bildungsLab*: Redefining Art and Pedagogy from the Margins

María do Mar Castro Varela and Saphira Shure

CATEGORY

“They are bored. We aren’t. We are intellectuals who do not seek recognition but want to change the world. We experiment, we think, we speak up even when we are not given the floor.”

Art is an important field of knowledge production. European artistic research relies on a Eurocentric canon meanwhile the majority of art schools worldwide continue to be rather feudal institutions. Questioning these structures is one of the main topics the bildungsLab* (bLab*) deals with. Founded in 2017 by María do Mar Castro Varela as a contribution to “Schools of Tomorrow” – a project by Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in Berlin, bLab* is concerned with questions such as: How could and should schools look like? What is the role of art in future educational institutions?

The role which education acquired in propping up imperialism should not be underestimated. Education was after all applied as ideological pacification, for which the traditional knowledge and everyday practices of the colonized were lastingly (re-)coded.

bLab* is a collective of BIPoCs and migrant women* who are activists, work in academia, are artists or work in the field of art education. bLab* intervenes into hegemonic knowledge production and offers alternatives to the functioning of the hegemonic teaching machine.

As we know, the hegemonic culture accepts BIPoC and migrants only as tokens. One or two BIPoC’s per institution, one exposition per year on non-Eurocentric art productions, one or two conferences on postcolonial theory, etc., but we want to be more than just the decor of a non-performative diversity strategy that stabilizes the socio-political structures without changing the ethico-political frame. bLab* produces theory without negating the heterogeneity of experiences.

Inspired by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak we understand education as an “epistemological project” which can be described as an “uncoercive re-arrangement of desire” (Spivak 2012). Rethinking the multiple experiences of migration, racism, classism and (hetero)sexism, bLab* thinks of education as a practice of re-imagining the world. We are interested in how schools can be transformed into places where education becomes desirable. Which desires have to be rearranged and how? How may it be possible to challenge the canon? How will it be possible to achieve an epistemological change? We advance these questions from inside the teaching machine making use of different theoretical approaches and strategies: deconstruction, dialectical, feminist, Marxist, postcolonial, queer etc. Whatever helps us to analyze hegemonic structures, with the aim to produce rifts in the violent structures, is put to use.

bLab* questions hegemonic educational practices as well as educational institutions from a postcolonial perspective. We don’t follow the idea that there is only just one right way to go to find the right answer to all global problems, but questioning remains paramount to us. We are skeptical of the promise universal theories offer, while ignoring positionality and perspectivity. Inspired by Michel Foucault, we understand problematizing as a method and strategy which points to a social understanding of why and how specific social groups and practices became a problem. By making migrants and BIPoCs to be a problem they are pushed to the margins.

As a collective, bLab* tries also to overcome the sense that particular experiences of violence are more important to tackle than others. We confront ourselves with the dependency towards the Other. Our experiences of discrimination are woven into global structures of injustice. Class is paramount when it comes to acquiring education. Most students who grew up in proletarian, marginalized families straight forward reject education – sometimes out of frustration, sometimes as an act of resistance. Whatever the reason may be, the consequence is always the stabilization of the status quo: social mobility is made impossible. bLab* explores the possibilities of making education attractive to those who reject education, because they experience persistent discrimination in the teaching machine. It is our endeavor to transform education into something that appears desirable not only for the hegemonic group, but also for the proletarian, migrant and queer student. Taking engaged pedagogy (bell hooks) as one of our spurs, strategies are developed that intend to set the teaching machine in motion.

Our guiding concepts are resistance and desire.[1] Desire plays a prominent role in Spivak’s notion of education. The postcolonial theorist assumes that educational institutions produce specifically desiring subjects. Desire is articulated, for example, in the desire or rejection to be part of educational institutions or in the production of knowledge as something desirable. Resistance, on the other hand, is repeatedly undermined within educational institutions by creating a consensus that makes it difficult to even imagine possibilities of non-compliance. Desire and resistance are closely related but are rarely considered in debates about education. One of our concerns is to enable other forms of knowledge production speaking publicly from the perspective of outsiders inside the teaching machine. Discussing migration, racism, class, (hetero-)sexism and the discrimination of trans, inter and non-binary persons, we want to reduce the violence these communities and social groups are confronted with inside educational institutions.

We are interested in educational spaces that enable processes of collective knowledge production, in which alternative knowledge that challenges the hegemonic knowledge can be discussed, introduced and studied However, an engaged pedagogy will always have to be self-critical. As teachers and artists, we see ourselves not outside power structures. To the contrary, at times we profit from what discriminates against us. Put differently, it is not possible to claim a critical outside perspective. We have to criticize what we inhabit. Teachers, artists as well as educational institutions and museums are part of the imperialist, hegemonic structures. Knowing that makes us sensitive, it makes us vigilant. Responsibility, after all, is particularly important vis-à-vis those we don’t feel to belong to: the Other; the not-us.

The bildungsLab* manifesto.

What we recognize as knowledge on the surfaces, what pushes or is pushed through the layers of history, and what seems to structure the world and life, ultimately remains only a part of the almost infinite forms of knowledge. It is significant to illuminate the power form of narratives about past, present, and future. Knowledge, which for instance underlies remembering and also co-determines its meaningfulness, is in this way also mediated by mechanisms of repression and displacement. Only then does mastery and order become possible in a specific way. Here, too, it is not a matter of asserting the one truth about history, but of debating pasts and memory. As Spivak notes, the point is not to claim that there is no truth but instead to make transparent how truths are formed.

A significant challenge lies in how to negotiate the legacies of Enlightenment like democracy, justice, and emancipation without reproducing the inherent violence that constitutes the core of Enlightenment (see Castro Varela, 2014; Dhawan, 2014). Nativist denunciations of the legacies of Enlightenment and the search for pure, uncontaminated non-Western knowledge systems are a risky option as they feed nationalist fantasies. Despite the entanglement with imperialist violence, we cannot escape the Enlightenment. Spivak, therefore, proposes an “affirmative sabotage” of those Enlightenment principles “with which we are in sympathy, enough to subvert!” (Spivak, 2012, p. 4). Affirmative sabotage is a strategy that turns instruments of colonialism into tools for decolonization. Instead of searching for uncontaminated indigenous knowledge (Said, 1993, p. 228-229), the complicity of institutions of teaching and learning in global injustice needs to be urgently analysed.

bLab* tells stories. Stories that have been around for a long time. We repeat them, we remind ourselves and others of these nearly forgotten stories. We comment on the stories. bLab* wants to get things moving. That’s why one of our main goals is to show how different knowledge has been ignored. We write, give talks, paint, perform, discuss, conduct research, make music, etc. These different practices reflect on language, concerns, vulnerabilities, strengths and goals. The point is precisely not to undo the separation of thinking and feeling. That is why bLab* creates spaces where the entanglement of thinking and feeling is articulated.

We are sure that our thinking will be able to change the world. We don’t suffer delusions of grandeur, but dare to be realistic. The change will not be huge, but Schools, universities and palaces of art do not need to wait for us. They can negate us, but we are already there. We trouble the canon. They know that they need us because their intellectual energy is running out. They are bored. We aren’t. We are intellectuals who do not seek recognition but want to change the world. We experiment, we think, we speak up even when we are not given the floor. In times of neoliberalism, climate change and growing racism in Europe, it seems paramount to address the necessity of an education which enables especially marginalized students to deploy their imagination so that they are able to resist growing autocratic ideologies.

bLab* is a space where contrapunctual arguments are exchanged. We love to be argumentative, but it is not about winning. It’s about listening, about making space for those who are excluded. bLab* is an experiment. We experiment: we want to stretch our imagination. Without art, without the aesthetic it will not be possible to see and to articulate the marginalized. We still think that another world is possible: if not yet then tomorrow.

Castro Varela, M. (2014). “Uncanny entanglements: Holocaust, colonialism and enlightenment. In N. Dhawan (Ed.), Decolonizing enlightenment: Transnational justice, human rights and democracy in a postcolonial world. Budrich, , pp. 115–138.

Dhawan, N. (Ed.). (2014). Decolonizing enlightenment: Transnational justice, human rights and democracy in a postcolonial world. Budrich.

Said, E. W. (1993). Culture and imperialism. Chatto & Windus.

Spivak, Gayatri C. (2012): An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

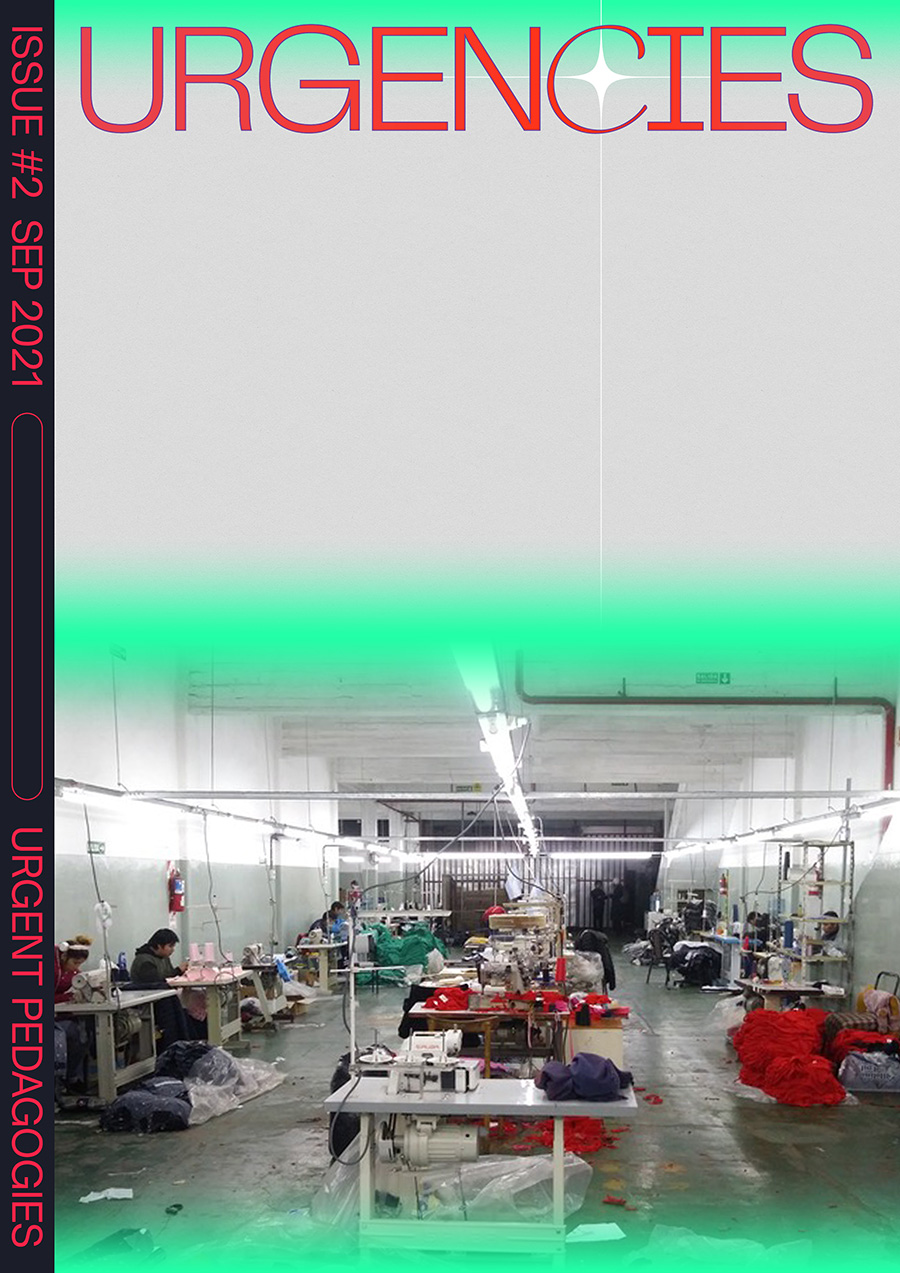

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

This is also the title of bLab*’s book series that starts in October 2021 with our manifesto. The series will be published in German and English and will be edited by Unrast.

is a professor of Pedagogy and Social Work at the Alice Salomon University in Berlin. She holds a double degree in Psychology and Pedagogy and a Ph.D. in Political Science. Her research interests besides Postcolonial Theory lies in Queer Studies, Critical Migration Studies, Critical (Adult-)Education, Conspiracy theories, and Trauma Studies. In 2014 she was a visiting fellow of the Institute for International Law and the Humanities in Melbourne, Australia, in 2015/16 a senior fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) in Vienna and will be the Ustinov-Guest-Professor at the University of Vienna in winter 2021/22. María do Mar Castro Varela is the chair of the Berlin Institute for Contrapunctual Social Analysis (BIKA) and the founder of the bildungsLab* in Berlin.

is a postdoctoral research associate at the Faculty of Education at Bielefeld University. Her research focuses on racism and critical education as well as questions of difference and hegemony. One of the main concerns in her research is the analysis of educational institutions regarding their power structure and exclusionary practices. She also works on postcolonial perspectives and knowledge production. Saphira has been a member of the bildungsLab* since 2017.