Epistemic Invalidation in Hong Kong’s Anti-Guide Dog System Campaign

Lo Keng Chi

CATEGORY

Lo Keng Chi’s research contributes to the broader discourse on ableism and animal rights, aiming to foster a deeper understanding of the intersectionality within and between these two movements in the context of Hong Kong’s rehabilitation culture.

Recent negative news stories surrounding guide dog service organisations in Hong Kong have attracted significant attention in the media. This increased scrutiny has prompted animal conservation advocates in Hong Kong to question the efficacy of the guide dog system. Unusual in Asian contexts, these critiques seem to have originated from the United Kingdom, where media personality Wendy Turner Webster, a staunch animal rights advocate, argued against the recruitment of working dogs, claiming there should be no contractual agreement with them. Shockingly, there were reports of animal rights activists confronting visually impaired individuals in public spaces. This rhetoric has gradually spread on social media platforms in Hong Kong and Taiwan over the past couple of years, gaining traction amongst animal rights supporters, despite facing scepticism from many.

As a researcher in Disability studies and a visually impaired person who does not use a guide dog, I aim to provide an academic review on the viewpoints of animal rights advocates in Hong Kong regarding the guide dog system. I will explore their more tempered stance compared to international perspectives and investigate the dynamics between the opinions of guide dog users and non-users.

In recent years, the emergence of critical Disability studies in Hong Kong has integrated overseas academic research on “ableism”. Drawing from disciplines such as cultural studies, psychology, and sociology, this approach examines how interactions among various Disability and able-bodied groups in Hong Kong shape discussions on Disability and knowledge production across different fields (Wong, Choi Fung, 2014; Ma, Gloria Yuet Kwan and Winnie WS Mak, 2023; Cockain, Alex, 2024).

Building on discussions in these studies, I seek to expand into a new research area at the intersection of Disability and animal studies. By placing the advocacy against guide dogs by animal rights activists in Hong Kong within the context of this ableist discourse production, I aim to deconstruct the utilitarian assumptions behind anti-guide dog system advocacy and the animal-assisted devices narratives in mainstream rehabilitation propaganda. This reevaluation prompts a reconsideration of how seemingly unrelated animal liberation issues can impact the culture of inclusion in Hong Kong.

In recent years, several reports of alleged guide dog abuse have surfaced in Hong Kong media. Since 2021, netizens have captured footage of trainers from the Hong Kong Guide Dogs Service Centre treating dogs harshly during outings. This has led animal rights advocates to criticise the fundamental issues within the guide dog system, introducing the statement of “happiness deprivation”.

In late 2023, a website called “Friend of Animal” (不吃動物的人), featured a post titled “Questioning the Guide Dog System”, written by Loi Man Ho, an MPhil student from the Department of Philosophy in Chinese University of Hong Kong. This post responded to the death of a guide dog named Funny at a Tseung Kwan O shopping mall in October 2023. Wong compiled various online criticisms, highlighting ethical concerns within the guide dog system, claiming that these objections are grounded in “basic facts”, and advocated for an alternative replacement to guide dogs:

“[…] According to the Hong Kong Blind Union, the guide dog’s method of guiding is described as follows: ‘The owner needs to know how to get to their destination first, and then command the guide dog to go straight, turn right, or turn left. During the journey, the guide dog is responsible for preventing the owner from colliding or falling, and guiding them to avoid obstacles due to sudden changes in road conditions.’ This effect contradicts the natural instincts of ordinary dogs, so they must undergo rigorous training to become qualified guide dogs. Specifically, guide dogs are trained to have high self-discipline to complete their tasks without being easily distracted. We are not allowed to interact with guide dogs casually, and they also learn to reject interactions with other people and animals. Therefore, guide dogs have minimal social lives apart from their owners. In addition, guide dogs are trained to control their physiological needs in order to serve their owners. For example, they are trained to relieve themselves on command, rather than based on their own needs. Of course, we can also train pet dogs or children not to relieve themselves randomly, but compared to them, guide dogs are clearly subjected to higher levels of regulation. Lastly, we cannot obtain consent from dogs. Because they cannot speak, they cannot express consent like humans do […]” [1]

We can see Loi Man Ho critique the guide dog system by highlighting that these working dogs undergo rigorous training to serve humans, which distorts their natural physiological needs, such as using the bathroom on command. Loi argues that not all visually impaired individuals need or are suited for guide dogs, and if this system compromises the dogs’ natural behaviour, alternative solutions should be considered.

The origin of this post can be traced back to an incident that occurred a month ago at the Kornhill Plaza in Tseung Kwan O, where a guide dog named Funny tragically passed away due to poisoning. Following the news coverage by Hong Kong Animal Post [2], a large number of netizens began questioning the Hong Kong Seeing Eye Dog Services, which had faced allegations of animal cruelty in the past, for its inadequate protection of service dogs. Some netizens, citing information from insiders, accused some visually impaired individuals of mistreating dogs. There were even claims suggesting that the breeds being bred by these organisations might have hidden genetic issues.

In the Hong Kong Animal Post report, the journalist interviewed animal rights activist Roni Wong who, even before the official cause of Funny’s death was disclosed, raised concerns about the ability of visually impaired individuals to care for dogs. Wong suggested that if the incident had occurred in a private setting rather than a public space, there would have been no one to assist in transporting the dog to a hospital. Unlike the “Questioning the Guide Dog System” post by Loi that I quoted above, the journalist’s response to the news focused more on the guide dog training system and extended to the users of guide dogs, sparking accusations online regarding the capabilities of visually impaired individuals.

The responses to Loi’s post critiquing the system and the comments targeting visually impaired individuals have both been polarised on social media. Many questions were asked as to why the guide dog system is being singled out when there are numerous instances of dogs, such as police dogs, providing public services in society. Guide dog users then argue that such interpretations ignore common knowledge about dogs not being wild animals and that their nature is to interact with humans; training merely nurtures this natural behaviour. On the other hand, animal rights activists supporting these views emphasise their opposition to all systems involving training animals, with guide dogs being just one example, rather than specifically targeting visually impaired individuals. However, these anti-guide dog system sentiments that have spread online have left guide dog users feeling unsettled. Even visually impaired individuals who do not use guide dogs experience a sense of public scrutiny and pressure when images of guide dogs and visually impaired individuals in public spaces are continuously captured, scrutinised, and questioned online.

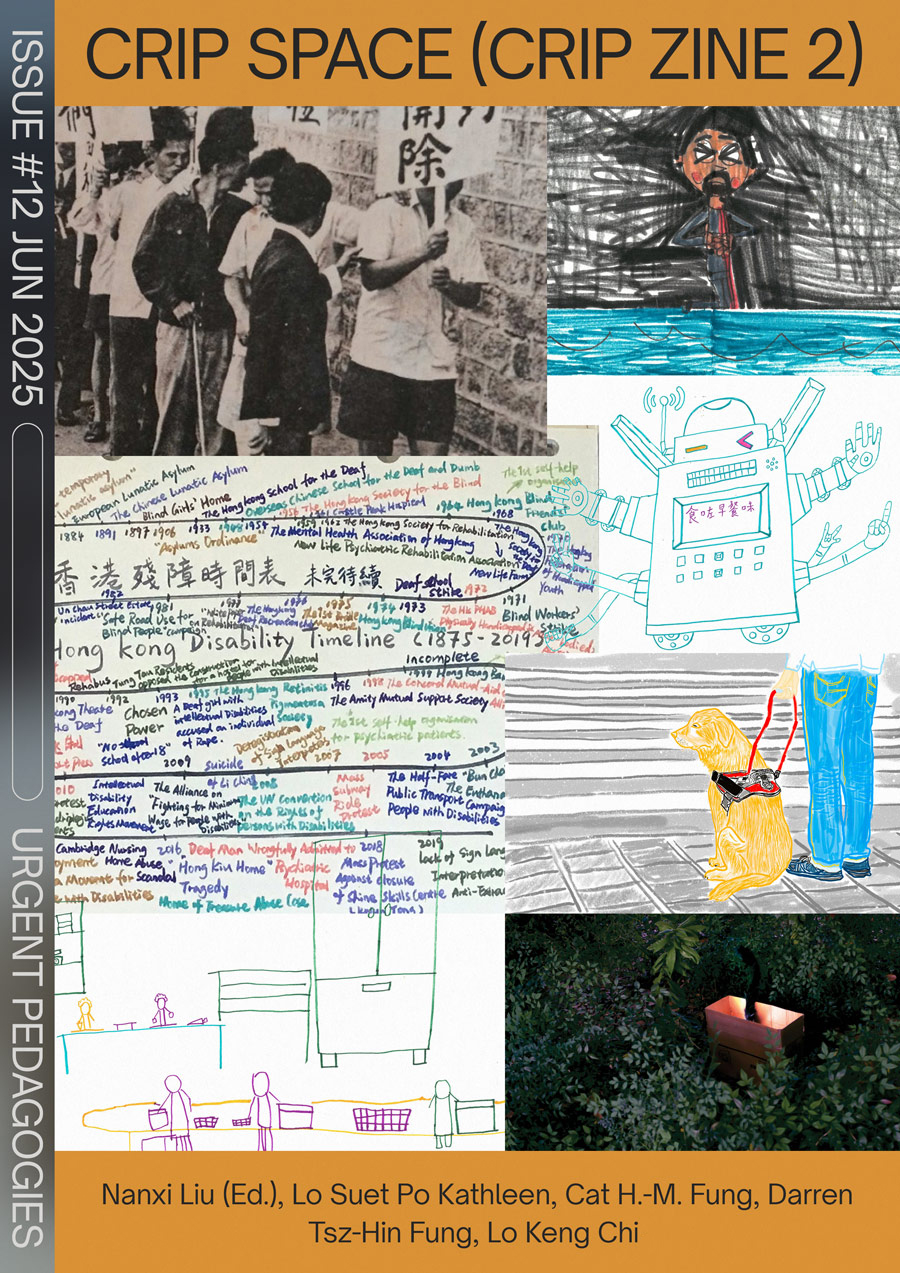

Police and police dogs questioning a person in Hong Kong. Photo by Wong Chiman.

To disprove any bias against visually impaired individuals, a month later, Wong released another lengthy post titled “Do Visually Impaired Individuals Need Guide Dogs?” on his own Facebook account [3] and later on Hong Kong Animal Post. [4] The post aimed to gather and organise data from blind rehabilitation facilities and featured an interview with a visually impaired individual called Ah Sei (阿詩) who does not use a guide dog, in an attempt to validate the anti-guide dog system stance. This effort received support from some members within the visually impaired community.

Reflecting on the context in which this post emerged, it appears that the activist Wong, is advocating for a particular animal rights ideology. His statements and posts aim to mobilise and rationalise his supporters’ targeted actions. Across various media platforms and in response to different criticisms, there are inconsistencies in his arguments, and many real-life complexities are oversimplified. My intention here is not to address each argument in the debate but rather to clarify the animal rights perspective held by these Hong Kong activists who oppose the guide dog system and what exactly the guide dog system they oppose entails.

In the book Domestication and Desire: The Dark History of the Relationship Between Human Beings and Animals, animal ethics researcher Hsieh Hsiao-yang discusses the long-standing focus on the harm caused to various species by domestication throughout human history. The book explores the origins of domestication systems and how hunting, agriculture, capitalism, colonialism, religion, and gender norms have shaped the exploitation of animals, driven by desires constructed by modern society.

The historical crimes of human domestication of animals involve treating them as private property and employing various means of harm and control. How does the colonial history of Hong Kong, with its commodification and abuse of animals, help us trace the domestication history of the guide dog system? Hsieh’s book includes chapters discussing pet dogs, touching on issues such as middle-class fashion, military use, breeding, and genetic modification. Can these historical responsibilities be attributed to the “guide dog system”? Also, can the needs of blind or Disabled individuals for assistance dogs be equated with the royal and commercial exploitation of animals?

The genesis of guide dog services can be traced back to the tumultuous period of World War I, characterised by the widespread use of chemical warfare leading to a significant number of soldiers being afflicted with blindness. The inception of a rehabilitation service aimed to facilitate the honourable reintegration of these valiant white male national figures, who made the ultimate sacrifice for their country, back into society. This form of rehabilitation service, which harnessed the assistance of dogs to aid wounded soldiers, initially emerged in Germany and garnered international recognition. Subsequently, in 1929, dedicated volunteers in the United States spearheaded the introduction and enhancement of this system, culminating in the establishment of the pioneering guide dog training institution, known as Seeing Eye.

It is discernible that the foundational framework of guide dog training is rooted in the ethos of German history, where military canines were instrumental in the rehabilitation of white male servicemen (Pemberton, 2019). However, it is imperative to acknowledge that the role of these erstwhile military dogs diverges significantly from the contemporary function of guide dogs. The early establishment for guide dog training in the United States astutely recognised the incongruence between traditional Western methodologies employed in training military and law enforcement canines and the unique demands posed by visually impaired individuals. The distinctive guiding responsibilities entrusted to guide dogs necessitate an approach distinct from the protective duties assigned to police and military canines. Consequently, the innovative service dog training paradigm—cultivated at the aforementioned guide dog institution Seeing Eye in the United States—eschews the subjugation of animals’ innate instincts, opting instead to underscore the cultivation of mutual trust engendered through sustained playful interaction between humans and canines, as opposed to unilateral mechanistic control.

The responsibilities of guide dogs lie in guiding individuals with visual impairments. Due to the potential for environmental misjudgment stemming from the vision impairment of the blind, training guide dogs cannot adopt the same approach as training police or military canines, where blind obedience is demanded. Absolute compliance from guide dogs to commands issued by the visually impaired could pose risks. For instance, if a blind individual instructs a guide dog to step onto a pedestrian path, the guide dog must exercise its ability to independently assess environmental risks, leading to actions that may appear as “disobeying commands”. This unique ability required by guide dogs was termed “intelligent disobedience” by the guide dog training schools of that era.

Neil Pemberton, a scholar in Disability studies, in his examination of this historical narrative, elucidated that the emphasis on nurturing canine intelligence in guide dog training diverges from the Western white male dominance culture, where controlling conditioned dogs to guide individuals is akin to operating a machine. Instead, the training underscores a profound emotional attachment between the visually impaired and the guide dogs, relying heavily on partnership and cooperation to cultivate the dogs’ adaptability to their surroundings.

This highlights the rigorous nature of the guide dog training process, which not only places significant emphasis on accommodating the unique traits of each dog but also necessitates that visually impaired individuals who rely on guide dogs for assistance undergo a form of training that can be likened to “nurturing”. This involves learning to adapt to the physiological characteristics of the dogs and providing appropriate joy and satisfaction, such as expressing affection by stroking specific parts of the dog’s body to convey warmth—a process that demands meticulous refinement.

However, this does not imply that when the guide dog system is transplanted to Asian countries, this training practice will remain unchanged. Whether it pertains to guide dogs or any rehabilitation system designed to safeguard the rights of individuals with Disabilities, numerous social issues may potentially arise.

While it is true that transplanting the guide dog system to Asian countries may lead to a transformation in training practices, it is essential to recognise that any rehabilitation system aimed at safeguarding the rights of individuals with Disabilities could encounter various social issues.

In Hong Kong, the aim of promoting guide dog services is to enable visually impaired individuals to live in barrier-free environments, fostering independence, confidence, and self-reliance in their daily lives. The timeline for promoting the rights of Disabled individuals varies across different regions, and it was not until the first decade after the millennium that the Hong Kong government began incorporating service dog training systems, rooted in the charitable culture of the United States, into their long-term rehabilitation plans. While providing certain subsidies for basic infrastructure, these initiatives are not permanent funding projects under the Hong Kong government’s Social Welfare Department. Apart from needing to reapply for entry every two to three years with other private funds, a significant amount of time is also devoted to organising numerous charitable fundraising events to sustain operations. Reflecting on the slogans often echoed in the promotion of guide dog services, such as “Guide dogs are not tools but partners of visually impaired individuals”, the role of these service dogs is to enable individuals to “participate in various community activities, expand their life domains, and thereby establish an independent, confident, and dignified life”. [5]

The sociologist Alex Cockain (2017), who previously held a position at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, also traced back the understanding of Disability within the United Nations Convention. He noted that the designation of “Disability” in Hong Kong is neutral, devoid of any specific pejorative connotations. Conversely, the civic identity surrounding “Disability” exhibits considerable ambiguity. Cockain identified a primary reason for this ambiguity as the Hong Kong government’s long-standing tendency to obfuscate many concepts and principles in the Chinese translation of United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Consequently, this has led to differing interpretations by both abled and Disabled individuals regarding the government’s promotion of the Disability Rights Convention. The knowledge concerning the identity of Disabled individuals in Hong Kong, thus derived from varied interpretations by different abled/Disabled entities, has established, as Michel Foucault described, a discursive space in which individuals have the capacity to “form the objects of which they speak”. This space is termed by Cockain as the “shallow inclusion” culture of Hong Kong’s rehabilitation, which he characterises as employing a rhetoric of inclusivity that blurs the distinctions between inclusion and integration.

Another Hong Kong researcher, Wong Choi Fung (2014), also delved into the exploration of terminology related to Disability and impairment. She meticulously organised designations such as “injury Disability” and “Disability”, as well as terms like “injured-abled integration”, which emerged in different historical contexts in Hong Kong during the 1980s and 1990s. Wong also pointed out that various “inclusive” terms simply reflect the effects of neoliberal power infiltration in population governance policies. Reflecting on a series of newspaper articles, media reports, and dramas promoting injured-abled integration, Wong highlighted how the mainstream often views Disability through a lens of pity, perpetuating a self-discriminatory ableism that undermines the self-worth of Disabled individuals.

These critiques focusing on research within Hong Kong’s inclusive culture, contribute to our understanding that while hundreds of thousands of individuals in Hong Kong identify as Disabled, this cultural identity has struggled to transcend the superficial discourse of shallow inclusion. With the introduction of Critical Disability Studies in Hong Kong research, scholars have begun to view the social integration of Disability as a research space that addresses a range of political, theoretical, and practical issues relevant to everyone.

Influenced by scholar Fiona Kumari Campbell’s concept of ableism, researchers now perceive the marginalisation of Disability as an ongoing structural issue intertwined with broader societal and institutional frameworks. By examining the daily lives of Disabled individuals in Hong Kong society, scholars are reevaluating how concepts of normalcy, abnormality, ability, and Disability contribute to a binary linguistic structure and aim to challenge and dismantle everyday epistemic frameworks of Disabilities.

I believe that the stance taken by animal rights activists against the guide dog system overlooks the significant backdrop of Hong Kong’s rehabilitation and inclusive culture that underpins the guide dog system. Furthermore, it fails to provide a comprehensive explanation of how guide dogs have become tools integrated into the daily lives of visually impaired individuals within the rehabilitation system. Ultimately, this narrow perspective allows such animal rights activists to develop discriminatory behaviours and attitudes towards guide dog users.

In Loi Man Ho’s article on the “Friend of Animal” website, he further draws a comparison between guide dogs and the humans who provide the guiding services. He argues that guide dogs evade the labour rights afforded to humans and provides a more detailed discussion on philosophical and ethical topics such as suffering, consent, and verbal expression. This approach of analysis clearly exemplifies a typical utilitarian reasoning logic, firmly asserting that “the training of guide dogs will inevitably harm the interests of the dogs” and appealing to the notion of “impossibility of obtaining consent”, which he argues should lead us to halt such practices.

Around 10 years ago, the first batch of guide dog trainers emerged in Hong Kong. During the initial expansion of this service, I inquired about the application process for obtaining a guide dog and successfully passed the initial interview conducted by the service organisation. However, after considering the nature of my work for the next several years—which would primarily involve writing papers indoors—I found it difficult to share such a monotonous lifestyle with a service dog. Consequently, I decided to postpone my application until after graduation when I could secure a new job.

A few years ago, I received the application form and contemplated whether to submit my application for a guide dog. One day, whilst dining with a friend, we passed by one of the busiest roads adjacent to a housing estate. My friend suddenly exclaimed with excitement:

“Wow! I just saw an advertisement for a guide dog on a bus!”

“What is the advertisement promoting?”

“It seems to be a promotion by the Link…” [6]

This incident may not encapsulate all my reasons, but it was certainly one of the contributing factors that dissuaded me from applying for a guide dog. While I should have been accustomed to the fact that these guide dogs are used as promotional tools by retail developers such as the Link Real Estate Investment Trust, in that moment, I felt a chill in my chest, and the sensation of my intercostal fascia contracting is still vivid in my memory.

Tracing the context of Hong Kong’s guide dog system and its attention from animal rights advocates is largely influenced by the numerous reports and videos of suspected dog abuse that have surfaced online in recent years. However, unlike these “sighted” animal rights advocates, I cannot be deeply moved by viewing videos of guide dogs being abused during their training. Furthermore, I do not blindly accept the various arguments for and against the use of guide dogs from both users and non-users.

I have never applied for a working dog to be my companion, not out of pity for the suffering of guide dogs, but because I have never been able to clarify what exactly is meant by the notion of being in a “pitiful” position. Since the age of 16, when my vision began to deteriorate significantly, I have continually grappled with the image of being an inspirational figure among relatives, family, and friends. This struggle intensified as I spent over eight years gaining admission to The University of Hong Kong, becoming one of the exemplary Disabled students in the educational sector. At every moment, I have felt restless due to this identity as a tool of various systems. Perhaps my conditioning within the culture of integration in Hong Kong has not been sufficient, preventing me from attaining the high level of self-discipline required to fulfil the paramount tasks of “promotion” and “fundraising” like other resilient warriors and educational role models in society. Consequently, nearing the age of knowing my fate, I remain in university, unable to extricate myself from the educational system and become a “working person”. I realise that even if I were to be matched with a working dog, I would still struggle to understand how I could live like a “normal person”.

In my life, guide dogs have often been portrayed by the media as tools for building the charitable brand image of organisations. This is not due to any ethical issues inherent in their training systems, but rather because they reshape a desire that I find difficult to share under the guise of rehabilitation and charity. This desire stems from narratives that tell inspirational stories of blind individuals overcoming adversity. Calling guide dogs “tools” aligns them with Sunaura Taylor’s concept of “animal prosthetics”. The media often portrays the human-animal bond as loyal companionship, but this overlooks the functional reality. These portrayals remain within a melodramatic framework that emphasises the dog’s traits, hoping to show Disabled individuals overcoming their limitations and becoming “normal”. The quotation marks around “normal” highlight the problematic societal expectation of conformity.

In animal rights activist Roni Wong’s article, distinct perspectives on the guide dog system held by the visually impaired community are indeed outlined. However, he cites an article titled “Nikki’s Guide Dog Life”, written by a guide dog user from Taiwan, and compares it with the opinions of his interviewees, suggesting that one interviewee’s views helps refute the article’s arguments. He posits that dogs have become tools for the blind due to the inability of humans and dogs to mutually care for one another, as blind individuals cannot comprehend the “dog nature” that enjoys sniffing and licking the ground.

Under this inference, the binary opposition of happiness and suffering becomes the battleground for sighted animal rights advocates and blind guide dog users competing for prominence on contemporary social media platforms. When Wong interprets this interviewee’s statement as concluding that guide dogs experience more suffering than happiness, he completely overlooks that the blind interviewee, who does not use a guide dog, emphasised a criterion of ability superiority inherent in the training system for guide dogs. Lacking long-term experience living with guide dogs, Ah Sei merely expresses concern and sympathy for them, fearing that “we, being blind, often worry about accidentally stepping on their paws”, while also showing concern for the fate of those dogs that are “ultimately disqualified”.

The measurement of happiness and suffering is derived from famous Australian philosopher Peter Singer’s utilitarian animal liberation theory, which maintains the bias held by early Western environmental theorists that domesticated animals, such as pets, lack the survival competitiveness of wild animals. Their docility is seen as a form of foolishness and an original sin of anthropocentrism. Consequently, Taylor refers to this hierarchical distinction between wild and domesticated animals as a form of ableist assumption akin to Disability discrimination. Such assumptions often arise from human anxiety about their dependency on nonhuman entities, as this dependency illustrates an imbalanced ethical relationship between humans and animals. It perpetually instils a sense of compelled fear, obscuring the shared bodily vulnerability between humans and animals. Furthermore, it fails to recognise how this vulnerability can help transcend the epistemological limitations of ableism and speciesism, providing a broader understanding of interdependence in the agenda for animal liberation.

From Wong’s critiques of the guide dog system, I perceive that this anti-guide dog initiative not only questions the insufficient transparency of guide dog service organisations, but also highlights the capabilities of blind individuals. It neglects to consider more structural issues that lead to the deaths of guide dogs and other animals, as well as the broader environmental pollution problems. A review of news reports from one or two weeks before and after the poisoning incident in Hong Kong reveals other cases of animal poisoning in public spaces. Many believe that the true cause of the guide dog’s death was the indiscriminate placement of poison in the community. However, the declarations and interviews from those opposing guide dogs have directed a segment of animal rights supporters to focus on the guide dog system and to question the abilities of visually impaired individuals to care for animals. This not only ignores the environmental toxicity issues that could jointly concern Disability and animal rights but also fails to extend the reflections triggered by recent dog abuse incidents to the rehabilitation charity industry and consumer culture that I have long been concerned about.

Although we cannot expect animal rights advocates to fully immerse themselves in and understand the lived experiences of Disabled individuals like sociologists or anthropologists do, we must also critically examine how the seemingly mild anti-guide dog initiatives proposed by these advocates harbour what Cockain refers to as an epistemic invalidation present in everyday life in Hong Kong. This ableist form of knowledge production obscures the first-hand experiences and voices of guide dog users and non-users like myself, as the mainstream social media propagates images of animal abuse, assuming that all animals are helplessly suffering and that only a return to the wild can provide salvation, thus masking a form of superior knowledge held by able-bodied individuals.

This situation prevents Wong’s article from exploring any connections between Disability and animal rights movements, actively provoking conflicts between blind non-guide dog users—like myself—and guide dog users to rationalise the discriminatory remarks made by their supporters. However, this differentiation between users and non-users is fundamentally based on a binary understanding of whether guide dogs experience “happiness” or “suffering”. Logically, the long-term coexistence of guide dog users and their dogs, along with the positive attachment relationships they must establish, ought to represent a shared daily experience of human-animal coexistence. Yet, this daily cognitive experience of guide dog users is temporarily erased within this binary framework of animal rights, ultimately leaving the ethical issues between guide dogs and blind users to be understood within the superficial framework of mainstream rehabilitation charity promotion.

Taylor’s critical reformation on the agenda of Disability and animal liberation, redirected our focus towards the interplay of Disability and animals, exploring how to no longer view animals simply as voiceless victims. This approach, centred around concepts of access intimacy between human and animal, opened up dimensions of our analysis beyond the desire of domestication.

Since the emergence of discriminatory remarks against guide dog users, I have continued discussions with fellow activists concerned about environmental issues and organised exchange activities with visually impaired friends who care about these events. In these meetings, there were individuals like myself who, due to personal reasons, do not wish to apply for a guide dog, and users who expressed anger at the distorted claims made by animal rights advocates. A young visually impaired member, who had once cared about animal rights, heard a university professor with an animal rights stance state that guide dogs violate nature; nonetheless, he still believed that applying for a guide dog held intrinsic value. A vegetarian friend noted that many older non-users believe that Hong Kong is unsuitable for guide dogs, to which she confidently replied, “Yes, Hong Kong may also be unsuitable for human beings”.

Like Disabled communities elsewhere, the visually impaired community in Hong Kong possesses diverse opinions on any issue, influenced by varying degrees of blindness or low vision, congenital or acquired conditions, as well as gender and age differences. Since I joined a visually impaired organisation in the late 1990s, I have heard countless blind predecessors explain that Hong Kong’s environment is not conducive to the use of guide dogs; however, around a decade ago, this service began to be widely promoted in Hong Kong.

Do we still need to ask who is right and who is wrong? Or have we always had blind spots in our understanding of the diverse voices within the visually impaired community?

The debate in Hong Kong surrounding guide dogs, centres on a utilitarian assessment of animal welfare. Animal rights advocates view guide dog training as oppressive, arguing that domestication itself represents a form of Disability, implying that both blind individuals and guide dogs are inherently incapacitated. They believe that neither party is capable of ensuring the other’s safety. This perspective, however, is flawed; it unfairly scapegoats one community while ignoring the complexities of historical injustices related to animal domestication. Simply returning all domesticated animals to the wild would not erase these historical wrongs.

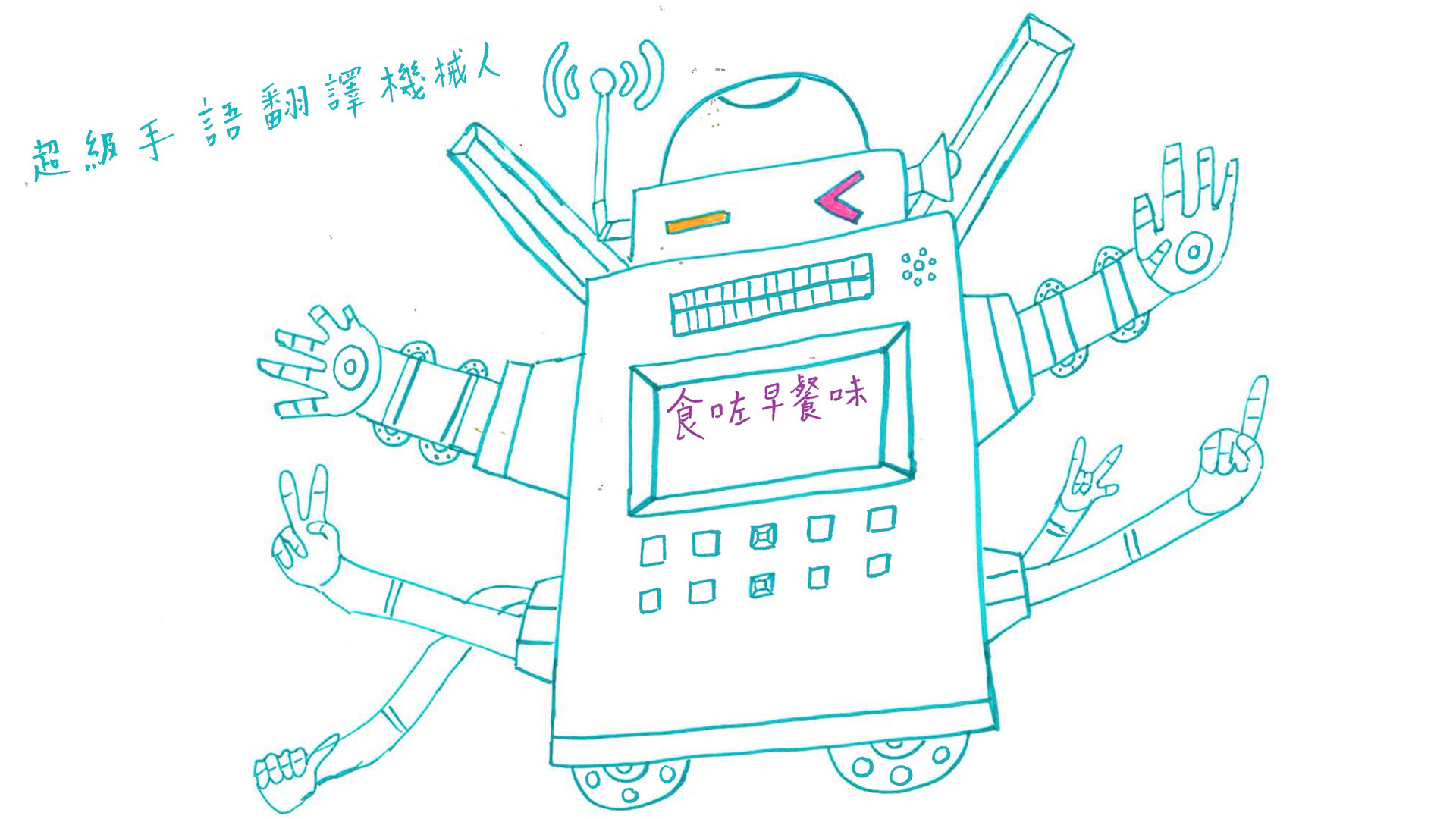

Therefore, a more moderate approach is advocated, focusing on gradually replacing guide dogs with new assistive technologies, such as robotic guide dogs. This transition, however, should be led by the rehabilitation sector and guide dog users themselves, with continued pressure from animal rights advocates to ensure the process is ethical and effective. The development and implementation of effective robotic alternatives are crucial to achieving a humane solution that respects both the needs of visually impaired individuals and the welfare of animals. This approach acknowledges the value of guide dogs while exploring alternatives that could potentially alleviate ethical concerns. Further research and development in robotic guide dog technology are needed to ensure that these devices are reliable, safe, and truly capable of replacing the invaluable assistance currently provided by guide dogs.

This article attempts to extend critical Disability studies in Hong Kong, which increasingly emphasises ableism research, by viewing online animal rights discourse rooted in Western animal liberation theory as a knowledge production process that promotes the opposition between Disabled and non-disabled individuals and causes fragmentation within the visually impaired community. I do not wish to base any moral evaluations on a single stance regarding Disability or animal rights; rather, I aim to highlight how online discriminatory remarks against blind individuals exist within a research domain that intersects Disability and animal rights issues. I hope that both Critical Animal Studies and Critical Disability Studies can start from the blind spots of these online discourses to: explore more insightful research on the history of the domestication of dogs in Hong Kong; the intimate access relationships between blind individuals and guide dogs; and the development of assistive technologies for travel amongst visually impaired and blind individuals. Furthermore, I advocate for a more balanced and in-depth discussion in future research and public discourse regarding the criticisms of the guide dog system in Hong Kong.

Acknowledgments: I would like to thank a Facebook friend for drawing my attention to the strong sense of ableism in the posts of an animal rights advocate, which inspired me to undertake this research. I also appreciate the friends in the Care Work Reading Group for their feedback and recommendations for some of the references used in this article. Additionally, I thank the Hong Kong Blind Union for organising discussions on animal rights, allowing me to hear different perspectives from visually impaired friends who use and do not use guide dogs. Finally, I extend my gratitude to the faculty and students at the Disability Equality Lab at UC Berkeley for their suggestions on revising the article, and reminding me to refocus on the context of rehabilitation and Disability culture discussions in Hong Kong.

Bibliography

Cockain, Alex. Learning Disability and Everyday Life. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2024.

Cockain, Alex. Shallow Inclusion (or Integration) and Deep Exclusion: En-Dis-Abling Identities through Government Webpages in Hong Kong. Social Inclusion 6.2 (2018), 1-11.

Hsieh, Hsiao-yang. Domestication and Desire: A Dark History of Human-Animal Relations. Hong Kong: InPress, 2019.

Ma, Gloria Yuet Kwan, and Winnie WS Mak. Maintenance of Ableist Society for Wheelchair Users: Roles of Medical Model of Disability and Witnessed Negotiation for Accessibility. Disability & Society (2023): 1-26.

Kheel, Marti. Nature Ethics: An Ecofeminist Perspective. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008.

Pemberton, Neil. Cocreating Guide Dog Partnerships: Dog Training and Interdependence in 1930s America, Bioethics Quarterly vol. 45 iss. 1 (2019), 45-92.

Putnam, Peter Brock. Love in the Lead: the Fifty-Year Miracle of the Seeing Eye Dog. New York: Dutton, 1979.

Taylor, Sunaura. Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation. New York: London, The New Press, 2017.

Wlodarczyk, Justyna. Genealogy of Obedience: Reading North American Pet Dog Training Literature, 1850s-2000s. Brill: Leiden, 2018.

Wong, Choi Fung. Forging a New Disability/Gender Culture in Hong Kong—Establish Disabled Feminism. CUHK electronic theses & dissertations collection, Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2014.

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

The original text is in Chinese and posted on https://www.frdofanimal.org/post/%E5%80%BC%E5%BE%97%E8%B3%AA%E7%96%91%E7%9A%84%E5%B0%8E%E7%9B%B2%E7%8A%AC%E5%88%B6%E5%BA%A6 (accessed 26 Mar 2025). The English version is translated by author.

2.

https://hkanimalpost.com/2023/11/13/11133/ (accessed 26 Mar 2025)

3.

https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=10160515847432772&set=a.457559132771 (accessed 26 Mar 2025)

4.

https://hkanimalpost.com/2023/12/16/12161-5/ (accessed 26 Mar 2025)

5.

https://www.eoc.org.hk/en/Articles/Detail/740 (accessed 26 Mar 2025) Translated by the author.

6.

Established in 2005, Link REIT, originally known as Link Management, is the largest real estate investment trust (REIT) in Hong Kong, with a focus on managing retail and commercial properties. It was initially formed from public rental housing and commercial properties owned by the Hong Kong government. The company has faced criticism from society for increasing rents, which impacts the survival of small businesses, leading to excessive commercialisation that severely affects the lives of grassroots communities. In response, the management frequently promotes charitable initiatives supporting rehabilitation to improve its public image.

is a visually impaired individual, poet, and cultural critic. He is currently a PhD candidate in the Department of Cultural and Religious Studies at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, focusing his research on disability and contemporary Chinese culture.