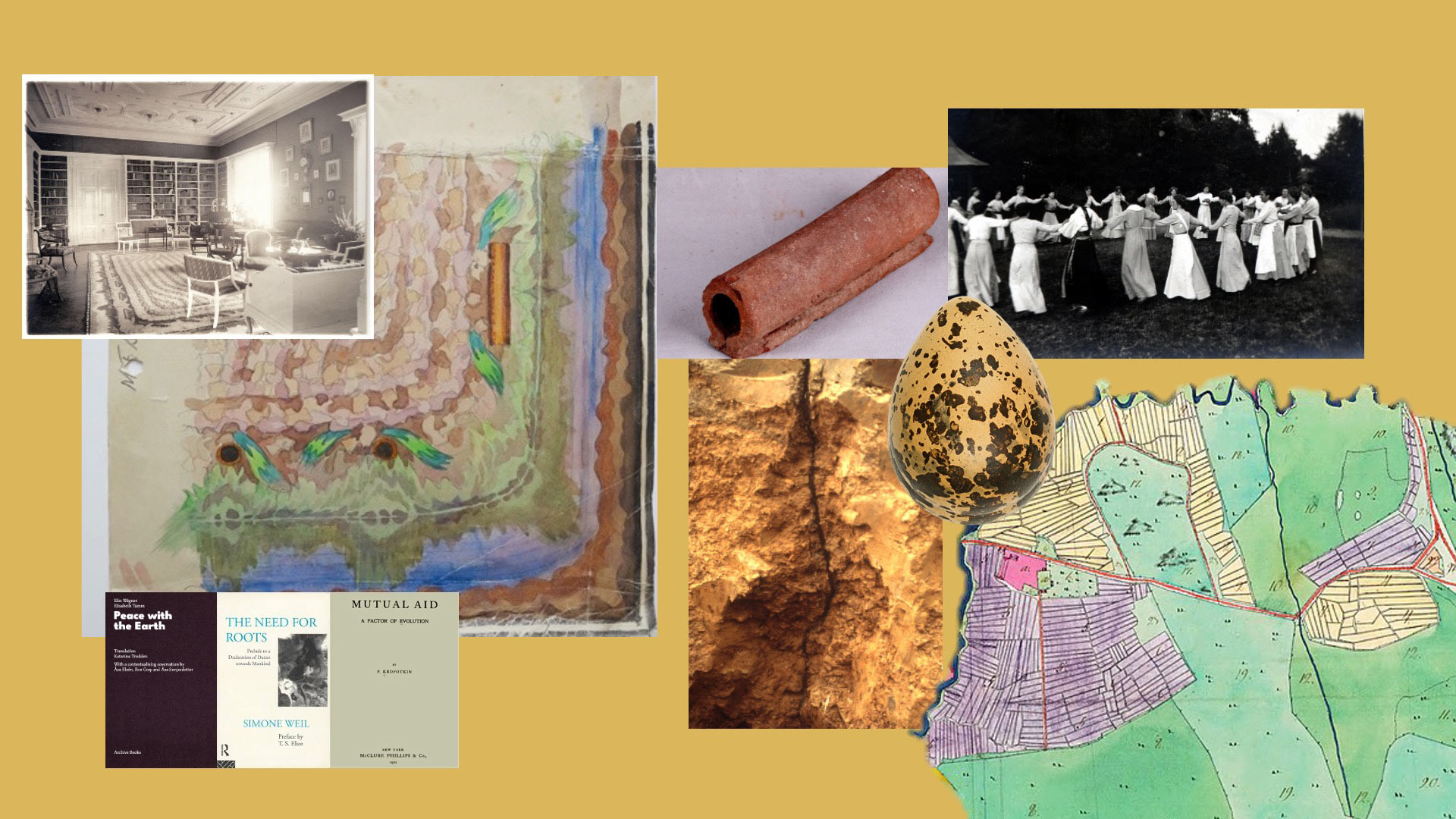

Citizens of the Fallow. Collage by Anne Pind. The collage assembles the following material: Fallow tapestry carpet in the library at Fogelstad, (Photo: Fotoateljén H. Cederin, Katrineholm. Reproduction: KvinnSam, Gothenburg University Library), A Fallow, water colour sketch by Maja Fjaestad 1919, part of A Growing Fallow Archive, within Notes on a Fallow – The Fogelstad Group and Earth, ongoing work, Åsa Elzén, 2019– (Photo: Åsa Elzén, 2019), cover ditch brick pipe (Photo: Wikimedia Commons), circle dancing on grass at Fogelstad (Photo: Unknown. Reproduction: KvinnSam, Gothenburg University Library), earthworm burrow, egg of a fallow bird, field division patterns at Fogelstad 1795, (Images: Wikimedia Commons), Book covers: Elin Wäger and Elisabet Tamm: Peace with the Earth, 2021, Simone Weil: The Need for Roots, 1995, Peter Kropotkin: Mutual Aid, 1902.

The first school I attended in the 1980s in Denmark was a so called “free school,” meaning that the school (in some ways) was freed from following the protocols of the state school system. We did not have books—we made our own—and learning was not confined to a classroom or curriculum. School felt more like a village, happening organically here and there.

Then, my family moved, and I was enrolled in a new school. Here, we had to stand in line silently in the hallway and wait for the teacher to unlock the classroom. And here, learning was something scheduled, subject-named, competitive, and sometimes violent, as teachers would occasionally hit us with pointers. Even though such punishment was formally forbidden, a culture of fear persisted within the school grounds. What I had learned so far—building a mud house in a group and cooking pancakes on hot rocks—had no value here. What mattered was finishing your assignment first, and foremost.

We stayed in this town for two years, but it has taken many more to unlearn the fear of buildings called “schools,” to regain trust in teachers, and become curious in classrooms. In other words, to say something aloud, even if it is not the answer.

Raising your voice among others, sharing and listening to personal stories, taking risks collectively, playfully, and learning to fail without fear of exclusion, are just some of the things I have absorbed from studying the pedagogical spaces and practices of the Women’s Citizens School at Fogelstad in Sweden.

The school was founded in 1925 by Ada Nilsson, Elisabeth Tamm, Elin Wägner, Kerstin Hesselgren, and Honorine Hermelin, who met criss-crossingly when the suffrage movement struggled to secure women’s legal right to vote in Sweden. As a group they were jointly and diversely committed to questions of peace, social care, land ownership, experimental pedagogy, organic farming, and sexual politics. Some of them were part of international networks for peace, some travelled abroad to study composting techniques, and all of them nurtured lifelong kinships in the outskirts of normative family structures.

With a textile metaphor, Ada Nilsson describes the group’s constellation as an open-ended weave, ready to include and be altered by others, “Through unforeseen fates and circumstances, . . . they have met—and something has happened. They are no longer the same after their meeting, and they draw others into their constellation. It becomes a fabric of life with all its various elements.” (Nilsson, 1956, 13)

I read this intricate “fabric of life” in which threads meet and impede each other, as the ongoing collective work of weaving a common ground for political action and thinking, a space in and of learnings.

The Women’s Citizens School at Fogelstad held its first course in 1925 and its last in 1954. The school did not receive any state funding but relied on private donations and was free to grow an experimental learning environment and curriculum of its own.

On the day of the school’s inauguration, Elisabeth Tamm, owner of the Fogelstad estate, spoke of the need for a shift in power following women’s suffrage, insisting that power needed to be taken from the hands of the few—landowners and warlords—operating in alliances of social and environmental destruction. She proclaimed that citizenship ought to be the foundation of society, not capitalism, anticipating the many ways in which women’s experiences would come to alter political decision-making and policies. (Tamm 1925, 2) Fogelstad would offer women a space of transition: Somewhere to gather and collectively unlearn the lessons of patriarchy; somewhere to mend alliances of trust and solidarity across differences in privilege and position; somewhere to discover the transformative potential of what citizenship could be.

Teaching methods developed through interaction and participation; in political role-play, choir singing, lecture-question sessions, and home-stead nights for sharing life experiences. “Everyone has a story to tell,” was headmistress of the school, Honorine Hermelin’s ethos for collective learning. (Blomberg, 1956, 142)

Honorine Hermelin contemplates in writing how the “secretive power” schools hold over students too often goes unnoticed and that a “school of free thought,” as Fogelstad hoped to become, must rest on what she calls “unintended ground.” (Hermelin, 1956, 203)

Ground-thinker, and philosopher Simone Weil formulated her attempt to practice an ethics of attention, (l’attention,) as a way of de-centering the self and meeting others without intentions of a certain outcome or result. (Weil 2009, 100) Attention manifests in friendships, kinships, in care and curiosity for the unexpected, not domination. Following Weil, we can begin to imagine a Citizen’s School on unintended ground rooted in reciprocity and political plurality; a space in which you train yourself to be open to, and opened by others.

Elsa Björkman-Goldschmidt, lecturer and course participant at Fogelstad further diversifies grounds for learning, “In most types of schools, there exists a foundational concept, a guiding principle, which manifests as an expansive, vibrantly shimmering meadow, teeming with diverse and colorful herbs.” (Björkman-Goldschmidt, 1956, 10) This vibrantly imaginative meadow is neither claimed as school property nor named as a knowledge field. It is open to all sides, abundant, and already in bloom.

Honorine Hermelin’s metaphors for building, be it knowledge, community, or school, are neither fixed nor set in stone—they are nomadic. “I always thought of Fogelstad as nothing more than a provisionary station, a tent, on the way towards women’s citizenship,” she writes, thus unbuilding “school” as a space of hierarchical order and discipline confined in one-directional classrooms. (Hermelin, 1969, 36). Instead, she offers the idea of a school-in-movement, an easily dismantled lightweight structure made from foldable and transformative materials. In this classroom, learning is not sheltered from a distant outside. School is out!

Accordingly, the Women’s Citizen School at Fogelstad did not manifest its purpose or pedagogy spatially by building anew—it moved into and improvised within the existing building ensemble at the estate, changing position over time as more participants joined their courses.

When farmer and politician Elisabeth Tamm inherited the Fogelstad estate from her father, she began making minor changes to the spatial layout of the main building, transforming the grand salon into a library, for example. Six years prior to the inauguration of the Women’s Citizens School, Tamm asked Swedish artist Maja Fjæstad to design a handcrafted carpet to be rolled out on the library floor; a fallow field tapestry. (Levin 2003; Karin Faxén Sporrong 2022, 14)

At this time, practices of fallowing were becoming marginalized by large scale industrial farmingforcing arable land to produce at high speed, and high volumes, adding chemical growth shortcuts to the soil.

In contrast, a field lying fallow makes space for unexpected growth as it upholds the livelihood of multiple societies of microbes and bacteria. As such, fallow temporalities are more than waiting for soil to be restored (as a narrowly human resource), but processes of intensification that cannot be foreseen. A fallow, undisturbed by humans’ interference, becomes a spaces of radical openness, interconnectedness, and multiplicities of movements.

The fallow carpet at Fogelstad was designed by Fjæstad and woven by her sisters-in-law into a large patch of soil newly turned by ploughing in thick curvy lines, surrounded by a lush greenish ditch, holding a body of excess water, drained from the field by cover ditch pipes immerging between the weeds. Historically, ditches have marked human ownership of land. This complex ditch space exposes human’s interference, including territorial thinking, to registers that resists utilization: The fallow carpet at Fogelstad cannot be re-cultivated, it remains in a state of imaginative openness.

Recalling Elisabeth Tamm’s words, that citizenship ought to be the foundation of society, not capitalism, I propose that the fallow tapestry carpet anticipated the unintended ground of the Women’s Citizen’s School by interlacing questions of ownership, suffrage, and maintenance, and that it thickens Weil’s ethics of attention by including the voices and world-making capacities of non-humans.

In 2019, a hundred years after the design of the fallow tapestry, Swedish artist Åsa Elzén retrieved the carpet from the attic at Fogelstad and reintroduced it as a ground for conversation: somewhere we can rediscover the transformative potential of what citizenship could be. (Åsa Elzén 2019; Åsa Elzén, Ros Gray, and Åsa Sonjasdotter 2021, 118) Who are the citizens of the fallow? That question still lingers in the field margin.

I have never opened a paper with a personal story before and I have been curious, and nervous to do so. As such, this is an (unasked for, and unanswered) experiment, a transitional paper—perhaps an opening to something unexpected.

I have learned from Fogelstad, that “everyone has a story to tell,” but one story is not enough to maintain an intergenerational “fabric of life”, we need multiple: – unlocking the classroom – weaving grounds for learning – come together! – on unintended ground – who makes a classroom? – the citizens of the fallow – everyone has a story to tell –

Will you go on?

*Note: Quotes originally written in Swedish are translated into English by the author.

References:

Björkman-Goldschmidt, Elsa, Ragna Kellgren and Elsa Svartengren, eds. 1956. Fogelstad: berättelsen om en skola. Stockholm : Norstedt.

Elzén, Åsa. 2019. ‘Notes on a Fallow – The Fogelstad Group and Earth’. A Growing Fallow Archive, (website) http://www.asaelzen.com/home/Notes_on_a_Fallow_The_Fogelstad_group_and_earth

Elzén, Åsa, Ros Gray, and Åsa Sonjasdotter. 2021. ‘Re-Reading the Pamphlet A Contextualizing Conversation’. In Peace With the Earth, by Elin Wägner and Elisabeth Tamm, ed. Åsa Sonjasdotter. Berlin: Archive Books. https://parsejournal.com/article/peace-with-the-earth/

Grönbech, Honorine Hermelin. 1969. Från Ulfåsa till Fogelstad: Samlade Fragment. Stockholm : Aronzon-Lundin: Natur o. kultur.

Levin, Hjördis. 2003. En Radikal Herrgårdsfröken: Elisabeth Tamm På Fogelstad: Liv Och Verk. Stockholm: Carlssons.

Sporrong, Karin Faxén. 2022. ‘En matta för vår tid – historien om “En träda”’. Väv, 2022.

Tamm, Elisabeth. 1925. ‘Det Verkligt Nya’. Tidevarvet, 1925, 16 edition.

Weil, Simone. 2009. Waiting for God. Harper Perennial.

Schools Without Walls

Amy Brookes, Fiona MacDonald, Kieran Mahon and David Roberts

This paper draws upon feminist and educational theorists to reflect on a week-long, architectural archive-driven, live construction and performance project. Schools Without Walls involved 30 eleven-year-old students and their teachers at Orchard Primary, London designed in the 1920s as an ‘open air’ school, now a voluntary-aided Muslim faith school. The project introduced students to their school’s radical architectural and pedagogical history and invited them to creatively interpret, build and perform their own versions of this history in a series of site-specific learning pavilions.

The first phase of the project took place in local, municipal and educational archives as we began to think about how architectural history could mobilise a socially engaged project. While reviewing artefacts related to educational architecture in early twentieth-century Britain, we were drawn to the open-air school movement and its radical fusion of architectural and educational practice. Open-air schools were designed to provide disadvantaged urban children with fresh air, good ventilation, and exposure to the outside to alleviate poor health and combat the rise of tuberculosis.

This archival research helped us identify Orchard Primary School in Lambeth designed by the London County Council which opened in 1925. Four square pavilions act as the school’s classrooms with exposed roofs and timber half-walls whose windows remained unglazed until the 1950s.[1] The school grounds of this former orchard were equally important to a curriculum both experimental and needlessly gendered in which boys drew chalk world maps on walls for geography and constructed bird tables while girls undertook nature study and handicrafts. “Although our classrooms are open-sided shelters which cannot be closed,” the school’s first headteacher I.G. Jones explained, “it is much pleasanter to work in the open-air without a roof overhead whenever possible.”[2] This was a vison of schooling described by John Boughton as catering “for the wellness and wholeness of its students” but we noticed a conspicuous absence in the archives – where were the voices of these students for whom this educational space was being designed?[3] The documents were dominated by the words of educators, architects or policy makers. How, then, could our participatory project offer a way to address such gaps, both in method and in concept?

We developed learning materials and activities in dialogue with Orchard Primary’s teachers who shared with us their enthusiasm for the school’s unique architectural history as well as their commitment to diversifying the history curriculum to be more representative of the school’s cohort of young Muslim students of colour of whom 95% have English as an additional language. Jane Rendell explains how social location affects “not only what but how we know,” urging attentiveness to the material, political, and emotional qualities of subjectivity and position with respect to practice.[4] As UK built environment practitioners, we reflected critically on our positionality in this collaboration, following D Soyini Madison “acknowledg[ing] our own power, privilege, and biases” at a time of rising Islamophobia, inequalities and injustices, and diminishing government support for design teaching.[5]

We sought to support the school’s transformative work in decolonising curricula and disciplines by attending to Ahmed Ansari’s call to develop collaborative, hybrid, derivative, and syncretic practices and discourses that enact design change within students’ own learning environments.[6] We approached the school not with a set of fixed outcomes but a methodology to displace traditional hierarchies of expertise through activities that decentre and depower alongside fostering compassion and collaboration.[7]

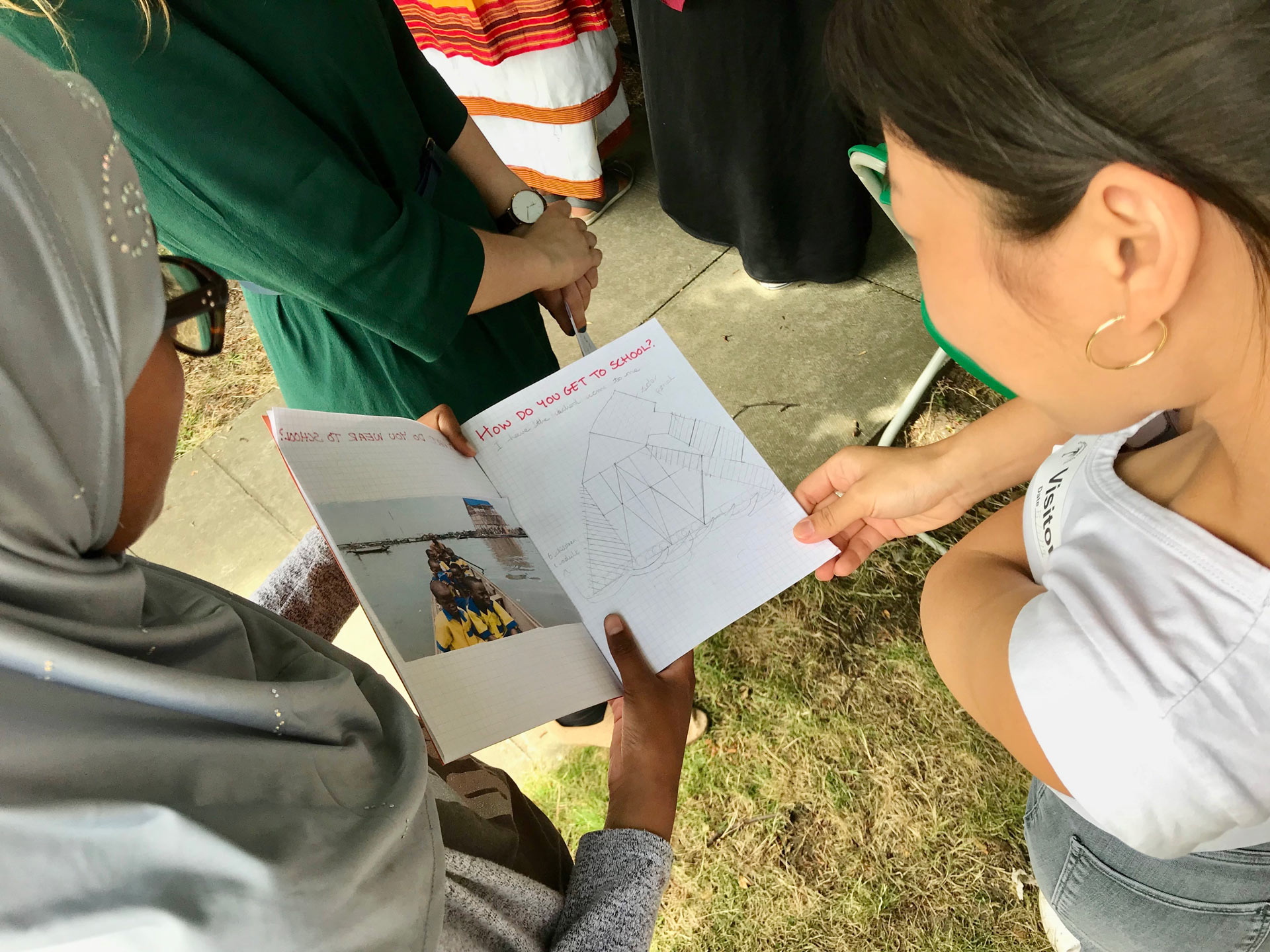

Design Exercise Book, Orchard Primary, Lambeth. Photo: David Roberts

On our first day of delivery we divided the students into groups, each of which was allocated a historical or contemporary open-air school from around the world to learn about. The precedents included: a forest school in early twentieth-century Germany; a village college in 1930s England; an open air school in 1930s France; a Montessori Kindergarten in present-day Japan; and a floating school in present-day Nigeria.[8]

Every student was given a pre-prepared exercise book, along with learning materials to read, explore, cut out, and insert alongside their more personal reflections. Prompts in the exercise books invited them to imagine themselves either as learners, teachers or architects at their precedent school. Students engaged in short creative writing and drawing exercises to take on a character, making it personal and relational as they shifted between scales, histories, geographies and perspectives. Through this, students began to connect with the diverse experiences that learning environments have offered young people across time and place, and were able to compare the precedent architecture with their own school buildings.

To share their knowledge, the groups devised short performances about their schools: narrating a day in the life; embodying their school in choreographed movement; or describing its layout. We found that as we reflected positively about the unique historical qualities of their school, students too reflected positively on their own experiences and memories of being at Orchard. As they began to articulate multiple meanings of school architecture, our project began to not only offer a way to draw from students’ knowledges, but also to witness how they interact socially and spatially on site. Colin Ward argues environmental learning in this respect not only has the capacity to empower young people but also aids adults in seeing the world anew through their eyes, something which has significant implications for making built environment practices more inclusive.[9]

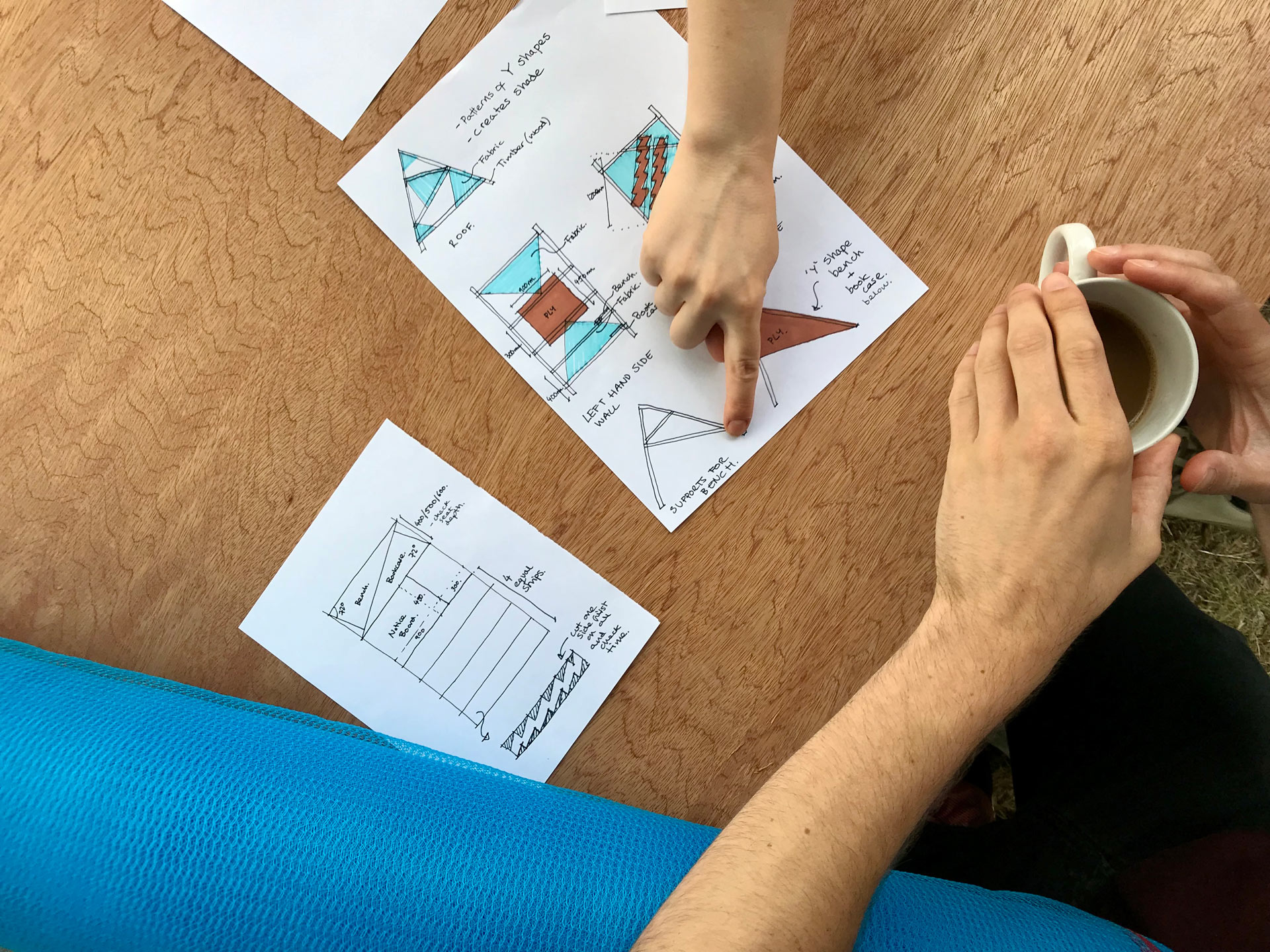

Group Model Making Discussions, Orchard Primary, Lambeth. Photo: David Roberts

As we moved into the making stage of the project we guided students through drawing, model-making and co-build activities to construct full-size pavilion structures, which made manifest how young people understand and create space. The design process built on students’ understandings of the precedent schools. Each group modelled a day at the school, inferring and interpolating from archive material, and using empathetic imagination to extrapolate from limited information. The groups were subsequently rearranged and each student became responsible for describing their precedent to their peers, becoming expert and envoy. Through these acts of thinking, drawing and making, students considered how built space influences behaviour, establishing the premises for possibility.

We made drawings and scale models of proposals for their own school, taping out the designs at 1:1 in response to specific sites. Students reflected on moments they appreciated and experiences which might be improved, utilising the precedents as common points of reference alongside their own situated and embodied knowledges. With this grounding they spoke with confidence, taking ownership of the project and responsibility of design decision making. When devising this process, we were determined to place research in the hands of students, to offer them our expertise in exchange for their knowledge which redressed archival gaps. Following Donna Haraway, we sought out these student perspectives “for the sake of the connections and unexpected openings situated knowledges make possible.”[10] This recombining of knowledges and perspectives mutually enriched our understandings of open-air schools.

Construction in Progress, Orchard Primary, Lambeth. Photo: David Roberts

The live-build construction was undertaken entirely by the students, in a balance between autonomy and practicality. Students stepped up to this responsibility, and the unfamiliarity of these skills created an unanticipated moment of parity where those who struggled in a traditional academic context discovered new aptitudes. In our handover of design responsibility and the students’ own discovery of new skills, we began to displace hierarchies of expertise and foster joyful processes of collective learning. Such joy, as bell hooks puts it, “is an act of resistance countering the overwhelming boredom, uninterest, and apathy that so often characterize the way professors and students feel about teaching and learning, about the classroom experience.”[11]

On the final day of school, staff, family and friends gathered to watch a promenade performance in which students performed the use of each pavilion across the school grounds. As they had been speaking about the nature of each pavilion from the start of our engagement, the students had already developed a language to discuss the work, ownership of the narrative of its structure, and in conversations with us, reflected on the process of its creation. Collaborative performance, as Jen Harvie has written, can not only awaken critical awareness and provoke emotion, but offer participants “expanded degrees of agency in making art and its meanings” by enabling participants “to recognize that they actually have sufficient expertise.”[12]

Design Discussions, Orchard Primary, Lambeth. Photo: David Roberts

The final act of the performance involved bringing the co-built pavilions together. While each one was designed for a specific site, they, like the models which had preceded them, could also be combined into a single structure, a gathering of design thinking, situated knowledge, the labour of construction, and our collective learning.

As we reflect on this first iteration of Schools Without Walls and seek to develop it with other school communities, we raise a set of critical questions: What other profound gaps are present in architectural education archives? How can we develop this methodology with schools that do not share such radical architectural and pedagogical histories? What modes of engagement can further shift hierarchies of expertise and empower young people to engage in architectural history and design? How can we articulate these alternative pasts and possible futures anew through student voices?

Arrival Pavilion In-Situ, Orchard Primary, Lambeth. Photo: David Roberts

[1] Historic England. 1999. “Classroom D at former Aspen House Open Air School.” Accessed November 28, 2024. https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1387317?section=official-list-entry

[2] I.G. Jones quoted in London County Council. 1927. Medical Officer of Health Report 1927, Made available on-line by the Wellcome Library in London’s Pulse: Medical Officer of Health Reports, 1848-1972. Accessed November 28, 2024. https://wellcomelibrary.org/moh/report/b18252746/108#?m=0&cv=108&z=-0.1459%2C0.34%2C1.2171%2C0.4761&c=0&s=0.

[3] Boughton, John. 2014. “Aspen House Open Air School, Lambeth: doing ‘the world of good’,” Municipal Dreams. Accessed November 28, 2024. https://municipaldreams.wordpress.com/2014/01/21/aspen-house-open-air-school-lambeth-doing-the-world-of-good/.

[4] Rendell, Jane. 2022. “Situatedness.” Practising Ethics. Accessed November 28, 2024. https://www.practisingethics.org/principles. For a more detailed discussion, see Rendell, Jane. 2020. “Sites, Situations, and other kinds of Situatedness.” Expanded Modes of Practice. Bryony Roberts, ed. special issue of Log 48.

[5] Madison, D. Soyini. 2005. Critical Ethnography: Method, Ethics, and Performance. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 14.

[6] Ansari, Ahmed. 2018. “What a Decolonisation of Design Involves: Two Programmes for Emancipation.” Published in the Beyond Change: Questioning the role of design in times of global transformations conference programme, Basel.

[7] These four themes were introduced and explicated by Rosie Cooper, then Head of Exhibitions at the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill-on-Sea, with whom we discussed the project as part of a knowledge exchange programme with UCL.

[7] Forest School for Sickly Children, Germany, Walter Spickendorff, 1904; Open-Air School, France, Eugène Beaudouin and Marcel Lods, 1936; Impington Village College, England, Walter Gropius and Maxwell Fry, 1939; Tokyo Montessori Kindergarten, Japan, Takaharu and Yui Tezuka, 2007; and Makoko Floating School, Nigeria, Kunlé Adeyemi, 2013.

[9] Ward, Colin. 1990. The Child in the City. Bedford Square Press, ix.

[10] Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 590. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

[11] hooks, bell. 1994. Teaching to Transgress. New York and London: Routledge, 10.

[12] Harvie, Jen. 2013. Fair Play: Art, Performance and Neoliberalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 36, 148.

Traces of Play: Artistic Reflections from the Parklek of Fagerlid, 1957–2020, Hökarängen, Stockholm

Camilla Carlsson

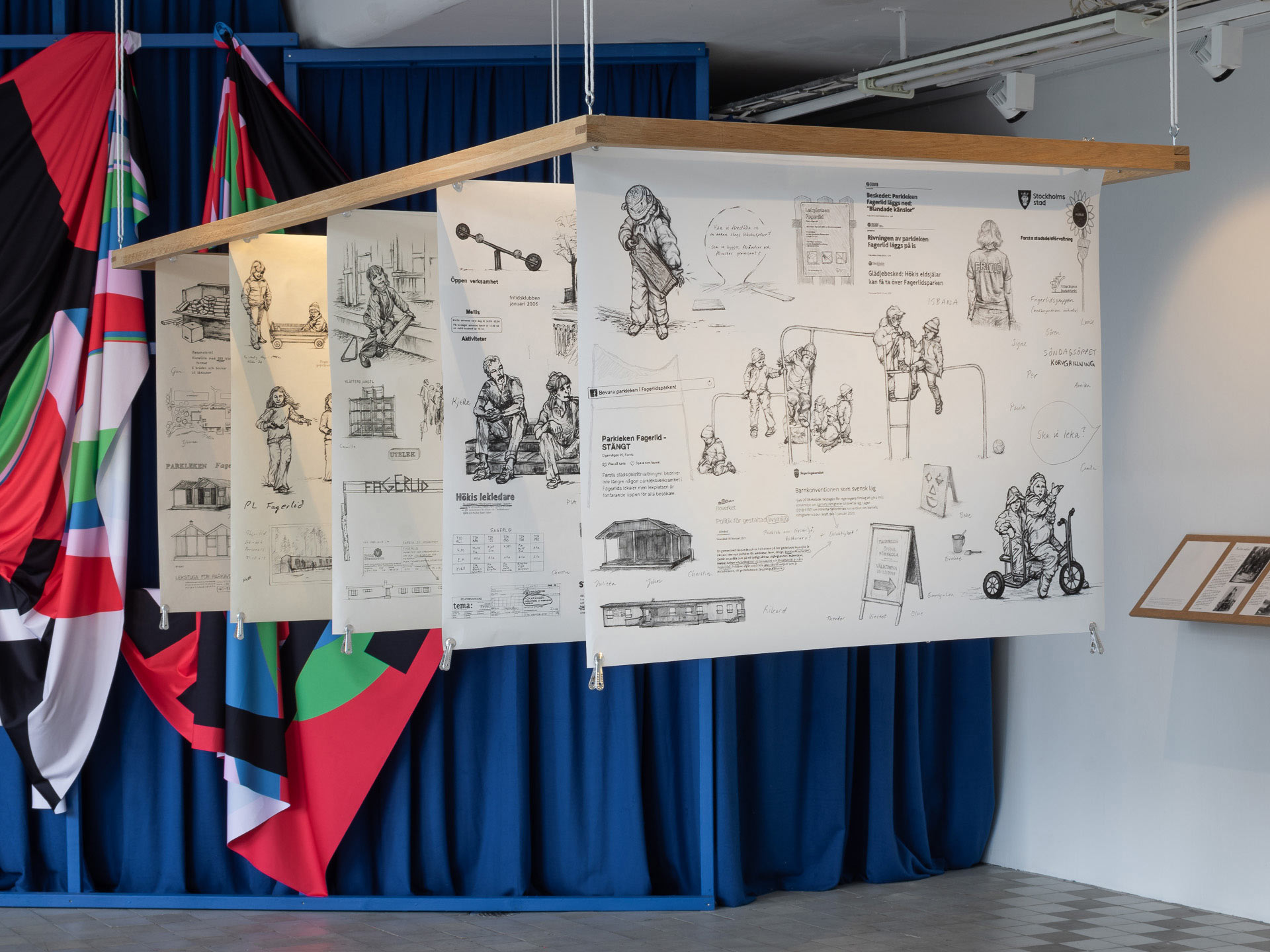

Layers of Play, by Camilla Carlsson, as part of the exhibition, All makt åt fantasin – staden som lekplats (All Power to Fantasy – The City as Playground), May 8 – August 15, 2021, at Konsthall C, Hökarängen, Stockholm. Photo: John Håkansson.

Where did you play as a child? I grew up in a small community with playgrounds around, but my early memories of play are mostly from the nearby forest. As an adult I inadvertently lost interest in play, until I became a parent, and was soon reintroduced to the concept through my young daughter. We lived in a suburb of Stockholm, and I quickly became bored visiting the local playgrounds, with their standardized fixed play equipment. Searching for alternatives, I soon discovered adventure playgrounds—a type of play environment which I find inspiring. I’ve been interested in play ever since, and together with artist John Håkansson have been studying adventure playgrounds from an artistic point of view.

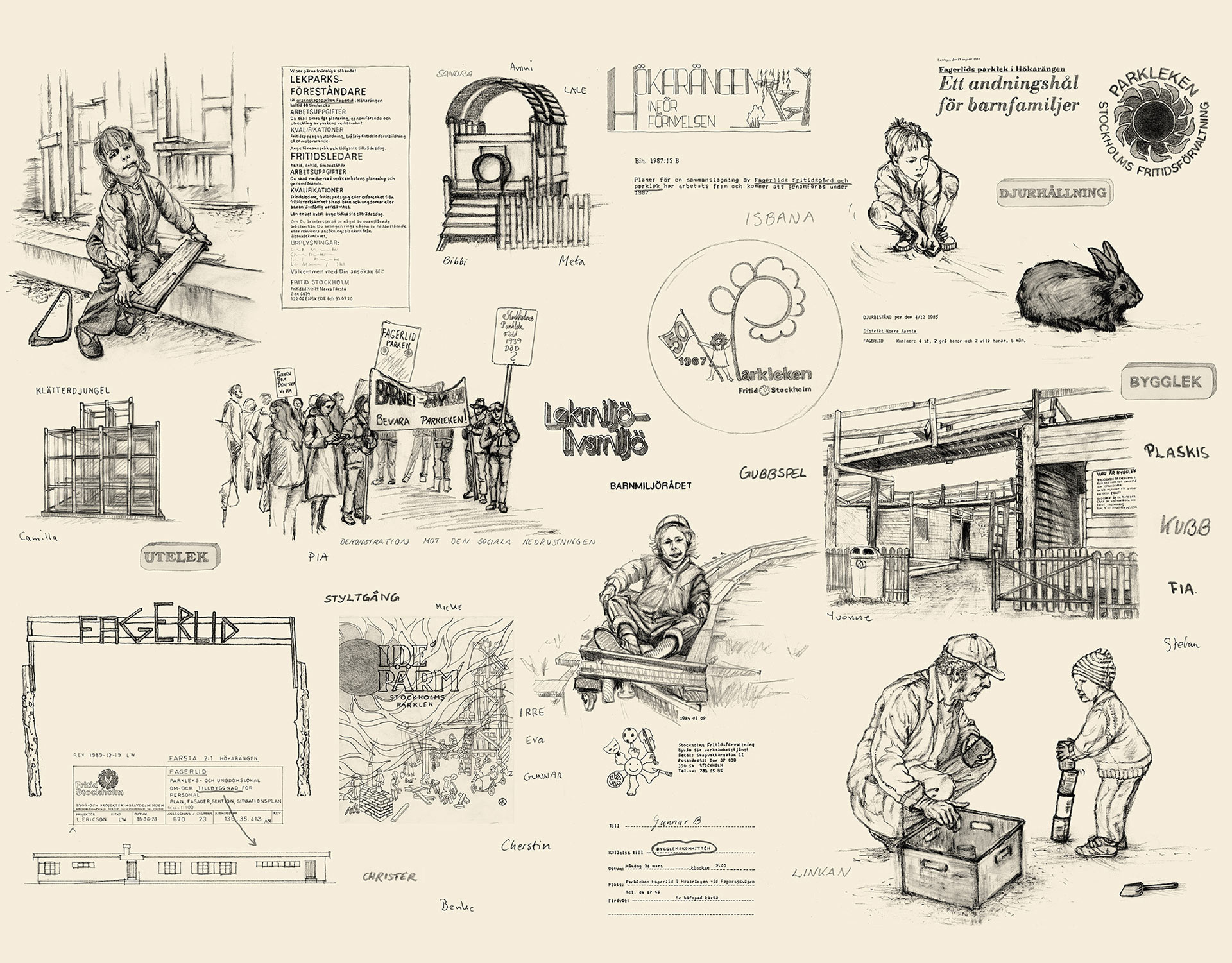

Work on Layers of Play began in February 2020, in response to a local call to action to save Parklek Fagerlid by citizens of Hökarängen, trying to persuade politicians not to close down the Parklek—the local play environment supported by playleaders—where children have been playing since the 1950s. I became engaged in this initiative and used my knowledge about adventure playgrounds to create an archive of play at Parklek Fagerlid, in the form of drawings. The word Parklek translates literally to “park-play” in English, a form of organized play set up by Stockholm’s municipality in 1937. Adventure playgrounds on the other hand originated in Denmark, starting in 1943 with Skrammel-legepladsen in Emdrup, Copenhagen. Both Parklek and adventure playgrounds are the result of visionary urban planning initiatives, which provided specifically designated playgrounds with playleaders, or playworkers, but in contrast to adventure playgrounds, there is little written on Parklek. Today about forty Parkleks remain in Stockholm, but during the 1980s there were over two hundred throughout the city. Parklek Fagerlid coincides with the urban planning of the modernist suburb of Hökarängen, built in the 1950s. It’s carefully planned, situated within a larger green structure connecting two schools, and placed next to the former central laundry, where mothers of the 1950s could watch their children playing through the windows while doing the washing.

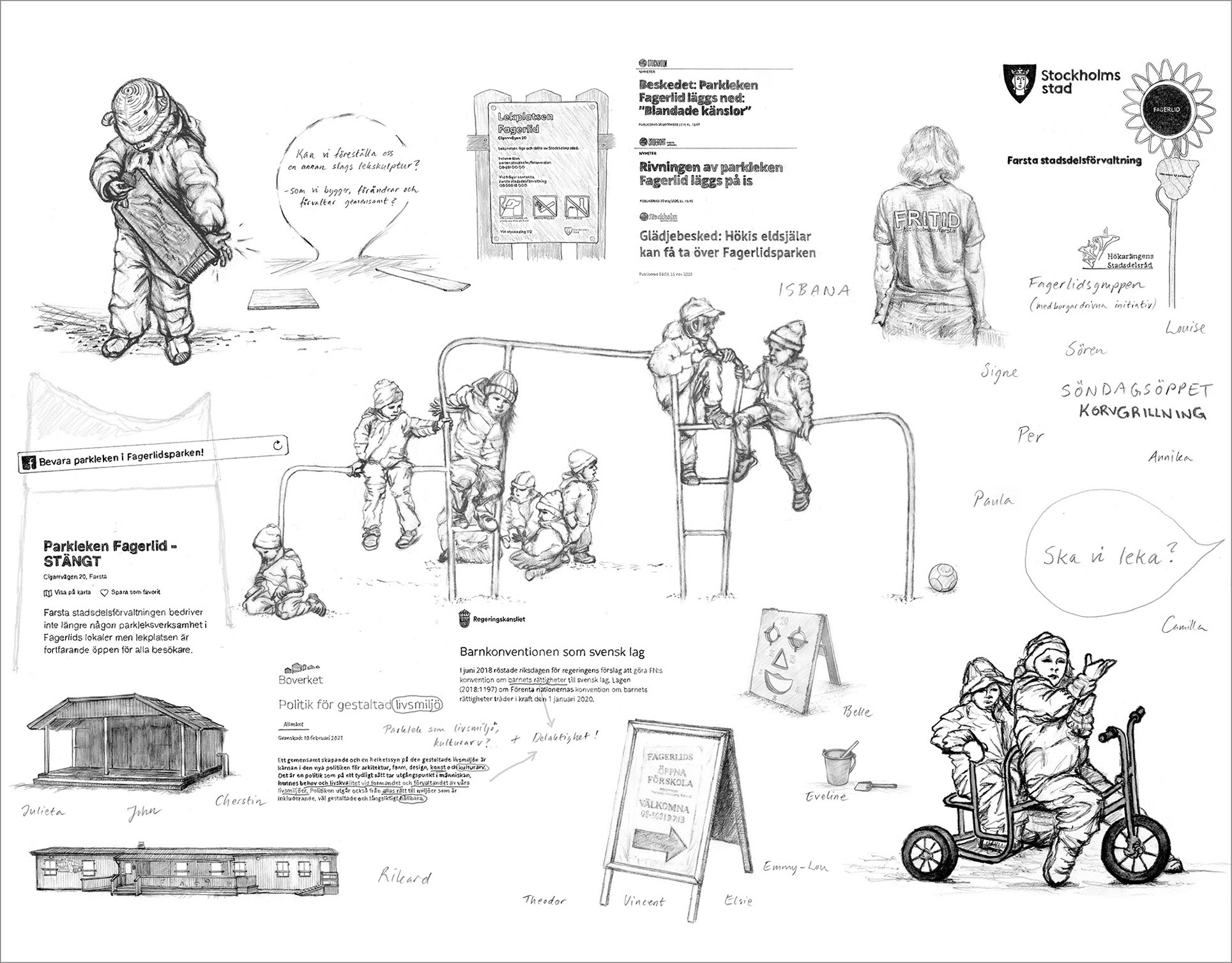

Layers of Play 2020. In June 2020 Parklek Fagerlid was closed due to a political decision. As a result, playleaders’ employments were terminated. Citizens, and the non-profit organization Hökarängens stadsdelsråd (Hökarängen District Council) maintained play activities and continued to hold meetings. In contrast to ordinary playgrounds, Parkleks are marked with a sunflower sign (see the upper right corner). Buildings originate from 1957 and 1971 (lower left corner).

The process of studying the traces of play from Parklek Fagerlid reminded me of putting together pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, without knowing how many pieces there are in total. Fragments of play have been put together into collages, and then transformed into drawings, while many gaps still remain—an acknowledgment to the multiple perspectives that I’m unable to see. In the exhibition I purposely placed the five Layers of Play so that they are partially hiding each other, resisting revealing the whole picture at once. Physical aspects of play take more visible forms than immaterial and mental aspects, yet playfulness can be very elusive to capture, often expressing itself in the interactions between playing persons. These playful acts are difficult to see in photographs, documents, or objects, which is why I prefer using the phrase “traces of play.”

Layers of Play was made specifically for the exhibition All makt åt fantasin – staden som lekplats (All Power to Fantasy – The City as Playground) at Konsthall C—an exhibition that explored play in relation to the city, with a particular focus on the local surroundings of Hökarängen, with Parklek Fagerlid situated just outside the exhibition space. Layers of Play was presented in the main exhibition hall, inspired by the former function of the gallery as a communal laundry building, the five drawings were hung on a wooden frame suspended from the ceiling, reminiscent of drying linen. Each drawing represented a temporal layer of play arranged in a row, one after another chronologically. The oldest layer, representing the 1950s, was drawn on yellow-hued paper, while the papers used for subsequent layers representing the 1970s, 1980s, 2000s, and 2020s gradually becoming brighter, and whiter, as they approached the present day.

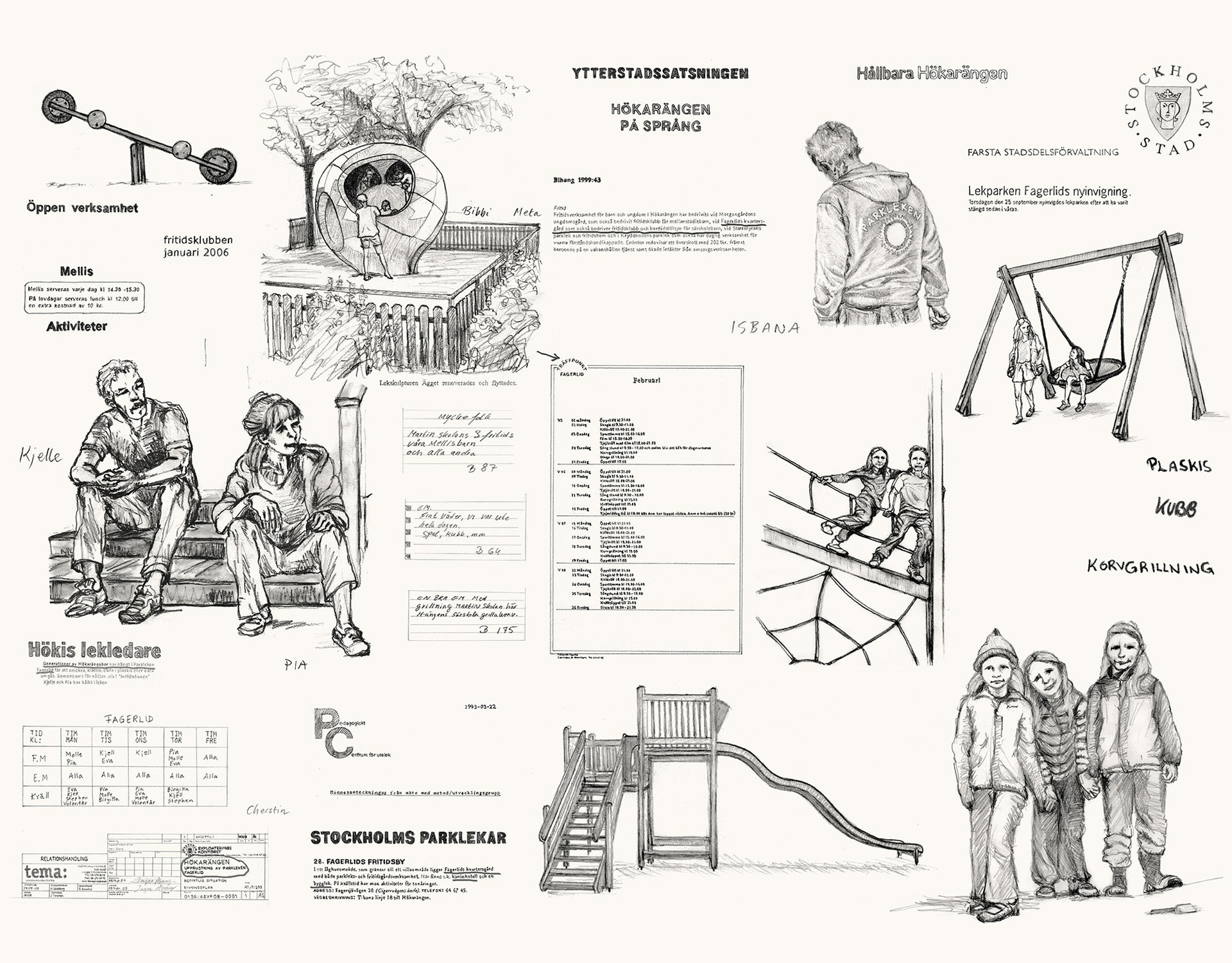

Layers of Play 2000s. Kjell Andersson and Pia Sjökvist (on the left side), worked as playleaders at Parklek Fagerlid for more than 30 years. Their work has been important to the local community. In 2008, the fixed play equipment was replaced.

My research and field studies exploring the play history of the site coincided with the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, however, unlike many other countries, in Sweden outdoor play environments were kept open. The pandemic made Parklek Fagerlid even more important locally as a social outdoor space for children and families. Parklek Fagerlid has been part of the social structure and everyday life of the community of Hökarängen for 70 years. In my research for this artwork, I wanted to capture traces of play through recording shifts in play activities, play materials, play environments, and the playleaders. To get to know more about contemporary play at Parklek Fagerlid I met with two local groups of children, aged between one and five years, and their pedagogues, and we played together every Wednesday on twelve occasions during the spring of 2020. The children’s parents gave me permission to take photographs, which were later translated into drawings (shown in Layers of Play 2020). I also interviewed adults who were, or had been, engaged professionally in Parklek Fagerlid, and others with play memories from the site. Handwritten names in the different Layers of Play, for instance, represent some of those who played at the time.

Before the 1990s both playleaders and the children playing seem to have had more possibilities to engage in the form and materiality of their play environment. I was lucky to find photos of adventure play during the 1980s at Parklek Fagerlid. In adventure playgrounds, the play environment is constantly undergoing changes in participatory processes. This made me wonder, is it possible to unlearn playground design as a product and rather value play as process, participation, and possibilities when designing play environments? I’ve come to realize that the administration and the management of Parklek is important for its continuity. Parklek has been reorganized many times over the years, while the sunflower still symbolizes Parklek, the administration and the management of it has shifted as well as the logotypes representing Stockholm municipality (shown in the upper right corner of the different layers). Politicians have changed too. The playleaders are often the ones who stay longest, connecting to the local community through different play activities. They are more important than the fixed play equipment.

In 2018 the Swedish Parliament decided upon a new architecture policy called Designed Living Environment to guarantee the quality of public spaces, and in 2020, the United Nations Convention on the “Rights of the Child” became a law in Sweden. When the local politicians of Farsta stadsdelsförvaltning (Farsta District Administration)—which includes Hökarängen—took the decision to close Parklek Fagerlid in December 2019, the residents protested. Later, in the spring of 2020, the citizen organization Hökarängens stadsdelsråd (Hökarängen District Council) kept arranging meetings and open hours on Sundays at Parklek Fagerlid, organizing the fireplace and providing play activities, even after the playground was officially closed in June 2020. Local newspapers wrote a series of articles reflecting on the devastating situation. Today however there is hope for a future Layer of Play 2030s at Parklek Fagerlid as the local politicians in Farsta municipality took the residents’ engagement seriously, and on September 26, 2024, decided to build a new Parklek building to restart Parklek Fagerlid in 2027. New playleaders will be employed and promote and participate in children’s play.

Finally, I want to point out that I also value play because of its connection to artistic processes. In both cases you practice your imagination. I do think that play is essential for life, not only for children, but for all ages.

Layers of Play 1980s. Adventure playground at Parklek Fagerlid with playleader Bengt Erik “Linkan” Lindkvist (lower right corner). In 1987, the concept Parklek celebrated 50 years anniversary in Stockholm. 1989 the building at Parklek Fagerlid was enlarged, opening hours were extended (lower left corner).

Layers of Play 1970s. In 1971 a new building was added at Parklek Fagerlid (lower left corner) The original building became a storage building. Parklek is mostly outdoor play activities all year round. The possibility for indoor play activities was appreciated, especially among teenagers.

Layers of Play 1950s. Special play equipment consisted of, for example, the chest with wooden bricks and loose parts (upper left corner). The drawing of the chest is based on a photo by Yngve Hellstöm, whose wife Gun Hellström worked as a playleader at Parklek Fagerlid. The building from 1957 (lower left corner) was demolished in 2023.

Situated Pedagogies: Learning from the Urban Studies Centres Movement 1968–1988

Sol Pérez-Martínez

Notting Dale Urban Studies Centre collage, London. Photos: Notting Dale, The Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea Local Studies & Archives (1980c). Image: Courtesy of Sol Pérez Martínez and The Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea Local Studies & Archives.

Despite the proven significance of the built environment for people’s health and well-being—backed up by medical, public health, psychological, and sociological studies—the creation of the built environment in the UK is still dominated by a limited demographic of professionals who are not representative of the world’s population in terms of gender, race, or ability (Pérez Martínez 2022). These demographics matter because it is unlikely that one homogenous group of people can imagine the spatial needs of a highly diverse population. So, if we want to develop equitable, diverse and inclusive environments, we need a wide range of people involved in creating the physical environment to respond fully to the needs and desires of a varied global population, from users to policy creators. To do so, the first step is to engage different publics in architecture and the built environment so that more groups feel comfortable talking about the environment around them and want to take part in its improvement, from childhood to old age.

In Learn Where You Stand, I propose ‘situated pedagogies’ as an educational approach to promote civic and social engagement in architecture and the built environment, including users, professionals and officials. Situated pedagogies aim to help people learn from the physical world around them, engage with it and participate in changing it. It also encourages people to explore their social, economic and political stance and how this positioning unconsciously affects their way of ‘reading the world’ – to quote educational theorist Paulo Freire (Freire 2021, 20).

The title of this research is a play on words from Dig Where You Stand, a social movement and a manual for bottom-up history started by Swedish author Sven Lindqvist (Lindqvist 1978). Lindqvist challenged the idea that only company owners and directors could write the histories of businesses and provided workers with a manual to write about their jobs from their perspective. According to writer Ken Worpole, who was involved in the new history movement in 1970s Britain, Dig Where You Stand was ‘the motto of the day’ fuelling an ongoing project of history from below (Worpole 1980, 288). Similarly, anarchist writer Colin Ward challenged the idea that architects and planners were the only ones entitled to have a say in the world we all live in. Learn Where You Stand is my interpretation of the campaign by Ward and planning journalist Anthony Fyson at the beginning of the 1970s at the Town and Country Association for an urban and issue-based education that would allow people to become ‘masters of their own environment’, regardless of their age (Ward 1995). This campaign, along with other actors explored in my research, motivated the creation of the Urban Studies Centres (USCs), a new type of organisation scattered across the UK that, for more than twenty years, helped people learn where they stood, physically and politically.

Imagining the Urban Studies Centres. Print: CUSC. ‘Council for Urban Studies Centres First Report 1974’. London: CUSC, 1974. Image courtesy of Sol Pérez-Martínez

Urban Studies Centres (USCs) were a network of British organisations for public education and citizen involvement in architecture and planning during the 1970s and 1980s, initially advocated by Ward and Fyson. In Learn Where You Stand, I argued that USCs offer valuable insights into three contemporary challenges for equitable environments: the social engagement of architects and built environment professionals, the spatial engagement of educators, and the collaboration between educators, architects and citizens for spatial justice. More importantly, the USCs offered a series of historical examples of ‘situated pedagogies’, published regularly in the Bulletin of Environmental Education (BEE), a monthly publication edited by Ward, Fyson and art educator Eileen Adams. I saw in BEE a distinct pedagogical approach combining education, architecture, and citizenship, which has the potential to increase civic engagement in architecture and the built environment.

Ward’s ideas were central to this grounded form of learning from the environment and the organic network of people that put the USCs into action, inspiring practitioners from artists to geographers, educators to architects. Ward is known in architecture and education for his book The Child in the City (Ward 1979), but he also wrote Anarchy in Action (Ward 1973), a central book for everyday social anarchy and Streetwork with Anthony Fyson, where he advocated for the study of urban areas as a path to active citizenship(Ward and Fyson 1973). Through his writings and talks about the relation between people and the environment from a social anarchist perspective, he highlighted the potential of transformative change in everyday, small-scale actions, triggering a grid of almost forty self-organised urban learning centres across the UK to promote the local improvement of the built environment.

Book cover Streetwork. Photo of Ward, Colin, and Anthony Fyson. 1973. Streetwork: The Exploding School. Routledge & K. Paul. Image courtesy of Sol Pérez-Martínez

Urban Studies Centres emerged as grassroots hubs to gain the awareness, skills, and agency needed to influence and change the local built environment. These centres responded to the belief that true civic participation in city-making requires a foundation of environmental literacy. By 1980, 31 of these centres were active across the UK (Council for Urban Studies Centres 1981). Without a unified framework or central institution, the centres developed organically, with each reflecting the unique context of its location—whether in terms of structure, size, programming, or funding. They functioned as adaptable archives, drawing on local resources and the diverse talents of the people involved. But above all, these centres responded directly to the public frustration with the urban issues stemming from years of top-down planning. They served a dual purpose: empowering citizens to shape their surroundings while encouraging professionals to recognise the importance of listening to people’s voices.

The USCs used their local urban environment as a primary resource for their pedagogical activities, which resulted from the collaboration between environmental professionals and educators. Through the urban studies centres, Ward advocated for issue-based learning and place-based methods, which gave the learner an active role and considered learning a situated practice. Ward understood that for environmental education to succeed, he needed to talk to three groups: school communities, politicians and civil servants in charge of social policy and architects and planners, represented in his series of ‘talking’ books. (Ward 1995; 1996; 2000) In my research, I also address these three groups and propose situated pedagogies as a practice that bridges architecture and education, helping architects, educators, and citizens work together towards equitable built environments. Even though the USCs’ main aim was to widen participation in the construction of cities, I argue that they also proposed a way to transform and deschool architecture through situated pedagogies as a side effect by making architectural and urban education publicly available (Pérez-Martínez 2020).

Children at work at the Notting Dale Urban Studies Centre. Print: CUSC. 1983. ‘Council for Urban Studies Centres Third Report 1983’. 3. London: CUSC. Image courtesy of Sol Pérez-Martínez

Arriving at situated pedagogies was not straightforward. During this research, I moved back and forth between multiple types of pedagogies, trying to find the educational approach that could operate as a common ground for the collaboration between architects, educators and citizens. In that process, I was particularly interested (and publicly lectured about) different terms, starting from ‘place-based pedagogies’, which looked closely at the material world but did not commit to social change or justice and concentrated on natural environments. Then I moved on to ‘urban pedagogies’, which was very close to my interests but missed a transformative edge that made me transition to ‘critical urban pedagogies’. This last term derived from the critical pedagogies of Freire, but later, I rejected a modern approach to education based on theological emancipatory thinking, moving to ‘radical urban pedagogies’. However, this term ignores that not all place-based learning happens in urban areas. I started using ‘civic pedagogies’ to highlight the connection of this education approach with the interests of citizens – regardless of whether or not they are based in urban areas. Nonetheless, for some people, civic meant governmental, missing the point of an approach different from other institutional forms of schooling. Finally, I found a home in ‘situated pedagogies’, a term first developed by educators and feminists Patti Lather and Elizabeth Ellsworth, which was feminist, sociomaterial and radical. For Lather and Ellsworth, ‘all classroom practices are situated – that is, they take place in institutions, historical moments, cultural and social fields, and in response to individual and social constraints’ and therefore are ‘sites of political and cultural struggle’ (Lather and Ellsworth 1996, 70–71). Their concept of situated pedagogies challenged critical pedagogies, which assumed that critical or radical educators could teach liberation or that teachers must empower students to become fully conscious agents because they already are. They defined situated pedagogies as those educational practices that respond to ‘the materials present in the particulars of the moment’ (Lather and Ellsworth 1996, 70). They take into account the situation’s historical, geographical and institutional characteristics as well as the cultural background of teachers and students.

Educator John Kitchens also argues for a situated pedagogy that connects critical geography and pedagogy, especially through the work of the Situationist International and their notions of situations, the derive, and psychogeography (Kitchens 2009, 241). Kitchens traces back the idea of a situated pedagogy to John Dewey’s Experience and Education, where he argues for an education based on the philosophy of experience. In critical pedagogy, Kitchens finds clear calls for situatedness in education as a path to social justice in Brazilian educator Paulo Freire’s theory of conscientisation, where students ‘reflect on their “situationality” to the extent that they are challenged by it to act upon it’ (Freire 1996, 90).

Implementing a situated pedagogies approach with the project ‘Aula Abierta: Taller Patrimonio de Rengo’. 2017. Photograph by Fernanda Claro. Image courtesy of Sol Pérez-Martínez

For Kitchens, a situated pedagogy ‘requires students pay attention to their environment, to practice awareness and listening to what places have to tell us, and furthermore, to decode places politically, socially, and historically’ (Kitchens 2009, 244). Close to the concept of situated pedagogies is Vivienne Bozalek’s ‘socially just pedagogies’, which ‘incorporates Haraway’s notions of situated knowledges … transdisciplinarity … the natural sciences and the humanities, as well as more than human others in education projects’ (Bozalek 2018). Bozalek’s proposal advocates for joy and desire in education as a force for learning, transforming criticality into a pleasant activity.

Drawing on the experience of the USC Network, I argue that a positive collaboration between architects, educators and citizens is crucial to widening participation in architecture since it will allow each group to learn from each other. A network of actors or spaces, like the Urban Studies Centres or the USC Network, can facilitate this collaboration and host a shared pedagogical approach which is situated, people-centred, place-based, active and critical, here called situated pedagogies. Following the USCs legacies, I advocate for situated pedagogies today as a first step towards creating inclusive environments for all.

Implementing a situated pedagogies approach with the project ‘Co-creating an urban archive’ exhibited at the Bartlett School of Architecture. 2018. Photograph by Stephanie Fell. Image courtesy of Sol Pérez Martínez

References

Bozalek, Vivienne. 2018. ‘Socially Just Pedagogies’. In Posthuman Glossary, by Rosi Braidotti and Maria Hlavajova. Theory in the New Humanities. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, Bloomsbury Academic.

Council for Urban Studies Centres. 1981. ‘Urban Studies in the 80’s : The Council for Urban Studies Centres’ 3rd Report’. 3. London: Council for Urban Studies Centres. Courtesy of Lynne Dixon.

Freire, Paulo. 1996. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos. 2Rev Ed edition. Penguin.

———. 2021. ‘Reading the World and Reading the Word: An Interview with Paulo Freire’, 8.

Kitchens, John. 2009. ‘Situated Pedagogy and the Situationist International: Countering a Pedagogy of Placelessness’. Educational Studies 45 (3): 240–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131940902910958.

Lather, Patti, and Elizabeth Ellsworth. 1996. ‘This Issue: Situated Pedagogies—Classroom Practices in Postmodern Times’. Theory Into Practice 35 (2): 70–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849609543704.

Lindqvist, Sven. 1978. Dig Where You Stand: How to Research a Job.

Pérez Martínez, Soledad. 2022. ‘Learn Where You Stand: Lessons for Civic Engagement in Architecture and the Built Environment from the Urban Studies Centres Network and Their Situated Pedagogies in Britain 1968–1988’. Doctoral Thesis, UCL (University College London). Doctoral, UCL (University College London). https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10142987/.

Pérez-Martínez, Sol. 2020. ‘Deschooling Architecture’. E-Flux. E-Flux Architecture. 12 March 2020. https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/education/322673/deschooling-architecture/.

Ward, Colin. 1973. Anarchy in Action. 1st ed. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

———. 1979. The Child in the City. New York: Penguin Harmondsworth.

———. 1995. Talking Schools: Ten Lectures. Freedom Press.

———. 1996. Talking to Architects: Ten Lectures. Freedom Press.

———. 2000. Social Policy: An Anarchist Response. Freedom Press.

Ward, Colin, and Anthony Fyson. 1973. Streetwork: The Exploding School. Routledge & K. Paul.

Worpole, Ken. 1980. ‘History Workshop 2’. New Statesman, 22 February 1980.

Mapping the Tradition of Environmental Art Education in Finland

Henrika Ylirisku

In Finnish visual art education, an emphasis on environmental themes has been a recognisable thread for decades, and internationally, Finland has become known for its unique pioneer work in merging environmental topics and environmental education with art education.

I begin this visual essay by presenting the main characteristics and approaches related to environmental themes that emerged in Finnish art education training over the past decades, with a specific focus on the training of art teachers. Until 1990, art teachers in Finland were only trained at one university, Aalto University (earlier University of Arts and Design), and since then also at the University of Lapland. Teaching at these two universities has had (and still has) a significant impact on the types of art education perspectives and practices that Finnish art educators adopted and developed within their own professional environments—be it in in primary and early secondary school education, museums, and liberal adult education in the arts or elsewhere.

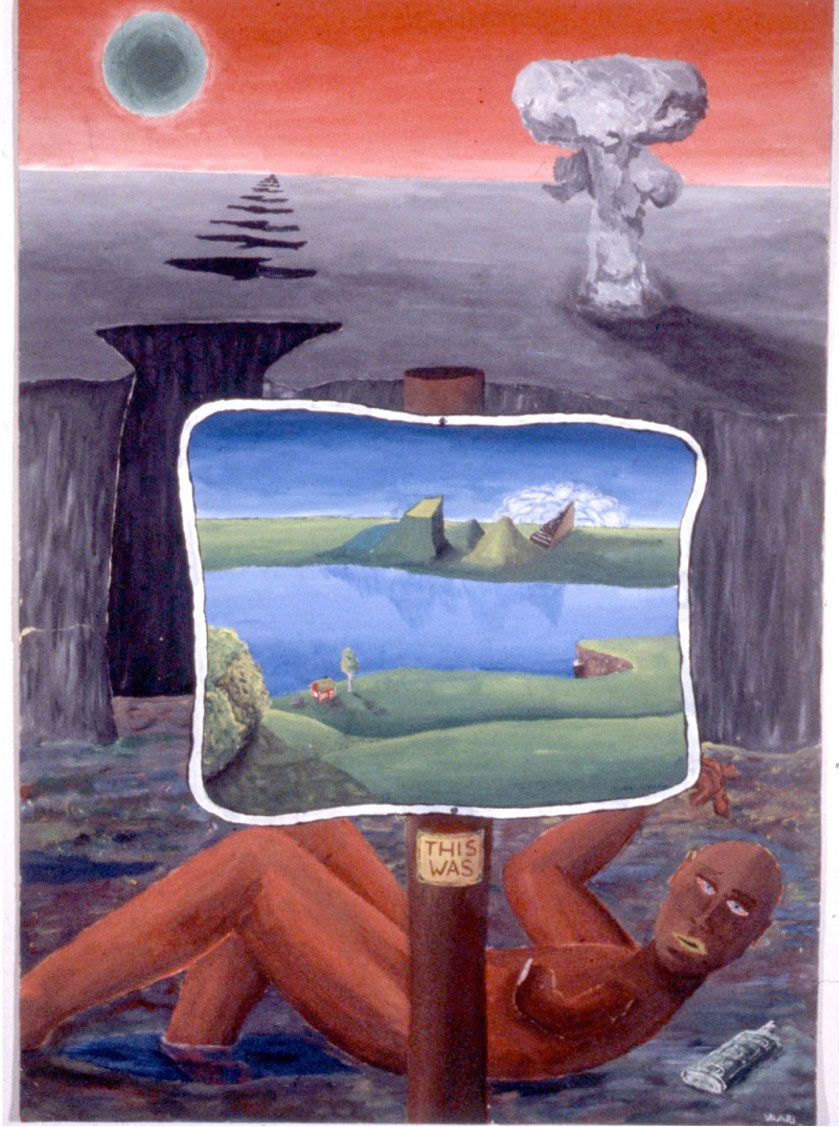

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Finnish art education was characterised by a socially conscious and culturally critical approach.[2] Student artworks addressing social and environmental issues were a prominent feature in art exhibitions, both within as well as outside the schools.[2] A critical image analysis method, known as the polarising method, adopted from Swedish art educators, promoted the creation of poster-like collages and comparisons when studying worldwide eco-social challenges, such as pollution, war, and hunger. Over time, this culturally critical approach became known as the ‘pedagogy of the screaming images’ due to its emphasis on threats, problems, and confrontation.[3]

I begin this visual essay by presenting the main characteristics and approaches related to environmental themes that emerged in Finnish art education training over the past decades, with a specific focus on the training of art teachers. Until 1990, art teachers in Finland were only trained at one university, Aalto University (earlier University of Arts and Design), and since then also at the University of Lapland. Teaching at these two universities has had (and still has) a significant impact on the types of art education perspectives and practices that Finnish art educators adopted and developed within their own professional environments—be it in in primary and early secondary school education, museums, and liberal adult education in the arts or elsewhere.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Finnish art education was characterized by a socially conscious and culturally critical approach1. Student artworks addressing social and environmental issues were a prominent feature in art exhibitions, both within as well as outside the schools2. A critical image analysis method, known as the polarizing method, adopted from Swedish art educators, promoted the creation of poster-like collages and comparisons when studying worldwide eco-social challenges, such as pollution, war, and hunger. Over time, this culturally critical approach became known as the ‘pedagogy of the screaming images’ due to its emphasis on threats, problems, and confrontation.3

Student artwork by Timo Vaari (15 years) from Kannaksen yhteislyseo (upper secondary school), Lahti, Finland. Image: Archive of Art Education, Aalto University Archives

Despite good intentions, the politically charged images of the 1970s “failed to empower those who had created them,”[4] leading this pedagogical approach to an impasse. Despite these pedagogical challenges, the strong environmental awareness that influenced the studies of art teachers at the time had far-reaching impacts on the development of Finnish school curriculum. In the 1970s, during the school reform that established a new comprehensive school system for all children, art became the first subject to integrate environmental education as one of the core content areas.

In the early 1980s, the critical cultural approach began to shift toward art pedagogies emphasising personal aesthetic experience and environmental sensitivity.[5] New forms of contemporary art—such as place-based environmental and land art, performance art, and community art—inspired faculty and students in the art teacher education to develop innovative methods for integrating artistic practice, pedagogy, and engagement with places and environments. The development of new environmental pedagogies theoretically drew from environmental aesthetics and psychology, eco-philosophy, and gestalt therapy. It also emerged as a continuation of educational philosophy that regards teaching as a holistic activity akin to art (following Elliot Eisner and J. A. Hollo) and emphasised experience as a foundation for learning (following Marjo Räsänen).[6] By the mid-1990s, this approach became known as arts-based environmental education.

Children observing an installation called The Past. Art education students from University of Arts and Design organized a junk art workshop at the school yard of Tehtaankatu school in 1990. Photo: Pirkko Pohjakallio

Arts-based environmental education aimed to promote students’ environmental understanding by cultivating skills of environmental perception and encouraging the expression of environmental experiences through art. Additionally, the approach emphasised taking concrete actions for the environment, such as community art events, envisioning of more sustainable futures, design education, and learning to repurpose abandoned objects and waste as materials for art (see image 2). While art-based environmental education provided an open framework for exploring the human-nature relations, many of the diverse practices within this approach leaned on interdisciplinary collaboration. Working with experts from various fields facilitated a multidimensional understanding of the phenomena under examination, encompassing both cultural-historical and scientific perspectives.

A mandala created from natural materials. Such environmental art activities have been popular in arts-based environmental education with children. Photo: Henrika Ylirisku

Over the past two decades in Finland, there has not been a single, identifiable approach to environmental art education, but instead multiple parallel approaches have emerged, some of which overlap and emphasise different aspects.

In art teacher education in Helsinki, critical visual culture pedagogy, adopted from the United States, gained prominence in the early 2000s, and more broadly, an emphasis on promoting social justice and societal activism have become integral parts of art education.[7] In school contexts, ecological values and sustainability issues related to the environment are often approached through design and architecture, and arts-based environmental education practices continue to be used.[8]

At the University of Lapland, where the art teacher education was established in 1990, community-based environmental art education practices have been developed over the past few decades, specifically designed to address the needs of local Arctic communities and environments. Art education teachers and students have collaboratively developed place-based pedagogical activities that typically involve interdisciplinary collaboration with experts from various fields and local communities. These working methods often incorporate dialogical, performative, and community-based contemporary art practices, with materials commonly including snow, ice, fire and wood (see image 4).[9] In the North, particular emphasis has been placed on themes such as decolonisation and cultural sustainability (Jokela 2016).

Collaborative sculpting during an artistic community and environmental art project in the village of Neiden, North Norway, as part of the international Border Dialogues art event in 2006. Photo: Maria Huhmarniemi

Although the diverse forms of environmental art education in Finland have evolved in response to local interests and needs, societal and educational policy trends, and shifts within the art world, certain common elements characterize the approaches currently in use. A defining characteristic of Finnish environmental art education is its place-based, critical, and experiential pedagogical orientation, complemented by the versatile application of contemporary art practices.

The approaches of earlier decades can be regarded as pioneering efforts to foster societally active and responsible roles for art and art education. Building on this foundation, environmental art education today increasingly appears to shape the entire field of arts education, guiding it toward the promotion of eco-social sustainability. This shift is evident, for example, in the community-oriented environmental art education activities developed at the University of Lapland.

My review of international literature on environmental art education indicates that recent Finnish approaches are largely aligned with international perspectives. Although approaches to environmental art education may vary significantly and are not always compatible, five distinct emphasis areas can be identified across both Finnish and international approaches.

1) For certain approaches, ecological concern related to the material dimensions of artistic practice are central. For example, the use of recycled materials in artmaking or transitioning to eco-friendly art supplies can serve as initial steps toward more sustainable practices. 2) Other approaches emphasize cultivating environmental sensitivity, often through exercises that engage multisensory perceptions and personal, place-based experiences. 3) This emphasis aligns with the creation and strengthening of meanings and community building. Practices of socially engaged art, for example, create spaces for collective gathering, dialogue, negotiation, and the sharing of diverse experiences, emotions, and beliefs. 4) Additionally, some environmental art education approaches concentrate on critical cultural analysis, enabling the examination of normative values, power structures, stereotypes, and beliefs. Media imagery and other forms of visual culture often provide the material for such analysis. 5) Critical thinking in these approaches is frequently intertwined with action, aiming to facilitate concrete social and environmental change. This can manifest in various forms, such as societal activism, artistic interventions, or the improvement of local living environments through artistic means.

Environmental art education holds diverse potentials for environmental learning. When the artistic approach is integrated holistically into pedagogical processes, it offers a unique perspective on examining the relationships between humans and the world. Working methods inspired by contemporary art encourage engagement with open-ended, complex, experimental processes. Moreover, they foster curiosity and integrate multiple forms of knowledge, including embodied and sensory knowledge, emotions and affects, imagination, and scientific understanding. Environmental art education projects also serve as excellent platforms for collaboration and interaction among experts from diverse fields and communities. At their best, such projects can generate processes that revitalize and empower both environments and communities, while promoting informed, caring, and responsible environmental attitudes.

Despite its strengths, the tradition and practices of environmental art education have their limitations and shortcomings. A significant challenge arises from the theoretical and philosophical groundings of the field. While environmental art education has sought to challenge cultural assumptions about the separation between humans and nature and has critiqued anthropocentric human-nature relations that instrumentalize and dominate the natural world, the humanist frameworks it relies upon remains problematically entrenched in the same anthropocentric and dualistic logics.

The contradictions within the theoretical frames applied in environmental art education can lead to challenges such as biased and narrow views of nature. This may result in an emphasis on aspects of human-nature relationships that are pleasing and positive from a human perspective—harmonious and healing—while neglecting more complex, troubling dimensions. Such an approach risks fostering an apolitical innocence, ignoring the power dynamics and injustices inherent in human-nature relationships, as well as the disparities in people’s access to natural environments. This romanticized orientation toward nature makes it difficult to address for example destructive, frightening, strange, and uncanny aspects of human-nature relations.

Another example of the incoherence arising from the contradiction between the underlying assumptions of theoretical frameworks and the objectives of teaching can be found in the conflicting ideals related to human agency. Many environmental protection discourses position humans as stewards of the environment. While this perspective can foster an understanding of the importance of nature conservation and encourage the development of responsible attitudes, it does not facilitate a ”radical rethinking of human subjectivity and relations in ways that question human exceptionalism”10]. In the environmental ethical stewardship model, humans are attributed with exceptional agency: they are seen as holding the power not only to destroy but also to repair and solve. Consequently, when environmental art education draws on stewardship discourses, it risks perpetuating the division between nature and culture.

Recent initiatives have sought to reorient the theoretical and philosophical groundings of environmental art education by using, for example, environmental, critical, feminist, posthumanist and new materialist theories. Employing these theories allows for decentering the human exceptionalism and questioning of divisive categories between human and nonhuman, and nature and culture[11]. Such approaches contribute to the development of future conceptualizations of environmental art education that attend to complex material and multispecies entanglements, while also addressing the ethical and political dimensions of these entanglements.

[1] This text draws extensively on my dissertation, Ylirisku, Henrika. 2021. “Reorienting environmental art education.” PhD diss., Aalto ARTS Books, Aalto University publication series Doctoral Dissertations 9/2021 and Ylirisku, Henrika. 2016. ”Ympäristöopetus kuvataidekasvattajien koulutuksessa.” In Taidekasvatus ympäristöhuolen aikakaudella, edited by A. Suominen. Aalto ARTS Books, as well as on Pohjakallio, Pirkko. 2005. ”Miksi kuvista? Koulun kuvataideopetuksen muuttuvat perustelut.” PhD diss. University of Arts and Design Helsinki, Taideteollisen korkeakoulun julkaisusarja A 60; Pohjakallio, Pirkko. 2010. “Mapping Environmental Education Approaches in Finnish Art Education.” In Research in Arts and Education 2010 (2): 67–76; and Mantere, Meri-Helga. 1995. ”Suunnan valintaa ympäristökasvatuksen maisemissa.” In Maan kuva: Kirjoituksia taiteeseen perustuvasta ympäristökasvatuksesta, edited by M.-H. Mantere. Taideteollinen korkeakoulu.

[2] Pohjakallio 2005, 223.

[3] Pohjakallio, Pirkko. 2016. “Ympäristö, kasvatus ja taide – avoimia ja muuttuvia käsitteitä kuvataideopettajakoulutuksessa.” In Taidekasvatus ympäristöhuolen aikakaudella, edited by A. Suominen. Aalto ARTS Books, 120.

[4] Pohjakallio 2010, 72.

[5] Pohjakallio 2010, 73; Ylirisku 2021.

[6] Pohjakallio 2016, 59.

[7] Kallio-Tavin, Mira. 2015. “Becoming culturally diversified.” In Conversations on Finnish Art Education, edited by M. Kallio-Tavin and J. Pullinen. Aalto ARTS Books.

[8] van Boeckel, Jan. 2013. “At the heart of art and earth: An exploration of practices in arts-based environmental education.” PhD diss., Aalto University, Aalto ARTS Books; Humaloja, Tiina. 2016. Merkityksellinen maisema: Näkökulmia taideperustaiseen ympäristökasvatukseen puutarhassa ja metsässä. Lasten ja nuorten puutarhayhdistys ry and Nuorisoasiainkeskus.

[9] Hiltunen, Mirja. 2009. “Yhteisöllinen taidekasvatus: Performatiivisesti pohjoisen sosiokulttuurisissa ympäristöissä.” PhD diss., University of Lapland; Jokela, Timo, Hiltunen, Mirja and Härkönen, Elina. 2015. ”Contemporary art education meets the international, multicultural north.” In Conversations on Finnish Art Education, edited by M. Kallio-Tavin and J. Pullinen. Aalto ARTS Books.

[10] Ylirisku 2021, 83.

[11] Rousell, David, Lasczik Cutcher, Alexandra, Cook, Peter, J. and Irwin, Rita, L. 2020. “Propositions for an environmental arts pedagogy: A/r/tographic experimentations with movement and materiality.” In Research handbook on childhoodnature: Assemblages of childhood and nature research, edited by A., Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, K., Malone, and H. E. Barratt. Springer; Rousell, David, Hickey-Moody, Anna and Aleksic, Jelena. 2024. “Intersectional and decolonial perspectives on an incorporeal materialism: Towards an elemental philosophy of art education.” International Journal of Art & Design Education 43, no. 3: 343–62; Ylirisku 2021.

Learnings /Unlearnings: Environmental Pedagogies, Play, Policies, and Spatial Design responds to the call Designed Living Environment—Architecture, Form, Design, Art and Cultural Heritage in Public Spaces, and is funded by Formas—a Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development with the Swedish National Board of Housing, Building and Planning; ArkDes; the Swedish National Heritage Board; and the Public Arts Agency Sweden, under the grant agreement number 2020-02402.

Thank you to Färgfabriken in Stockholm, especially to Karin Englund and Anna-Karin Wulgué for hosting Learnings/Unlearnings.

is an architect and a PhD student at the Royal Danish Academy in Copenhagen, where she lives. Her research explores ecofeminist environments in Sweden and Denmark (1900–1980), focusing on the intersections between critical farming practices, feminist learning spaces, and collective maintenance processes. Previously, Anne Pind worked as an architect in the field of conservation and maintenance. She is an experienced educator and a member of the research collective Metaphorical Houses at the Royal Danish Academy. Additionally, she has served as an editor for the Danish architecture magazine Arkitekten and contributed architectural criticism to the daily newspaper Politiken.

is an architect and lecturer in architecture at the University of Reading with a specialization in representation and communication. Her research explores the ways we tell stories about place, using collaborative acts of making and writing to question how fictional worlds influence and reflect the worlds we inhabit.

is the co-founder of MATT+FIONA, an award-winning architecture education organisation, building on her long-term career in cultural learning and outreach at Open City, the RIBA and the Design Museum. She endeavours to bridge design and participation in her practice, leading on tailored engagement with children and young people.

is Senior Lecturer at University of the Arts London and teaches at Camberwell College of Arts and Central Saint Martins. His research interests lie in interdisciplinary collaborative pedagogy, creative research methods and the architecture of progressive education.

is Associate Professor at the Bartlett School of Architecture and part of art and architecture collectives Fugitive Images and BREAK//LINE. David’s research, art and cultural activist practice engages community groups threatened by urban policy, empowers ethical reasoning in built environment practice, and extends architectural education to school children.

is an artist based in Stockholm. Her practice includes exhibitions, public art commissions, art educational assignments and participatory, creative processes with children. She holds a Master of Fine Arts from Malmö Art Academy, Lund University, and educations in Public Art, Architecture, and Art Education from Konstfack, Royal Institute of Art and Reggio Emilia Institute in Stockholm. www.camillacarlsson.se

is an architect, educator and postdoctoral researcher in the ERC project Women Writing Architecture 1700-1900 at ETH Zürich. Her last public building in Chile motivated her research about equality and education in architecture, with particular attention to the experiences of women, children and marginalized groups. She holds master’s degrees in architecture and architectural history and a PhD in Architecture & Education from the Bartlett School of Architecture and the Institute of Education, UCL. Sol has taught at The Bartlett and Universidad Católica de Chile and lectured internationally, including at the Whitechapel Gallery, Tate Exchange and Nottingham Contemporary. www.solperezmartinez.com

DA, Doctor of Arts, is an art pedagogue and an artist-researcher, working as a university lecturer of art education at Aalto University, in Finland. Henrika’s practice intersects arts and art education, environmental education and multispecies research. Recently, she has published on the theoretical groundings of environmental art education, and multispecies forest relations. In her current research, Henrika explores shifting nature-culture relations and the atmospheres of young people growing up amidst the environmental crisis. She enjoys movement-based practices and has developed artistic walking methodologies, inspired by the working methods of environmental and performance arts.