Learnings/Unlearnings: Emancipating and Emancipated Pedagogies – Decolonising and Co‐Creating Our Future Built Environment

Ashraf M. Salama, Jana Schade, Mustapha El Moussaoui, Kris Krois, Charalampos Spanos, Georgios Artopoulos, Constantinos Kritiotis, Afroditi Magou, Abeer Allahham

CATEGORY

Welcome to Learnings/Unlearnings Reader #3: Emancipating and Emancipated Pedagogies – Decolonising and Co‐Creating Our Future Built Environment, guest edited by Ashraf M. Salama and Meike Schalk. The Reader includes contributions from the section “Building and Playing: Enhancing Learning and Participation Through Environments and Public Spaces” from the conference Learnings/Unlearnings: Environmental Pedagogies, Play, Policies, and Spatial Design, which took place in Stockholm in September 2024.

Imagine there no built environments imposed from above, but emerged from the raw, grassroot, unfiltered creativity of every inhabitant.

Built environments have long been dictated by elite planners and architects and bureaucracies that serve privileged societies. Faced with deeply rooted social inequities, environmental degradation, and a rapidly evolving technology, educators, urban planners and designers, and architects are obliged to rethink how cities are built and maintained and how knowledge about their futures is generated, produced, and reproduced. This collection weaves together a diverse array of ideas—from alternative spatial paradigms, and Islamic thought to decolonised architectural pedagogy, AI-enabled public engagement, nature-based solutions, and the mobilization of participatory art-based methods for public spaces. Collectively, they offer threads for multiple learning opportunities and speak for an urgent pedagogical call to action: to unlearn established, habitually exclusionary, practices and to reimagine future built environments as inclusive and co-created realms of possibility.

Across their history and evolution, cities have been viewed as urban canvases for top‐down interventions. Contemporary debates in critical urbanism and sustainable development convey that our built environments are not passive milieus but dynamic, co‐created spaces. The contributions in this reader elucidate the urgency of unlearning outdated inherited practices and embracing new modes of engagement that give prominence to local wisdom, inclusivity, and innovation.

One critical thread offered by Ashraf Salama is the decolonisation of architectural pedagogy which builds on Connell’s Southern Theory (Connell 2007) and the dynamics of epistemics. For decades, architectural curricula have been dominated by Eurocentric narratives that marginalise non-Western and Indigenous epistemologies. This contribution contends passionately for a transformative educational framework that integrates diverse cultural perspectives, emphasises ecological responsibility, and repositions the architect as a facilitator rather than an authoritarian knowledgeable practitioner. The proposed model, synthesised from global case studies and aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), advocates for interdisciplinary learning, community engagement, and pluri-epistemologies. This approach seeks to dismantle entrenched hierarchies within the academy and presents a hope to prepare future architects to address complex social and environmental challenges through collaborative, context-sensitive practices.

A provocative thread exploring creative-artistic methodologies, that aims at empowering marginalised voices, specifically, girls, is offered by Jana Schade. Drawing inspiration from Virginia Woolf’s crucial call for creative freedom in A Room of One’s Own, this contribution maintains that urban spaces must be cultivated as canvases for self-expression for underrepresented groups. Engaging with feminist research and collaborative approaches, the work reveals how creative practices can enable girls to articulate their visions and challenge the spatial exclusion that has historically limited their agency. Through multi-case studies, expert interviews, and action research, this contribution exemplifies that art-based methods can be a powerful catalyst for social and cultural transformation.

Digital innovation forms another vigorous thread of the discourse in this reader. In a time where artificial intelligence (AI) progressively shapes creative and cultural industries, Mustapha El Moussaoui and Kris Krois explore how AI can be harnessed as a tool for speculative urban design interventions. Using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and related digital tools, a case study from Don Bosco in Bolzano, Italy, illustrates that AI-generated imagery can act as a catalyst for participatory design. These images serve as provocations—starting points that spark collective imagination and critical dialogue among community members. Nevertheless, while digital tools offer stimulating possibilities, this contribution also raises important questions about the risks of reinforcing pre-existing biases if technology is not integrated ethically. Therefore, the challenge is to ensure that AI functions not as a prescriptive force but as an enabler of inclusive, bottom-up decision-making.

Complementing the digital perspective, Charalampos Spanos, Georgios Artopoulos, Constantinos Kritiotis, and Afroditi Magou present a roadmap for inclusive Nature-Based Solutions (NBS). In the face of escalating environmental degradation, the integration of nature-inspired approaches into urbanism is increasingly critical. This contribution outlines a participatory, co-diagnostic process employed along the Pedieos River in Cyprus. This approach utilises Citizen Science and engages a diverse spectrum of stakeholders—municipal authorities, NGOs, and local communities—through methods such as serious geo-games, and phygital interactions with nature. The process represents how unlearning exclusionary practices can open new avenues for sustainable and resilient urban interventions. It stresses the possibility for NBS to enhance ecological outcomes while empowering communities by validating local, lived knowledge and facilitating collaborative decision-making.

Finally, a captivating thread interrogates the traditional wisdom of creating the urban realm. In modern capitalist cities, public spaces are often depicted as neutral zones of democratic interaction and engagement. However, drawing on the critical insights of geographers, philosophers, and social scientists, Abeer Allahham exposes these spaces as territories of power and hegemony, where the state exercises its dual role as sovereign and landowner to regulate access and maintain social order. Contrasting this with the fluid, communal spatial practices found in traditional Islamic cities—emanated from cultural and religious traditions—this contribution offers an alternative vision. In these traditional contexts, the absence of a rigid public–private dichotomy in the urban realm enabled communities to manage and share space more equitably. Such insights resonate with wider contemporary calls to decentralise urban control and foster participatory forms of use, appropriation, and spatial management.

This reader challenges entrenched canons through criticising elitist models of both education and practice, deconstructing Eurocentric educational frameworks, and questioning conventional urban practices. It calls for concerted efforts that empower communities, whether through re-envisioned public spaces inspired by traditional practices, decolonised curricula, AI-enhanced participatory design, inclusive nature-based solutions, or creative artistic interventions. The underlying imperative is clear: we must unlearn obsolete inherited practices and embrace collaborative, context-sensitive approaches that value the lived experiences and diverse knowledge types.

Drawing on the emancipatory philosophies of eminent pedagogues and selected radical urban theories, these contributions argue that design pedagogy is not a neutral process but a deeply political act of liberation. They echo the narrative that every street, park, and building is a site of possibility—a setting for collective creativity and critical dialogue.

Across the five contributions, a clear commonality emerges: a call for a radical rethinking of built environment futures through participatory, inclusive, and decolonised pedagogies. Each work challenges conventional, top‐down approaches—whether in public space management, or architectural pedagogy—contending that built environments should be co‐created by communities rather than imposed by technocratic creams. There is a shared emphasis on unlearning outdated practices and integrating diverse forms of knowledge, from Indigenous and non-Western traditions to cutting-edge digital innovations. Likewise, the contributions collectively stress that built environments must be reimagined as dynamic realms for collective empowerment, social justice, and ecological resilience. This convergence of ideas accentuates a transformative vision where architectural and urban pedagogy are centred on learning processes that genuinely reflect the lived experiences and aspirations of inhabitants.

Reference

Conell, R. 2007. Southern Theory: Social Science and the Global Dynamics of Knowledge. Polity Press.

Contents

A Decolonised Architectural Pedagogical Framework: An Imperative for Reform

Ashraf M. Salama

What if architectural curricula no longer treated non-Western traditions as supplementary but instead positioned them as fundamental to shaping a truly inclusive and equitable built environment?

Imagine if decolonised pedagogy redefined the role of the architect, not as an authority, but as a facilitator who co-creates with communities to address historical and spatial injustices?

This essay examines the transformation of architectural education through the lens of decolonisation which challenges the dominance of Eurocentric frameworks and advocates a more inclusive, community-driven, and sustainability-focused approach. The essay critically engages with the systemic marginalisation of non-Western perspectives and underscores the necessity of integrating Indigenous and vernacular knowledge systems into architectural curricula. Drawing from five global case studies, a synthesis of key pedagogical characteristics is undertaken while mapping them to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to generate a new decolonised framework, ADAPT2SDG. The discussion unveils five fundamental pillars—ecological responsibility, social equity, historical awareness, community engagement, and interdisciplinary learning—that provide a foundation for embedding decolonised content in architectural and urban pedagogy. Repositioning marginalised voices at the core of pedagogical practice, the essay proposes a transformative and adaptable educational model that fosters greater inclusivity, responsiveness to local contexts, while reimagining the architect’s role in shaping equitable and sustainable built environments.

Architectural education has historically been rooted in Eurocentric frameworks, often marginalising non-Western perspectives and excluding Indigenous knowledge systems. While conventional pedagogies have evolved, they continue to lack an explicit articulation of decolonised characteristics that fully integrate cultural inclusivity, social equity, and environmental responsibility (Salama & Burton, 2023). The urgency to decolonise architectural education stems from its deeply entrenched Eurocentric legacies. Traditions such as the École des Beaux-Arts and Bauhaus have long shaped architectural pedagogy, reinforcing narratives that prioritise Western knowledge while systematically erasing Indigenous, vernacular, and community-based design traditions. Scholars argue that genuine decolonisation necessitates dismantling these hegemonic structures rather than merely diversifying curricula with tokenistic inclusions (Fanon, 1965; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2016; Tuck & Yang, 2012). Centring marginalised voices within pedagogical practice, the essay proposes a transformative and adaptable educational model that fosters inclusivity, responsiveness to local contexts, and a reimagined role for architects in shaping equitable and sustainable built environments.

To explore the complexities of decolonisation, a three-phase approach is employed. It first examines five global architectural education initiatives to identify key characteristics of decolonised pedagogy. Second, it aligns these pedagogical characteristics with the SDGs, demonstrating their contribution to sustainability and equity. Third, it consolidates the findings into a structured yet adaptable pedagogical model.

Five global case studies offer insights into how decolonised pedagogy manifests in architectural education. Race, Space, and Architecture (RSA) critically interrogates the intersection of race and spatial practices. Developed through interdisciplinary collaboration, it challenges dominant architectural narratives by integrating literature, film, and historical analysis to unpack spatial injustices (Tayob, 2022). As an open-access curriculum, RSA broadens accessibility and empowers students to engage with racialised histories of architecture. The Meeting of Knowledges (MOK) integrates Indigenous and Afro-Brazilian architectural knowledge into university curricula, fostering epistemic plurality. Through partnerships between traditional master builders and academic faculty, MOK creates an inclusive learning environment that challenges Western academic hegemony (De Carvalho, 2022).

Another significant case, Pedagogies of Connection and Change (PCC), employs community-driven, experiential learning methodologies. Students engage in live projects using “Fast Attack Urbanism,” ensuring immediate impact while addressing socio-spatial inequalities (Haiek & Cadalso, 2022). This approach redefines the architects’ role, positioning them as facilitators of grassroots transformative change. The Global Housing Program (GHP) foregrounds participatory design and visual ethnography, integrating local knowledge into sustainable housing solutions. By engaging students in immersive research, GHP equips them with the skills to address real-world housing challenges (Mota & van Gameren, 2022). Impact Labs—Education for Sustainability (IL-EfS) fosters interdisciplinary and inquiry-based learning, guiding students to develop innovative solutions aligned with the SDGs. By embedding sustainability into pedagogical practices, IL-EfS ensures students graduate with the skills needed to address pressing environmental and social challenges (Meth et al., 2022).

These preceding case studies collectively demonstrate the varied approaches to decolonised pedagogy, from interdisciplinary curriculum design (Race, Space, and Architecture) to community-driven learning models (Pedagogies of Connection and Change). While some focus on Indigenous knowledge integration (Meeting of Knowledges), others prioritise experiential methodologies (Impact Labs). The diversity of these approaches accentuates the need for adaptable approaches predicated on ADAPT2SDG, which synthesises these strategies into a cohesive framework for educational reform.

While mapping the characteristics of the five cases to SDGs, it should be noted, that the SDGs themselves originate in frameworks with inherent power dynamics. Therefore, architectural educators must incorporate, and engage with them critically, recognising both their value and their potential to reinforce undesired hierarchies if left unexamined. Rather than utilising SDGs as universal prescriptions, they should be reinterpreted and contextualised through diverse cultural perspectives, ensuring they function as inclusive, transformative tools within architectural curricula.

The findings from these case studies coalesce into ADAPT2SDG, a structured yet flexible framework for embedding decolonised pedagogy within architectural education. Through a synthesis of the five cases, viewed as global best practices, ADAPT2SDG encapsulates the defining characteristics of decolonised learning and provides a clear roadmap for implementing these methodologies in academia (Figure 1). Collaborative and transdisciplinary practices within ADAPT2SDG enrich architectural education by integrating diverse disciplines, ensuring students engage with a broad spectrum of knowledge beyond traditional vocational training. Community-centric learning lies at the core of this framework, fostering a pedagogical model that is deeply rooted in local contexts and real-world challenges.

Figure 1. ADAPT2SDG—A Decolonised Architectural Pedagogical Framework (Source: Ashraf M. Salama, Lindy Osborn Burton, Madhavi Patil, 2025 forthcoming).

The model further reinforces the importance of critical engagement with societal issues, encouraging students to address urban inequalities, climate resilience, and systemic injustices through architecture. ADAPT2SDG also emphasises accessibility and openness, ensuring that educational resources are freely available and inclusive. Prioritising empowerment through education, the framework fosters leadership and critical thinking, equipping students with the tools to challenge dominant Euro-centric paradigms. Cultural relevance is another essential component, embedding Indigenous and vernacular knowledge into architectural education rather than treating them as peripheral topics. Experiential and inquiry-based learning ensures that students gain hands-on experience with design methodologies that respond to pressing social and environmental needs.

ADAPT2SDG champions inclusive and diverse content, ensuring that the voices and contributions of historically marginalised communities are fully integrated into architectural curricula. Its emphasis on interdisciplinary integration brings together knowledge from sociology, environmental science, and Indigenous studies, fostering a holistic understanding of architecture’s role in society and in the construction and re-construction of social reality. A pluralistic academic environment supports multiple epistemologies, dismantling the rigid hierarchies that have long dictated architectural discourse. The framework prioritises sustainability by entrenching ecological responsibility and regenerative practices into all aspects of education. In essence, ADAPT2SDG promotes the democratisation of technology, ensuring that digital tools are widely accessible and can be leveraged to advance decolonised learning objectives.

Implementing ADAPT2SDG requires a series of strategic reforms within architectural education. Institutions must take proactive steps to revise their curricula, incorporating non-Western perspectives into history and design courses. Strengthening community partnerships is essential for ensuring that participatory design approaches are integrated into pedagogical practices. Challenging deeply rooted and dominant power structures within academia is crucial, as it enables a shift away from exclusionary traditions towards more equitable forms of knowledge production and reproduction. This is not all; a firm commitment to sustainability ensures that architectural education actively contributes to global environmental and social justice efforts.

As architectural education continues to evolve, institutions, educators, and education policymakers must collectively commit to dismantling exclusionary reductionist pedagogies and fostering a curriculum that embraces diversity, inclusivity, and sustainability. Universities should prioritise revising their curricula, ensuring Indigenous and marginalised knowledge systems actively shape architectural education. Academic institutions must establish partnerships with communities and practitioners to create opportunities for students to engage in real-world authentic and decolonised design processes. Architects and educators must critically reflect on their own roles in perpetuating or disrupting systemic inequities. They must advocate policies and support educational structures that are truly inclusive. Only through sustained endeavours and collaboration can ADAPT2SDG drive meaningful change which ensures that architectural pedagogy departs from exclusionary paradigms while actively contributes to a more just and inclusive built environment worldwide.

References

Carvalho, José Jorge de. 2022. “The Meeting of Knowledges in the Universities: A Movement to Decolonise the Eurocentric Academic Curriculum in Latin America.” In The Routledge Companion to Architectural Pedagogies of the Global South, edited by Harriet Harriss, Ashraf M. A. Salama, and Ane Gonzalez Lara, 67–76. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003018841.

Fanon, Frantz. 1965. A Dying Colonialism. Translated by Haakon Chevalier. New York, NY: Grove Press.

Haiek, Alejandro, and Xenia Adjoubei. 2022. “Pedagogies That Guarantee Change: Live Project Classrooms in Venezuela and Latin America.” In The Routledge Companion to Architectural Pedagogies of the Global South, edited by Harriet Harriss, Ashraf M. Salama, and Ane Gonzalez Lara, 433–450. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003018841.

Meth, Deanna, Claire Brophy, and Sheona Thomson. 2023. “A Slippery Cousin to ‘Development’? The Concept of ‘Impact’ in Teaching Sustainability in Design Education.” Teaching in Higher Education 28 (5): 1039–1056. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2023.2198638.

Mota, Nelson, and Dick van Gameren. 2022. “Dwelling Beyond Cultural Differences: Architectural Education for Peripheral Urbanization in Bangladesh, Ethiopia and India.” In The Routledge Companion to Architectural Pedagogies of the Global South, edited by Harriet Harriss, Ashraf M. Salama, and Ane Gonzalez Lara, 419–432. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003018841.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J. 2016. “The Imperative of Decolonizing Modern Westernized University.” In Decolonizing the University, Knowledge Systems and Disciplines in Africa, edited by Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni and Siphamandla Zondi. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

Salama, Ashraf M., and Lindy Osborne Burton. 2023. “Pedagogical Traditions in Architecture: The Canonical, the Resistant, and the Decolonized.” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 35 (1): 47–71.

Tayob, Huda. 2022. “Race, Space and Architecture.” In The Routledge Companion to Architectural Pedagogies of the Global South, edited by Harriet Harriss, Ashraf M. Salama, and Ane Gonzalez Lara, 200–212. London, UK: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003018841.

Tuck, Eve, and Wayne Yang. 2012. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 (1): 1–40. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:143164941.

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2024. “What Are the Sustainable Development Goals?” United Nations Development Programme. Accessed August 9, 2024. https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals.

A Space of Our Own: Creative-artistic methods to include girls’ perspectives in urban public space design

Jana Schade

“Women have sat indoors all these millions of years, so that by this time the very walls are permeated by their creative force, which has, indeed, so overcharged the capacity of bricks and mortar that it must needs harness itself to pens and brushes and business and politics.”

—Woolf 1929, 73.

Inspired by Virginia Woolf’s call for women to have a room of their own to cultivate creative freedom, this essay demonstrates how girls can reclaim urban public spaces through creative-artistic methods. Woolf’s vision of women’s creative energy overflowing from the confines of domestic spaces into the expanse of society captures the ongoing struggle for female visibility and agency. While there have been important efforts to increase the empowerment of girls and women in the nearly one hundred years since the publication of her essay “A Room of One’s Own,” the contemporary urban sphere continues to be deeply interwoven with injustices and inequalities (Kern 2020, 105), perpetually limiting girls opportunities to engage with and shape their surroundings. The history of spatial marginalisation highlights the need to reclaim and reshape urban public spaces to reflect girls’ needs and visions. Recognizing the political nature of the urban sphere, as emphasised by Henri Lefebvre and Michel Foucault, this work argues that it is imbued with power dynamics that not only perpetuate social inequalities, but also hold the possibility of transforming them (Lefebvre 1991, 47; Foucault 1984, 255).

“To change life, however, we must first change space.”

— Lefebvre 1991, 190

Virginia Woolf’s way of linking female creativity and spatiality served as a source of inspiration for my degree project “A Space of Our Own” (2024), that set out to explore the following questions:

- What role can creative-artistic methods have in relation to contributing to a broader understanding of urban public spaces for girls?

- What conditions should be met to facilitate meaningful planning processes with girls?

- What abilities should planners and facilitators working with creative-artistic methods have?

This work adopts a feminist research approach and uses methodologies including a multi-case study, expert interviews, and action research with girls from a 6th grade at a school in Nacka to draw on real-life examples and insights. The findings are not to be understood as absolute conclusions, but rather as a guiding approach and orientation to support successful creative-artistic participatory projects with girls.

Urban planning processes predominantly employ language. Embracing the rich perspectives and multifaceted nature of urban space, describing spatiality solely through language restricts the depth and complexity of its perceptual experiences. When broadening and discovering new perspectives of spatial experience and knowledge, it’s beneficial to explore various modes of expression, and artistic expression can enhance the sensory richness of urban environments in ways that language cannot capture (Cisneros et al 2021, 63). Given the observations and learnings that can be drawn from the expert interviews, the multi-case study and the action research, creative-artistic methods have shown the potential to activate and aid girls in exploring urban public space and formulate their own thoughts and ideas, contributing important situated knowledge that broadens urban perception. The employment of creative-artistic methods facilitates the extension of conventional modes of written or verbal communication in urban planning processes. As John Dewey describes, art enhances sensory and emotional understanding (Dewey 1980, 13), thereby enabling a more nuanced representation of the girls’ experiences and thoughts. In all cases investigated, the use of creative-artistic methods made visible new insights, perspectives, and ideas that prevailing planning structures tend to overlook. The research was not able to categorise the employed creative-artistic methods in terms of their efficiency or suitability, as their use is highly dependent on the respective context. This can further be explained by the fact that art and creativity cannot be measured with instrumental logic (Wiberg 2022, 403). Despite their merits, it must be acknowledged that these methods are not without their limitations, and as a standalone solution, cannot solve underlying social or sustainability issues (Holub 2008, 108), however artistic approaches can lead to creating meaningful collaborative processes that foreground the voices of girls in planning and design.

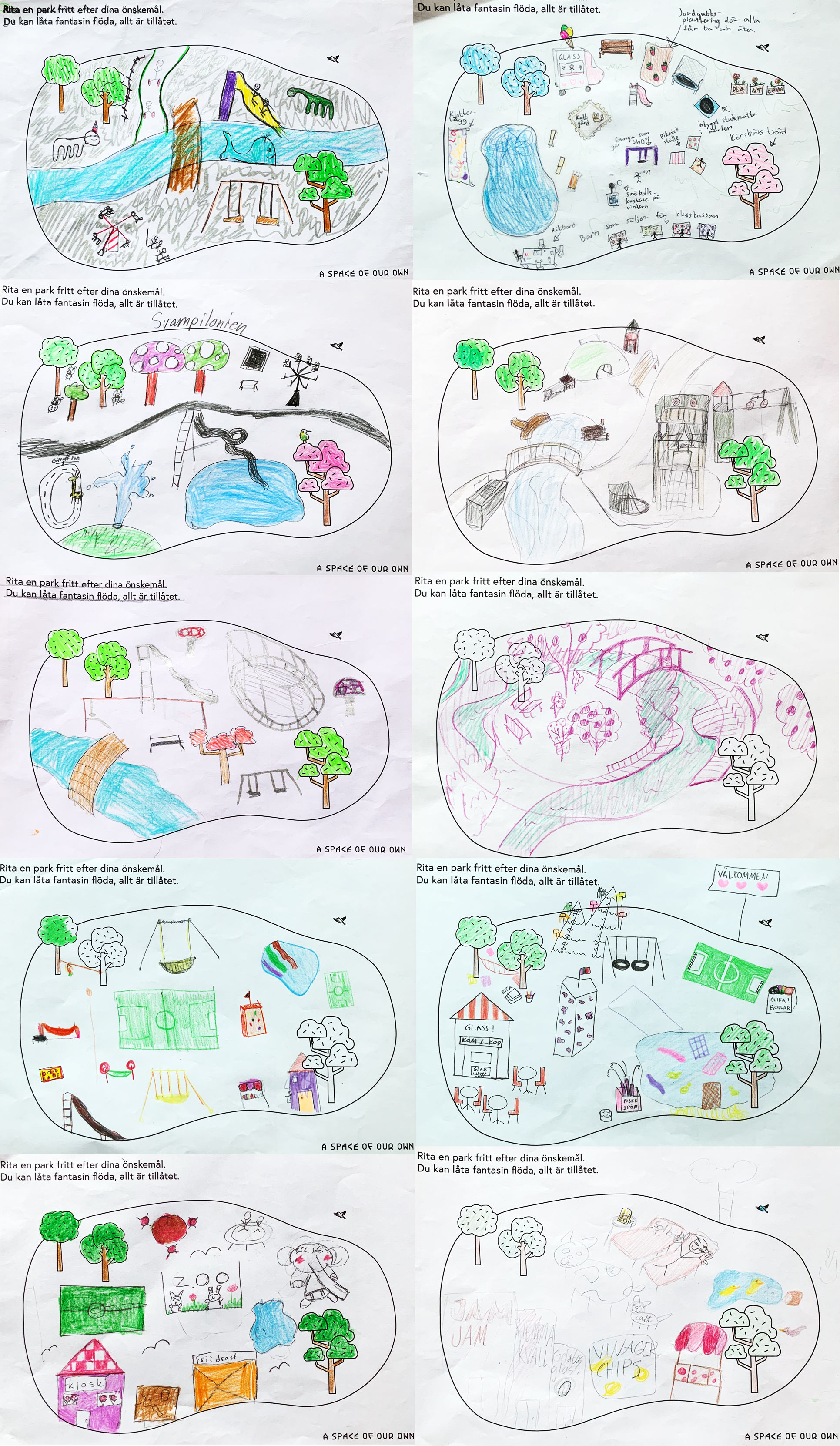

Imaginary parks drawn by girls during an action research project with a 6th-grade class in Nacka, Stockholm, Sweden. 2024. Photo: Jana Schade

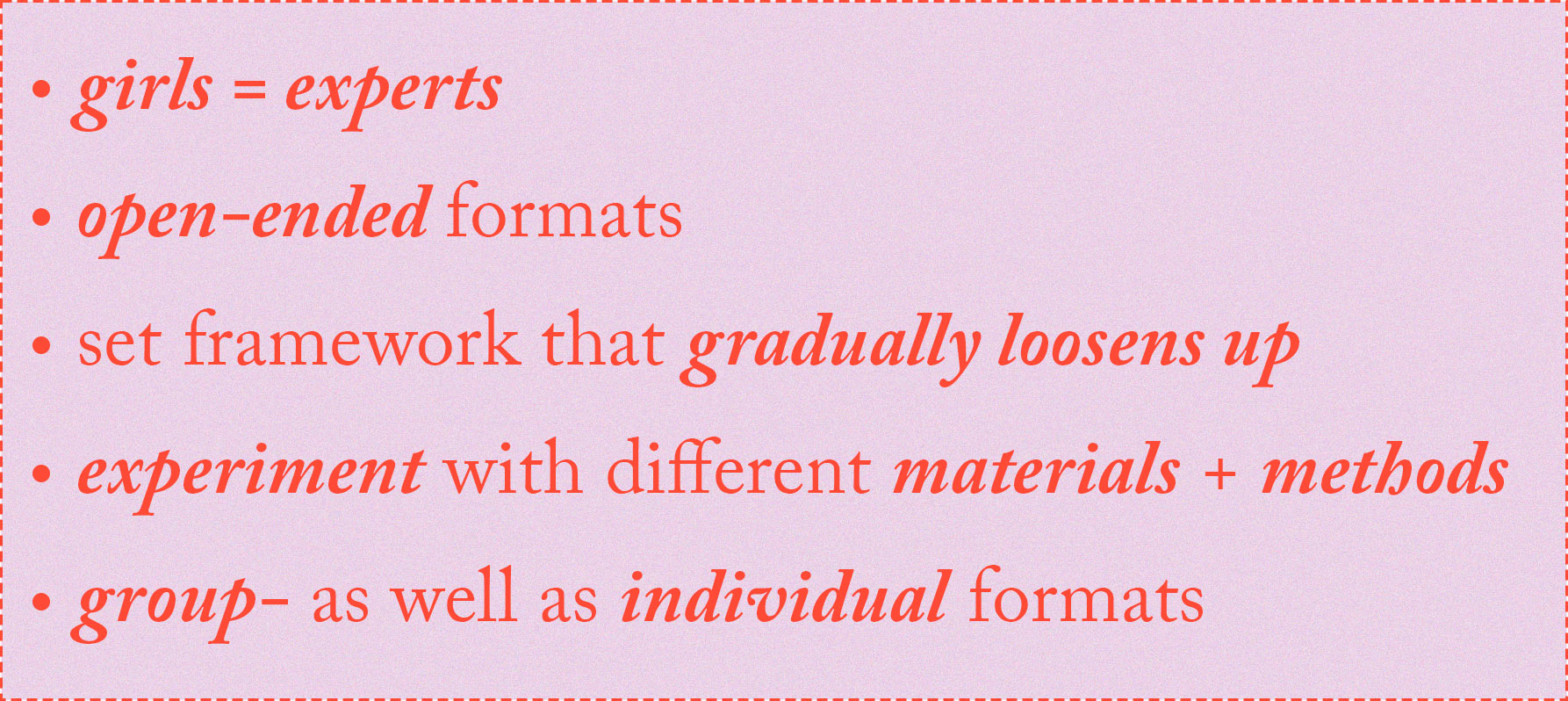

Key takeaways for frameworks for meaningful creative-artistic participatory processes. 2024. Graphic by Jana Schade

To ensure active participation on equal terms, the basic principle that was repeatedly mentioned—both in the examples of the multi-case study as well as during the expert interviews—is that girls are the experts and should be met on even ground, without further mediation (Rubin 2024). This may sound simple, but when working on projects involving various adult stakeholders, it’s important to continuously refocus on this priority. The use of creative-artistic approaches involves navigating unpredictable space with uncertain outcomes (Metzger 2011, 31). The aim is to insure a constantly evolving, adaptable dynamic that allows flexible reactions to unforeseen changes (Holub 2008, 372). It’s thus evident that creative-artistic methodologies cannot fulfil direct expectations, nor can their contextual learnings be directly transferred to another setting, but the focus lies on the process itself, not on the achievement of pre-set objectives. An open-ended framework provides the necessary adaptability and flexibility in which the process can reply to unexpected turns, and is constantly evolving and shaping itself (Holub 2008, 372). Interviewing an atelierista (2024) revealed that it is essential to establish a certain framework to make sure that the girls are not overwhelmed. This framework, however, should gradually loosen up and allow for free experimentation within certain boundaries. The initial framework and orientation can, for example, be assured through the definition of parameters such as a specific material or format. Nonetheless, a diverse range of options for creative expression ensures that all participants are able to find a form of expression that aligns with their individual needs and preferences (Görgen 2024). In my own action research—a project with girls from a 6th grade at a school in Nacka, as well as during the interview with a primary school teacher—it became evident that aspects such as the group dynamic can be decisive for the results of participatory formats. This can be addressed by offering both group, as well as individual formats, to give different personalities suitable and safe spaces to communicate their thoughts. In addition to these framework conditions, it is particularly important to consider the role of the planners and facilitators in guiding these processes.

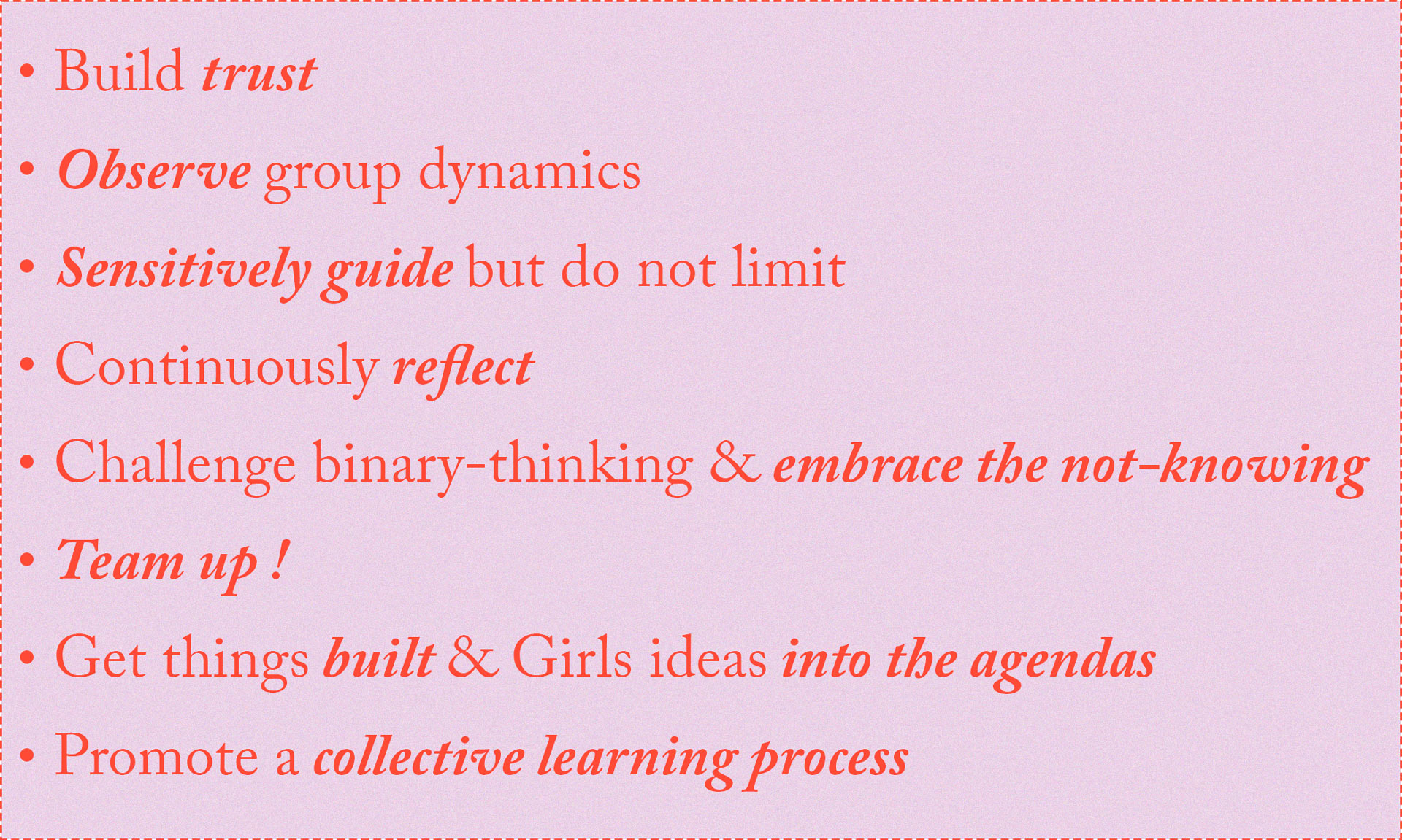

Key takeaways for the role of planners and facilitators. 2024. Graphic by Jana Schade

Moving within experimental spaces and using creative-artistic methodologies requires reflection on the role of planners and facilitators. Especially when working with girls, planners and facilitators need to be aware of their own behaviours and approaches. The establishment of a foundation of trust between planners and participants is crucial. This necessitates sensitivity, empathy, and trust-building behaviour, and the maintenance of strong ethical principles—open, honest communication, active listening, and observing the participants well-being. It’s important to make sure that the participants are not exposed to negative feelings such as pressure or stress and that their participation is fully voluntary.

This also includes observing group dynamics. As mentioned above, planners and facilitators must possess necessary skills to create a safe and inclusive environment, ensuring that more outgoing personalities do not dominate the process and that quieter individuals feel encouraged to express their thoughts. It’s important to accompany these participatory projects with sensitive guidance while ensuring that the girls are not being limited. Generally, the role of the planner is passive, aiming to set the framework conditions while not intervening in the process itself. This sensitive approach to leading and facilitating participatory processes also demands an internal process of self-reflection, assessing and adapting to the respective context and situation. Working with creative-artistic methods encourages one to actively challenge binary thinking and embrace a state of uncertainty, or not-knowing. Facing the unknown, it is beneficial to adopt a team-based approach, leveraging the potential of collaborative efforts. Projects reviewed during the multi-case study demonstrated the significance of teaming up with schools or institutions to activate girls as participants. Collaborating with artists can help with devising and implementing creative methods and the commitment and support of municipalities is crucial to ensure the practical implementation of girls’ ideas and visions. Building on this, planners and facilitators should strive to get the girls’ visions built and their ideas onto the agendas in order to enable the participants experience of self-efficacy. Ultimately, documenting and sharing knowledge and experiences fosters a collective learning process that contributes to the creation of more inclusive, fair, and socially sustainable living spaces for all.

“For masterpieces are not single and solitary births; they are the outcome of many years of thinking in common, of thinking by the body of the people, so that the experience of the mass is behind the single voice.”

—Virginia Woolf 1929, 55

A Space of Our Own’ demonstrates the potential of creative-artistic participatory approaches to empower young women to reclaim urban public spaces. Incorporating these methods into planning processes and establishing the necessary frameworks can facilitate the development of inclusive public spaces that respond to the diverse needs and experiences of young women. It’s crucial for planners and policymakers, as well as architects and urban designers, to embrace these insights to shape public spaces into truly democratic platforms that enable equal representation and social transformation.

References

Cisneros, Rosemary E., Marie Crawley, and Sara Whatley. 2021. “Mapping a City’s Energy: Using Digital Storytelling to Facilitate Embodied Experiences of Urban.” Streetnotes 27. https://dx.doi.org/10.5070/S527047055.

Dewey, John. 1980. Art as Experience. Perigee Books.

Holub, Barbara. 2018. Direkter Urbanismus: Die Rolle von Kunst und Künstlerischen Strategien für Gesellschaftlich Engagierte Stadtplanung. Technische Universität Wien. https://doi.org/10.34726/hss.2018.15259578.

Görgen, Verena. In discussion with the author. March 7, 2024.

Johnston, Chris, and Hayden Lorimer. 2014. “Sensing the City.” Cultural Geographies 21 (4): 673–680. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26168607.

Kern, Leslie. 2020. Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-Made World. London: Verso.

Lefebvre, Henri. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

Metzger, Jonathan. 2011. “Strange Spaces: A Rationale for Bringing Art and Artists into the Planning Process.” Planning Theory 10 (3): 213–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095210389653.

Rubin, Rebecca. In discussion with the author. April 12, 2024.

Schade, Jana. 2024. A Space of Our Own: The Potential of Creative-Artistic Methods to Include Girls’ Perspectives in Urban Public Space Design. Master thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kth:diva-352318.

Wiberg, Sofia. 2022. “Planning with Art: Artistic Involvement Initiated by Public Authorities in Sweden.” Urban Planning 7 (3): 394–404. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v7i3.5367.

Woolf, Virginia. 1929. A Room of One’s Own. London: Hogarth Press.

Engaging the Dwellers to Reimagine Their Public Space Supported by AI

Mustapha El Moussaoui and Kris Krois

Participants making scenario choices. Photo by Mustapha El Moussaoui

The future of urbanism is undergoing a profound transformation, among others through rapid technological advancements and a critical rethinking of how cities function in the digital age. Artificial intelligence (AI) and other emerging technologies are reshaping urban planning. Beyond their technical applications, they hold the potential to transform pedagogical frameworks in higher education, challenging conventional approaches to city-making. This transformation is not uniform nor purely technological – it is deeply embedded in socioeconomic and political structures, governance models and institutions, and, crucially, in how the discourse about urban futures is produced and disseminated. AI, when integrated thoughtfully, has the potential to foster participatory urbanism, ensuring that technological progress aligns with collective needs rather than imposing the design of social infrastructures and public spaces. More importantly, it presents an opportunity to enrich urban pedagogy, positioning learning as an iterative, community-driven process where AI serves as both a tool and a medium for collectively imagining and discussing, inclusive urban futures.

This paper explores these themes through a case study in Don Bosco, Bolzano, Italy, where AI was leveraged to reimagine public spaces through a community-driven process. In October 2023, six urban scenarios were visualised by the authors, incorporating prior research and addressing contemporary urban challenges. Text-to-image/image-to-image tools played a central role in making potential futures tangible, and thus discussable by diverse publics, facilitating iterative feedback loops. The participatory process underscored the usefulness of embedding AI into urban planning not as a prescriptive force but as an enabler of collective imagination and critical discourse. By involving residents in shaping their environment, this paper examines how AI, when embedded in participatory urban planning, can act as a tool for collective imagination. Through the case study in Don Bosco, Bolzano, we demonstrate how AI-generated speculative scenarios facilitate public engagement, challenge urban hierarchies, and inspire alternative futures.

Co-design is a widely recognized approach in creative practice, particularly within the public sector. It encompasses participatory, co-creation, and open design processes. Sanders (2008) situates co-design within the broader notion of co-creation, tracing its roots back to participatory design methodologies developed in Scandinavian countries during the 1970s, as well as the ‘Design Participation’ conference held in the UK in 1971. Contemporary design research and methodologies increasingly emphasize co-design as an essential tool for democratic urban development. This shift is driven by an erosion of the traditional single-designer model and a move toward strategic, collective, and non-tokenistic engagement (Martin, 2009; Lee, 2008).

By integrating co-design principles into urban development initiatives, cities ensure that urban technologies and social infrastructures align with the values and requirements of the communities they serve. This participatory approach leverages collective intelligence and creativity from diverse stakeholders, including residents, policymakers, urban designers, and technologists, fostering more inclusive and sustainable urban growth. By involving citizens in the design process, urban solutions are more likely to be embraced and cared for. For instance, co-design can be instrumental in developing smart transportation systems, ensuring they are user-friendly and efficient based on commuter insights.

Co-design democratises urban innovation by dismantling traditional hierarchies, allowing citizens to actively shape their environments. In the context of smart cities, where technological advancements often create a disconnect between decision-makers and the public, embedding co-design principles ensures that innovations serve the broader public interest. By prioritizing bottom-up approaches, cities can foster a sense of ownership and engagement among residents, leading to more sustainable urban solutions (Manzini, 2015).

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) — an AI framework — offer significant potential in urban design by enabling speculative future scenarios that transcend conventional design limitations. By generating visualizations of future scenarios, GANs can engage the public more effectively in imagining and shaping their future urban spaces. Introduced in 2014 by Ian Goodfellow and colleagues, GANs consist of two neural networks—the generator and the discriminator—which engage in a continuous adversarial process. The generator creates data samples (e.g., images), attempting to pass them off as real, while the discriminator evaluates and distinguishes between authentic and generated inputs. Over time, this dynamic process allows GANs to produce highly realistic visual content applicable to urban planning (Goodfellow et al., 2014).

In October 2023, during a project to redesign the public space of Don Bosco, Bolzano, six visual scenarios were created—five of them using GANs through the image generators Midjourney V6 and ComfyUI, while one scenario was manually designed based on the author’s interpretation of local urban challenges and needs. The first four scenarios were hypothetical scenarios derived from prior research (Habicher et al., 2022) exploring different futures in South Tyrol. They aimed to align with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the European Green Deal, which emphasize sustainable development paths:

- Regional Consciousness – “Our strength lies in tradition.”

- Neo-Cosmopolitanism – “Think global, act local.”

- Individual Freedom – “I am the architect of my own happiness.”

- Green Innovation – “There is a (technological) solution to everything.”.

Two additional scenarios were introduced to address Don Bosco’s unique context. One envisioned a human-centered future driven by residents’ comments. The other served as a dystopian cautionary tale, depicting increased inequalities and environmental degradation due to a lack of care for the public good (Tronto, 2019).

To enhance the participatory aspect of these scenarios, a public event was held in Bolzano where residents engaged with those visualized scenarios. This event allowed the local population to provide feedback on five key public spaces.

World of Green Innovations scenario of Piazza Don Bosco, created by a GAN tool. Photo by Mustapha El Moussaoui

Participants making scenario choices. Photo by Mustapha El Moussaoui

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into participatory urban planning, as demonstrated in Don Bosco, Bolzano, offers a perspective on the intersection between new emerging technologies and the public. With approximately 180 participants engaging in the discussion process, this experiment underscored the potential and limitations of AI as a medium for rethinking public space. While AI-generated speculative scenarios opened new discursive spaces, their implementation raised fundamental questions about the role of technology in urban decision-making: does AI democratize participation, or does it risk reinforcing existing imaginaries under the guise of inclusion? Is it really bringing to the table something new, or is it just reinforcing stereotypes?

One of the most significant observations from the event was the way in which participants engaged with the AI-generated scenarios. The speculative urban futures presented by GANs did not serve as predefined solutions but as provocations—starting points for debate, critique, and reconfiguration. Unlike conventional top-down urban planning methods, where expert-driven proposals dictate transformation, this process allowed participants to contest, adapt, and reinterpret the proposed scenarios according to their lived experiences. However, this engagement also exposed a fundamental paradox: while AI made potential futures more tangible, many participants tended towards the more spectacular images rather than to the more humble scenarios incorporating actual problems and needs. To which degree are both, the AI images and the preferences of people influenced by images of spectacular worlds, as known from movies, series, marketing communication and social media?

However, the participatory nature of this process showed, how AI generated images can be helpful to make scenarios discussable, but more attention needs to be given to biases of both AI and humans. By inviting a diverse group of residents — including children, young adults, and the elderly — into the decision-making process, the project highlighted an exchange between different perspectives, revealing generational and socio-cultural variations in how public space is perceived and valued. While younger participants approached the AI-generated scenarios with curiosity and speculative thinking, older participants were often more cautious, evaluating the proposals through the lens of historical continuity, social cohesion, and infrastructural feasibility.

Beyond the immediate feedback collected during the event, this experiment raised broader questions about the mechanisms of agency within AI-mediated urbanism. While the public was actively engaged in discussing scenarios, expressing preferences and providing qualitative insights, the extent to which this input can be translated into actual urban change remains to be explored. Participation, even when structured to be inclusive, does not automatically equate to agency. AI, as a generative tool, can visualize possibilities, but its role in shaping tangible urban futures depends on the institutional and political willingness to integrate public feedback into concrete policies and spatial interventions. Additionally, AI, when framed within a participatory and discursive process, has the capacity to act as more than just a planning tool—it becomes a mechanism for civic participation, encouraging residents to critically engage with the forces that shape their urban environments.

This study highlights the transformative potential of AI in participatory urbanism, yet it also raises fundamental questions: To what extent do AI-generated speculative scenarios truly democratize urban decision-making? How can we ensure that AI serves as a tool for empowerment rather than an amplifier of pre-existing biases? Future research should explore approaches for integrating AI-generated community insights into tangible frameworks, ensuring that participatory design extends beyond visualisation to meaningful change.

References

El Moussaoui, Mustapha. 2024. “Spatial Transformation—The Importance of a Bottom-Up Approach in Creating Authentic Public Spaces.” Architecture 4 (1): 14–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture4010002.

Goodfellow, Ian, Jean Pouget-Abadie, Mehdi Mirza, Bing Xu, David Warde-Farley, Sherjil Ozair, and Yoshua Bengio. 2014. “Generative Adversarial Nets.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 27.

Habicher, Daniel, Fabian Windegger, Heiko A. von der Gracht, and Harald Pechlaner. 2022. “Beyond the COVID-19 Crisis: A Research Note on Post-Pandemic Scenarios for South Tyrol 2030+.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 180: 121749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121749.

Lee, Youn-Kyung. 2008. “Design Participation Tactics: The Challenges and New Roles for Designers in the Co-Design Process.” CoDesign 4 (1): 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875613.

Manzini, Ezio. 2015. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Martin, Roger. 2009. The Design of Business: Why Design Thinking Is the Next Competitive Advantage. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

Tronto, Joan (2019). Caring Architecture. In Angelika Fitz and Elke Krasny, eds. Critical care: architecture and urbanism for a broken planet. Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press

Sanders, Elizabeth B.-N., and Pieter Jan Stappers. 2008. “Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design.” CoDesign 4 (1): 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875068.

Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) for the Co-Creation of Urban Green Spaces: A Research-Driven Approach to Local Knowledge and Community Engagement

Charalampos Spanos, Georgios Artopoulos, Constantinos Kritiotis, Afroditi Magou

Urban riverbed of the Pedieos River in Strovolos, Cyprus. Photo: authors

Nature-based solutions (NBS) integrate nature-inspired strategies to promote environmental, social, and economic sustainability. In this text, we present a roadmap for learning about the local participatory culture and the mentality around public green spaces through a case study of an urban riverbed in Strovolos, Cyprus – the Pedieos River – which has significant environmental and ecological importance for the urban environment, presenting new insights into co-creation approaches.

This was the first step in a novel co-creation workflow, including governmental and local authorities, NGOs, and local communities, in a process driven by local “living knowledge” where formal and informal barriers must be unlearned through the collaboration of different agencies and stakeholders. Diverse participatory methods were integrated in this workflow to engage underrepresented social groups, such as the elderly, youth, and children, while raising awareness of the importance of preserving biodiversity and promoting human-nature relationships. The methods we used include physical and digital interaction with nature and field explorations, open discussions based on information, and serious geo-games for scenario testing and decision-making. We also integrated citizen science tools into the process, aiming to encourage participants to share their knowledge, acknowledging that the local communities carry important “living knowledge.”

Nature-based solutions (NBS) offer an approach capable of transitioning our expanding urbanised environments to more sustainable, climate-adaptive, and inclusive futures. In this research, we moved beyond traditional disciplinary approaches to NBS by adopting a hybrid, integrated perspective, exploring the social and ecological complexities of developing just and sustainable NBS through prioritising citizens’ engagement in decision-making participatory processes and the inclusion of marginalised knowledge. The project TRANS-lighthouses, under which we conduct our research, aims to create a body of knowledge on participatory practices through the implementation of NBS and the formation of just, inclusive, and innovative co-governance models in pilot cases. It investigates tools and methodologies for citizen science in “co-diagnostic” phases, to form common understandings, establishing a living knowledge lab (LKL) as a first step for collaborative governance.

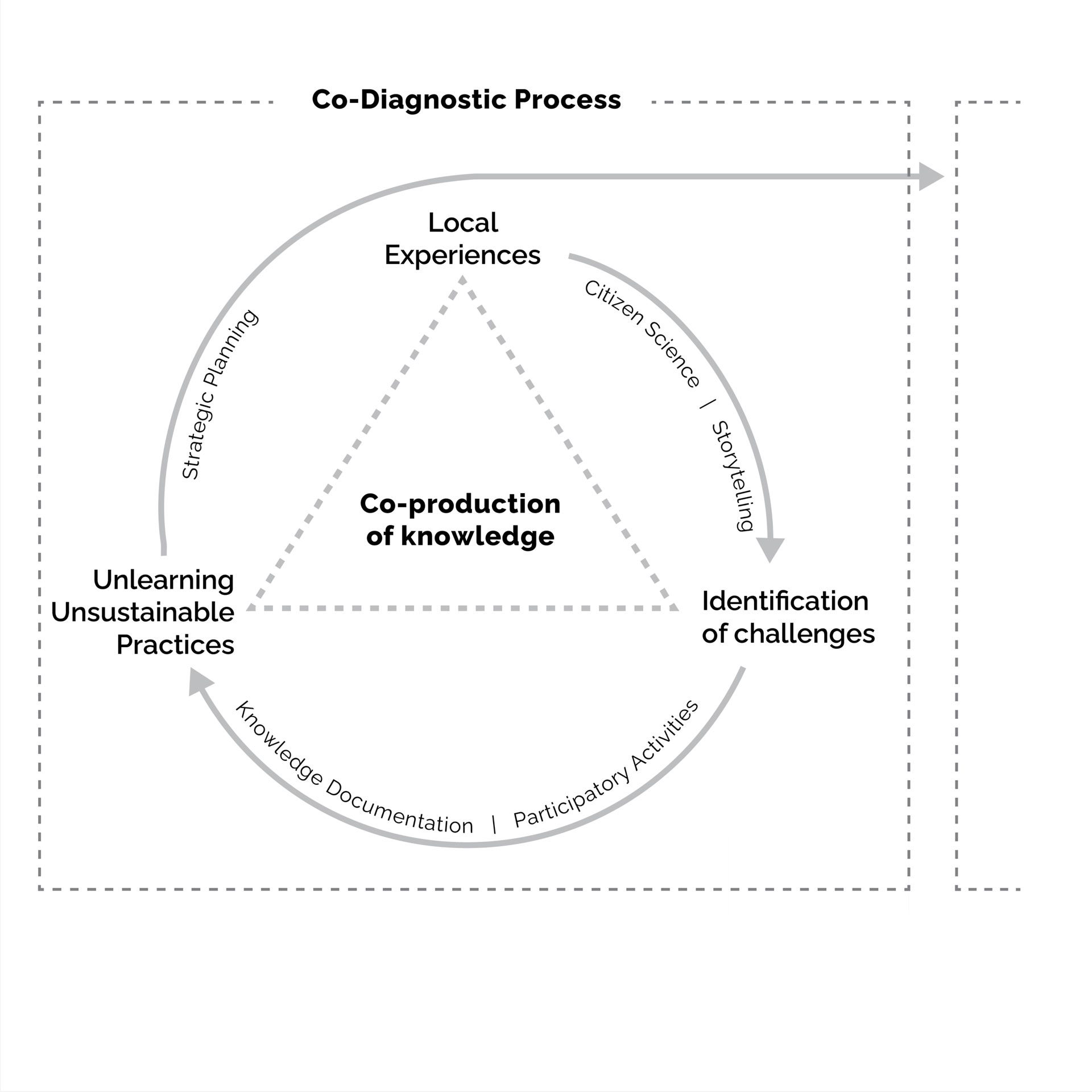

The co-diagnostic process was one of the early stages of action for establishing a Living Lab (LL). Co-diagnostic operations are meant to lead to the co-production of knowledge, defined by Norström et al. (2020) as “Iterative and collaborative processes involving diverse types of expertise, knowledge, and actors to produce context-specific knowledge and pathways towards a sustainable future.” A structured co-diagnostic methodology facilitates the transition to sustainable urban practices by reassessing and discarding outdated behaviours (Tsang & Zahra 2008). The Strovolos case study demonstrates how citizen engagement, knowledge co-production, and unlearning processes can contribute to sustainable urban governance.

The research by UNaLab (2019) explains that stakeholder engagement is a process of engaging people who “affect or are affected” by a decision, suggesting that the level of engagement of each stakeholder may vary throughout the timeline of a project based on their different interests, so it is thus essential to have all actors informed on all the processes and activities of the project. Similarly, the study PHUSICOS (2018) identified critical challenges and success factors for LL’s, including establishing a “clear, common, and accessible project terminology”, creating a strong “social inclusiveness and stakeholder representation,” professionally facilitating participation with early on and systematic design, as well as achieving an “iterative knowledge exchange.” Building on these insights, our study in Strovolos adopts a co-diagnostic methodology that emphasizes stakeholder engagement in decision-making, focusing initially on the involvement of the municipal government, followed by local associations and institutions to create synergies with other local projects, and later the involvement of kids, elderly and the community through targeted meetings and outreach activities (Caitana and Moniz 2024, 8; URBiNAT 2019, 262). This multi-scalar stakeholder network was designed to foster the co-production of knowledge and facilitate discussions to identify unsustainable practices for potential unlearning.

The co-diagnostic approach provides a platform for learning and unlearning, ensuring the legitimization of community knowledge and experiences, as well as the adaptation of new beliefs (Nygren, Jokinen, and Nikula 2017).

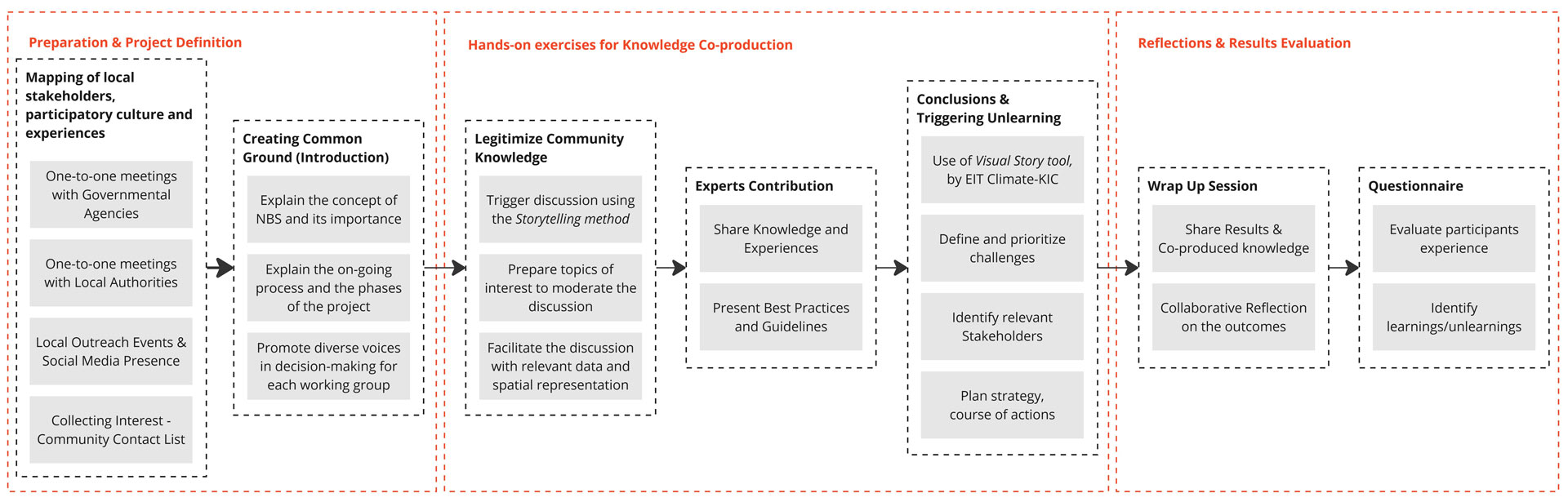

Conceptual diagram of co-diagnostic approach followed for the co-production of knowledge

Through a structured mapping exercise, we identified local key stakeholders to engage with the co-diagnostic activity in a workshop that served as the initial phase for establishing a LL in Strovolos Municipality, which aims to co-govern the implemented NBS. Our methodology included specific tools to enhance collaborations and was organized into three main phases. The first phase of the co-diagnostic process involved the preparation and the project definition, namely the mapping of the local participatory culture. During this first phase, one-to-one meetings were conducted with governmental and municipal agents, as well as with relevant NGOs and local groups and associations. In parallel, the research team participated in local outreach events to promote the project and its objectives, while establishing a social media presence for communication purposes. This first phase also informed the project on local challenges deriving from the interaction with citizens and the authorities, providing valuable information that was considered for structuring the co-diagnostic workshop.

The second phase consisted of the implementation of a co-diagnostic workshop, during which 31 participants – encompassing NGO representatives, city council members, municipal officers, and local residents – engaged in activities designed to encourage knowledge co-production. We separated the participants into three working groups, Biodiversity & Environment, Public Space & Activities, and Mobility & Accessibility, each of which followed a three-session workflow with exercises supported by specific tools. The first exercise aimed at legitimising community knowledge, informed by the information collected before the workshop. The participants were provided with pre-scripted stories of fictional personas to stimulate discussions, that were documented in fill-in templates by formulating specific topics to navigate the conversation. All three sessions were supported with data boards and a 360° video of the area of the Pedieos River to trigger opinions and ideas. The second session invited the experts to share their experiences and knowledge with the community on the topics of the working groups. This exercise aimed at revealing unsustainable practices by the community and learning from best practices examples. The final session encouraged the working group to reflect upon the preceding discussions, prioritize the challenges related to their topic, and form a strategy to address the most important issues, using the EIT Climate-KIC Visual Story tool (De Vicente Lopez and Matti 2016, 118–21).

The final phase of the co-diagnostic activity involved a wrap-up session that took place at the end of the workshop and consisted of the presentation of each working group’s Visual Story to the rest of the participants by the moderators of each team. After each presentation, there was time for suggestions and questions, allowing for more contributions, and each workshop participant was informed of the conclusions and reflections of the different working groups.

Visual Stories presented by representatives of each working group. Photos: Authors

Finally, the table below provides a visual representation of the aforementioned steps and tools of the co-diagnostic workshop methodology.

Co-diagnostic workshop methodology to trigger unlearning for NBS implementation

Unlike conventional top-down urban planning which often marginalises local knowledge, inclusive NBS emphasize participatory co-creation that includes local voices and experiences. The Strovolos case study demonstrates how this bottom-up approach could foster more resilient and adaptive urban ecosystems. The co-diagnostic workshop achieved the inclusion and documentation of marginalised knowledge by the elderly, youth, and people with disabilities, as well as the introduction of experts into the discussion, to eventually co-create inclusive NBS scenarios. During the workshop, each working group elaborated on the local participatory culture and decision-making procedures, expressed the importance of stakeholder engagement, and called for action towards raising awareness about local environmental challenges. The use of the Visual Story tool has contributed to a common understanding of the complexity around strategic planning, acknowledging that identifying specific challenges and prioritising and strategizing action, requires not only collaborative efforts but also commitment and ownership of the process.

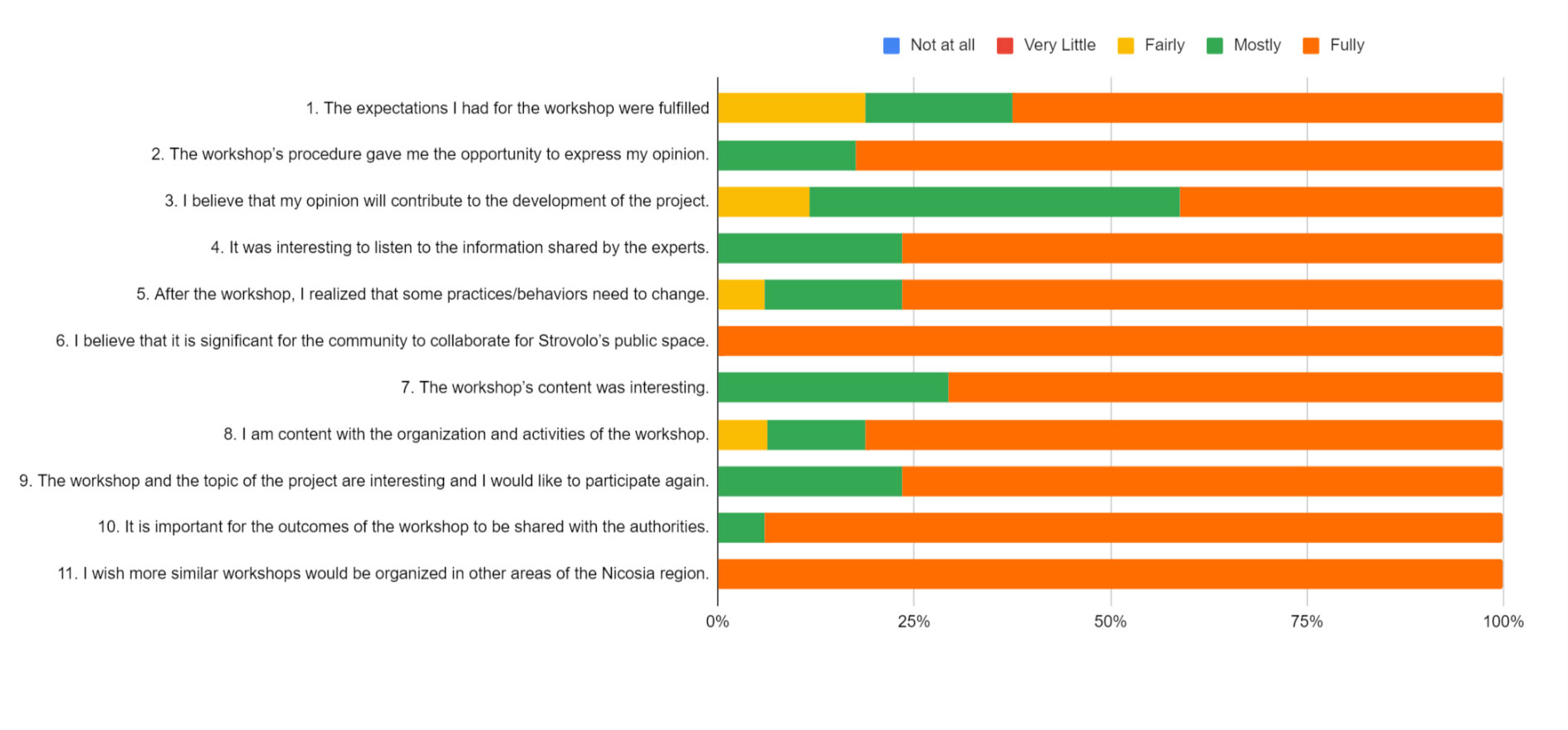

Methodologies for participatory governance developed feelings of responsibility and belonging within the community, as made evident from the anonymized responses to the questionnaire that was distributed and completed by 17 of the 31 participants. Their feedback (fig.4) suggests that all the respondents acknowledged the significance of community engagement in the decision-making concerning the public space of Strovolos, with most of them realising the need to change some practices and behaviours, such as caring for all the species and not just stray cats, as well as respecting the needs of diverse social groups. Overall, the expectations of the community were fulfilled during the workshop, with several suggesting future activities related to expanding learning about NBS, discussing the heritage of Strovolos, and exploring solutions to the challenges identified.

Outcomes of the questionnaire distributed after the workshop completion

Cyprus is characterized by limited opportunities for public engagement, mainly consisting of public deliberations (Trutkowski, Del Bianco, and Loizou 2017), which leads the community to feel undervalued and overlooked. In this context, our approach showed that structured methodologies on participatory urban planning for NBS can empower the community, legitimize their knowledge and experiences, and importantly, involve them in decision-making processes.

The co-diagnostic workshop on Strovolos case study, highlighted the essential role of democratic and inclusive decision-making in NBS implementation, combining local knowledge with expert input, and establishing a foundation for a LL in the area. Involving a diverse range of stakeholders, including local authorities, NGOs, and community members, the workshop marked an initial step toward the co-governance of the implemented NBS in the Linear Park. In Cyprus, where centralized governance often limits local autonomy, this initiative showcased the potential for participatory urban planning, despite a generally low participatory culture. Through structured dialogues and tools, participants developed shared understandings and strategies prioritising environmental awareness, accessibility, and public space safety. This co-diagnostic process underscores the importance of integrating marginalized voices into sustainable urban planning, setting the groundwork for future agile NBS co-governance models, and fostering equitable, resilient urban environments. The study highlights the transformative potential of participatory NBS in fostering sustainable urban governance, however, realising these outcomes require continued commitment from policymakers, researchers, and communities. Future research should explore how NBS frameworks can be institutionalized within policy structures, ensuring that participatory decision-making translates into long-term urban resilience.

Acknowledgements

This research is conducted under the framework of TRANS-lighthouses, a European-funded Horizon Project (grant agreement no. 101084628)

References

Caitana, Beatriz, and Gonçalo Canto Moniz. 2024. “Co‐Production Boundaries of Nature‐Based Solutions for Urban Regeneration: The Case of a Healthy Corridor.” Cogitatio 9 (Urban Planning). https://doi.org/10.17645/up.7306.

De Vicente Lopez, Javier, and Cristian Matti. 2016. Visual Toolbox for System Innovation. A Resource Book for Practitioners to Map, Analyse and Facilitate Sustainability Transitions. Transitions Hub Series. Brussels: Climate-KIC.

Norström, Albert V., Christopher Cvitanovic, Marie F. Löf, Simon West, Carina Wyborn, Patricia Balvanera, Angela T. Bednarek, et al. 2020. “Principles for Knowledge Co-Production in Sustainability Research.” Nature Sustainability 3 (3): 182–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0448-2.

Nygren, Nina V., Ari Jokinen, and Ari Nikula. 2017. “Unlearning in Managing Wicked Biodiversity Problems.” Landscape and Urban Planning 167 (November):473–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.06.019.PHUSICOS. 2018. “Guiding Framework for Tailored Living Lab Establishment at Concept and Demonstrator Case Study Sites, Deliverable D3.1.” TUM. https://www.phusicos.eu/.

Trutkowski, Cezary, Daniele Del Bianco, and Eleftherios Loizou. 2017. “Training Needs Analysis of Local Government in Cyprus.” Council of Europe: Centre of expertise for local government reform.

Tsang, Eric W.K., and Shaker A. Zahra. 2008. “Organizational Unlearning.” Human Relations 61 (10): 1435–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726708095710.

UNaLab. 2019. “STAKEHOLDERS AND TARGET GROUPS, Deliverable D7.1.” Comune di Genova & ERRIN. https://unalab.eu/en.

URBiNAT. 2019. “Local Diagnosis Report for Each Frontrunner City, Deliverable D2.1.” IULM. https://urbinat.eu/.

Learning from Islamic Tradition: Changing the Perception of Public Space

Abeer Allahham

Public space refers to spaces “provided especially by the government for the use of people in general” (Crowther 1995). They are mostly perceived in contemporary capitalist societies as neutral, democratic, egalitarian, and all-inclusive spaces. However, this idealized perception of public space is in stark contrast to actual reality. As argued in this paper, public spaces are not neutral; they are inherently political entities influenced by power relations.

With the advent of the modern state, which is based on concepts of sovereignty, legitimacy, representation, and power, public spaces underwent significant transformations. To materialize its sovereignty and expand its power, the state, since the second half of the nineteenth century, appropriated all non-private properties (i.e., streets, plazas, railroads, not-owned lands) as well as the infrastructure and other related services and designated them as “public” properties, owned and controlled by the state as a representative of the “public” (Allahham 2015). The dichotomy of “public-private” space was instituted. Public space became a space of power manifestation where the state can exercise its sovereign power and rights of ownership and control over the public and public space. This dual role of the state as a sovereign and a landlord creates a tension. On one hand, the state claims to represent the public’s interests, but on the other hand, it owns and controls public spaces as a property owner. This duality means that the state holds not only legislative authority but also property rights, enabling it to control access to and activities within public spaces.

This change gave the modern state a legitimate cover to intervene in and control the built environment and restructure its related rights. Public space turned to be an instrumental space to reach certain ends. In this sense, public spaces are not merely areas for social interaction, but territories where power is both exercised and contested.

Exploring the intersection of power, rights, and public space, this paper critically examines how public spaces are perceived, regulated, and controlled by the state. The paper introduces the traditional Islamic built environment as an alternative to the existing capitalist model, where public spaces were shared spaces among community members and groups. Territories were not sharply divided into public and private spaces, as is the case in the modern capitalist city. The paper calls for broadening spatial concepts in architectural education to learn for envisioning alternatives to the modern city.

Territory and boundary are central concepts in understanding how the state exerts control over public space. Territoriality, as Sacks defines it (Sack 1986; 2000), is a spatial strategy used to control people and things by controlling the area or territory. Foucault views territoriality as a means of domination and control (Foucault 1975, cited in Cornwall 2002). It is a spatiality of power which many scholars consider as one precondition of state power (Paasi 2003).

To delineate its power and control over space (including public space), the modern state adopted a territorialization strategy, where definite boundaries of public and private territories were drawn, legally and spatially. Through territories, the state can control the social (people) and the spatial realms. Hence, territories are spatio-political constructs that define inclusion and exclusion, dictating who has access to which spaces and under what conditions.

The state, as a landlord has the right of exclusion or the right of “privacy”, whereas for the public, being the party represented by the state, public space denotes an ideal of access to all members; to enjoy the right to be included or the right of “publicity” (as used by Kilan 1998). These two visions towards public space (claiming rights of privacy and of publicity) is a matter of contestation.

Territorial boundaries delineate uneven distribution of power where power is concentrated in public spaces and dispersed in a lesser form in private territories. As public territories’ spatial boundaries resulted from the power game, they are unchallengeable; they are outside the territory of possibility, a matter that sustains the hegemonic perspectives of public space. The contestation thus arises at the level of the state as a landlord.

Public space became an “invited space” (Hayward 2004), where users are viewed as guests with rights of access for specific “appropriate” purposes. Contestation as to who owns public space (Hoidn 2016), the publicness of public space, or as Madanipour asked in the title of his book “Whose public space?” surfaced (Madanipour 2010). These calls often fail to challenge the fundamental power structure that defines these spaces. Instead, they tend to focus on issues like accessibility, exclusion, and spatial justice without addressing the power mechanisms in and of public space. They are rights-based territorial claims that involve taking action to shift the boundaries of what is considered possible. In that sense, the social (and not the spatial) boundaries are the matter of contestation; or the “territories of possibility.” They are constantly negotiated and defied, thus susceptible to be “reterritorialized.” Such calls are considered partial; they are subject to the state’s power game, thus direct their goals and claims to avoid touching on the untouchable; the state’s scopes of power. These calls have reached an impasse, yet, is there an alternative?

As explored above, the modern capitalist city relies on rigid public-private boundaries, reinforcing state control over public spaces. But is this the only model? Examining historical alternatives, particularly the spatial structures of traditional Islamic cities, reveals a different paradigm; one that challenges the very foundation of state-controlled public space.

Comparing the territorial structure of the modern city and its network of boundaries with that of traditional Islamic cities, one may argue that two reasons are driving the contestation over public space: first, the state’s dual role as a sovereign and landlord, and second, the distinctness of territorial boundaries (as a symbol of power) between private and public space. The binary of public-private, as well as other binaries identified in related literature, such as inclusive-exclusive, accessible-restricted, open-closed, invited space-claimed space, and power-rights are clear manifestation of this tension. Alternatively, if viewed through the non-capitalist lens of traditional Islamic cities, where the aforementioned two issues do not exist, such tensions will not arise.

To start with, the concept of public space, as it exists in modern capitalist societies, does not apply to traditional Islamic cities. The territorial structure of traditional Islamic cities is made up of a group of contiguous and overlapped spaces or territories known as (khitat) (singular khitta), where each khitta is owned and controlled by a certain party. The house is a private khitta; the dead-end street with its adjacent houses that open onto it forms a larger territory owned and controlled by the house owners as a party; and a number of dead-end streets constitute a larger territory, such as the neighborhood (hara). Khitta or territory, as used by historians in their manuscripts about Islamic cities, is indicative of control; it is a defined area of influence controlled and managed by a specific party (Akbar 1987; 1988).

Territorial structure (khitat) in an old district of Tunisia. Each circle roughly represents a khitta. Drawing by the author.

In this sense, most territories in Islamic cities (including open spaces) were owned and controlled by the people themselves without any intervention from the higher authorities, socially and spatially. The Islamic city can be visualized as comprised of relatively independent spatial territories (khitat), however, they are overlapped due to the overlapping circles of their respective spatial and social rights. For example, a dead-end street is collectively owned by its inhabitants, with decisions about its use and maintenance are made by its owners. This model contrasts sharply with the modern capitalist city where public spaces are owned and controlled by the state, and boundaries are sharply defined.

As part of the modern state’s political strategy to reify its power and sovereign, territorial boundaries constituted an essential component in the territoriality strategy employed. Sharp demarcated boundaries created a two-level territorial structure, public and private, socially and spatially, characterized by shallow depth; a crucial condition that guarantees the state’s control over space and people. Conversely, as the territorial structure of the Islamic city is rights-based, territories in Islamic cities were overlapped and encircled, with no definite boundaries between them. Each territory encloses smaller territories that contain smaller territories, and so on. The same hierarchy applies to the social territorial layer of the built environment. The party of the smaller territory is a partner in the party of the larger related territory (e.g. alley), which is in turn a partner in the party of the larger territory (through street), thus has the right to participate in its production and reproduction. Similarly, the deeper dead-end street as a territory is included in the territory of the outer dead-end street, spatially and socially. This overlapping territorial structure of traditional Islamic cities allowed for a more entangled relationship between space and society. Public space is not a tool of state control, but a shared space managed by the community. Hence, the power-based modern classification of spaces into public, semi-public, semi-private, and private does not apply to traditional Islamic cities.

Public space in modern capitalist societies is a product of power and serves as a critical territory for the exercise of state control. The state’s dual role as both sovereign and landlord allows it to maintain authority over public spaces, controlling access, behavior, and rights within these spaces. The contestation over public space is deeply rooted in the territorialization of power that defines the modern capitalist city, rather than social rights or accessibility as most calls to reclaim the public space emphasize.

The paper recommends broadening the perception of public space by incorporating issues of power and rights into its un-learnings and learnings. It suggests that an alternative model of public collective space, like that found in traditional Islamic cities, could offer a way to move beyond the tensions and contestations that define modern public spaces. In this model, the integration of social and spatial structures, and the absence of a rigid public-private dichotomy, allowed for more equitable and cooperative use of space.

Going beyond the tensions and paradoxes that define modern public space, architectural education must critically engage with alternative spatial paradigms. Traditional Islamic cities offer historical insights and strategies for designing urban environments that prioritize community agency over state control. Rethinking public space through different lenses paves the road for learning to design for more inclusive and just urban futures, where public space truly belongs to the people.

References

Akbar, Jamel. 1987. “Khatta and the Territorial Structure of Early Muslim Towns.” Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture 6: 22-32.

Akbar, Jamel. 1988. Crisis in the Built Environment: The Case of the Muslim City. Concept Media, Singapore.

Allahham, Abeer. 2015. “Rethinking the Concept of the Neighborhood: An Enabling or a Housing Model?” International Journal for Architectural Research, Archnet-IJAR 9 (2): 152-169.

Cornwall, Andrea, Making Spaces, Changing Places, Situating Participation in Development. IDS working paper 170 Brighton, 2002.

Crowther, Jonathan, eds. 1995. Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

Hayward, Clarissa. 2004. De-Facing Power. Cambridge University Press.

Hoidn, Barbara. Eds. 2016. Demo Polis: The Right to Public Space. Park Books, Zurich.

Kilan, Ted. 1998. “Public and Private, Power and Space.” In Philosophy and Geography II: The Production of Public Space, edited by A. Light. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Maryland.

Madanipour, Ali, eds. 2010. Whose Public Space? Routledge, London.

Paasi, Anssi. 2003. “Territory.” In A Companion to Political Geography, edited by J. Agnew; K. Mitchell; and G. Toal. Blackwell, Oxford.

Sack, Robert D. 1986. Human Territoriality; its Theory and History. Cambridge University Press.

Sack, Robert D. 2000. “Classics in Human Geography Revisited.” Progress in Human Geography 24 (1).

Learnings /Unlearnings: Environmental Pedagogies, Play, Policies, and Spatial Design responds to the call Designed Living Environment—Architecture, Form, Design, Art and Cultural Heritage in Public Spaces, and is funded by Formas—a Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development with the Swedish National Board of Housing, Building and Planning; ArkDes; the Swedish National Heritage Board; and the Public Arts Agency Sweden, under the grant agreement number 2020-02402.

Thank you to Färgfabriken in Stockholm, especially to Karin Englund and Anna-Karin Wulgué for hosting Learnings/Unlearnings.

1.

ADAPT2SDG is a Decolonised Architectural Pedagogical Typology coined by Ashraf M. Salama, Lindy Osborn Burton and Madhavi Patil. It is being articulated for publication in the Journal of Architecture in 2025.

, PhD, is Chair in Architecture and Urbanism and Head of the Department of Architecture and Built Environment at Northumbria University, Newcastle Upon Tyne. He co-directs the UIA Education Commission and served as co-Reporter of the UNESCO/UIA Validation Council for Architectural Education. An honorary Professor at University Putra Malaysia, he received his education at Al Azhar University in Cairo and North Carolina State University. Salama has chaired four architecture schools in Egypt, Qatar, Scotland, and England, secured over £2.5 million in research funding, and authored 17 books and numerous publications. He is Editor-in-Chief of Archnet-IJAR and has been a jury member for several global competitions. He received the UIA’s 2017 Jean Tschumi Prize for Excellence in Architectural Education and Criticism.

Schade is a dedicated urban planner committed to creating sustainable and inclusive living spaces. With a background in Sustainable Urban Planning and Design at KTH Royal Institute of Technology, she enjoys merging theoretical concepts with hands-on approaches, aiming to design future-proof spaces through participatory formats and creative-artistic-methods

is an architect and urbanist and currently Assistant Professor at the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Italy. He received his PhD from the Universitat Politecnica de Valencia in 2020. Mustapha studied architecture and philosophy and has been involved in teaching in Lebanon, China, Germany and Italy. He has also worked professionally, building and winning competitions all over the world. His research focuses primarily on understanding the complex socio-cultural dynamics in urban environments while examining the existential well-being of city dwellers. He is committed to exploring the future and exploring alternative urban possibilities.

is teaching/researching in the transdisciplinary and practice-based MA Eco-Social Design. With students, teachers/researchers and partners from neighbourhoods, agricultures, sciences and activism, he is co-creating design practices, tools and structures that contribute to social-ecological transformations towards more solidary and sustainable modes of living and production. For this he is trying to draw things, ideas and actors together, among others when curating the annual conference By Design or by Disaster → blog, contributing to the regional Climate Citizen Assembly, Climate Action, KAUZ – Laboratory for Climate Justice, Work and Future, New European Bauhaus of the Mountains, the research cluster trans–form, Scientists for Future South Tyrol, Zukunftspakt–Patto Futuro, and lab:bz.

is a Research Assistant at the Virtual Environments Lab of The Cyprus Institute where he conducts his PhD research that focuses on developing digital tools to support community engagement on the planning of public spaces within historical neighbourhoods, with an emphasis on integrating Nature-based Solutions (NBS) to address environmental challenges.