A pedagogy for decolonizing life

Cibele Lucena and Joana Zatz Mussi

CATEGORY

“The self-invention of a space, a time and a political body – individual and collective – had to do with the invention of the means by which we started to be able to talk about certain things, always asking ourselves what we are doing, how, why, with whom and where. None of this involves easy answers, precisely because it results from an existential proposal in which everything is yet to be created.”

Grupo Contrafilé (Contrafilé Group) was formed in the early 2000s in São Paulo, Brazil. At the time, we were a group of students and needed to create a collective space for action and thinking, different from what was offered to us by the logic of the labor market, structured by the idea of individual careers. We envisioned the creation of a collaborative, shared space, a place of existence.

As students, we always heard the questions: what will you do with your life? Where do you intend to work? It was even more difficult for outsiders to glimpse the density and permanence of this collective experience, and to believe that it was not just a set of occasional meetings between friends, to make “protests”. In this sense, the group as a living space was a true invention. It started with the urgency of being together to act on certain social situations that were present, and it developed as an awareness of how much it could transform both ourselves and reality. In this process, we created our own ways of doing and saying spaces and times that could only exist through a collective body.

One of the first situations we dealt with was the perception, physically, of an emptying of public space. We were still very close to the end of the civil-military dictatorship that took over the country from 1964 to 1985. When we started to deal more deeply with this emptiness, we met the thinker Suely Rolnik[1]. Rolnik taught us to always be attentive to the simultaneous relationship between micro and macro politics. And it was with this learning that we realized that our fear of going out into the social space, of confronting the public space, was directly linked to the fact that we are “children of the dictatorship”.

This fear was – and still is – very present in urban territories, embodied in the figure of the Brazilian “Military Police”. With one of the highest killing rates in the world, the Brazilian Military Police targets mainly young and black people who live in the peripheries of large cities. Taking this into account, the first exercises we did as a group were very much related to an awareness of how such a context is established in our own bodies, in the form of a fear of manifesting/expressing oneself.

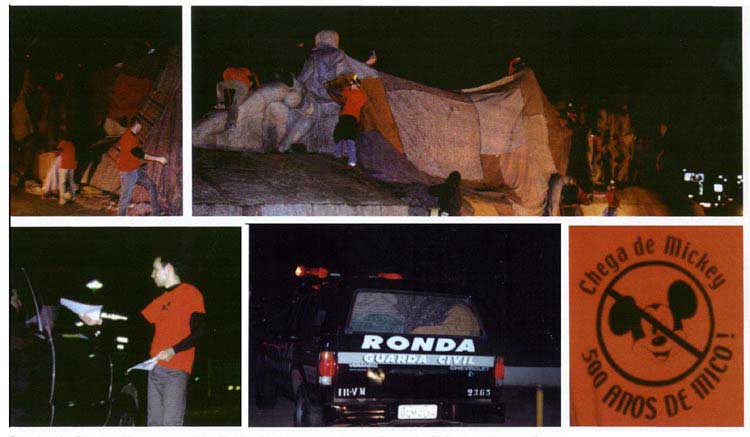

Our first public action took place when we were part of the MICO group[2], in April 2000, at the exhibition Brasil + 500 – Mostra do Redescobrimento (Brazil + 500 – Exhibition of the Re-Discovery). The latter celebrated the 500th anniversary of Brazil based on a false subversion of the idea of “discovery”[3]. The exhibition´s title addressed itself as an act of “rediscovery”. In order to do that though, it would be imperative to directly mention and take a stand against the continued genocide and slavery of indigenous and African peoples in the Americas. The action started during the assembly of the exhibition, when young people who were preparing to work as educators noticed several “inconsistencies” in the event.

Blankets for homeless people, sewn together, forming a large blanket. Artist Roni Hirsch (MICO group). The work covered the “Monumento às Bandeiras” (Monument to the Flags), close to the pavilion of the Bienal de São Paulo. The Bandeirantes were a kind of colonial militia (16th C) that explored the backlands of the country in search of silver and other precious metals, indigenous people to enslave and Quilombos to exterminate. Photo courtesy of MICO, São Paulo, 2000.

These young educators who were linked to the Fundação Bienal – the largest art institution in the country and promoter of the São Paulo Biennial – resigned. Together with friends (forming a group of university students from various disciplines – geography, social sciences, visual arts, architecture, journalism), they problematized their ongoing discussions by intervening in the public space from innumerable strategies: written manifesto, performance and urban intervention. In an exhibition with such visibility, they saw an opportunity to highlight the lack of in-depth and critical review of Brazilian social memory.

Shortly after we started taking action, we met the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo [4], the HIJOS[5] and the GAC (Grupo de Arte Callejero)[6], Argentinian human rights and art groups that directly confront the repressive state and its consequences. Argentina lived under a dictatorship from 1976 to 1983, which left a balance of 30,000 missing people and 500 kidnapped babies (children of political prisoners who were born in prison and were appropriated by the military, growing up without knowing their true origin). Due to the Latin American historical proximity, these groups of Argentine artists and activists have become, for us, important references of a culture that invents new ways to “say what needs to be said”. We got to know them more deeply in 2004, during an informal meeting with the theoretician, artist and activist Brian Holmes in São Paulo. Holmes presented us with various works by groups and movements from other parts of the world, in an attempt to make the São Paulo collectives understand that they were inserted in a much broader context, and that there was a whole network with which they could start sharing.

The solutions found by the GAC in the “escraches”[7] and gravestones scattered throughout Buenos Aires – giving visibility to those murdered on December 20, 2001 during the popular rebellion that occurred this year – drew everyone’s attention. Subverting official codes by introducing messages that bring up traumas, the city was marked from the stand-point of State terrorism. It therefore displaced the city from an “ideological” place, and an often anguished criticism in which the victim individualizes themself and suffers in silence. After a long time, our experience in relation to the military dictatorship in Brazil was finding an echo. We saw here “a power that strengthened us”, that made us want to act; a way of talking about memory that, in itself, already announced the emergence of something new.

Deeply touched by these actions, we decided, together with other collectives in São Paulo, to write and raise funds to promote a face-to-face meeting between us and the GAC. The “Zona de Ação” (Zone of Action) project was the result of this onslaught. Contrafilé, Frente 3 de Fevereiro, Cobaia, Bijari and Suely Rolnik, from São Paulo, invited GAC and Brian Holmes to participate in a process of artistic and political production that would last a few months. The project consisted of the interaction between each participating group, and an area of the city of São Paulo (north, south, east, west and center). Based on this interaction, each group would give a response that in some way would create a significant symbolic inscription in the public space. With the attentive support of Holmes and Suely Rolnik – as well as the other groups, including the GAC who spent fifteen days in São Paulo with all its members and participated actively, bringing many contributions – the collectives involved were able, little by little, to understand what they were feeling from the process, giving shape to those sensations. Contrafilé’s “Program for the de-turnstilisation of Life Itself” is clearly the result of all these interactions. (Translation note: In the Portuguese original text, the wording makes direct mention to the “turnstile”, catraca in Portuguese; therefore the term “descatracalização” or de-turnstilisation, indicates the undoing of our “turnstile-society”). In it, the “turnstile became a symbol” that represented the difficulty that we feel in our country and city to cross the different borders and walls, visible and invisible, that produce and reproduce segregation on a daily basis. Discussing the concept of overidentification[8] while in conversation with the GAC, the Contrafilé Group decided to propose a “public program for the de-turnstilisation of life itself”. This started with a “Monument to the Invisible Turnstile”, which had a series of consequences[9]. The GAC was decisive at that time, since they’d been acting/ engaging from the stand-point of the displacement of discourses and official symbols, as a direct representation in the urban context.

GAC work: Direct Action. Tribute to those Murdered by the Police Repression in the Popular Rebellion of December 20, 2001. In this work, the real places in which people were murdered by the police in the city of Buenos Aires during the popular rebellion (the Argentine “pancho”), were marked with a symbolic headstone. A death ritual was performed with the presence of family members and friends of those killed. In conversations with the GAC, we understood that this was one of the ways they used to subvert the idea of the “grand and vertical monument” as well. They called this “horizontal monument”, a terminology and strategy later adopted by groups in São Paulo. Photo by GAC collection.

Monument to the Invisible Turnstile. Largo do Arouche, São Paulo, June 2004. Photo by Collection Contrafilé Group.

The self-invention of a space, a time and a political body – individual and collective – had to do with the invention of the means by which we started to be able to talk about certain things, always asking ourselves what we are doing, how, why, with whom and where. None of this involves easy answers, precisely because it results from an existential proposal in which everything is yet to be created. Bolivian thinker and artist Maria Galindo helped us with her category of “forbidden relationships”, to confront this type of question[10] based on our place of gender, class and race (mostly white university-middle-class cis women).

In the book Ninguna Mujer Nace para Puta (No woman is born a whore), Maria Galindo and Sonia Sánchez (2007) use the image of the forbidden relationship as a subversive force to talk about a subjective rupture that activates connections between worlds and the work of translation and counter-translation, from which spaces of understanding become possible: “It is a forbidden place and for that reason it can be very subversive, because it would break with the deepest form of control and power of one being over another”. The authors still say that the subversive force does not come simply from the enunciation of differences. It comes from the passage to a more elaborate place, in which this type of forbidden alliance is achieved through a “cruze de miradas” (interchange of looks)[11]. Galindo, elaborating in this notion, refers especially to the historically prohibited relations in her country, between women from “different worlds” (indigenous, lesbians and prostitutes), and to the power/potential that arises with the rupture – internal and external – of the prohibition (understanding that the prohibition comes from an unspoken norm and not an explicit norm).

It became increasingly clear to us that it would not be possible to create anything significant without touching these closed, forbidden places reserved for us. Because without that, we simply would not be able to understand the problems that presented themselves. A central part of our engagement and militancy became the creation of strategies to find ways of life that challenged us, in thought and action, to come out of what was expected: quilombolas[12], indigenous people, black movements, deaf communities, student youth, poets and peripheral artists, partners of the LGBTQI+ movement. We made this journey collectively, through groups and movements that were fundamental for us to face, in depth, places of historical and cultural pain.

In 2005, a rebellion in the CASA / SP Foundation (Center for Social and Educational Assistance of Adolescents), a prison for offenders under the age of 18 created in Brazil in 1964, generated a productive malaise, becoming the impetus for a process of investigation-action that never stopped. Those we saw as “just children”, were deemed by many in society – including the media – as “criminal”, “delinquent”, “intern”. However, naming them clearly as the children they were, ended up showing us that the child is not only an age condition, but also something that traverses us all, a becoming and a strength/force. Therefore, if the rebellion sought to manifest this force, the mechanisms that aimed to contain it were proof of how difficult it is to support it.

We then set out to create devices and images that could reveal the power of becoming-children, for children who live between the streets and the prison. We installed swings on overpasses, and established temporary yards in downtown São Paulo. In an autonomous and collaborative way, we built parks with communities, in an attempt to cause disruptions in this cartography of the extermination of children (mainly poor, mostly black and indigenous). An extermination carried out by a system that cannot bear them as an imminent rebellion and the possibility of a radical transformation of the given reality.

In 2014, the A Rebelião das Crianças (The Children´s Rebellion) project was developed in A Árvore-Escola (The Tree-School), which came from the meeting between Contrafilé, the Palestinian group Campus in Camps, and Rede Mocambos[13]. The meeting triggered a question that led to the development of the project and would further expand our reflection on education: here in Brazil, what key force has the power to liberate the continuous process of colonization to which we are subjected? When we realized it, we were all sitting together under the shade of the Baobab tree, inspired by the quilombola matrix. The Baobab tree is an ancestral tree that traverses time and keeps/safeguards memories. Antenna tree, connector of the return to oneself, and that whenever planted, decrees a free territory. Tree-school, teacher of a listening that is necessary in order to go beyond that which is apparent, and recognize the life-sustaining pulse. Incolonable body-tree.

The baobab made us rethink what we socially call “school”, rescuing its original condition – a group of people sitting in the shade of a tree. Students do not know they are students and teachers do not know they are teachers, but everyone learns together. A tree has become, for us, a kind of “minimal element” to form a school, a meeting place for people who share similar urgencies. The tree, with its characteristics and history, is capable of creating a common territory where ideas and actions can arise.

In this process, we learn that the tree is not a metaphor, nor a symbol of an alternative form of school, the tree simply is: “Tree is not a word, it is a person; school is not a building, it is strength; and everything that pulsates life is school ”.

At the end of 2015, we were traversed by the events of more than two hundred state schools being occupied by high school students. Students who, in protest against a reorganization imposed unilaterally by the state government, demanded necessary changes in the educational system. We recognized in high school students a cut/fissure/tear (Translation note: in the Portuguese original text the word used is rasgo, which literally means “tear”) that allowed us to establish connections with A Rebelião das Crianças and A Árvore-Escola.

Chairs hanging from a school under occupation. Source: The One With No Manners. Available at: O mal-educado https://www.facebook.com/mal.educado.sp/>. Accessed on: May 2017. Photo by Collection Contrafilé Group

Starting from affection, care for the space, relationships and ourselves, we understand that the movement was a Battle of the Living[14], rebellion of the body affected by an authoritarian macropolitical situation: “I am in this classroom and it cannot close down”. The school occupations played something of a joke, created a state of rebellion that coincided with the child-state itself and defied normality by expressing the principle that “it is actually the how in how you teach, that is actually being taught”.

The invitation for Contrafilé to participate in the exhibition Playgrounds 2016 at MASP – the São Paulo Museum of Art, came in due course as a concrete possibility of meeting the group with high school students to create a common work. The exhibition made possible the construction of what we call a “Device Space” inside the museum – an installation composed of different work environments, of different natures, which hosted the meetings with students, educators, artists, researchers and friends.

Device Space, installation of the Contrafilé Group at the Playgrounds 2016 Exhibition, held at the São Paulo Museum of Art. Photo by Julio Cardoso / Collection Contrafilé Group.

The history of Contrafilé Group, has been continuously built on dialogue and in confrontation with the Brazilian context, rooted in colonial and slave-based logic. When we started making the journey to intervene in the city, that is, to put the body physically at risk, we realized that this was an effective way of taking over, as well as deconstructing this history. This risk assumed by the body – which can be attributed to an awareness that makes us question privileges and initiates a process of self-questioning – cannot be dissociated from the desire to decolonize itself.

As soon as we connected with the Rebelião Secundarista (Secondary Rebellion) from 2016, we understood that the rebellion was closely related to a confrontation. Confrontation (by students who descend from indigenous peoples, quilombolas and the diverse miscegenations between these matrices and others present in Brazil, from all over the world) with a whole history of oppression, through the production of another school. A school in which their bodies can exist. A school in which study and research are connected to their realities. A school that helps everyone to truly think about the country and the world in which we live. A school that, as a living body, connects with what pulsates, with what matters, surpassing walls and fences and the very idea of ”inside” and “outside” the school.

As the poet Tatiana Nascimento, who conceived and taught the White Privilege Workshop, in which we participated, said the country is founded on a pedagogy of racism that structures all relations and institutions in Brazil. Therefore, it is not about the lack of a pedagogy, as one can often think, but, on the contrary, the presence of advanced teaching and learning technologies, through which people teach and learn to be racist. These pedagogies guarantee the long duration of the colonial project, which lasts until contemporary times. We are, in many ways, a colony project, established now for over 500 years and that systematically creates and recreates strongholds of privilege and exclusion. For this reason, all the pedagogies we create, which we can name in many ways – dissident, alternative, urgent – are exactly dissidents or alternatives to this pedagogy driven by colonial hatred[15].

For us, conceiving dissident pedagogies has to do with creating a space for self-education that challenges us to constantly pay attention to our own mechanisms of reproduction of this hatred. As well as that which challenges us to create micro and macropolitical strategies that aim to dismantle it day by day, from day to day.

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies. Translation from Portuguese by Roberta Burchardt.

1.

Suely Rolnik is a psychoanalyst and professor at PUC-SP (where she founded the Center for the Study of Subjectivity in the Clinical Psychology Graduate Program). She is dedicated to the investigation of the politics of desire in different contexts and situations, approached from a theoretical point of view inseparable from clinical-political pragmatics. She conceived and produced the Arquivo para uma Obra-Acontecimento (Archive for an Ouevre-Happening), a project to activate the memory of Lygia Clark’s body of work and was the curator, together with Corinne Diserens, of the exhibition Somos o molde. A voce cabe o sopro. Lygia Clark, from object to happening (We are the mold. It’s up to you to blow. Lygia Clark, from object to happening). (Musée de Beaux-arts by Nantes, 2005, and Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, 2006). She was one of the founders of Red Conceptualismos del Sur.

2.

Contrafilé Group emerged as a result of the end of the MICO group, formed by about 20 young people in 2000 in the city of São Paulo. Mico, in Portuguese, has a double connotation: it is a typical monkey in Brazil and also expresses the act of “paying a mico”, making a gaffe, making a fool of oneself, being the object of ridicule and shame.

3.

An idea of Brazilian historiography until recently dominant, and responsible for the dissemination of the false image of the colonizers arriving to a territory not previously occupied – at least, from this perspective, by that which is considered “human”.

4.

Mothers of prisoners, exiles and missing politicians from the last Argentine military dictatorship, who, since 1970 have been fighting for justice.

5.

Hijos e Hijas por la Identidad y la Justicia contra Olvido y Silencio (Sons and Daughters for Identity and Justice against Forgetfulness and Silence). As defined on its website: “H.I.J.O.S. is an independent and horizontal grouping of human rights, formed, in principle, by the children of missing, ex-detainees and exiles of the last Argentine military dictatorship. H.I.J.O.S. fights for justice and punishment of the repressors of the military dictatorship, it stimulates investigations, trials and actions against the repressors. Along with the struggle of other organizations, H.I.J.O.S. inscribed concepts such as those of social justice, active memory and historical continuity. In the mid-1990s, it created the practice of escrache (from the word escrachar) ”. Source: http://www.hijos.org.ar, accessed in February 2021.

6.

GAC was formed in 1997 by young students from Buenos Aies, “from the need to create a space where the artistic and the political are part of the same production mechanism”. In: http://grupodeartecallejero.blogspot.com.br, accessed in February 2021.

7.

[In] the practice of scrache […] the trajectories and spaces of life of the dictatorship repressors are demarcated in the city and evidenced through collective, political, aesthetic and dissemination experiences in the neighborhoods. This practice opened a plural and constant space for action, making possible – based on a new form of political participation – a profound transformation of the social imaginary, and made the human rights policy in Argentina progress (HIJOS, excerpt from its website, accessed March 2012).

8.

Overidentification (Sobreidentificação) is a term proposed by the GAC. The group refers to a type of intervention in which an existing code is used to unfold other meanings. For example, the use of state images (logos, fonts, traffic signs), to express a criticism of the State itself. “As we overidentify ourselves with this institution, we usurp the expected roles and clothing expected from a government institution. […] Each institution, in addition to its concrete meaning, has a symbolic function in cultural grammar, which transmits cultural, social and political values ”(GAC, 2009, p. 158).

9.

To learn more, see: MUSSI, Joana Zatz. Space as Work (Ouevre). São Paulo: Annablume / Invisíveis; Fapesp, 2012.

10.

(Translation note: the word used in the Portuguese original text is “questão”, which implies an “issue”, perhaps more than a mere “question”).

11.

GALINDO, Maria; SÁNCHEZ, Sonia. Ninguna Mujer Nace para Puta. Buenos Aires: Lavaca Editora, 2007, p. 165-195.

12.

Quilombos are communities formed by enslaved people who fled, during the period of slavery in Brazil. Today, there are about 3,500 remaining quilombo communities in the Brazilian national territory, which, like the indigenous peoples, are fighting for the legal recognition and demarcation of their lands.

13.

Rede Mocambos is a nationwide network that connects rural and urban quilombola communities through information and communication technologies.

14.

Name given to the publication that resulted from this process, launched at the end of the Playgrounds 2016 exhibition. Contrafilé Group (org.). A Batalha do Vivo (The Battle of the Living). Edited on the occasion of the Playgrounds 2016 exhibition, São Paulo Art Museum.

15.

This speech by Tatiana Nascimento took place in the context of the workshop, in São Paulo in May 2019, the idea was to establish a space for white activists to critically reflect on their own whiteness, based on urgencies proposed by the mediators.

is an artist, teacher and researcher. Graduated in Geography at the University of São Paulo and Master in Clinical Psychology / Subjectivity Studies at PUC-SP (2017) with the dissertation Beijo de línguas (Tongue Kiss – when the deaf poet and the hearing poet meet) under the guidance of Prof. Dr. Suely Rolnik. Founding member of the art-politics-education collective Grupo Contrafilé and the performance study group Slam do Corpo, which since 2012 has been developing the 1st poetry battle in Brazil with deaf and hearing poets. Since 2000, she has worked training teachers and educators in cultural shows and exhibitions. Cibele develops and participates in projects as an illustrator, working mainly with drawing and embroidery. One of her main quests is to strengthen networks and radical methodologies for meeting, listening and creating.

works as a researcher, artist and educator. Graduated in Social Sciences and Journalism, she has been investigating the relationships between culture, body and urban space in different ways for more than twenty years. In 2012, she defended her Master’s dissertation Space as Work – Actions, Artistic Collectives and City at the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of São Paulo. In 2017, a book with the same title was edited by Annablume with support from Fapesp. This same year, as a Fapesp fellow, Joana defended her doctoral thesis Arte em Fuga (Art in Escape), with focus on the points of convergence between art and social movements today. She founded the artistic collective Contrafilé Group. Since 2000 Joana works as a teacher and coordinator of cultural projects focused on contemporary art education for young people and teachers, from a political and critical perspective, in partnership with different institutions in São Paulo and Brazil.

Formed in São Paulo, Brazil, in the year 2000, Grupo Contrafilé is a collective of art-politics-education production focused on encounters with different people, groups and communities, always from a critical and cartographic perspective and having as main subject of its work listening and performing affections and urgencies. Among its projects, the following stand out: Program for the De-turnstilization of Life itself (2004) and The Children’s Rebellion (2005) – which gave rise to Park to Play and Think (2011) and Backyard (2013); The Tree-School (2014) and The Battle of the Living (2016). Currently, Contrafilé develops the School of Testimonies project (2019-2021). The group participated in several exhibitions, such as: Meta-Archive 1964 – 1985: Space for Listening and Reading Dictatorship Stories (Memorial of the Resistance / Sesc, 2019), Talking to Action: Art, Pedagogy and Activism in the Americas (USA, different locations, 2017-2019), Playgrounds 2016 (MASP), 31st São Paulo Art Biennial (2014), Radical Education (Slovenia, 2008), If You See Something Say Something (Australia, 2007), La Normalidad (Argentina, 2006) , Collective Creativity (Germany, 2005).