The Right to design

Onkar Kular and Henric Benesch

CATEGORY

What is it then to design if you are not a designer? What is it to design if you do not necessarily design ‘things’ which have yet not come into being? Is it the capacity to imaginatively and critically engage with ‘anything’ as something – which systematically, through all sorts of potentialities and lost opportunities – have transcended from non-being to being?

The following text was commissioned for Urgent Pedagogies in 2021 and was prompted by the initial question from IASPIS to contribute with an issue to the developing Urgent Pedagogies platform. While much has happened since, the argumentation in this text, centred around the limits and possibilities of design as discipline and as areas of expertise in relation to education and pedagogies, is still valid. It is a further elaboration on the ideas in our original reworking of Arjun Appadurai´s 2006 paper, ‘The Right to Research, Globalisation, Societies and Education’ to the Right to design, setting the foundations for the platform. It was through the writing of this text the issues of readership and design literacy were articulated more clearly, issues which have held a prominent position throughout our practice within the platform. Picking up the text again we have also come to realise that this text surely would have been another text if we were to write it now, and maybe we will do a new version in the future. As of now, we have chosen to keep the text in its original form, with minor amendments, hoping it can age gracefully.

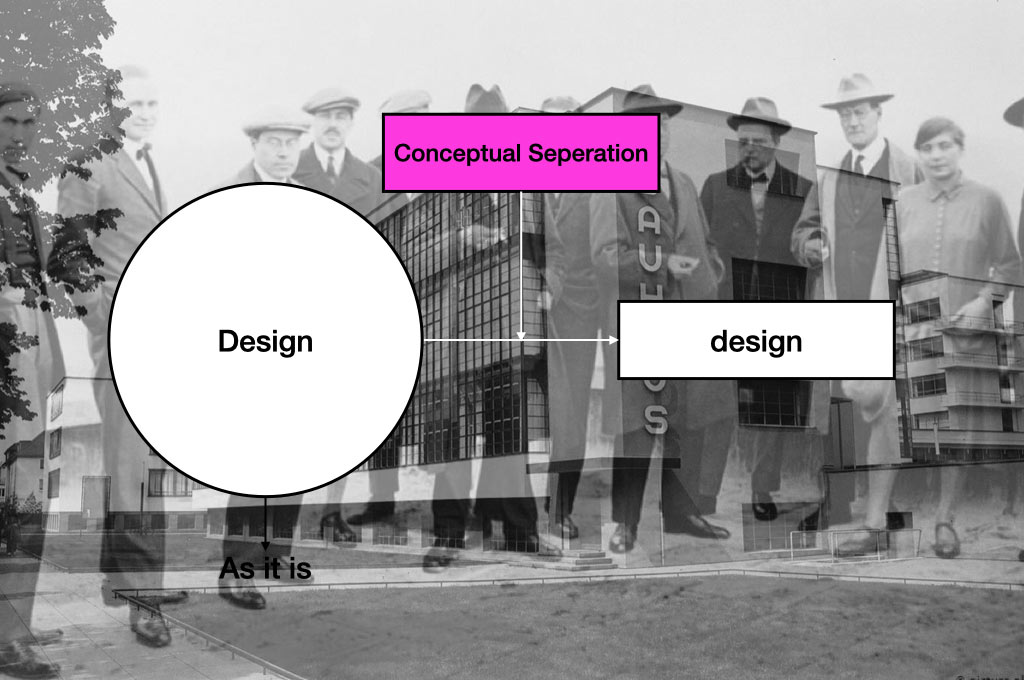

Image from A Purposeful Misreading Video, PARSE Journal 12, Human, 2020.

What is the role of ‘design’ in the ongoing social, political and environmental crisis? The legacy of designers, amongst others, as stewards of the momentum framed as the Anthropocene, is a heavy burden. Furthermore we might argue that the current COVID-19 global pandemic acutely renders not only the fault lines of systemic inequalities but also brings to the surface the general insignificance of professionalised Design, while at the same time we might argue seeing a significant increase in design activity practised mostly by non-designers.[1] Being at such a pivotal moment in time, may we not foreground the urgent question of whether the future of design is being obstructed by its disciplinary frameworks? As Clive Dilnot ́stated back in 2015 “we never yet had design – only its weak, subaltern industrial-capitalist, version. One reason we have never had design is perhaps that Designers, as well as struggling to exemplify the capabilities of design, also, in some ways, ‘got in the way’ of design. Is the radical conclusion of this then that in the emerging future we shall get to the point where the Designer ‘disappears’ within a wider praxis of designing as a ubiquitous and necessary condition of becoming human?” [2]

Such a perspective on design not only prompts a rethinking of design but also in consequence – of design education as well. Following, it can be argued that design education in its professionalised and vocationally structured arrangements within higher education, as stated by Arjun Appadurai[3] with regards to higher education more broadly, has been one of the main instruments for keeping design firmly in place (within its disciplinary framework) – as clearly the privilege of the few instead of the right of the many.

If design is better off without the designer, as Dilnot suggests, maybe operative models of design education cannot be assumed only to be found within formal design education. On the contrary, the formative perspective of systematically imagining something which as-of-yet is not into existence is to be cultivated wherever it is found, and however, it is formalised or not.

If so, urgent questions we need to address are: where might and does design education reside – (in forms and settings which may not be recognized as design education being too dissimilar from formal design education)? How can these forms of design education be brought to attention, cultivated and enhanced? Are there other settings where design education should and could reside, and if so, how can that come into being without being hampered by current institutionalised models?

The Right to design platform, while emerging from the disciplinary frameworks within higher education it seeks unsettle, is informed by the ethos that these questions should not be viewed as hypothetical nor rhetorical, but asks of us, not only proper answers but also actions – of all sorts. In addition, it is informed by the recognition that design education in its current forms and arrangements (within higher education), with all its privileges, has a particular responsibility to shift this landscape, to work from within. What has been a privilege – to be a designer – should, in fact, be considered an obligation – to un-discipline design – in order to establish a right, the right – to design on a broader ground.

While the ambition to look beyond formal design education in order to get a sense of design education proper, might indeed be fraught with disciplinary ballast and prejudice, through curiosity and action we put faith in public enquiry and take comfort in the fact that formal design education cannot and should not address this alone.

What is it then to design if you are not a designer? What is it to design if you do not necessarily design ‘things’ which have yet not come into being? Is it not the capacity to imaginatively and critically engage with ‘anything’ as something – which systematically, through all sorts of potentialities and lost opportunities – have transcended from non-being to being? What if design is not only about utterance and authorship (as historically cultivated within formal design education), but about interpretation and readership (as well)?

Today, the ability to ‘read’ design through, with and in-relation to all sorts of lenses; economic, historical, political, intersectional, decolonial, post-human, within formalised design education is marginally cultivated within the area usually referred to as “Design studies”. However, in many ways it is again, similar to design more broadly, an area which has limited itself (and its imaginary) to its disciplinary and institutional boundaries, as typified by this definition of Design studies by Cameron Tonkinwise: “The job of Design studies is to expose design students to a range of values, often to the values at work in what appear to be neutral, functional, or merely beautiful design decisions.”[4]

Thought differently, and positioned within a broader un-disciplined landscape, the question of Design studies could be raised as a question of literacy or more specifically design literacy. As a form of readership and the “ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute”[5] design more broadly not only within formal design education but also at sites where such a capacity already is, or ought to be cultivated, for instance within basic education, post-compulsory educational settings or other public institutions, formal as well as informal, organised as well as self-organised, established as well as emerging.

This brings us back to the question of the ‘right to design’. Given that we live on a planet where Design is more pervasive than ever before and the significant role that design plays in ongoing social, political and environmental injustices, the particular “right” of interest here is the idea that the ability and capacity to ‘read’ design is not and should not be limited to the concern of Designers alone.

The Right to design in this context propositionally includes two shifts. First of all, the acknowledgement that design indeed is ‘read’’ in a variety of contexts where people do not consider themselves as designers or relate to a design context at all, we can already see this within certain parts of academia – for instance within the social sciences, law, economics, psychology, and so forth but also, outside – amongst non-design professionals in all sorts of organisations, companies, as well importantly, organically from citizens in their daily interaction with ‘design’. Here, given the epistemological and ontological nature of the current crises, the capacity to ‘read’ across those sites and perspectives are crucial for socially, culturally and economically transformative actions to come into being not only for more informed ‘citizenship and activism’ but also essential for more informed ‘scholarship’, and more informed ‘professional practices’. Secondly, the recognition that the cultivation of the capacity to ‘read’ is unevenly distributed across those sites and perspectives. Such an argument does not include a ‘flattening’ of ‘readership’ but rather an acknowledgement that there are different forms of design readership, which first of all should be respected, and secondly be supported in ways which can foster a reading ‘across’, not only as passive reflexive modality, but as a prerequisite for more informed and imaginative actions to both understand and respond to the designed conditions of our crises and furthermore in connection to what Arjun Appadurai calls the “capacity to aspire” and imagine beyond.

In consequence, The Right to design platform is also a commitment to look into and develop a broader definition of design education which is a) not limited by its disciplinary frameworks and institutional settings and b) reimagines design across a readership spectrum in contrast to the dominant authorship spectrum. Here it would be a mistake to understand an authorship model as necessarily being more active or progressive than a readership model. On the contrary, the point of departure for The Right to design is that the current lack of progression with Design is directly related to absence of a broader capacity and interest to read design across domains and together with others.

In this sense, the immediate ambitions of The Right to design platform are two-fold. Firstly, by foregrounding readership and issues of design literacy, a broader understanding of design education can be cultivated beyond design and design education’s current institutional and disciplinary confinement. And secondly, through the same mechanisms, design education can be revitalised and enriched, transcending and transgressing its current disciplinary cage to meet urgent challenges of today. Where at best, to once again use the words of Clive Dilnot: “The world loses Designers but it gains design”.

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

It could be argued that whilst professionalised design has mostly found itself redundant during the global pandemic, we have seen within this planetary condition a sharp increase in design thinking and activity practised by individuals, groups and professions that would not necessarily associate themselves to design and the Design profession. As a snap-shot of this activity we could point to the remodifying of homes into rapid sites of work and education, the re-spatialization and remodelling of workplaces to ensure proximity and hygiene between employees, to the temporary replanning and ‘hacking’ of urban environments at all scales, from cafes to playgrounds to limit critical mass.

2.

Clive Dilnot (2015) The matter of design, Design Philosophy Papers, 13:2, 115-123, DOI:10.1080/14487136.2015.1133137

3.

Arjun Appadurai (2006) The right to research, Globalisation, Societies and Education, 4:2, 167-177, DOI: 10.1080/14767720600750696

4.

Cameron Tonkinwise (2014) Design Studies—What Is it Good For?. Design and Culture, 6(1), pp.5-43.

5.

UNESCO. (2006) Education for All: A Global Monitoring Report Chapter 6: “Understandings of Literacy” p.147-159

is a practice-based research platform run by Onkar Kular and Henric Benesch. The platform has the dual aim of understanding the entangled historic and present relationship between design and rights and to claim ‘design’ itself as a special kind of right that is accessible beyond class background, gender, ethnicity, age, and disability. The platform currently serves as the base for activities such as assemblies, (mis)readings, broadcasting and educational initiatives with partners inside and outside academia.

is Professor of Design at HDK Valand, Academy of Art & Design and Programme coordinator for PLACE (Public Life, Arts, Critical Engagement) at the Artistic Faculty, University of Gothenburg. His research is disseminated internationally through commissions, exhibitions, education, and publications. His work is in the collection of the CNAP, France, and Crafts Council, UK. He has guest-curated exhibitions for The Citizens Archive of Pakistan, Karachi, and the Crafts Council, UK. He was Stanley Picker Fellow 2016 and Artistic Director of Gothenburg Design Festival, Open Week 2017 and Co-Artistic Director of Luleå Art Biennial 2022.

is an associate professor (docent) in Design at HDK-Valand—Academy of Art and Design—acting Dean at The Artistic Faculty and an associate of Centre for Critical Heritage Studies (CCHS) at the University of Gothenburg. He is an architect interested in socio-material, spatial, and temporal aspects of knowledge regimes and (co-)creation of knowledge with a particular interest in situated and speculative methodologies. During 2023, together with Onkar Kular, he participated in “The Public Design Office”, an ArtInsideOut Residency in Falkenberg (SE). Recent publications include “The Right to design” (2020), “What if a 1%-rule for Public Design” (2021), and “Co-curating the city: universities and urban heritage past and future” (2022).