Endangered learning environments and the problem of “Safe Space”

Tom Holert

CATEGORY

“Embracing paradoxical binaries to me seems a valid method to avoid the flattening effects of certain interpellations of ‘urgency’.”

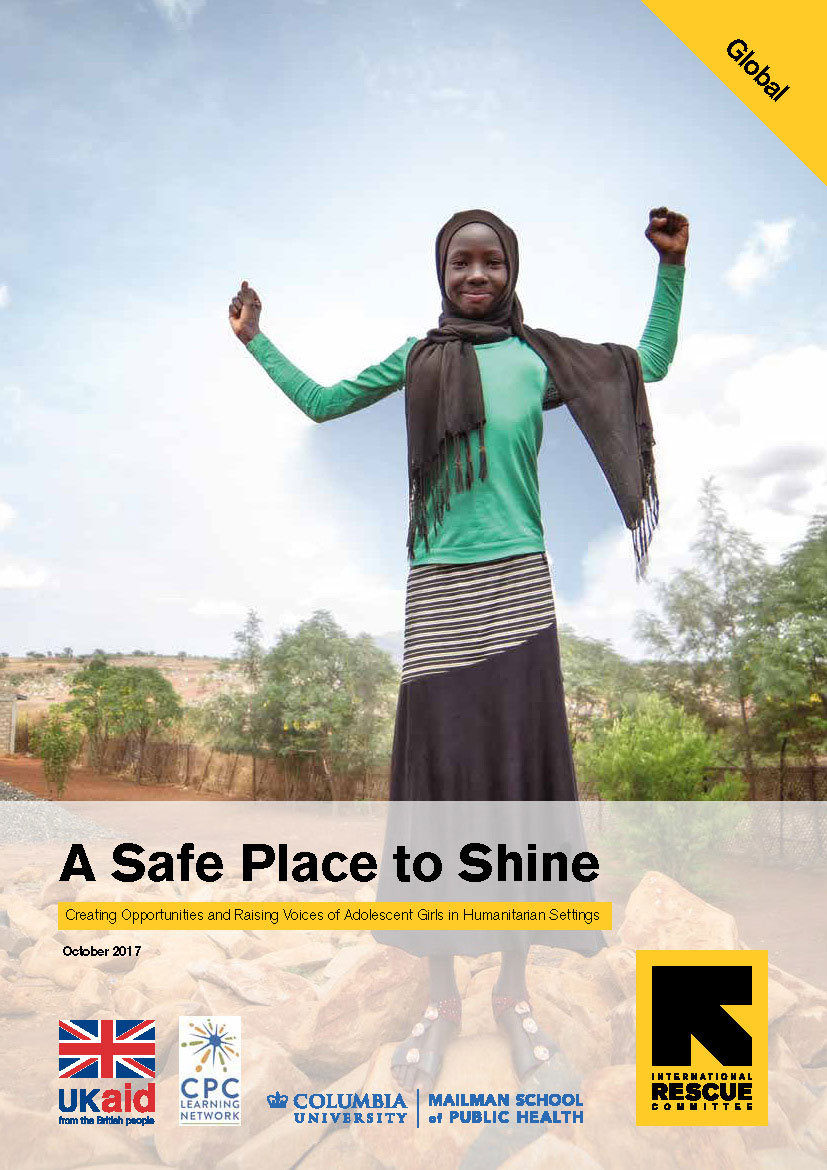

The cover of the October 2017 report A Safe Place to Shine: Creating Opportunities and Raising Voices of Adolescent Girls in Humanitarian Settings by the Violence Prevention and Response Unit of the International Rescue Committee shows a photograph of the 14-year old Alewya (no surname provided), from South Sudan, who at the time lived in Bombassi refugee camp, in Ethiopia. The copytext on the flipside of the cover page has the following to say about (and by) the girl who smiles toward the photographer (Meredith Hutchison), raising her two arms, her hands formed into fists. “To pursue her dream of becoming a teacher, [Alewya] attends life skills sessions run by the IRC in girl-only safe spaces. ‘Adolescent girls need to come to the safe space to learn and to make friends,’ she says.”

October 2017 report A Safe Place to Shine: Creating Opportunities and Raising Voices of Adolescent Girls in Humanitarian Settings by the Violence Prevention and Response Unit of the International Rescue Committee. Photo: Meredith Hutchison.

The short quote alludes to a peculiar geography (or topology) of education and protection that has been put in place in refugee camps such as Bombassi. In order for Alewya to pursue her “dream of becoming a teacher”, she attends “life skills sessions” that are offered in “girl-only safe spaces.” The latter exist apart from schools, although they are supposed to fulfil the pedagogical and psychological function of providing what the World Health Organization in 1999 has defined as “a group of psychosocial competencies and interpersonal skills that help people make informed decisions, solve problems, think critically and creatively, communicate effectively, build healthy relationships, empathize with others, and cope with and manage their lives in a healthy and productive manner.“ [1]

In this short essay I aim to provide a context for Alewya’s assertion on the relation between education, sociability and the existence of a “safe space,” in particular for young female refugees, but arguably, to a similar extent, for other vulnerable groups among fugitive and migrant populations. The intention is to understand how policies of “protection” and “education”, with their underlying ideologies and beliefs of resilience held in the realms of humanitarian-educational administration, migration management and governmental politics affect the conceptualizations as well as the on-the-ground realities and spatialities of educational livelihoods.

Educational concerns in situations of emergency and duress are usually voiced in a language of urgency. However, the urgency invoked and defined by the educational-humanitarian-security complex certainly differs from the urgency addressed in the title of the project Urgent Pedagogies. Whereas the latter, as I read it, indicates the necessity of—and demand for—change, transformation, and ultimately improvement (of social justice, of structures of power and hegemony, of ways of living) by way of education (inadvertently touching on the etymology of the Latin educare—to rear, to bring up), the former emphasizes the urgency of education primarily in the interest of security and control (while presumably speaking in the interests of the vulnerable).

The meaning of education is (and has always been) highly contested. Education’s existence seems inevitable and also necessary, but here the agreement also ends. However, the “right to education” is seen as undisputable, in particular when it comes to refugees. Article 22 of the 1951 UN Convention, relating to the Status of Refugees, specifies the right to education for all children, including refugees. Later UN decrees on refugees regulate their “access to education,” involving their ability to enrol in school and to continue one’s studies through to the end of a given level. The United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees (UNHCR) thus aims to ensure “that schools are safe learning environments for refugee children,“ as well as “the right to education for all people of concern to UNHCR by achieving universal primary education and creating increased opportunities for post-primary education (secondary, vocational training, non-formal and adult education) with special focus on girls, urban, and protracted situations.”[2]

If the right to education is based, at least on the level of human rights advocacy and diplomacy, on a seemingly broad, global consensus, the same appears to be true of the discourse on the spatial and safety affordances of education. “School safety” has advanced into one of the major shared concerns for international organizations such as the UN agencies UNHCR, UNWRA, UNESCO and UNICEF, states and supranational governmental bodies (such as the EU), as well as of globally operating NGOs such as Save the Children, Education Cannot Wait, riskRED, Global Giving, CFBT Education Trust, or World Vision.

This conjuncture without a doubt relates directly to the increasing violations of the spaces of education, an upsurge of military uses of educational facilities and, even more, to the countless military attacks on schools in various parts of the world. However, the weaponization and victimization of students, teachers, other staff, and school buildings in areas of imminent military conflict or endless low intensity wars not only entail dead and traumatized bodies, while often destroying the fabric of entire communities, but also yield in the production of developmental, and arguably neocolonial systems of aid, equipped with a discourse on resilience and “life skills” that relies on the material and visual evidence of the situation itself.

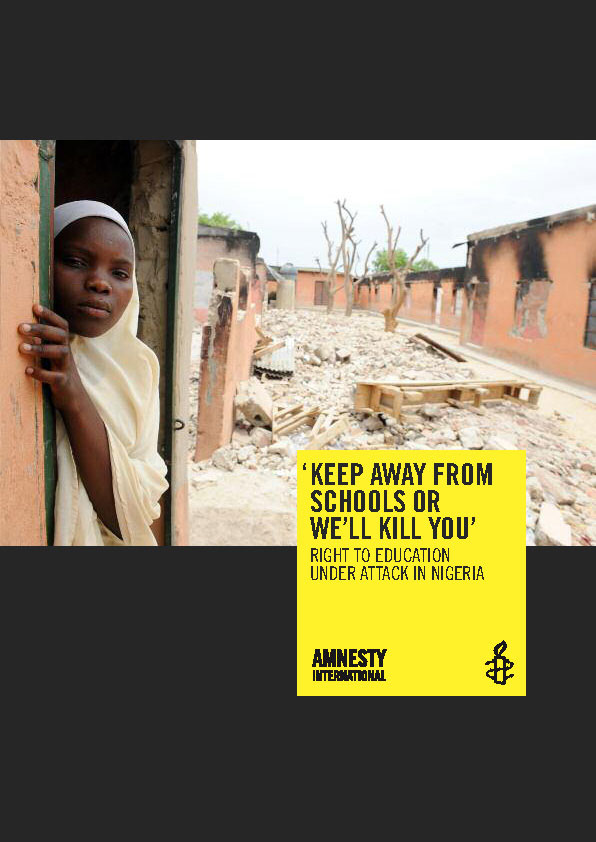

Amnesty International, cover of a report on the destructions of schools and the killings of teachers by Boko Haram militia in northern Nigeria since early 2012 (London, October 2013); the caption of the photograph (by Pius Utomi Ekpei), made in May 2012, reads: “A pupil stands in a burned-out classroom of a school in Maiduguri, Borno state. Many schools in northeastern Nigeria have been destroyed and forced to close as a result of attacks on school children, teachers and buildings.“

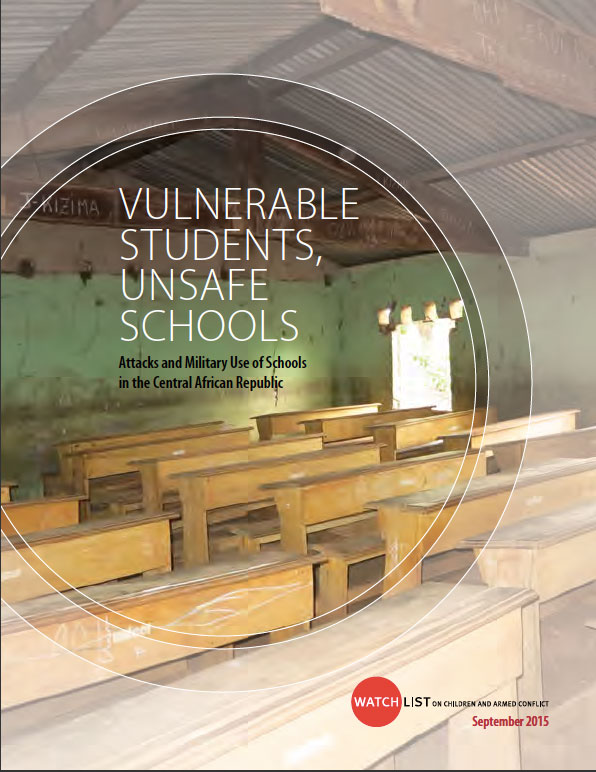

Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict report on attacks on schools in the Central African Republic (CAR) since December 2012 (New York 2015); the cover photograph (by Janine Morna) shows a classroom in a school in the CAR that was looted by civilians and possibly armed groups, as well as used by international peacekeeping forces in 2014.

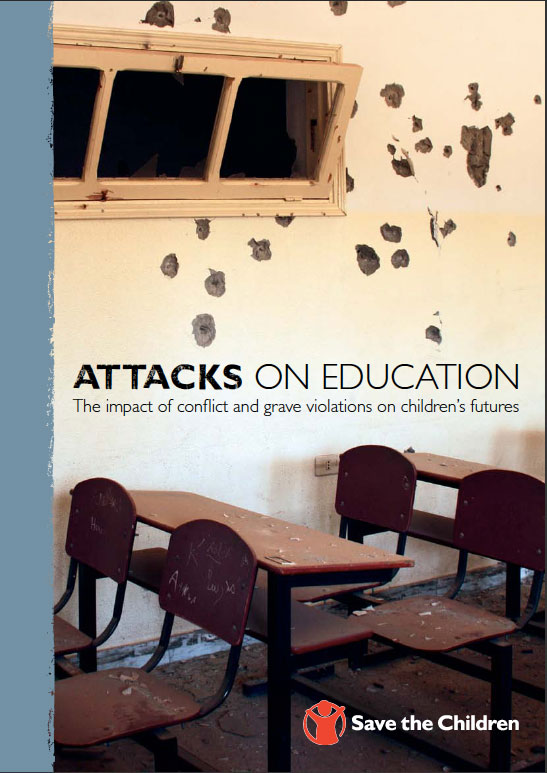

Report of The Save the Children Fund, written by Elin Martinez (London 2013), addressing “attacks on education” in the Global South more generally; the cover photo (by Jenn Warren) depicts bullet holes in the wall of a classroom in Libya (no date).

For a long time, and more systematically since the 1990s, human rights actors, and more recently primarily NGOs (that “are increasingly involved in normative International Humanitarian Law [IHL] development“)[3] have been busy creating awareness (and thus, by default) promoting the issue of unsafe educational environments, particularly (but not exclusively) in areas of the Global South stricken by military conflict, ecological disasters and the ensuing internal displacement and cross-border migration of people. Notably, the problem of school violence and safety in countries such as the United States tends to be researched and discussed apart from the violence directed against schools in countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo or Somalia (where local knowledge about assaults on sites of education and care by far exceeds that of international monitoring agencies).[4] The mass shootings in American schools certainly follow different schemes and patterns than the demolition inflicted by military force elsewhere. However, the deadly outcomes, traumatizations of survivors and effects on the planning, design and management of schools and other sites of education more than invite translocal comparison.[5] Such comparison, however, should not confine itself to academic research but join efforts to arrive at a geopolitical mapping of violence and counter-violence measures that contribute to policies that do not continue to treat cases of violence in isolation and instead read them as incidents within a global economy of violence and geographies of power.[6] As criminal justice scholar Lizbet Simmons observed with regard to the American school system, once “disciplinary strategies expand in the public school landscape, with armed guards, security cameras, metal detectors, and identification practices, there is a need to trace this emergence and to situate these strategies within embedded power relations.[7]”

This said, it is also not entirely clear what determines the success or the failure of a given “protective” learning environment—material or immaterial— to begin with. Even less which definitions and norms of learning would provide the categories for any such evaluation. Often deployed in loose and metaphorical manner, concepts like “space” or “environment” are nonetheless expected to operate in a distinct, unequivocal fashion in relation to categories such as “learning” or “pedagogy.” But this spatiality of education is not simply considered in descriptive, but frequently rendered in ontological terms. In these cases, space and learning are seen as inseparable, or rather, as two parts of a transcendental entity.

However, the very characteristic of this inseparability remains a matter of speculation and experimentation without end. “There is agreement from all parties that a school’s physical plant should mirror its educational philosophy, but the methods for achieving isomorphism are elusive,” the psychologist Robert Sommer noted in 1969.[8] Sommer, although somewhat underappreciated today, remains a resourceful thinker of spatial behavior (and the behavior of spaces). After years of researching the space of the school as an educational and behavioral factor, he frankly admitted his ignorance and the necessity to better understand the distributive spatiality and the multiple—experiential, social, cultural and cognitive—dimensions of learning: “If we know little about what goes on inside classrooms, we know even less about what happens between classes, after class in school clubs, and to a student who does his homework as the radio on his dresser blares away. To understand the institutionalized learning process requires us to deal with a complex ecosystem that includes the community, the school building, as well as the classroom.”[9]

More than fifty years later, insights into “hidden” curricula, “extramural” pedagogies, “informal” ways of learning and non-, or para-institutional modes of knowledge production have grown significantly, not only in the educationalist and pedagogical disciplines. An entire, globally networked field of critical cultural and political practices is now based on notions of self-organized education, radical teaching, consciousness raising, decolonial unlearning, black study, etc.

Cover of a 2013 publication on gender and school violence by researchers working for The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; the image (by Scott Wallace) shows a classroom in Mauchak Scout High School in Gazipur, Bangladesh (neither dates nor names provided).

A UNICEF and USAID supported report based on data collected during a nationwide safety assessment of schools and pre-schools in Kyrgyzstan conducted within the “Reducing the Disaster Vulnerability of Children in Kyrgyzstan” project from May 2012 to January 2013; the photograph on the cover is uncredited.

Save Schools in Safe Territories, a document published in 2008, was produced within the framework of The European Commission Humanitarian Aid department’s Disaster Preparedness Programme (DIPECHO) project “Strengthening Local Risk Management in the Educational Sector in Central America”; the cover photo (no date, no name provided) was taken by Gustavo Wilches-Chaux.

This 2015 manual on community-based “safer school construction,” the result of a year-long global consultation process with construction specialists and development practitioners, was funded by the Global Facility of Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) and managed by Save the Children. It is involved in community-based approaches to safer school construction. The cover image (no place, no date, no names) was made by the Manila-based photojournalist Veejay Villafranca.

Cover of the 2009 “Declaration on Schools as Safe Sanctuaries, issued by Education International (representing 30 million teachers and education workers) and which demanded that schoolsbe respected and protected as zones of peace.“ The photograph by star photographer Emilio Morenatti shows girls from the Bajur tribal region in a school supported by UNICEF at the Katcha Garhi camp in Peshawar, Pakistan, on October 23, 2008.

Not much of these developments have reached the discursive and practical realm of humanitarian interventionism and international NGO thinking. The above selection of cover pages of reports and manuals produced to ensure the “safety” of schools in places of conflict and disaster displays the very kind of gazes and perspectives on learners favored by these agencies (and their art departments). Traces of viewing children and youth differently, that is, beyond their vulnerability and the task to educate them in “safe” environments, as subjects of their own social agendas, epistemologies, and geographies, are scarce if not entirely absent.

The matter becomes particularly complex and problematic when “safety,” “security,” and “protection” are relayed by the conceptual framework of the “learning space” or “learning environment.” For, by definition, the subjects in need of protection have to be individuals and groups identified as “vulnerable” in order for a normative articulation of space, safety and learning to gain sense. But who defines and allocates the attribution of “vulnerability”? Who is calling themselves a victim of violence and abuse (and who finds such designation inacceptable, and for what reasons)? Who is being classified as “vulnerable” by others (and who refuses such identification and classification, as long as it is not self-directed)? Who are the perpetrators of the space of learning to be kept away or defeated (in whose name)? And who is entitled to claim for themselves the role of protector (and provider) of the very “safe space” where learning and making friends, as Alewaya is hoping for, may actually take place?

In a certain perspective, which is largely rooted in the tradition and profession of architecture, the protection required for (and demanded by) the vulnerable finds its material-conceptual solution in spaces or environments that are designed to function as physical envelopes or containers. In this case the protection would manifest itself in walls, fences, barricades, metal-grilled windows, etc., that is in the creation of physical structures that shelter and protect those inside from the violence coming from the outside, whereas the violence committed inside the school space has to be prevented by way of pedagogical skills, social “climate,” cultural values and legal norms (and to be enforced by either the inhabitants and users of the school space or by some kind of police).

In a 2013 report on the attacks on schools in northern Nigeria (most of which being burned down) by Boko Haram—probably the only terrorist movement expressly based on a violent, vaguely post-colonial critique of education (Boko Haram translates as “Western education is forbidden”) —,[10] Amnesty International made the following recommendations to state governments that pertain to issues of staff and security, but also directly to the question of the recuperation, maintenance and securing of the physical space of the school:

“• Provide adequate security to prevent attacks on school buildings, teachers and school children in the state. If police or armed forces are engaged for security, their presence within the grounds or buildings of the school should be avoided to avoid further endangering the students and disrupting the learning environment.

• Immediately renovate and rebuild all schools damaged or destroyed in the state as a result of the violence and ensure that they are provided with adequate teaching staff and other resources in order that children’s access to education can be resumed as quickly and smoothly as possible.

• Ensure that re-opened schools are subject to regular inspection to ensure that standards are being maintained.”[11]

Another manual of “school safety” (attending to the “attacks on schools” in the Central African Republic) recommends:

“• Improving the physical infrastructure of schools through building walls around the perimeter of the schools, installing security bars across windows, and providing locks for classroom and office doors.

• Hiring civilian guards to protect schools, or building directors’ and teachers’ quarters on school premises, provided it does not expose them to unnecessary risk, to deter theft.

• Organizing students, in collaboration with parents, to travel to school in small groups.

• Developing emergency preparedness plans in close consultation with parents and child protection networks in the community.

• Integrating child protection programming into education programming, particularly to address children’s psychological needs and helping to promote the perception of school as a safe place.”[12]

The weaponization of schools and education by military actors in conflict zones is, by default, answered with the hardly cloaked militarization of the schools by those attempting to define and facilitate means of protecting students and staff from the attacks. For readers familiar with the discourse and history of urban-architectural notions such as “defensible space,” dating back to the early 1970s and urban planner Oscar Newman’s influential book of the same title, the language used here may at times recall that of Newman himself or his avid adept C. Ray Jeffery‘s 1971 Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design, the actualization and institutionalization of which as CPTED began in the mid-1990s.[13] CPTED prescribes principles such as “natural surveillance,” “access management,” “territoriality,” “physical maintenance,” and “order maintenance,” which, when applied to a school context, shall contribute to a decrease of delinquent behavior, that is of “school violence.”

The three basic CPTED strategies to be deployed are characterized as “controlling access,” “increasing opportunities for casual surveillance,” and “promoting a sense of ownership.” The criminologist and law enforcement dimension is hardwired to this discourse, while architects and designers are enlisted to serve their traditional disciplinary functions as well as to provide more contemporary features in order to nudge behavior. Studies from this area of security-related psychological research have demonstrated that “school illumination” (sufficient lighting, no dark areas in cafeterias, hallways, stairwells, etc.), like “natural surveillance audit,” potentially prevents unruliness, violent acts, and vandalism. But the same studies also underline that a school’s physical architecture is to be distinguished from (or put in relation to) the users’ perception of the “school environment” which in the respective scholarship is crucially understood as an immaterial, atmospheric, social, and psychological category and quality: “Thus, improving the design of school campuses may lead to greater safety perceptions among students, but only when students notice environmental factors and interpret them in a way that changes their attitudes and perspectives in positive ways.“[14]

I have spent some time with these interventions at the interface of education and securitization because the existential necessity of a “safe space,” introduced by Alewya in the beginning, and the conceptual and material approaches applied to ensure such an environment of psychological comfort and protection from violence (of any kind), can hardly be wrought entirely from criminalist thinking. Reading the numerous (and often disturbingly glossy) reports and brochures on violence and education in refugee camps and sites of emergency (as well as on the situation of migrants and refugees in the intermediary heterotopia between immigration in and expulsion from “receiving” countries, searching for protection and occasions to socialize and learn), I encountered a language that routinely invokes tropes of securitization and crisis management in educational matters rather than one that would attend to (and facilitate a policy that actively addresses) the needs, interests, experiences, and autonomy of learners.

For one, this literature, which has obvious prescriptive functions, could benefit from a distinction made between “security” and “safety” by the urban theorist Peter Marcuse in an article on the threat of terrorism after 9/11:

“• Security is the perceived protection from danger

• Insecurity is anxiety about perceived lack of protection against danger

• Safety is protection from danger

• Danger is the risk of harm”[15]

However, as much the attempt to differentiate between perceptions, affects and the imminent probability of physical violence may contribute to a critique of the antidemocratic and racializing discourse of securitization, it underestimates the role that perceptions and affects have played in the building of politics of identity and solidarity centered on the notion of the “safe space.” Without going into the details of the origins and histories of the term in the gendered geographies of feminist and LGBTQ struggles since the 1970s, it is interesting to note that in the pursuit of safety by minorities, the mid-term result can be security or securitization (something that happened with the “gay neighborhoods” in New York or San Francisco which over time developed from impoverished, endangered spaces into expensive zones of highly policed gentrification).[16] The perception of safety and unsafety, a crucial incentive to organize and mobilize around issues of threat and violence against vulnerable and marginalized people, can become a force of spatial politics and may end up initiating the social production of space in terms of community building and reciprocal watchfulness; it can, however, also turn into a driver of fortified enclosure and gatekeeping.

Thus critical geographers Heather Rosenfeld and Elsa Noterman (who publish under the alias The Roestone Collective) have argued that “safe spaces should be understood not through static and acontextual notions of ‘safe’ or ‘unsafe,’ but rather through the relational work of cultivating them.”[17] Speaking from and for the experiences and livelihoods of marginalized people in the city and on the campus, Rosenfeld and Noterman, among other things, discuss the pitfalls of separatist, exclusionary strategies deployed in the intent to produce safety for such groups. For safe space, in their view, is inherently paradoxical, “not merely an attempt to create an abstract sense of equality, to smooth over differences, or to step outside of and ignore the dangers and injustices of the world. The work of producing safe space entails continually facing, negotiating, and embracing paradoxical binaries: safety/danger, inclusivity/exclusivity, public/private, and so forth.”[18]

Embracing paradoxical binaries to me seems a valid method to avoid the flattening effects of certain interpellations of “urgency.” If “safe space” is used to build (and care for) the very kind of relationalities emphasized by Rosenfeld and Noterman, in contrast to the fortifying and securitizing of the physical (and arguably the digital) environments of learning, a deeply detailed and precise reading of every situation in question is required. “Safe space” is continuously and increasingly constructed from various and often antagonistic actors at the same time. It is thus constantly contested. Imparted from above, increasingly by way of a “pop-up governance,” comprising “abruptly introduced and retractable set of governance mechanisms responding to the situation at hand,”[19] these constructions, like in the case of migrants and refugees in places such as Athens, with its infrastructure of autonomous centers and sanctuary squats, entail resistance and counter strategies of avoidance, solidarity, resistance, and resourcefulness.

The “Hotspot” regime of deceptively “safe” spaces, justified and administered by European authorities, “reflect the geopoliticization of humanitarianism and its geosocial discontents,” as geographers Katharyne Mitchell and Matthew Sparke put it in a study on the “geosocial efforts to construct safe space through practices of solidaristic accommodation.”[20] Mitchell and Sparke demonstrate “the ways in which Hotspots have made migrants unsafe, even as they have been simultaneously justified in humanitarian terms as making both Europe and refugees safer.”[21] But their article also illustrates “how counter-constructions of safe space can take divergent geosocial forms”—alternatives to migration management’s geopolitical abstractions, (under)commons that emerge out of “embodied space-making struggles for physical safety, personal dignity, organizational autonomy, radical democracy, spatial liberty, and social community.”[22]

Such counter-constructions of safe space should be pursued also in those places where the production and maintenance of “safety” has become a central concern of educational reality. In turn, the physical spaces, the material architecture of the learning environment, should not be abandoned as a consequence of their becoming hazardous (in zones of conflict, disaster and disease, in the endangered geographies of fugitivity). Replacing the presence in the classroom by a digital educational absence called “self sovereign identity,” the latest idea to uproot the vulnerable existences of people in transit even more (by delegating them to the biometric black boxes of blockchain technology), certainly is no solution, but rather the advent of a new problematic, as it supports the dissolution of any idea of the relationality or communality of learning.[23] The individual learner, one of the most cherished figures in Western educational theory, has always been a challenge for the designs, spatial and curricular, of mass education. The maxims of student-centred pedagogy simply contradicted the spatial conditions, pedagogical affordances and economic arithmetics of the capitalist school system. Moreover, the individual learner is also a defenseless figure and thus easily threatened. In the anxious isolation of neoliberal competition, particularly in the pandemic-enhanced Zoomscapes of distance learning, earlier utopias of a room of one’s own have somewhat paled. Alewya’s vision of the “safe space” as a place “to learn and to make friends,” read against the grain of the humanitarian-managerial approach for which she was enlisted, is a bold call to planners, pedagogues, and designers to seriously rethink not only the notion of safety but also that of space. It is also a reminder that ideas about education and the desire to learn are first and foremost located in the learner as a member of a community, be it that of the refugee camp or the sanctuary city.

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

World Health Organization (WHO), Partners in Life Skills Education—Conclusions from a United Nations Inter-Agency Meeting, Geneva 1999, https://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/30.pdf

2.

Quoted in Sarah Dryden-Peterson, Refugee Education. A Global Review, Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). November 2011, https://www.unhcr.org/4fe317589.pdf

3.

Marten Zwanenburg, “Keeping Camouflage Out of the Classroom: The Safe Schools Declaration and the Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use During Armed Conflict,” Journal of Conflict and Security Law, February 26, 2021, pre-publication, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcsl/krab002

4.

See, for example, Cyril Bennouna et al., “Monitoring and Reporting Attacks on Education in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Somalia,” Disasters 42, no. 2 (April 2018): 314–335.

5.

Leading towards such comparatist translocal readings, see, for example, Sveinung Sandberg, Atte Oksanen, Lars Erik Berntzen and Tomi Kiilakoski, “Stories in Action: the Cultural Influences of School Shootings on the Terrorist Attacks in Norway,” Critical Studies on Terrorism 7, no. 2 (2014): 277–296.

6.

See, for example, Keith Krause, “From Armed Conflict to Political Violence: Mapping & Explaining Conflict Trends”, Dædalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences 145, no. 4 (Fall 2016): 113–126.

7.

Lizbet Simmons, “The Docile Body in School Space,” in Torin Monahan and Rodolfo D. Torres, eds., Schools under Surveillance. Cultures of Control in Public Education (New Brunswick, N.J., and London: Rutgers University Press, 2010), 55–70, here 55.

8.

Robert Sommer, Personal Space. The Behavorial Basis of Design (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1969), 98.

9.

Ibid., 118–119.

10.

Madiha Afzal, From “Western Education Is Forbidden” to the World’s Deadliest Terrorist Group. Education and Boko Haram in Nigeria (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, April 2020), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/FP_20200507_nigeria_boko_haram_afzal.pdf

11.

Amnesty International, “Keep Away from Schools or We’ll Kill You.” Education under Attack in Nigeria (London: Amnesty International, 2013), 19.

12.

Janine Morna, Vulnerable Students, Unsafe Schools. Attacks and Military Use of Schools in the Central African Republic, New York: Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict, September 2015, https://watchlist.org/wp-content/uploads/2144-Watchlist-CAR_EN_LR.pdf

13.

For an early survey of the literature, quite tellingly published in a journal on real estate research, see Paul Michael Cozens, Greg Saville, and David Hillier, “Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED): a Review and Modern Bibliography,” Property Management 23, no. 5 (2005): 328–356.

14.

Daniel J. Lamoreaux and Michael L. Sulkowski, “Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design in Schools: Students‘ Perceptions of Safety and Psychological Comfort,” Psychology and Schools 58, no. 3 (March 2021): 475–493, here 83; the article refers to Sarah Lindstrom Johnson et al., “Assessing the Association between Observed School Disorganization and School Violence: Implications for School Climate Interventions,” Psychology of Violence 7, no. 2 (2017): 181–191, and Kevin J. Vagi et al., “Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) Characteristics Associated with Violence and Safety in Middle Schools”, Journal of School Health 88, no. 4 (April 2018): 296–305.

15.

Peter Marcuse, “Security or Safety in Cities? The Threat of Terrorism after 9/11,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 30, no. 4 (December 2006): 919–929, here 924.

16.

See, for example, Christina B. Hanhardt, Safe Space: Gay Neighborhood History and the Politics of Violence (Durham, N.C., and London: Duke University Press, 2013).

17.

The Roestone Collective, “Safe Space: Towards a Reconceptualization,” Antipode 46, no. 5 (2014): 1346–1365, here 1346.

18.

Ibid., 1354.

19.

Evie Papada et al., “Pop-Up Governance: Transforming the Management of Migrant Populations through Humanitarian and Security Practices in Lesbos, Greece, 2015–2017,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 38, no. 6 (2020), unpag., https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775819891167

20.

Katharyne Mitchell and Matthew Sparke, “Hotspot Geopolitics versus Geosocial Solidarity: Contending Constructions of Safe Space for Migrants in Europe,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 38, no. 6 (2020), unpag., https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818793647

21.

Ibid.

22.

Ibid.

23.

See, for example, Margie Cheesman, “Self-Sovereignty for Refugees? The Contested Horizons of Digital Identity,” Geopolitics, October 4, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2020.1823836

works as an independent scholar and curator. He authored and co-authored various books and organized exhibitions—most recently, Neolithic Childhood. Art in a False Present, c. 1930 (with Anselm Franke), and Education Shock. Learning, Politics and Architecture in

the 1960s and 1970s, both at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin. In 2015 he co-founded the Harun Farocki Institut in Berlin. Recent book publications include Knowledge Beside Itself. Contemporary Art’s Epistemic Politics Sternberg Press, 2020) and Politics of Learning, Politics of Space. Architecture and the Education Shock of the 1960s and 1970s (De Gruyter, 2021).