Alternative pedagogies and social engagement

Ou Ning

CATEGORY

“In the past two decades, I paid a lot of attention to the empowerment of the ordinary people and the activation of their creative potential on self-organization during the radical changes in the urbanization and gentrification process.”

The term “urgency” came up in 2003 when Hou Hanru invited me to participate in the “Zone of Urgency” section in the Venice Biennale. Then “urgency” became a key word in my projects.

In 2003 I made a documentary about the urban village Sanyuanli in Guangzhou. Two years later I made another documentary film about Meishi Street in the slum Dashilar in Beijing. These two projects focused on the urgent situation of China’s urbanization. It was urgent because there were huge conflicts in the radical urbanization process. I thought of it as a redistribution of social resources. It’s really similar to a revolution. A revolution is exactly about redistribution of social resources. The Chinese urbanization was a radical revolution that redistributed lands, properties and educational resources, as well as the livelihoods of ordinary people.

The young lion dancers in Sanyuanli Village, Guangzhou, 2003. One of the stills from the documentary San Yuan Li by Ou Ning, Cao Fei and members of U-thèque Organization, 2003.

In Guangzhou and Beijing’s urbanization processes, there were many demolition projects. The governments conveyed the lands to developers, but the compensation was too little for people who used to live there. People would have to protest to ask for more justice and compensation. The protests would put China into a dangerous political situation. Same thing went for the rural areas — when the governments grabbed lands from the farmers and used this for development, they also gave very little compensation. Farmers had to defend their rights. This was the reason why so many weiquan events were produced. The radical urbanization process was putting China in what I consider a very urgent political situation.

Before the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the local government decided to widen the Meishi Street in front of the Tiananmen Square to facilitate traffic. The government had to demolish the houses around the street. I met a guy named Zhang Jingli. He protested at that time to ask for more compensation for his house. His way of protest was creative and full of humor. I decided to give him a camera. He had never used digital cameras before but I taught him the basics on how to use the camera. It was not like an education, but rather sharing knowledge or skills. He shot footage daily. Sometimes he even became a narrator, shooting and talking at the same time. He was a “citizen journalist”. This project became about how we could evoke the protests in ordinary people, and how we could help them.

Mr. Zhang Jinli stood in front of his demolished restaurant with the digital camera in hand, Beijing, 2005. One of the stills from the documentary Meishi Street by Ou Ning and Cao Fei, 2005.

Mr. Zhang often hung the protesting banners outside his house. The police would always come to tear down the banners but when Mr. Zhang carried the camera in his hand and put the focus back on them, they stayed still and dared not tear down the banners. The camera “empowered” Mr. Zhang’s protest. This was one example that I could connect my practice to “urgent pedagogy.” I don’t like the term “empower.” I prefer to “activate” the power within people. It’s different from giving power from the top-down to the people.

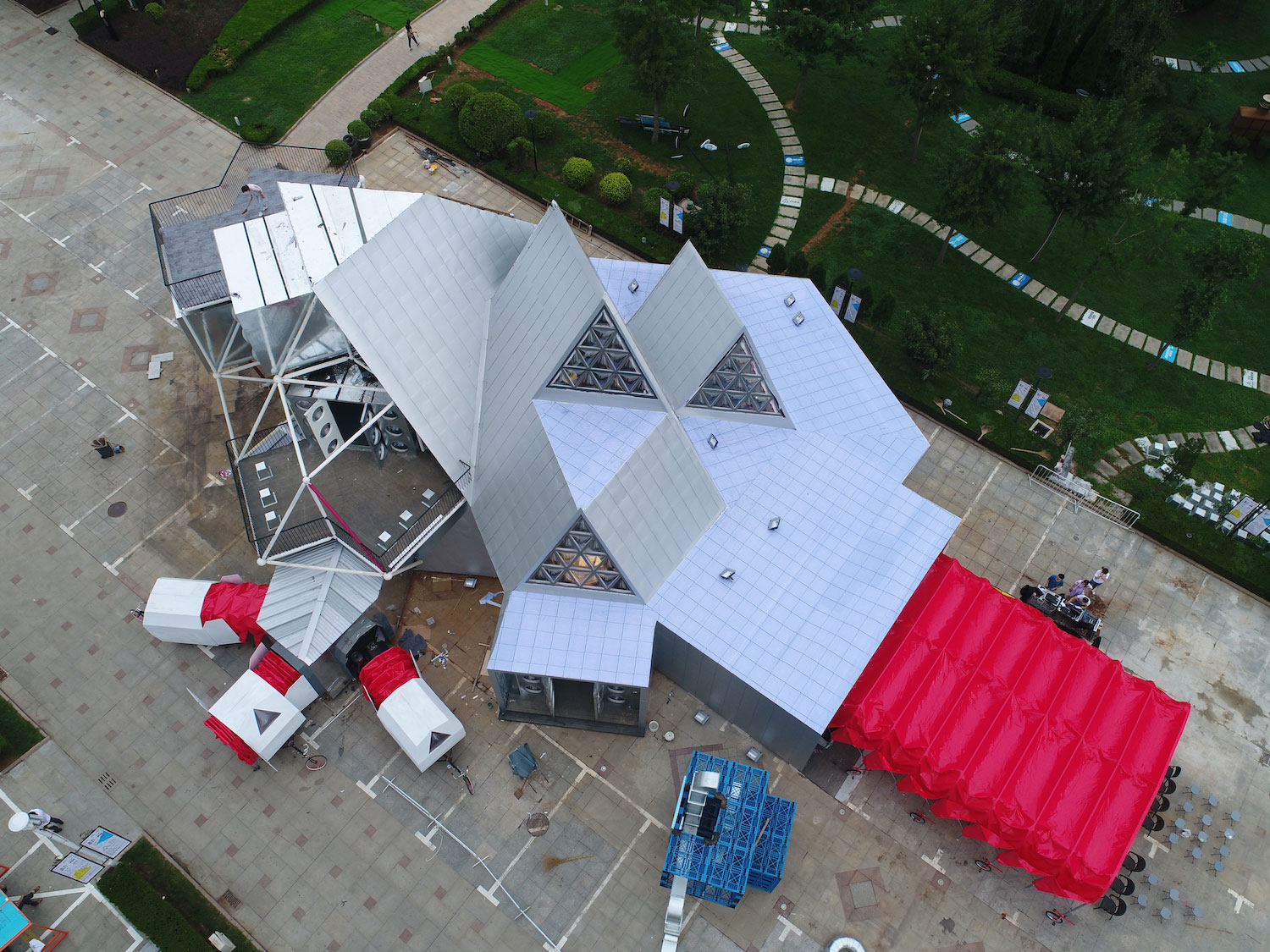

Whether it was the Sanyuanli Project, Dashilar Project, Bishan Project or the recent Kwan-Yen Project in Yantai, we still had to confront the same urgent situations. After the 2008 Beijing Olympics and 2010 Shanghai World Expo, the urbanization process in China expanded to the provincial capitals, second and third-tier cities, as well as the wider rural area. The problems emerging in the rural areas were more urgent and radical. The Bishan Project was a response to the urgent situations such as the bankruptcy of agriculture, the atomization of farmers and the depopulation of the rural society.

It was not my decision to make this shift. I just followed the facts. China’s urbanization movement had two phases after the New Millennium — the first decade from 2000 to 2010 was focused on big cities like Shanghai and Beijing. At this time, big events like the Olympics and World Expo were the main driving force for urbanization and the slum phenomenon was quite rampant. A huge number of migrant workers poured into these big cities in search of a job. They could not afford to live in the cities, so urban villages and slums became a typical result of the urbanization process between 2000 and 2010.

2010 to 2020 is the second phase. After 2010, the slums disappeared. The urban villages were no longer a central issue for the second phase. Because of highways and high-speed railway development in different provinces, mobility was improved. This became a main driving force in the provincial capitals/cities. Cities like Chengdu, Suzhou, Wuhan, Hangzhou, Zhengzhou, Nanjing, Changsha, Yantai, developed very fast.

The main conflict in the second decade was around how to balance the different regional developments. The central government focused on the so-called chengzhenhua (townization) policy. In the second decade, the central government used the term “townization” rather than “urbanization”. This means to develop towns around rural areas and moving rural populations into these towns, and was closely connected with the “Rural Revitalization.” This process gave rise to some urgent situations. The local governments built gated communities and modern apartments and asked villagers to move into these apartments. However, the governments did not provide any jobs for the rural populations. So even though these villagers were living in modern apartments, they did not have money to pay for utilities. They could not cover any cost for living in a gated community. They didn’t feel happy living in these apartments so they decided to move back to their original villages.

The problem then became how to satisfy the villagers and how to balance the developments of urban and rural areas. The problems of rural development are always a serious topic for the central government. If they harm the interests of the farmers, the farmers would protest. The farmers’ protests are different from the urbanites’. They always protest together. In the cities people often protest individually, just like Mr. Zhang Jingli. The urbanites don’t group together. But the farmers in the countryside can group together because their lands are collectively owned. Their interests are connected with one another. A very urgent situation would arise when a local government faces group protests from farmers.

I have seen this potential danger, and I have also seen that many problems in cities are actually related to the countryside. The urban-rural relationship is not equal. Cities often plunder rural areas. Farmers provide food, labor and land for urban development, but they could not share the achievements of the cities. Therefore, I think it is very important to take care of farmers’ sense of wellbeing. The solution of rural problems is the foundation of China’s modernization. So I decided to shift my focus from cities to the countryside.

The reason I started the Bishan Project was because when I lived in Beijing, I came to understand the serious problems of big cities. I lived in the CBD (Central Business District) in Beijing, the traffic was always busy, air pollution was terrible, and the population density was high. Job opportunities became very slim as the job market was competitive. Living in the big city wasn’t a happy life.

I originally came from a rural area in Zhanjiang, Guangdong. I grew up in villages. My family was very poor economically and culturally. When I was younger, I went to university and found a job in the city. When I think about my hometown, I’m reminded of people like my family and my villagers who were forgotten by the country. When I went to Dashilar, the slum of Beijing, to make the documentary and meet farmers-turned-migrant-workers who were from different provinces, I was reminded of my family and my villagers. These farmers contributed a lot to the country. In the 1960s, when the People’s Commune Movement concentrated agricultural products to export to the USSR in exchange for industrial resources, the farmers contributed with their agricultural products. At the end of the 1970s China began to open up and reform the economy. The land of the farmers in Southern China was also concentrated by the government with the aim to open factories. The labor needed for the factories all came from the countryside from Guangdong, Hunan and Sichuan provinces. So the farmers contributed labor for the Open Up and Reform years, they helped develop Shenzhen, Guangzhou and other big cities.

So the Farmers contributed a lot, but the benefits they can share are little. When they realized this fact, they began to understand what their “rights” meant. That is why the central government decided to kick off the “Building New Socialist Countryside” movement, to satisfy the farmers, to keep them calm and keep protests at bay by creating a “peaceful and harmonious” society. Harmony means keeping people in the countryside satisfied so that they won’t protest.

The urban-rural conflict was very serious. For example, when the farmers go to the city to find jobs, the urban people need them but don’t like them. Also because of the hukou (household registry) system, rural people could not share the same resources as urban people. The conflict between these two classes was very serious. So something needed to be done to keep the society balanced. The government needed to do something, the unofficial people like myself also wanted to do something. Because I came from the countryside and I understood the situation. I wanted to make a change by starting the Bishan project.

My activities in Bishan Village had a very close connection with “urgent pedagogies” and “alternative pedagogies.” When the local government intended to concentrate the farming lands of the villagers to sell to an industrial agriculture company, I organized a meeting with the villagers in my home and working base Buffalo Institute to discuss what is the best future for the village. I argued that the villagers should keep their lands to produce food by themselves. Although the discussion could not stop the land sales, it engaged the villagers to start thinking about their future alternatively. Later I helped set up the Bishan Bookstore in 2014 and founded the School of Tillers by myself in 2015. We created public spaces in the village. The Bishan Bookstore and the School of Tillers became like community centers. Many events were held in these spaces and the villagers liked visiting them. All these events and activities had educational components. We organized exhibitions, screenings, lectures and workshops. All villagers were invited to participate. Sometimes they were invited to perform by themselves. Everything we did was connected to how we could share knowledge with each other. The villagers learned art and culture from the outsiders, the outsiders learned agricultural and local knowledge from the villagers. It was like a kind of “mutual learning” experiment.

I don’t like to use the term “education” in my rural practices. “Education” means someone from the top teaches those in the bottom. But when you want to do something in rural China, what’s commonly known as “education” is still a main practice that holds the most possibilities.

I regard the Bishan Bookstore as successful because every day the villagers, especially the elderlies would come to the bookstore. They often stayed there for three to four hours. They got a copy of a book and started reading. Young kids also came, but they mainly came for the internet. During the Qingming festival, a lot of villagers who worked in Shanghai and Nanjing came back to the village. They were very proud of the Bishan Bookstore. They introduced the bookstore to their friends from other regions. There was a local couple who asked to use the Bookstore to hold their wedding ceremony. The bride was the daughter of an older teacher in Bishan, she studied in the US and came back. She and her father suggested holding this wedding in the Bishan Bookstore. That was a good example of the responses that the villagers had toward the Bishan Bookstore. They really thought the Bookstore was a “place” that belonged to them.

At the School of Tillers, we helped the villagers to sell their agricultural products and directly sent the income to the villagers. At the same time, every evening after dinner they came to the School of Tillers, because we had daily events for them. The screening programs were not curated by us, they were decided by the villagers. For example, when they wanted to see the TV program Dream of the Red Chamber, they would tell us, and our staff would download the TV series online and screen it for them. The programs were catered to the villagers’ requests, so they came every night as a daily routine for chatting, gathering, screening and sometimes for dancing. For me, this was also a success for the School of Tillers.

I understood that all the villagers were looking for better income. However, I still think culture is very important. Culture is very necessary for the villagers. The reason I started the Bishan Project was because villagers still think that the city life is better than the countryside. New things are better than old things. The main problem is that they don’t think their lives are valuable. They are not confident enough with the value of their rural life. That is why whenever there is any opportunity, they will definitely move to the city. Young people especially like new things and money. This is reasonable, but if everybody is always looking for new things, money and economic growth, I believe the society will not be harmonious. This is why I think cultural nourishment and alternative pedagogy are important.

The Bishan villagers came to the School of Tiller for artist Liu Chuanhong’s film screening. Photo by Zhu Rui, 2015.

When the villagers don’t like their old house, they will build a new house if they have the money. Our “pedagogy” was embedded in how we fix and regenerate the old houses, to make the empty old houses comfortable in relation to the contemporary standard. So when the villagers visited us, they saw the regenerated old houses, they understood the value of their old houses. That is what I call “silent education.” We just did something that became an example. That is the power of culture, to let people understand that old things are valuable. Now the price of old houses in Bishan has risen several times more than in the past. The buyers from cities paid for the old houses, raising the villagers’ income. The economic relationship between outsiders and villagers are not conflicted but mutually beneficial.

However, I hope that this kind of transaction can be controlled within an appropriate range. For example, villagers would still live in the village after selling the houses they no longer live in, and outsiders can move in and live for a long time after buying the houses in the village, not only for vacation. At the same time, a balanced proportion between local and foreign population should be kept, so as not to cause the phenomenon of total gentrification.

Why are bookstores getting so popular recently in China? This is a very interesting question. In rural China, villagers don’t like art. They think art is useless. That is the reason that organizing art exhibitions, especially contemporary art exhibitions in the countryside, makes no sense to them. But the villagers always believe that reading can change their fortune and life. That is why they always pay any price to send their children to school for “reading.” Schooling usually means reading in China. People in cities and the countryside all believe reading books can change their lives. So they like bookstores and libraries more than museums and art galleries. I believe this is a very typical aspect of Chinese culture. This is the reason why I always start from a bookstore or library in my socially engaged projects. Bishan Bookstore is the first rural bookstore in China. The School of Tiller also had a study space. With the Kwan-Yen Project in Yantai, I also started from a neighborhood library.

From an architecture and spatial function point of view, Bishan bookstore was regenerated from an ancestral hall Qitai Tang that was more than 200 years old. The whole building was typical Hui-style vernacular architecture. It had a tianjing (sky well), which is a very typical feature that connected the architecture to the sky. An ancestral hall was traditionally a public space for the Chinese rural societies. In the past, when villagers needed to make a decision, they had meetings and conferences in ancestral halls. They always had public discussions in those spaces. It was also a space for people to express their respect to their ancestors. The ancestral hall is akin to a church in the Western society.

When I invited Qian Xiaohua, the owner of the Librairie Avant-Garde in Nanjing, to open a rural branch in Bishan Village, we found this old empty ancestral hall Qitai Tang. The property was collectively owned by the villagers. I persuaded the villagers to let us use it for free for 50 years. The local government helped make this agreement. The deal was interesting, the villagers didn’t sell the building to us, we didn’t rate it or pay any money, rather, we used it as a bookstore and gave it a new function, then it became a common space. This practice resonated with a movement in Rome, Italy in 2011 – 2012. The Teatro Valle is an 18th Century theatre that was left empty because the government didn’t have enough budget to run it due to the financial crisis, then a group of young intellectuals in their 30s and 40s (Trenta-Quaranta) occupied the theatre. Normally the property ownership belonged to the government. But these intellectuals occupied it to organize a large number of events to activate the empty space as a new common space. They put the property ownership issue aside. What we did in Bishan was similar. We didn’t talk about ownership, we just made things happen together.

This project was a new initiative in China and it was successful. Villagers can share the success of the bookstore because it brought many visitors to the village. The Bishan Bookstore brought several rural branches of Librairie Avant-Garde supported by local governments in other provinces.

Coming back to the physical space of Bishan Bookstore, it had a sky well, so rain could come directly through. It was a challenge for us to protect the books. But the rain made poetic moments for the people. When the rain falls from the sky well, you can pick up a book and listen to the sound of the rain. The gray tier and white walls from the traditional Hui-style architecture are very beautiful. The architect we invited didn’t make any change to the facade or inside of the building, he just produced some bookshelves inside the hall. When the books filled the shelves it made the interior very beautiful.

The School of Tillers also started from an old ancestral hall. It was very important for me to design the function of the building. I set up a gallery, a screening hall, a small library, a café and a zakka. It had many functions. The most important were the public spaces, they became strong attractions for the villagers. We only renewed the building, we didn’t add any new structures to the space and just kept it as it was before, because the Hui-style vernacular architecture is very strong, so strong that it would make a contemporary architect feel powerless. In Particular, the Hui-style house has a secret to design the common space at home. It has small bedrooms, but it has four big halls. This means the family only stays in their bedroom when they sleep, normally they will go to join the family life in the different halls and common spaces. This is a successful way to run a common space. Just like that you have a square in the city and you want to bring people there, you need to mix up residences, restaurants, bars, cafés, shops and spaces with different functions around the square, if you design the residence as a small space, people would like to go out to socialize instead of inviting friends to their small homes. That is the way that a square can become a successful public space.

When I visited the Earthsong ECO-Neighbourhood in Oakland, New Zealand, I found that they also used this same method. When they planned their community, they kept the bedrooms for each household very small. But the community center and public canteen are very big. The community members go to the canteen for meals and socialize in the community center every day. I think we have a lot to learn from the Hui-style vernacular architecture.

As for Suochengli Neighborhood Library, I invited Dong Gong from Vector Architects to renovate a typical Northern China courtyard into a small library for the people of Suochengli. He just added a weathering steel cloister system to connect the reading room, gallery and café, complementing the historic brick, stone, and tile, then produced a new spatial quality. It became a convenient station for knowledge sharing in the neighborhood with weekly educational events organized by the local people.

In the past two decades, I paid a lot of attention to the empowerment of the ordinary people and the activation of their creative potential on self-organization during the radical changes in the urbanization and gentrification process. I was also interested in community-based practices and how to make “places” where people can develop relations, identity, history, local knowledge (mῆτις, metis) and topophilia, places where people can be friendly to the environment and find sustainable ways to survive.

To build a better community, regardless whether in urban or rural areas, means not only the planning and building of a physical space, but also the construction of social structure. I’m interested in architectural and environmental design, but also interested in the founding of political principles: how people search for consensus, how they make decisions on the public issue, how they distribute the resources, how they organize their society.

When working on the Bishan Project, I started my research on the rural reconstruction projects, countryside art projects, hippie communes, intentional communities, ECO villages and utopian practices in different countries and regions. I visited the historical sites where James Yen, Liang Shuming and Tao Xingzhi started their experiments in Republican Era and interviewed many rural reconstructionists and activists in Greater China area (2009); the Land Project found by Rirkrit Tiravanija and Kamin Lerdchaiprasert in Chiang Mai, Thailand (2010); Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial founded by Kitagawa Fram in Japan (2012); Riverside Community, Rainbow Valley Community and Earthsong ECO- Neighborhood in New Zealand (2013); Metelkova Mesto in Ljubljana (2014); Fristaden Christiania in Copenhagen (2014); Paul Glover, the founder of Ithaca Hours in Philadelphia (2014); Tuntable Falls Community and Dharmananda Community in Nimbin, Australia (2015).

When I got an opportunity to teach at GSAPP Columbia for two semesters in 2016/2017, I started to visit the utopian sites from 19th Century America: the Shaker Village, Pleasant Hill, Kentucky; the Oneida Community founded by John Humphrey Noyes in upstate New York; Josiah Warren’s Cincinnati Time Store in Ohio; George Rapp and Robert Owen’s New Harmony in Indiana. From 2017 to 2019, I visited Owen’s New Lanark in Scotland, Kurt Schwitters’ Marz Barn in Lake District, Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirst’s Dartington Hall in Devonshire, Brook Farm in Boston, Saneatsu Mushanokōji and White Birch Group’s Moroyama Village in Japan. Unfortunately, the outbreak of Covid-19 interrupted my planning field trips on the Kibbutz movement in Israel, and Rabindranath Tagore’s Santiniketan as well as Mirra Alfassa’s Auroville in India.

The research was about collecting historical experiences and thinking resources to improve my practices in Bishan. However, with the political condition and limited political space, it was quite difficult to realize the radical ideas in China, for example, the ideas of communal living and collective ownership, and the anarchist idea of “direct action”. When the Bishan Project was banned by Beijing in 2016, I decided to turn the research into a book Utopian Field with my narrative and analytical writings.

Today I think this book would become a helpful reference for people to deal with the post-pandemic condition. The utopias or intentional communities in my research always settle down in the countryside, wilderness or mountains, because they wanted to keep out of mainstream society. Today, when we face a crisis such as the pandemic, or when you lose your job, you cannot afford your city apartment, you might consider moving out to the countryside and share something with your friends. This might become an alternative choice for people – when you can’t support your so-called middle class life in the city. The alternative might be a shared, low cost, environmentally friendly rural life. The pandemic could become an opportunity for people to practice an intentional community, or realize a small utopia in the countryside.

One case study I learned about was Tao Xingzhi. He founded a school in the suburbs of Nanjing in the Republican Era to cope with the urgent situation at that time. When China just started a new republican system from the old empire, it faced many problems. The educational institutions could not provide any help for the people. When China tried to realize the republican political system, it was apparent that many farmers didn’t understand the meaning of democracy. This was the urgent political situation that urged many Chinese intellectuals to move to rural areas to start rural education movements. Tao Xingzhi established a teacher’s school in the Morning Village (xiaozhuang) of Nanjing. He hoped each student who graduated from Morning Village School should become a village teacher and found a new school in at least one village. Then China would have many village schools. In these village schools, just like Morning Village School, all the teachers, students lived together with the villagers, they cooked and farmed together, and tried to protect themselves through military self-trainings in the troubled times caused by the warlords. Each student was also a teacher, and vice versa. A mutual learning model was established. At that time this was a very radical and alternative pedagogical model.

Around the same time there was the mass education movement led by James Yen. Both Tao and Yen creatively practiced the British Bell-Lancaster Method from the early 19th century (also known as “mutual instruction”) in rural literacy education in China. The young peasant students who learned best would become “little teachers” who taught older peasant students. This ripple-like self-education amongst peasants greatly “mined their intellectual mind”. Compared with Paulo Freire’s “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” developed from Brazil’s literacy movement in the 1960s, Tao and Yen’s approach to mass education was more inclined to soften the social conflicts. There was no smell of gunpowder through class struggle in Tao and Yen’s practices.

There were some anarchist practices in China during the same period. Most of them wanted to set up a farm, because they believed life was education. The farms were not like academies where there were hierarchies. One had to do everything by oneself. These examples are very important inspirations for the contemporary practices by the new generation of Chinese anarchists.

Today all the schools in China are controlled by the government. The so-called education is really just brainwashing. There are also people who found schools in the countryside, using alternative pedagogy to teach children. But still they are not radical enough compared to what Mr. Tao Xingzhi did. The contemporary condition is very different from the Republican Era, because the party controls the society too tightly. The ideal pedagogy cannot be realized in China’s reality.

The Bishan Project was a non-governmental and not-for-profit project. It was a big challenge for us to maintain it, especially as we were just individuals rather than an organization. As a so-called “anarchist,” I don’t believe in any organization. So, funding became a big problem for the project.

I had to do some fundraising from friends, or work for some companies or institutions in exchange for their support. I was the chief editor of a literary magazine Chutzpah! published by Modern Media Group, I also did curatorial jobs for them, I invested most of my incomes in the Bishan Project. It cost a lot of money for me to regenerate the building of the School of Tillers. The project did not bring any income to me but increased my spending and it seemed financially unsustainable. When I organized exhibitions in Bishan, it became another difficult thing. We needed to talk to galleries if artists were represented by them, we needed a budget to make the installations.

Ou Ning, Utopia in Practice: Bishan Project and Rural Reconstruction (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020)

When we organized the first Bishan Harvestival in 2011, it was totally self-funded. It became better when the local government commissioned us to curate the Yixian International Photo Festival in 2012, we were paid and then we could organize the second Bishan Harvetival with the payment. But the photo festival was canceled by Beijing before the opening because it coincided with the 18th National Party Congress. After this year, everything we did in Bishan had no support from the governments.

In addition to fundraising, I had to maintain good relationships with the villagers, the governments, artists and the press. It was a tough job for me. But in the six years when I lived in Bishan with my family, I really enjoyed my daily life there. Every time when I came back from the outside world, I could see my home at the foot of the mountains under the beautiful clouds from afar. We lived in an old Hui-style house, welcoming guests and seeing them off every single day. We often participated in the villagers’ festive banquets, attended their Huangmei Opera performances, danced with them in the square, swam together in the Yuanyang Valley in the summer, and chatted in front of a fire in the winter. We also sat reading by the brazier, and went to the swap meets in the county town every new year’s day to purchase local specialties. The beauty of the surrounding unknown villages and the natural scenery was never tiring. It was an unforgettable memory, which I wrote down in my newly published book Utopia in Practice: Bishan Project and Rural Reconstruction (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

Ou Ning in Bishan. Photo by Zhu Rui, 2012.

This text is based on an interview by Michelle Song for Urgent Pedagogies.

is an artist, film maker, curator, writer, publisher and activist based in Jingzhou, China. He is the director of the documentaries San Yuan Li (2003) and Meishi Street (2006); chief curator of the Shenzhen & Hong Kong Bi-city Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (2009); jury member of 8th Benesse Prize at 53rd Venice Biennale (2009); member of the Asian Art Council at the Guggenheim Museum (2011); founding chief editor of the literary journal Chutzpah!(2010-2014); founder of the Bishan Project (2011-2016); a visiting professor at Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation (2016-2017); and a senior research fellow of the Center for Arts, Design, and Social Research in Boston (2019-2021). His collected writings Utopia in Practice: Bishan Project and Rural Reconstruction is just published by Palgrave Macmillan (2020).