Diffractive spatial practices for urgent pedagogies

Socrates Stratis

CATEGORY

“Then, ‘urgent pedagogies’ create a shared language across material cultural practices. They facilitate the creative confrontation of multiple and divergent sources of knowledge. They generate a complex system of synergies between different sources of knowledge production and learning environments”.

What if “urgent pedagogies” employ diffractive spatial practices to provide means in transforming conflicts constructively and creatively? Then, they would support conflict that involves the political in democratic spatial practices while resisting conflict that is associated with hegemonic forms of violence.

Let’s talk about “Countering the Cyprus Militarization” as a part of my diffractive approach in architecture. It could be a pertinent example to discuss how urgent pedagogies could provide means to transform conflicts constructively and creatively, thanks to diffractive spatial practices. The Cypriot context condenses many facets of hegemonic domination that produce forms of conflict associated with violence. The complexity of such context reminds us of the limitations of architecture in countering hegemonic domination. It urges us, in other words, to reach out to interdisciplinary collaborations to re-establish a critical urban approach. The objective of “Countering the Cyprus Militarization” has been to create a critical stance regarding the over militarized condition of the island. It has been about co-creating imaginaries for shared futures for citizens of deeply divided societies, offering them means to imagine everyday little utopias.[1]

Referring here to the term Diffraction as a physical phenomenon is engendered when a multitude of waves run into an obstacle along their trajectory, and sometimes they overlap. Diffraction is employed metaphorically in contemporary feminist theory standing for ways consciousness and thought are both attentive to difference and critical. According to Karen Barad, diffraction patterns can be understood as the basic ingredient that constitutes the world.[2]The metaphor of diffraction is also used by Donna Haraway to replace that of reflection. She argues that diffraction entails a complex and dynamic process that implies the creation of ‘different patterns in the world’. Reflection, on the other hand, entails a mirror as a critical tool. Consequently, it involves the reproduction of the static logic of the same, somewhere else.[3] “Seeing and thinking diffractively, therefore, implies a self-accountable, critical, and responsible engagement with the world”.[4] It is about a dialogical manner of engagement that brings about unexpected and creative outcomes. The debate regarding spatial practices for change increasingly involves the metaphor of diffraction through the lens of new materialism.[5]

Conflict is an expression of the heterogeneity of interests, values, and beliefs that arise when new formations generated by social change come up against inherited constraints.[6] Both the political aspect of democratic practices but also hegemonic forms of violence are associated with conflict. We can consider conflict a mode of shaping the city and its citizenship but at the same time a danger for corroding citizenship and the urban environment. “Countering the Cyprus Militarization” is manifested through practice, writing, curating as well as pedagogies. It is about entanglements between practice, theory and politics. More precisely, it engenders creative and unexpected relations between the disciplinary profession of architecture and its political ramifications, between academic and non-academic environments, between being in the city and thinking of the city. Such entanglements imply a ‘self-accountable critical, and responsive engagement with the world.[7]

Entanglements have taken place thanks to my immersion within the hostile Cypriot conflictual environment, hand-in-hand with the rest of the participants. By being together, trust and continuity are sustained among the participants, encouraging different kinds of situated knowledge to emerge. By being together, I am encouraged to take risks while manipulating my power as a tenured professor at a public university of the Republic of Cyprus.

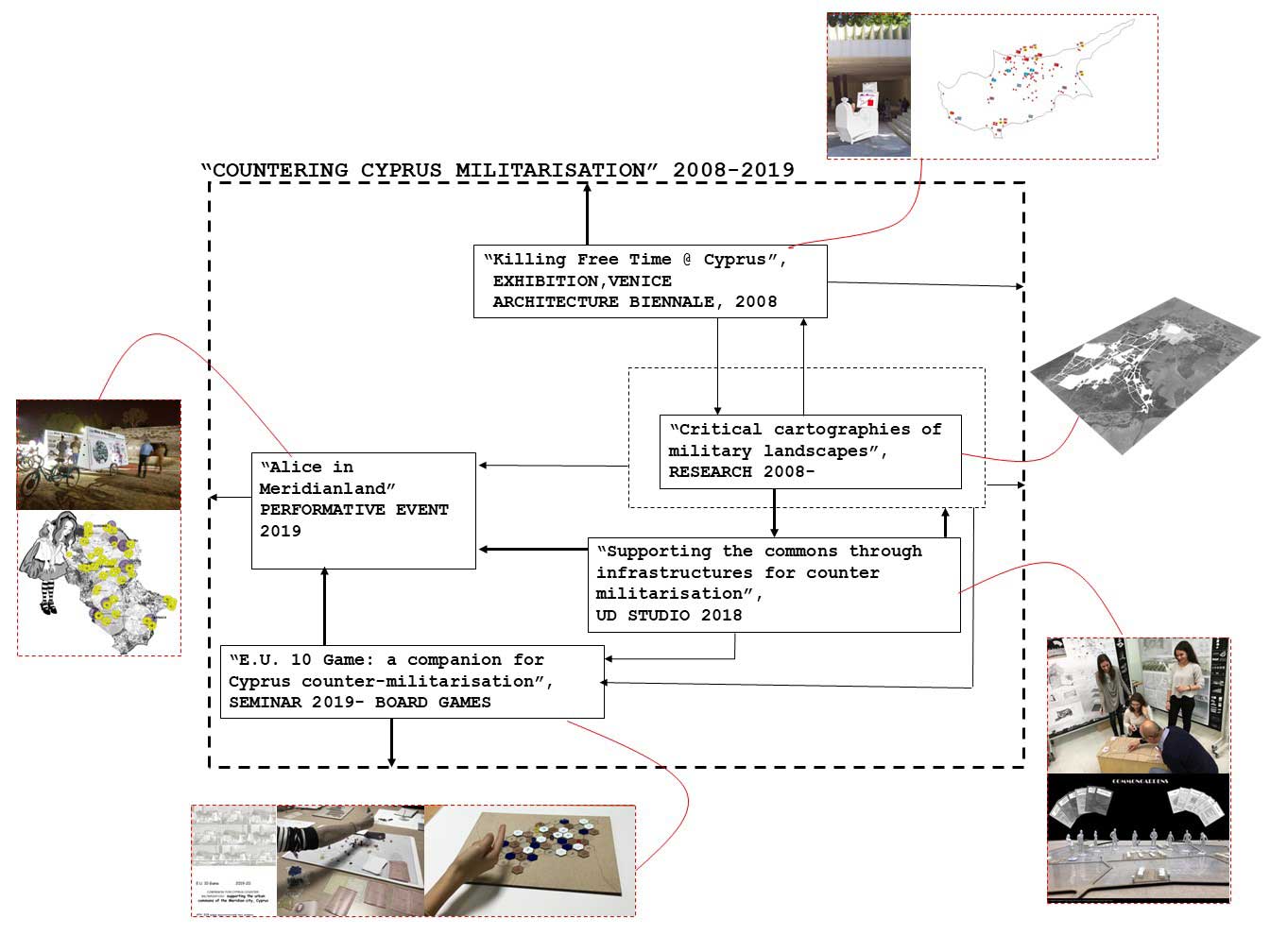

The five projects that constitute “Countering the Cyprus Militarization” are: “Killing Free Time @ Cyprus”, “Critical cartographies of military landscapes”, “Supporting the commons through infrastructures for counter-militarization”, “EU 10 Game: a companion for Cyprus counter-militarization”, and “Alice in Meridianland”.

Countering the Cyprus Militarization 2008 – 2019. Image courtesy of Laboratory of Urbanism, University of Cyprus (LUCY).

Further below, I will unpack the potential agencies of “urgent pedagogies” as a diffractive spatial practice by formulating suggestions in a manifesto-like format, based on the principles of the aforementioned five projects – principles that constitute my agonistic spirit for architecture. Between the lines of the “what if” / “then” manifesto, I insert brief descriptions of the five projects. These are placed with a different typeset and font color. In other words, you can read the article in its entirety, or you can choose to skip one of the two parts. At the same time, associations may emerge between the two parts of the article depending on the manner the reader chooses to proceed with the reading.

What if one of the main principles of “urgent pedagogies” is the confrontation of states of exception? Keller Easterling finds rather compelling Giorgio Agamben’s argument that the condition of the camp as a place of legal exception can be normalized as a political paradigm that appears in the “zones d’attentes” of our airports and certain outskirts of our cities”.[8] The notion of “state of exception” according to Keller Easterling, is an important agent in shaping the neoliberal city. Keller Easterling draws familiarities in terms of seeking immunity as a condition of exceptions between the architecture of warfare that is visible in detention camps, crossings of borders and military bases with the free trade zones, residential golf club developments, tax shelters, and data havens, in other words, the architecture of the neoliberal city.[9]

What if “urgent pedagogies” unveil islands “entitled to special sovereignty and exemption from law”? [10].

Then, “urgent pedagogies” is about undermining states of exception by practices of counter-mapping thus, supporting conflicts that are associated with the political in democratic practices.[11]

Then, one of the priorities of “urgent pedagogies” is to support the city in regaining its historical capacity to transform conflicts. There is a worrying decrease in such capacity due to ethnic and social cleansing, class wars and asymmetrical wars. To transform conflicts into openness, according to Saskia Sassen.[12]

Then, to employ such a priority, “urgent pedagogies” would need to support the production of presence instead of the protection of property in the city, according to Saskia Sassen. The production of presence by the powerless with politics, in claiming the right to the city. Thanks to the urban practices of those without power, there is a constitution of new forms of political subjectivity, (ie. citizenship).

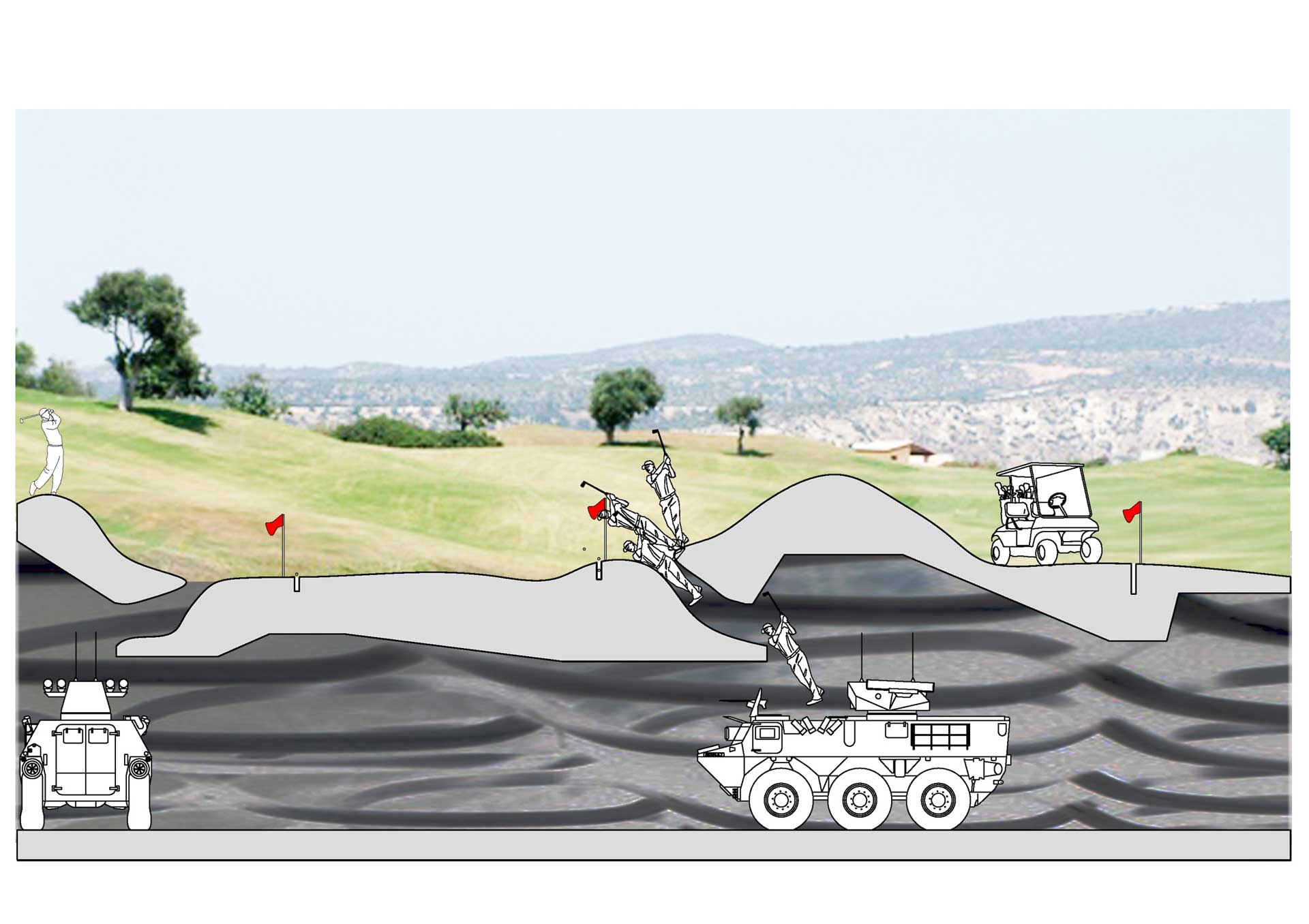

The “Killing Free Time @ Cyprus” project (Venice 2008)[13] is the contribution to the Cypriot Pavilion at Venice Biennale of Architecture. It is a critical stance regarding the military architectural heritage on the island. It comments on the uncanny proximity between the tourist industry and militarized territories in Cyprus. It involves an alternative tourist planner platform that invites users to choose active or historic military infrastructures as a tourist destination. The user’s choice of risk (low, medium, high) transforms, accordingly, her/his destination, entangling in uncanny manners, landscapes of relaxation with those of war.

The sense of irony becomes a design tool for the disempowered.

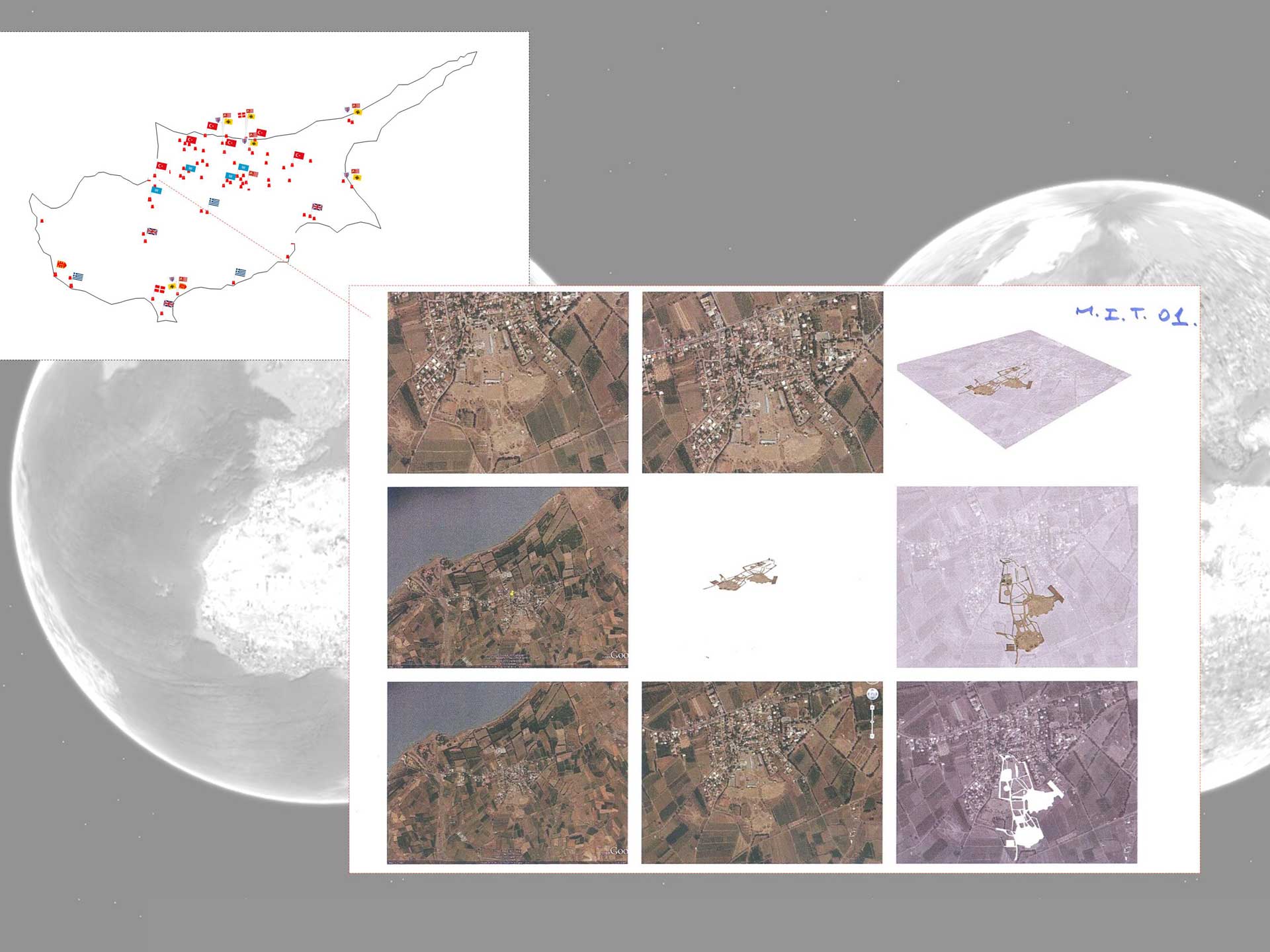

The “Critical cartographies of military landscapes” project (2008 –) [14] involves on-going research about mapping the transformation of civilian and natural landscapes by the military infrastructures, especially those of Turkey. Furthermore, it documents how the spatial practices of Cypriots cope with the actual militarization of the island.

Counter-mapping the processes of territorialization of military regimes.

What if “urgent pedagogies” are the agent of the political spaces at the everyday level, where resistance may start from? Richard Sennett argues that the everyday political space supports the creation of ‘socially skilled’ people. People who know how to deal with the other, quite often coming from areas across divides. People who gain urban subjectivity. The fading of such spaces reduces the possibility of having ‘socially skilled’ citizens. The globalization processes of neoliberalism shrink the political spaces at the everyday level, where resistance may start. ‘Calculative discourses’ that have to do with zoning and ‘smart city’ planning and the like, generate all sorts of spatial segregation in the cities.[15]

Then, “urgent pedagogies” empower spaces of resistance and co-operation that take place in spaces with porous borders, allowing for everyday exchange among people of difference in ethnicity or religion or social status.[16]

Then, “urgent pedagogies” develop practices of care for the creation of socially skilled people.

Then, “urgent pedagogies” is about thresholds. Thresholds connect and disconnect at the same time. They destroy the homogeneity and continuity envisioned by modernity and become agents for comparing differences without having them collapsed. Porous edges become thresholds according to Stavros Stavrides.[17] Thresholds become active catalysts in processes of reappropriating the city as commons. Urban thresholds regulate passages, thus indicating movement towards otherness.[18]

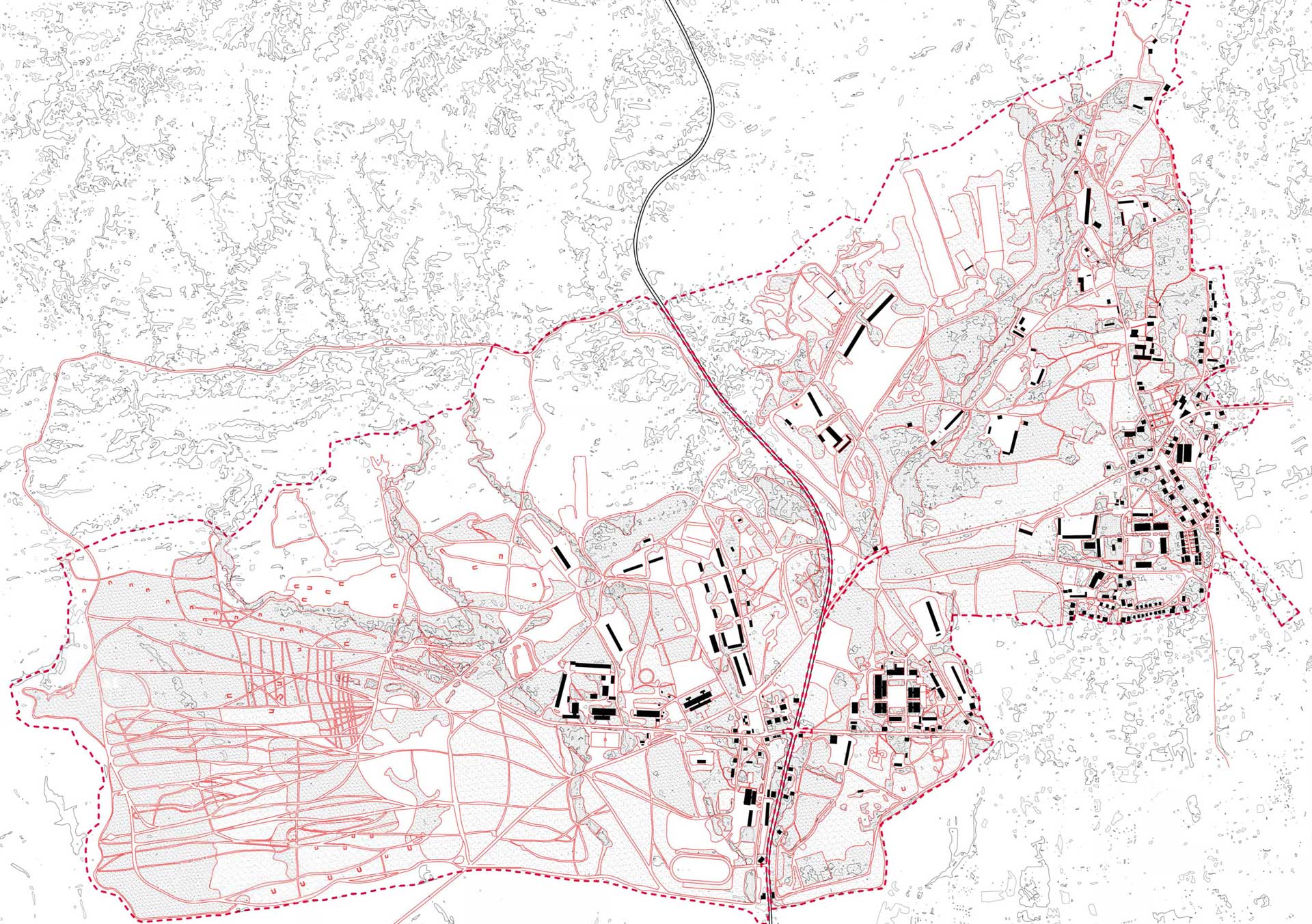

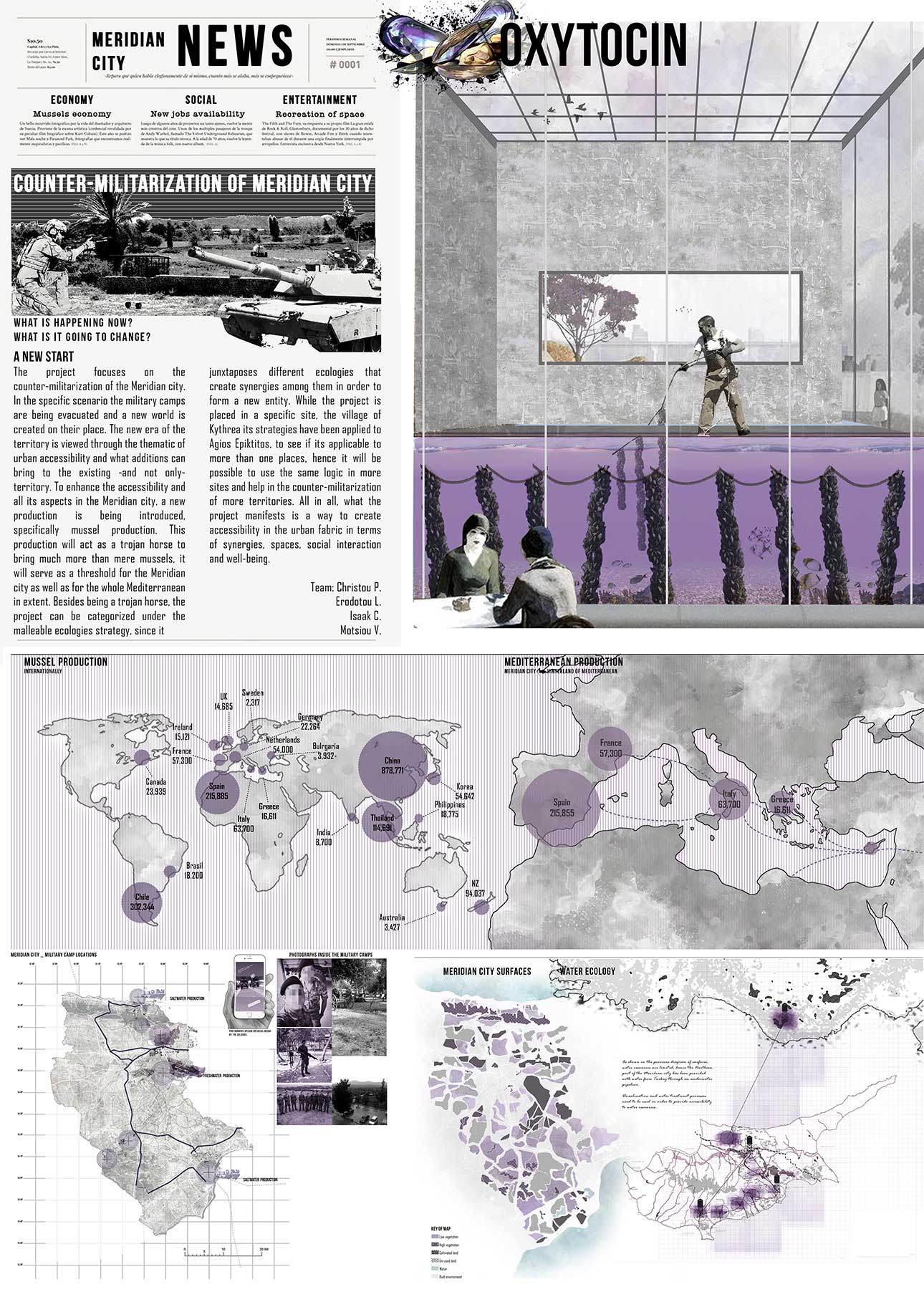

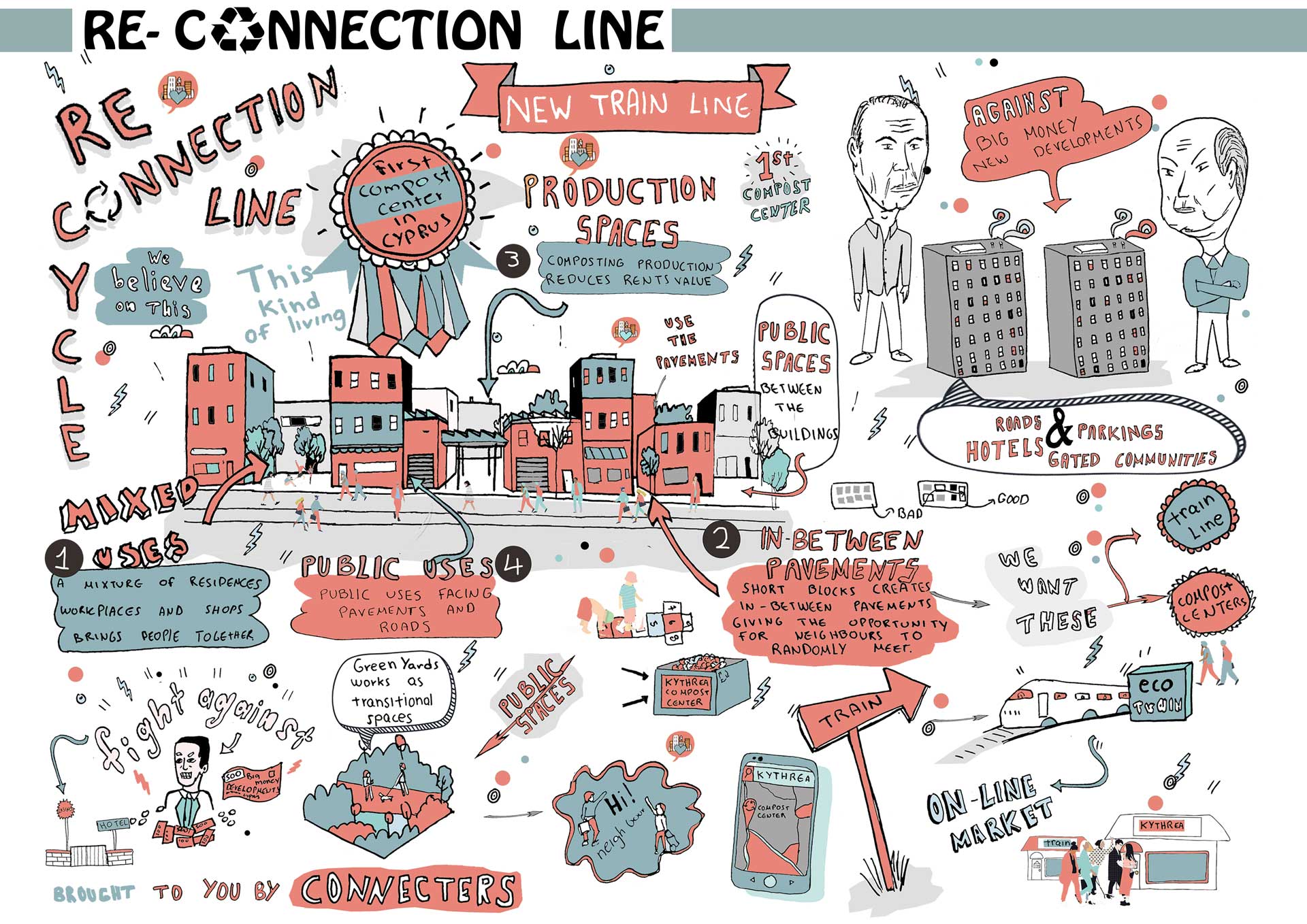

“Supporting the commons through infrastructures for counter-militarisation”, (2018) [19] is an urban design pedagogical project for the third-year undergraduate students of architecture at the University of Cyprus.

How can urban design support the commons in the scenario of Cyprus’ reunification, when the neoliberal model of urban reconstruction will prevail?

“Meridian City” or “Meridianland” is an imaginary city, yet a potential regional city, which will stretch across the island from the northern sea coast of Kyrenia to the southern coast of Larnaca.

Imaginative scenarios organize the urban design studio’s approach allowing for the students to imagine alternative shared futures for a web of areas in Meridianland that are occupied by military infrastructures.

The right to dream is utterly crucial for students immersed in a half-century deadlock due to a frozen conflict.

Oxytocin, Urban Design studio project. Image courtesy of, L. Herodotou, C. Isaak, V. Motsiou, Ch. Petrou.

Re-connection Line, Urban Design studio. Image courtesy of M. Mattheou, P. Sofokleous, A. Xenofontos, K. Xihilou.

What if the pedagogies in architecture didn’t involve the exclusive disciplinary order but the inclusive agency of spatial practices?.[20]

Then, “urgent pedagogies” bring forward what architecture does rather than what architecture is. The process of making architecture becomes equally important with the produced artifacts.

Then, “urgent pedagogies” are about emancipating active citizens instead of disciplinary professionals. Emancipated citizens who take care of “socially skilled” people. Emancipated citizens, as “socially skilled” people.

Then, “urgent pedagogies” develop relations across siloed disciplines, offering means to produce situated knowledge through practice.

Then, “urgent pedagogies” create a shared language across material cultural practices. They facilitate the creative confrontation of multiple and divergent sources of knowledge. They generate a complex system of synergies between different sources of knowledge production and learning environments.

Then, “urgent pedagogies” are about supporting agonistic practices for urban commons. Emancipated citizens would develop high negotiation skills. They translate how the political is spatially manifested into the city. They develop practices to reimagine a shared future for the city as Dana Cuff and her collaborators urge us to do [21].

The “Encouraging Urbanity Game Series 10- E.U. 10” is a Companion for Cyprus counter-militarization, (2019) [22]. In an elective seminar, fourth- and fifth-year students of architecture together with graduate ones have formed three teams and they have designed three board games. They have profited from the knowledge produced by the aforementioned projects as well as from theories and empirical knowledge regarding spatial practices, including critical play.

The designed games are alterations of existing board games such as Catan and Monopoly where the students replace their extractive capitalistic character with an architecture of sharing.

What if “urgent pedagogies” address the challenges of living in conflict zones, where institutions sustain hostile environments, and division? Cities dominated by conflicts see their urban elements, spaces, and social practices instrumentalized by the conflict itself according to Wendy Pullan.[23]

Then, “urgent pedagogies” is about processes of emancipation of citizens immersed in conflict. It is about learning how to counter institutional presets. Learning how to operate in institutional voids. Finding out how to profit from the existence of such voids rather than freeze due to the absence of institutional support.

Then, “urgent pedagogies” is about creating new relations between the hidden and formal curricula in educational programs of architecture as well as in other fields of material cultural practice. The formal curriculum focuses on the designerly knowledge the students should have acquired by the end of the studio’s semester. The hidden curriculum refers to the ideology of the designerly knowledge and of the social practices that structure the experience of students and tutors, as well as the position they occupy. [24].

Then, “urgent pedagogies” decolonize our urban imaginaries.

“Alice in Meridianland…or the countermilitarization action”, (2019) [25] is part of the Buffer Fringe Performance Festival, Nicosia, Cyprus. The critical spatial practice comments on Cyprus’ actual militarization status by offering alternative urban imaginaries for the urban commons of an island without armies. It has taken place along a loop of streets and public spaces both in the north and the south parts of divided Nicosia.

“Alice in Meridianland” is a camouflage tactic to conceal its anti-militaristic nature while crossing the guarded checkpoints into the city’s north part.

Two tricycles, pulling 3-meter long banners, have followed the loop in opposite directions, three times. They met at designated areas and formed instant spaces of playful interaction. On the banners, the passers-by can see the urban design projects of the students. A spinning wheel is supported on one of the two banners facing each other. It is Alice’s spinning wheel with numbers from two to ten. It is a sort of dice to help the players move along the path of a ladders & snakes game printed on the same banner, on top of a site plan of a military infrastructure.

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

Stratis, S. A counter-project about land regeneration and land use in Larnaca, Cyprus; or, an everyday little utopia; Urban Transcripts Journal, (2020b), Vol 3, No3.

2.

Barad, K. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2007: 72.

3.

Haraway, D. cited by Lykke, N. Anticipating Feminist Futures While Playing with Materialities in Schalk, M., Kristiansson, T., Mazé, R. (eds) Feminist Futures of Spatial Practice. AADR, (2017): 30.

4.

Geerts, E., van der Tuin, I. Diffraction & Reading Diffractively, (2016).

5.

Geertz and van der Tuin 2016, Lykke 2017: 27-32.

6.

Björkdahl A. & Strömbom L. (eds.) Divided Cities: Governing Diversity. Lund Sweden: Nordic Academic Press, 2015:20.

7.

Geertz and van der Tuin, 2016.

8.

Agamben G. Homo Sacer: Sovereignty, Power and Bare Life. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995:175.

9.

Easterling, K. Enduring Innocence, global architecture and its political masquerades. Cambridge Massachusetts, London: MIT Press, 2005: 3.

10.

Easterling 2005: 3.

11.

Stratis, S. Critical Urban Practices for Conflict Transformation, in Pilav, A., Schoonderbeek, M., Sohn, H., Stanicic, A.(eds), 2020. Mediating the Spatiality of Conflicts: International Conference Proceedings, Deflt: BK Books, (2020a): 178-189.

12.

Sassen, S. Beyond Differences of Race, Religion, Class: Making Urban Subjects, in Mostafavi, M. (ed), Ethics of the Urban: The City and the Spaces of the Political, Zurich, Switzerland: Lars Muller Publishers, (2017): 36, 41.

13.

Curator: Peter Cook. Project team: AA&U: S. Stratis, Associates/Advisors: R. Urbano, architect, M. Loizidou, visual artist. Assistants: A. Angelidou, D. Papalouka.

14.

Project team: LUCY (Laboratory of Urbanism, University of Cyprus).

15.

Sennett, R. “Edges: Self and the City.” in Mostafavi M. (ed)“Ethics of the Urban: The City and the Spaces of the Political.” Zurich Switzerland: Lars Muller Publishers: (2017): 264.

16.

Stratis, S., Architecture as Urban Practice in Contested Spaces. in Stratis. S. (ed) Guide to Common Urban Imaginaries in Contested Spaces. Berlin: Jovis, (2016a):, 13-45.

17.

Stavrides, S. Common Space. The City as Commons. London: Zed Books, 2016: 56.

18.

Stavrides 2016 : 56, 70.

19.

Tutors: S. Stratis, Collaborator: P. Tan, Support: LUCY.

20.

Stratis S. Atlas of Designerly Knowledge: Urban Commoning through the Critical Pedagogical Project, in Stratis. S. (ed) Guide to Common Urban Imaginaries in Contested Spaces. Berlin, Jovis, (2016b): 234-254.

21.

Cuff, D. Loukaitou-Sideris A., Presner, T, Zubiaurre M, Jae-an Crisman, J. Urban Humanities: New Practices for Reimagining the city. Cambridge Massachusetts, London: MIT Press, 2020.

22.

“Habitants of Meridianland” (V. Motsiou, P. Christou), “Act of Anti-militarization”, (A. Leontiou, A. Michael, Z. Papaeconomou), “Peace on Common Lands”, (P. Kavvalou, M. Lagoude, K. Miltiadous).

23.

Pullan, W., Conflict’s Tools. Borders, Boundaries and Mobility in Jerusalem’s Spatial Structures. in Journal Mobilities 8:1, (2013):125-147.

24.

Crysler, G. Critical Pedagogy and Architectural Education. in Journal of Architectural Education, Vol. 48, No. 4 (May, 1995): 210.

25.

AA&U, LUCY.

is a Ph.D. architect, urbanist, and activist for the urban commons, Associate Professor, at the Department of Architecture, University of Cyprus. His research focuses on the political agencies of architecture and urban design. He studies the strategic value of urban design, as well as the social dimensions of architecture plus the ways they both transform into critical urban practices. Socrates oscillates between reflective practice and practice-based research, thanks to entanglements between teaching, practicing, curating, and writing. He enriches his research by operating in a highly contested territory, such as the Cypriot one, plus by having an active contribution to the becoming of young European urban design practices through his scientific position in EUROPAN Europe. He’s one of the main founders of the critical urban practice agency AA & U, Cyprus. Soctates’ curatorial and activist work involves the Cyprus participation in the 15th Venice Biennale of Architecture, as well as the “Hands-on Famagusta” project and he was the editor of the book “Guide to Common Urban Imaginaries in Contested Spaces”, jovis. 2016.