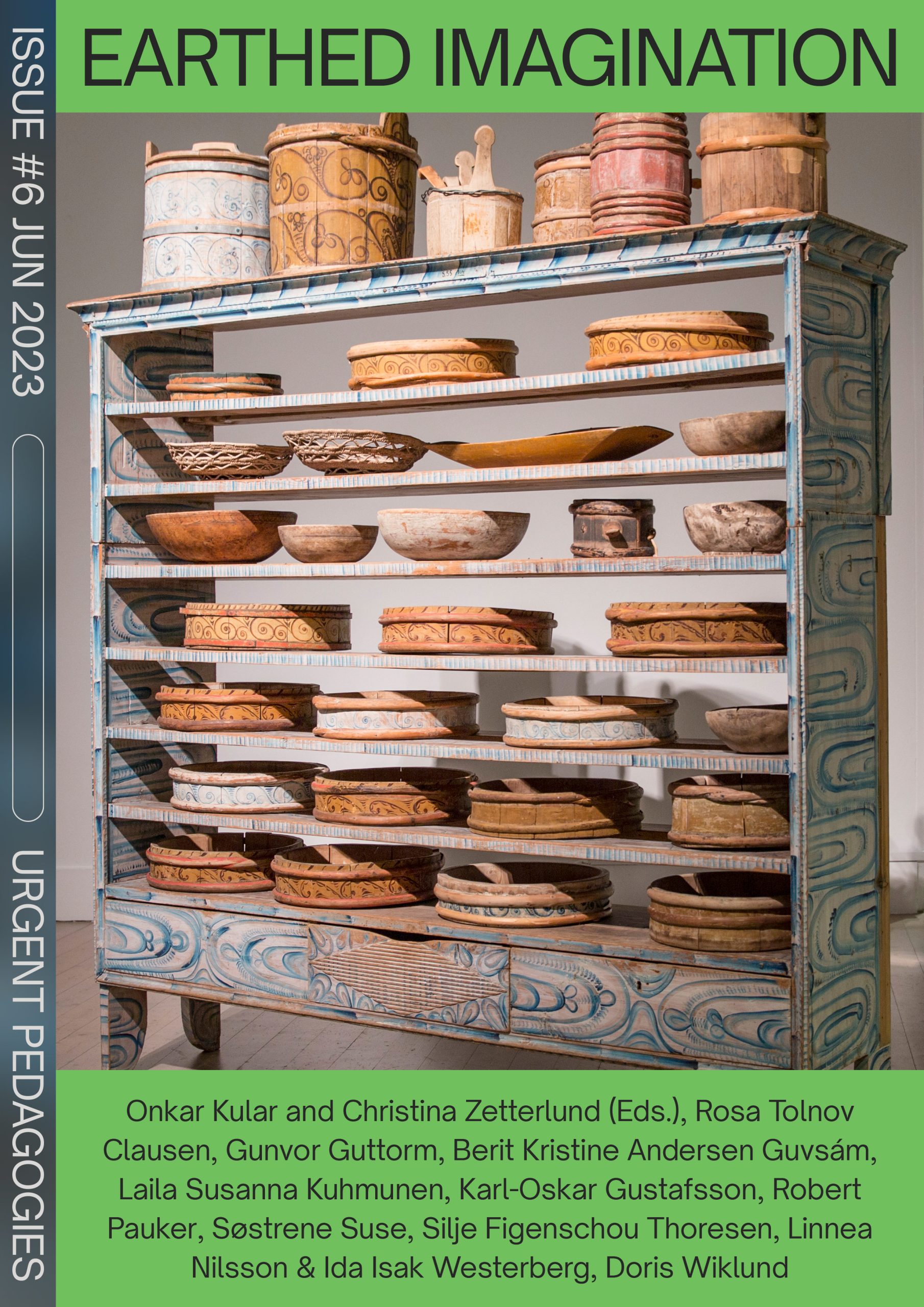

Issue #6

Earthed Imagination

Onkar Kular and Christina Zetterlund (Eds.), Rosa Tolnov Clausen, Gunvor Guttorm, Berit Kristine Andersen Guvsám, Laila Susanna Kuhmunen, Karl-Oskar Gustafsson, Robert Pauker, Søstrene Suse, Silje Figenschou Thoresen, Linnea Nilsson & Ida Isak Westerberg, Doris Wiklund

CATEGORY

Welcome to Issue #6: Earthed Imagination, guest edited by Onkar Kular and Christina Zetterlund. Earthed Imagination looks back at Luleå Biennial 2022, Craft & Art to consider the different ways the biennial engaged and facilitated learning and collective imagination through its physical and digital Learning Room platform and programme.

Luleå Biennial 2022, Craft & Art was hosted by Konstfrämjandet (The Peoples Movement for Art Promotion) and took place in Norrbotten between October 15th, 2022 – January 15th 2023. Recognizing the expansive geography of the Norrbotten region in northern Sweden, a biennial Learning Room was set up as a physical and virtual space to share knowledge from different perspectives and places. Alongside a Festival and Exhibitions, the Learning Room was one of three formats through which the biennial was mediated and engaged through. All acting as formats for listening and learning with Norrbotten and its people. The Learning Room invited guests to talks, film screenings, making circles and workshops of many varieties. As such, it provided the space to work with practices and organisations that did not find a natural home within the traditional exhibition format. This was especially important since the biennial developed from being a contemporary art event to also include craft within the 2022 edition.

Installation View of Luleå Biennial 2022, Craft & Art, Havremagasinet Länskonsthall. Straw Crafts from Berits Halmmuseum at the Sörbyn Sundsnäs Homestead Museum, Johannes Samuelsson, Bärtider, 2012–2022 Photo: Thomas Hämèn.

Critical to the inclusion and our framing of craft was that it was not something that was defined in relation to art, a relation that we felt would confirm a long historical hierarchy within western art history and adhering to arbitrary splits between the arts. Instead, we situated craft in a broader landscape of making that included everything from food preparation and weaving, car modifications and wood carving, straw craft, and jewellery. Our interests concerned a definition of craft that exists within the everyday, regardless of practitioner’s origin, class, and education.

Listening widely was a vital ingredient in the biennial. We decided from the onset that it would be problematic to impose an outsider frame on a geography that has a complex history and one that we neither live nor were born in. Instead, we began to work with the biennial by listening and learning with Norrbotten, to locate stories and important questions found within this geography. Story threads that we could weave, spin and knot together. To focus our ears and find a direction for listening we formulated four principles for the development of the biennial. The principles steered us, allowed us to find a common language to share, and at times were helpful reminders on how to act:

Beyond Border Thinking was to think beyond established boundaries between crafts and arts, to go beyond sharp divisions between practices, peoples, traditions, and places. This was especially translatable to the Swedish field of craft where it has been common to divide craft practices into different parts such as konst, konsthantverk, slöjd, and hantverk (art, craft, sloyd, and handicraft), all identifying labels that now have their own institutions and in many cases histories. It is a division of the handmade that comes from a western modernity, of a nation-state forming various institutions. For the biennial it was vital to go beyond these borders and take the hand and the handmade as a point of departure and a lens that one can listen through.

Beyond Border Thinking was also formulated in relation to the biennial being situated in the north of Sweden, where until the Covid pandemic, borders were porous in some respects, allowing movement between the Nordic countries. Here, in Sápmi, an area that was colonised and subsequently divided with the development of the modern nation-state. Through the biennial we were keen to research how borders structured land as well as practices, ultimately aiming to work and engage with artistic practices that transcended borders of countries, institutions, and identities.

Decentering was to identify and understand positioning, ultimately with and through listening. To engage with practices, knowledges, and sites not through predetermined hierarchies but rather through practices of wide listening. To listen and learn in relation to the site with the aim of understanding its complexity. This was about who gets to be invited into the process and ultimately who felt invited to the biennial – and to ask the question, who is the biennial relevant for?

Custodianship was to collectively consider the overall ecology of the biennial. To foreground its history, its present, and its distant future. And within this time-based constellation to recognise that an art biennial is a matrix of human, non-human and environmental conditions that need to be respected, cared for, and nurtured. This was both about the content of the biennial and the organisations, audiences, contexts, and the people that put together such an event. This required that we worked towards a good working environment for everybody when producing the biennial. To be resourceful with materials and material practices that are used within the production of the biennial itself, from materials and energy used to create exhibitions, to the knowledge and information that was produced by participants and audiences within the biennial. Also, to recognise that a biennial is an archive-making activity, and subsequently to consider how a biennial can be used as a resource for the future for guests and hosts.

Our last principle Earthed Imagination is also the title of this issue. Anthropologist Arjun Appadurai describes imagination as not just an individual faculty for escaping the real, but as a social practice and collective tool for the transformation of the real and for the creation of multiple horizons of possibility [1].

He also describes collective imagination as something that is fundamentally connected to where one locates oneself. Framed as such, collective imagination therefore begins from the earth and the grounds on which we congregate and find ourselves. Within the biennial, we viewed craft as fundamentally about the ‘earth’, from the materials used, to the sites of where craft is practised. Earthed Imagination is therefore to consider craft as a social practice of imagination that allows us to not only to think about the world we inhabit, but to dream the world we would like to inhabit, and, as good ancestors, a world we would like to leave behind.

Installation View of Luleå Biennial 2022, Craft & Art, Norrbottens museum. Elena Mazzi, Sápmi Flatbed, 2022, Silje Figenschou Thoresen, Der traff ikke kvist, 2022, Vandret Linje, 2017-2020 Photo: Thomas Hämèn.

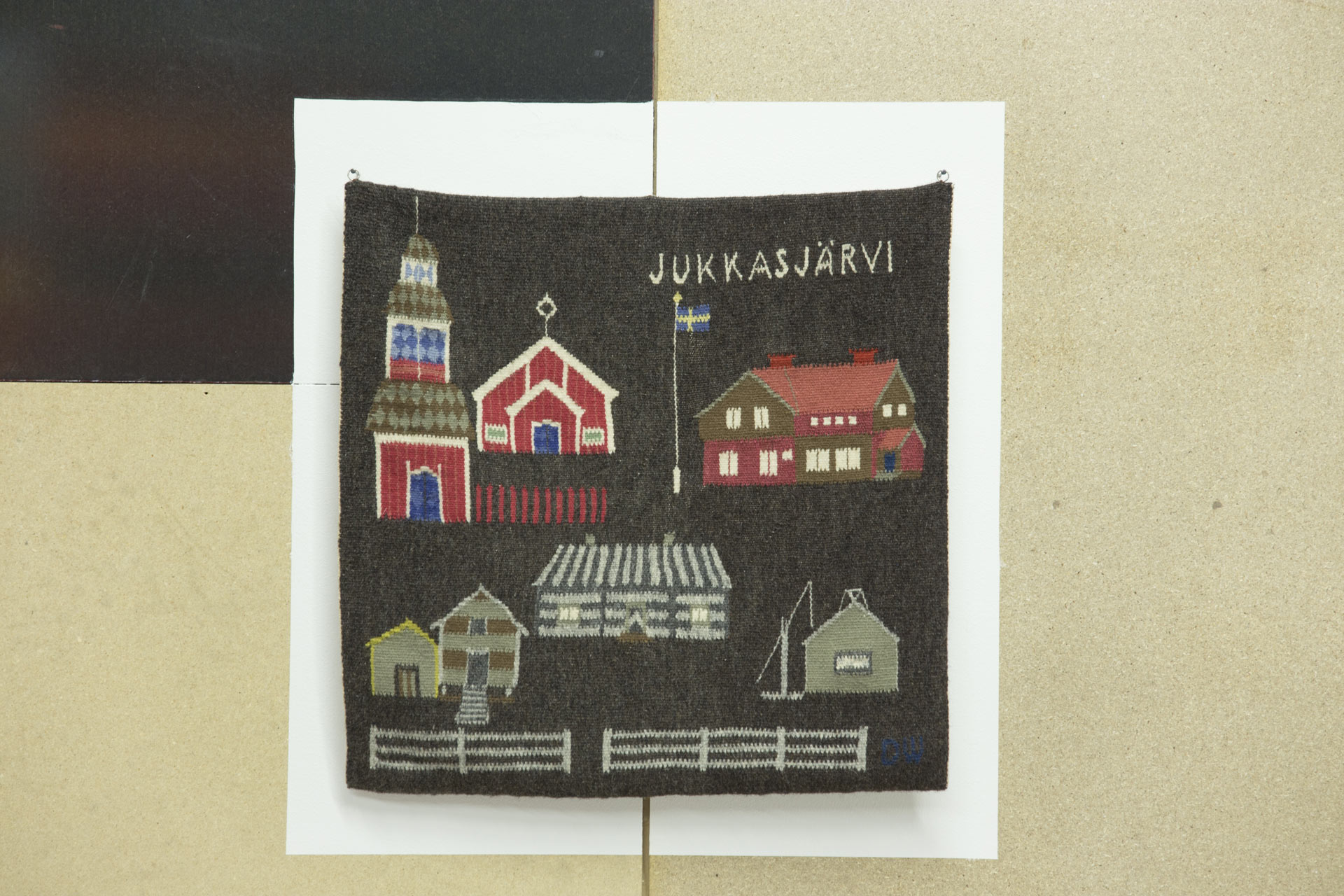

In the process of making the biennial we listened to numerous stories and learned about a variety of creative practices and complex histories. There is a dense richness within the region of Norrbotten that was a great privilege to work with and understand. Through this process, many gave their time and we are grateful for their generosity. These stories became the backbone of the biennial, mediated through the Learning Room, Festival and Exhibitions. The Exhibitions took place at Galleri Syster, Havremagasinet Länskonsthall in Boden, Luleå Art Gallery, Norrbottens museum and Pontusbadet. The biennial also hosted a Festival, stitching together a map of regional connections through workshops and seminars across multiple venues. The Festival contributed to broadening the biennial narrative and created a dialogue with the Learning Room and Exhibitions. Within the Festival we invited various organisations with their own specific and situated knowledge to curate exhibitions within the biennial. Here, the biennial attempted to decentralise its normal operation to go to places where craft practices in-situ tell their own compelling stories. Within the Festival we had the opportunity to learn and work with the Sami Duodji Sami Craft Foundation, Kiruna municipality’s art collection, Jukkasjärvi parish, Sámi Dáiddaguovddáš Foundation, Korpilombolo’s Cultural Association and local historical homestead museums of Sörbyn Sundsnäs and Aunesgården. The Festival began on the opening weekend with an invitation to guests to ice skate together, eat blueberry porridge, listen to an organ concert at Jukkasjärvi church, attend a making circle and dance at the self-organised Luleå Punk-House.

Installation View of Luleå Biennial 2022, Craft & Art, Luleå Konsthall. Susan Schuppli, Ice Cores, 2019, MADAM cabinetmakers and furniture restorers, Tack Skogen! (Thank You, Forest!), 2022 Photo: Thomas Hämèn.

When we started to work with the biennial, we began by listening to the biennial itself, revisiting its origins as a winter art biennial for ice and snow. Through the lens of craft, we paid particular attention to the material conditions of ice and snow and how our understanding of these materials has changed over the years. Here, we located our first working thread, ice and snow, and how the production of artificial cold through refrigerated transportation and storage is central to our way of life, global economics and politics. Ice and snow are very much a part of Norrbotten, there are many creative practices of working and living with this environmental material and a diverse language to describe its many nuances. Over the past years, melting ice has become one of the emblematic images of climate change. However, climate change is a very tangible condition within the region and already impacts a way of life that has existed since time immemorial.

Along with the everyday realities of climate change, Norrbotten is a landscape characterised by various forms of extractivism, our second thread. Climate change is predicated on a long history where humans, predominantly in the Global North, have lived beyond the Earth’s resources. These are assets that have been extracted in places other than where they have been consumed and the economic profits have been accumulated. The wounds in the lands are deep and continue to deepen. We followed this winding circular thread as it continues to unravel into the region’s plans for a green energy future, where we see the building of fossil-free energy initiatives, large-scale forestry, wind farms and mining through the continued pursuit of growth. And at the same time, the logics of extractivism apply to arts and culture where there is an extended history of observing Norrbotten from a distance, from the outside. Here the principle of custodianship became particularly important and where possible we sought to form a biennial with Norrbotten, creating space for many different perspectives to be heard.

Working with Norrbotten meant spending time with complicated histories. In many historical accounts of the region, the “wasteland” is a recurring theme for writers, researchers, and artists alike. An imagined wasteland that lacks traces of human presence or activity and a landscape depicted as “empty” with its resources waiting to be used. Norrbotten has never been empty, the relationship to the lands has looked different here from the understanding of the writers, researchers and authors that have tried to capture this diverse landscape. A consequence of this relationship is that identities have been essentialised in politics such as the Sami-shall-be-Sami politics. Adding to this is also the hardline assimilation policies against Tornedalians, Kvens and Lantalaiset who have had experiences and histories erased. We should not forget that 2022 marked one hundred years since the State Institute for Racial Biology was founded, a national institute that was very active in Norrbotten measuring and mapping its inhabitants. At the same time, there is a fantastic wealth of creative practices that exist and have existed in Norrbotten, deep stories that the landscape carries and networks. These are stories where people have not lived separately but supported and depended on each other.

And with this, we spun our last thread, crafting beyond the wasteland. It emerged through conversations with artists, crafters and organisations who had expressed a frustration in the erasures of histories, essentialisation of identities and marginalisation of knowledge. These conversations articulate how the nation-state’s violent categorisations of people and materials has been reflected in how history itself has been written, as well as how resources and power have been distributed. We collaborated with practices and organisations from craft and art that go beyond borders, challenge established categorisations and historical understandings. There are gestaltningar and projects where Norrbotten, through diverse practices, narrates its own stories about difficult histories, the joy of making and an Earthed Imagination. In crafting beyond the wasteland, we wanted to foreground that this is not a history that is unique to Norrbotten, but it has been a colonial trope, a prerequisite for claiming land and controlling people in many geographies. That is to say, it is not just a wasteland but wastelands.

Installation View of Luleå Biennial 2022, Craft & Art, Luleå Konsthall. Rosa Taikon, Ring, 2000, Necklace, 1970’s, created in collaboration with Bernd Janusch, Ring, 1960’s, MADAM cabinetmakers and furniture restorers, Tack Skogen! (Thank You, Forest!), Katarina Pirak Sikku, Katarina Pirak Sikkus arkiv: Förmödrarna Piraks, Segals och Klemetssons duodje skatter, (“Katarina Pirak Sikku’s Archives: the ancestors Pirak’s, Segal’s, and Klemetsson’s Duodje Treasures”), 2022, Photo: Thomas Hämèn.

During the biennial, the Learning Room was a testing ground to generate new insights and knowledge with crafters, artists, and regional organisations. Through the physical and digital Learning Room we invited diverse practices and staged a multitude of collaborations with places, persons, organisations, and thus creating a resource for the future for guests and hosts. During the final weekend of the biennial, we ran a finnisage event Earthed Imagination as an opportunity to invite back biennial collaborators and friends to consider how collective imagination operated through making, acting, and sharing throughout the biennial. The event forms the backbone of this issue with contributions in film, music, recorded talks, and texts. All reflecting how the biennial centred listening and learning in different formats, and acted as a structure for social practice allowing for collective imagination to take place.

The first contribution, Gamla vävnader från Norrbotten (Old Weaves from Norrbotten) is a short text about weaver and educator Doris Wiklund. An influential and important figure in Swedish craft history who, together with her students, created an expansive archive of traditional weaves from Norrbotten. The archive acknowledges and foregrounds a history that for many years has been as overlooked as Norrbotten itself, historically, an area that was perceived as a wasteland. The traditional weaves provide not only a detailed insight into the diversity of skills and making but also a compelling account of daily life in Norrbotten.

Installation View of Luleå Biennial 2022, Craft & Art, Havremagasinet Länskonsthall. Ida Isak Westberg, Sompasenvuoma, 2021 Photo: Thomas Hämèn

As part of the biennial, Linnea Nilsson, Region Norrbotten’s craft and design consultant, in collaboration with textile artist Ida Isak Westerberg, invited the public to a three-part online weaving circle. Together they developed a format where the participants, digitally, were invited to learn to weave across time and geography. Here you have the opportunity to listen to their inspiring talk “What a fantastic way to explore the possibilities of weaving together (but at a distance)” where they present their teaching methods and consider how collective weaving can be rethought and made more accessible through social media.

Rosa Tolnov Clausen set up a Weaving Kiosk, a format inspired by Nordic kiosk culture, in Rajala på gränsen, a shopping centre located in and between the twin towns of Swedish Haparanda and Finnish Tornio. The Weaving Kiosk was made possible through a lively on-going cross-border collaboration between Haparanda City Cultural Department and Aine Art Museum. As part of the collaboration, the biennial invited its digital producer and filmmaker Karl-Oskar Gustafsson to produce a film around the Weaving Kiosk. The film provides a detailed oral and visual narration into the complexities of setting up and running collaborative making spaces.

Gulahallan ja birgen provides an insight into making and learning with researchers and practitioners Gunvor Guttorm, Berit Kristine Andersen Guvsám, and Laila Susanna Kuhmunen. The contribution includes a commissioned film, directed by Karl-Oskar Gustafsson that reflects on collective learning with the AIDA archives (Arctic Indigenous Design Archives) and follows the trio in preparation for an exhibition at Sámi Dáiddaguovddáš Dáiddaguovddáš (The Sami Center for Contemporary Art). The film is accompanied by a text authored by Gunvor Guttorm further contextualising the exhibition and works around the concepts of Gulahallan and Birgen.

Making a direct connection with roots, Silje Figenschou Thoresen’s sculptural works were placed in various locations through the biennial. Hanging from walls, standing on floors, and wedged into the cracks and surfaces of the biennial buildings. In her practice, learning has a special and site specific meaning with her installations becoming an archive that reconsiders linear and traditional knowledge systems. A stick is never too long or too short, is both the title of a recorded talk at the Earthed Imagination finnisage and a commissioned text by Garland Magazine as part of its collaboration with Luleå Biennial 2022.

Installation View of Luleå Biennial 2022, Craft & Art, Havremagasinet Länskonsthall. Silje Figenschou Thoresen, hele strekningen e beskrevne trækul eller sort jord blev ikke iagttaget, 2021. Liu Chuang, Bitcoin Mining and Field Recordings of Ethnic Minorities, 2018 Photo: Thomas Hämèn.

Collective and social imagination is not only limited to humans and this narrow way of understanding collectivity. Learning collectively with the land, with ‘roots’ and place is an important aspect in both Gulahallan ja birgen and Silje Figenschou Thoresen’s practice. Historically, there has existed knowledge about the lands where an interplay and respectful relationship between humans and nature was marked by reciprocity of giving and taking, an extended practice of listening and learning with the land. Earthed Imagination event invited food crafter Eva Gunnare to stage A journey to learn about the land through food, inviting us on a journey to see beyond the trees, to get to know about traditional food practices and to listen and learn with herbs and berries. Through food craft, Eva Gunnare introduces us to ways of seeing to understand lands with traditional knowledges.

Acknowledging that the lands are vulnerable to the circular practices of extractivism threatening lives and age-old practices, as part of the Luleå Biennial 2022, audiences were invited to Baajh vaeride årrodh! (Let the mountains live!). An audio cinema by Søstrene Suse which narrates the story of three generations of women fighting extractivism within Sápmi. The story departs in the Alta conflict, a struggle regarding the expansion of hydroelectric power in the Alta River that began in the 1970s. The audio cinema acts as a format for intergenerational learning, to listen and start conversations about complex questions.

Listening carefully and beyond words can be an opportunity to access hidden and marginalised histories. The final contribution to this issue is an organ concert recorded at Jukkasjärvi church. The church is situated in the small village of Jukkasjärvi, Norrbotten, with its main claim to fame being a Bror Hjorth altarpiece artwork donated by LKAB (Sweden’s state-owned mining company). Organist Robert Pauker performs at Jukkasjärvi Church directs the spotlight elsewhere towards the church organ that was finished with designs by the Sami craftsman Lars Levi Sunna with an abundance of meaningful and symbolic details. When designing the organ’s stop tabs, which are operated to alter the sound of the organ, Sunna listened carefully to each register and designated a fitting symbol from the Sami visual idiom to each one. The organ represents a comprehensive fusion of Sami and Christian imagery, resulting in a statement about the coexistence of these different worldviews that share such a complex history. On 24 November 2021, archbishop Antje Jackelén formally apologised to the Sami community on behalf of the Swedish Church, expressing regret for the church’s role in Sweden’s colonial history.

Contents

Gamla vävnader från Norrbotten (Old weaves from Norrbotten)

Doris Wiklund

Digital weaving circle – What a fantastic way to explore the possibilities of weaving together (but at a distance)!

Linnea Nilsson and Ida Isak Westerberg

Weaving Kiosk on the border at Rajalla Shopping Centre

Rosa Tolnov Clausen

Gulahallan ja birgen

Berit Kristine Andersen Guvsám, Gunvor Guttorm, Laila Susanna Kuhmunen

A stick is never too long or too short

Silje Figenschou Thoresen

A journey to learn about the land through food

Eva Gunnare

Baajh vaeride årrodh! (Let the Mountains Live!)

Søstrene Suse

Organist performance at Jukkasjärvi Church

Robert Pauker

1.

2002 “The Right to Participate in the Work of the Imagination” (Interview with Arjen Mulder), TransUrbanism: 33-46. Rotterdam: V2_Publishing/NAI Publisher

is Professor of Design at HDK Valand, Academy of Art & Design at the University of Gothenburg. His research is disseminated internationally through exhibitions, education, and publications. He has guest-curated exhibitions for The Citizens Archive of Pakistan, Karachi, and the Crafts Council, UK. He was Stanley Picker Fellow 2016, artistic director of Gothenburg Design Festival, Open Week 2017, and co-artistic director of Luleå Art Biennial 2022.

is craft and design historian with an interest in history writing practices where craft and design become a lens for analysing social situations. She is active as associate professor at the Department of Design, Linneaus University as well as an independent curator. Currently she is curating the re-searching project (Re-)learning the archive at Designarkivet Pukeberg

is a textile designer and PhD researcher who works in the intersection of craft and design. She often creates physical spaces around the practice of handweaving, using craft as a catalyst for physical, social, and creative interactions.

works as a cultural guide and food creator with Jokkmokk as her starting point. In 2010, she was educated in Sámi food under the leadership of Greta Huvva at Sámij åhpadusguovdásj (the Sámi Education Center). Since 2011, Gunnare has run Essence of Lapland.

is a professor of doudji at the Sámi allaskuvla/Sámi University of Applied Sciences in Kautokeino. She does practical duodji work alongside writing about the practice of duodji and its role in Sami society.

who has a master’s degree from Sámi allaskuvla, works in Kautokeino today. In her duodji work, she uses materials like textiles and hides.

takes a variety of approaches to duodji. Her explorative and experimental work happens at House of Duodji, which is based in Jokkmokk.

is a Stockholm-based Artist Filmmaker working with choreographed documentary, film adaptations of stage work and digital content for Art Institutions.

is a composer, organist and musician based in Kiruna, Sweden.

is a collective that consists of journalists Astrid Fadnes, Ingrid Fadnes, Eva Maria Fjellheim, and Susanne Normann. They have collaborated on various projects in South America, Norway, and Sápmi in which they have addressed issues like feminism, extractivism, and the autonomy and territorial struggles of indigenous peoples.

is an artist working in Kirkenes in Østfinnmark in Northern Norway. Her artistic practice encompasses installation, sculpture, and drawing, and is often determined by the materials she works with.

works as a Craft and Design Consultant in Region Norrbotten with the mission to promote crafts in the area. She creates activities aimed at a broad variety of target groups, including children and youths, hobby practitioners, as well as professional crafters. An important part of her job is to make craft available and inclusive to people who usually do not participate in the practice.

is an artist, craft practitioner and pedagogue. Their practice is based on Norrbotten and queer perspectives and seeks to explore various aspects of belonging by means of a union of weaving, learning, and collaborative creation. Ida Isak Westerberg’s was trained in weaving and artistic embroidery at Friends of Handicraft in Stockholm and has been living and working in Älvsbyn in Norrbotten since the fall of 2018.

who was born in Kiruna in 1930, is a weaver and educator. She trained at Friends of Handicraft, and spent many years working as a weaving teacher in Kiruna. She has published four books about her own weaves and historical weaving. Outside of Norrbotten, her work has reached an international audience, partly as a result of one of her books being translated to English.