Alternative Alliances

Pelin Tan

CATEGORY

“The Urgent Pedagogies project points out such alternative alliances of pedagogies in critical spatial practices. Such practices not only deal with existing structures to transform its power and knowledge production but aim also to invent alliances of methodologies and initiatives.”

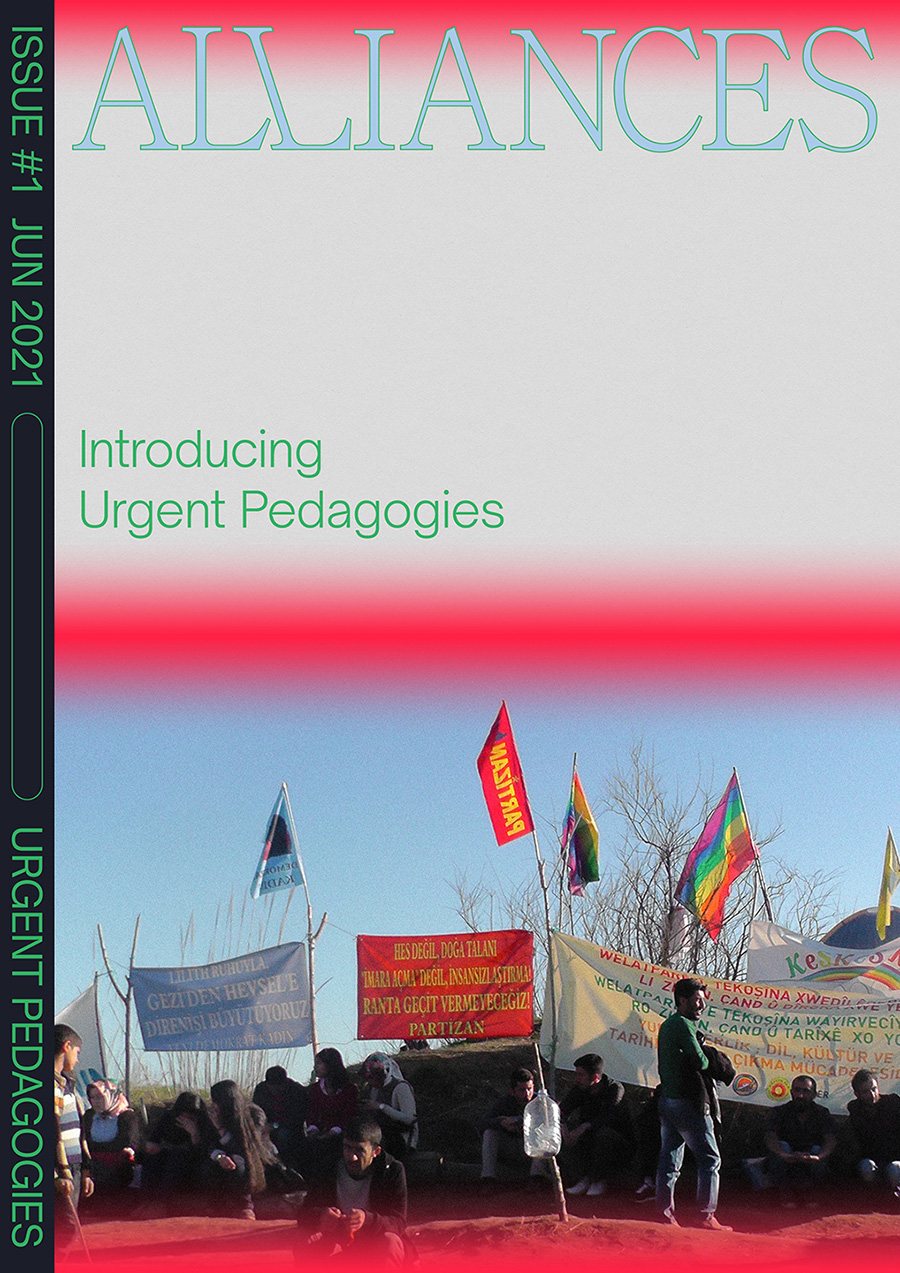

Mardin postgraduate architecture students gathering, Gelîyê Godernê/Lice, Turkey. Photo: David Harvey, 2015

It is more urgent nowadays to create alliances within infrastructures of resistance through our pedagogical practices and research on critical spatial practices. Pedagogy as learning and unlearning structures involves altering methodology, content and tactics that need trans-local territorial (planetary) alliances. The needs and tactics of urgent pedagogies starts from the entanglement of such alliances of solidarity and mutual dependence.

“Alliances” of pedagogical practice is understood neither as permanent nor formal structures by Stuart Hall, who addressed the issue as a decentralization of power and speaking across the differences. Hall was speaking for sure in a certain time and in a certain national condition [1] ; however, his description through his practice and thinking is vital in our current practices of pedagogies in art and architecture, in order to understand the link between pedagogies, knowledge production and its urgency nowadays. As he claims, “teaching” is a cultural practice and is a process of activating knowledge in accordance with the social and political context. Layers of these contexts that are specifically thick with colonial processes, hegemonic institutionalism and extractivist capitalism, prevent the transformation of power of the reproduction of knowledge. Understanding, analysing and producing such socio-politically engaged knowledge through art and architectural pedagogical methodologies lead us to the field of critical spatial practices. As transversal methodologies both from the context of such knowledge production fields and institutional structures, this critical spatial practice allows us to create action research, thus enabling us to practice decolonial processes and be involved with the social space. Creating and being in alliances is part of such a process in critical spatial practices within transversal methodologies that involves many topics of citizenship, militant pedagogy, institutionalism, borders, war, refugeehood, urban/rural, commoning, degrowth and others.

A transversal methodology is often the base of critical spatial practices. It ensures a trans-local, borderless knowledge production that, in a rhizomatic form, reaches beyond such topics of art, architecture and design. Critical spatial practices, almost itself a discipline of study between practice/theory and art/architecture, is based on critical theory of avoiding its dualistic structures. This is described by Jane Rendell as: “… modes of self-reflective artistic and architectural practice which seek to question and to transform the social conditions of the sites into which they intervene”. [2] Rendell acknowledges also intervening into existing institutional structures, and performing/activating them could be also described as critical spatial practices.[3] Transversal practice mainly refers to Félix Guattari’s notion and practice, which he describes as ‘[N]either institutional therapy, nor institutional pedagogy, nor the struggle for social emancipation, but, which invoked an analytic method that could transverse these multiple fields (from which came the concept “transversality”)’ (p.121, Genosko). Meaning, the notion of transversality as a practice in which epistemic and theoretical categories are transverse, and replace each other. It is a practice that is very much embedded, bodily, in everyday life. The ‘institution/instituting’ is part of this, and so creating such a transversal practice also influences the political body of an institution and the way we are instituting. For instance, when I consider myself teaching in art/architecture, particularly as it involves different forms of production and representation of knowledge related both to small-scale design and at the same time larger, different levels of integrated disciplinary knowledge (sociology, sciences, art, etc.), I feel it is a powerful tool that could be taken further with students or participants. Here scale has two dimensions which is firstly the scale of disciplinary enlargement and secondly the physical (spatial) scale. Students’ and participants’ actions are part of this togetherness in the transversality of pedagogy and its affect (capacity of transforming the social). [4] Methodology is also a political tool that takes part in the process of knowledge production (in teaching, learning, unlearning, building up curriculum, syllabus and field research). Thus, the ‘Assemblage Method’, according to John Law (p.122, Law): “is the process of enacting or crafting bundles of ramifying relations that condense presence and (therefore also) generate absence by shaping, mediating and separating these. Often it is about manifesting realities out-there and depictions of those realities in-here. It is also about enacting Othernesses.” The teacher as colonizer in a certain territory is in a problematic position, however assemblage methods can be a means to help create the needed radicalism with the colonized subjectivity -one in which the colonizer identity is not based on fundamental justifications of a politically correct emancipatory act. Following Law’s statement in his (2004) book After Method, which mainly concerns critical approaches to method in the social sciences, can also reveal methodological problems that may contribute to architecture research and its pedagogy. How can we understand the possibilities of creating such transversality that enacts Otherness, as teachers, as pedagogies? The term “affective pedagogy” refers to Deleuzian meditations on Spinoza’s concept of ‘affect/affections’ that is beyond the body, and assemblages of form have been described in a context for new methods in aesthetics: “Affect is a starting place from which we can develop methods that have an awareness of the politics of aesthetics: methods that respond with sensitivity to aesthetic influence on human emotions and understand how they change bodily capacities.” (2013, Hickey-Moody)

The term “decolonization” in education is often used in discussions following the legacies of Franz Fanon and Paulo Freire. This term became important as it signifies not only an institutional criticism but a search for alternative knowledge production beyond the structure of colonizer/colonized. In the context of colonizer/colonized relations and subjectivities, “decolonization” not only means resisting territorial occupation and violence but also transforming institutions, cultural production, approaches and values. Moreover, in the context of pedagogy, “decolonization’”basically signifies a non-institutional education where knowledge is produced and shared collectively. Eve Tuck and Wayne Yang (p.1, Tuck&Yang) argue that “decolonization” is a metaphor: “The easy adoption of decolonizing discourse by educational advocacy and scholarship, evidenced by the increasing number of calls to ‘decolonize our schools’, or use ‘decolonizing methods’, or, ‘decolonize student thinking’, turns decolonization into a metaphor.” The critical stance they elaborate in their article gives a deep insight to help understand why we use this term in the context of pedagogy. They continue: “Decolonization as metaphor allows people to equivocate these contradictory decolonial desires because it turns decolonization into an empty signifier to be filled by any track towards liberation” (p.7, Tuck&Yang). For them, an anti-colonial critique and decolonization are slightly different things. Their critique helps give a better understanding of the term. Yet the dualistic structures of colonizer-oppressed subjectivities are more complex today and are relative from territory to territory. In my opinion, using the word as a metaphor still grants us emancipative power to reconsider our methodologies, the process-based research tools, the complex realities of territories and the actors of the social production of art and architecture.

The university or academia is always considered the primary place for the production and dissemination of knowledge. Alternative initiatives and ways of producing knowledge, such as collective research and its representation via social media, are the main forms of non-institutional structures or “becoming” institutions. Transversality is the practice that cross-creates and disseminates knowledge. The basic principles for a decolonizing educational structure are, first, to construct non-hegemonic knowledge through collective processes, and, second, to create an “instituting practice” without remaining, or never fully reaching, the status of an “institution”. Education is by default a fully instituting structure, where the institution itself becomes a machine that exists for the sake of sustaining itself. It is a form of colonizing pre-existing knowledge of all involved in the process: students and teachers alike. What is a collective process in education? It is the destruction of the hierarchies of dualist structures between teacher and student, teaching and learning. Decolonizing education means collective self-teaching, learning by acting together, rejecting the gap between theory and practice, and deconstructing terms in education that are sustained by the institution, while preserving traditional knowledge from the earth and nature. The methodology, the syllabus and the content of any topic are the basis for a pedagogy.

Today, since the last decade, the gap between theory and practice has been challenged by social scientists who search for methodologies of affective pedagogy and social engagements. As art and architecture education is increasingly influenced by social practice, this affects not only the content but also the pedagogical strategies. Transdisciplinary thinking, new media tools that provide performative visual tools of representation, and engagements as a militant researcher in everyday life in order to experience other “knowledge” or the multiplicity of knowledge production, all urge us to alter our research methods.

Alternative collectively initiated pedagogical platforms and assemblies are emancipative forms of solidarity, care, resistance, and knowledge production. What are the urgencies of art and architecture pedagogies in contested territories? How can pedagogies reveal and bring about ways of unlearning and undoing? Can alternative approaches in education and research reach beyond established institutional structures and through transversal and collective approaches? Do they make a difference in transforming knowledge, and how do they shape art and architecture practices of the present? Pedagogies have the power to design infrastructures that have the capacity in instituting power. Such infrastructures may be defined as infrastructures of resistance that can sustain the curriculum, care, and solidarity through knowledge production. Infrastructures of resistance are referred to in many anarchist pedagogies: “Infrastructures of resistance serve as a means by which people can sustain radical social change before, during, and after insurrectionary periods.” (p.172, Shantz). In this context, that definition is claimed for non-union structures and for multiple social classes. Thus, it can be defined in the frame of critical spatial practices of action research and methodologies in multiple alliances for art and architecture as well.

The Urgent Pedagogies’ project points out such alternative alliances of pedagogies in critical spatial practices. Such practices not only deal with existing structures to transform its power and knowledge production but aim also to invent alliances of methodologies and initiatives. For instance Campus in Camps initiative in Dheisheh Palestinian Refugee Camp in Palestine, is one of the collective unlearning platforms that younger generation inhabitants of the camp, researchers, artists and architects are involved in redefining many common concepts such as commons, ecology, citizenship and curriculum in the action of decolonizing the everyday life conditions of a camp. On the other hand, another example of an initiative is Interflugs, a student collective that acts and reflects within social struggles and movements as an autonomous body inside an institution of the art academy in Berlin. Diverse forms of instituting either in a refugee camp or inside an institution in the heart of Europe provides experiences of instituting and infrastructures that put the possibilities of alliances in our horizon.

Henry Giroux mentions Hall’s legacy on pedagogy: “For Hall, culture provides the constitutive framework for making the pedagogical political – recognizing that how we come to learn and what we learn is imminently tied to strategies of understanding, representation, and disruption.”[5] In conclusion; forming alliances as infrastructures of resistance, trans-territorial solidarities and altering within transversal methodologies are more than ever urgent in pedagogies of art and architecture.

Jeffery Shantz 2012 “Learning to Win: Anarchist Infrastructures of Resistance”, Anarchist Pedagogies (Collective Actions, Theories, And Critical Reflections on Education), Edt.Robert H.Haworth, PM press, Oakland, p.162-174.

Henry A. Giroux 2000 “Public Pedagogy As Cultural Politics: Stuart Hall and The Crisis of Culture”, Culture Studies 14(2), Routledge, p.341-360.

Greig de Peuter 2007 “Universities, Intellectuals, and Multitudes: An Interview with Stuart Hall”, Utopian Pedagogy, University of Toronto Press.

Jane Rendell, 2016 “Critical Spatial Practice as Parrhesia”, MaHKUscript: Journal of Fine Art Research, 1(2): 16, pp. 1–8.Tuck, Eve and Yang, K. Wayne 2012 ‘Decolonization is not a metaphor’, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1(1): 1–40.

G. Genosko (Edt.) 1996 The Guattari Reader, Oxford: Blackwell.

Pelin Tan 2017 “Decolonizing Architectural Education: Towards an Affective Pedagogy”, The Social Re Production of Architecture, Routledge.

Anna Hickey-Moody 2013 “Aesthetics and affective pedagogy”, in Rebecca Coleman and Jessica Ringrose (Eds.) Deleuze and Research Methodologies, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 79–95.

John Law 2004 After Method: Mess in the Social Science Research, London: Routledge.

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

“Universities, Intellectuals, and Multitudes: An Interview with Stuart Hall”, interviewed by Greig de Peuter, Utopian Pedagogy.

2.

Ibid.p.1. “I call ‘critical spatial practice’. In art such work has been variously described as contextual practice, site-specific art and public art; in architecture it has been described as conceptual design and urban intervention. To encounter such modes of practice, in Art and Architecture I visit works produced by galleries that operate ‘outside’ their physical limits, commissioning agencies and independent curators who support and develop ‘site-specific’ work and artists, architects and collaborative groups that produce various kinds of critical projects from performance art to urban design.”

3.

Rendell, J 2016 Critical Spatial Practice as Parrhesia. MaHKUscript: Journal of Fine Art Research, 1(2): 16, pp. 1–8, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/mjfar.13

4.

The understanding of such a methodology is often affiliated with terms in alternative knowledge and pedagogy practice such as ‘assemblage methods’ or ‘affective pedagogy’.

5.

Henry A. Giroux, Public Pedagogy as Cultural Politics: Stuart Hall and The ‘Crisis’ of Culture, Cultural Studies 14(2) 2000, 341–360, Routledge.

is the 6th recipient of the Keith Haring Art and Activism and fellow of Bard College of the Human Rights Program and Center for Curatorial Studies, NY, 2019-2020. She is a sociologist, art historian and currently Professor, Fine Arts Faculty, Batman University, Turkey. Tan is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Arts, Design and Social Research, Boston; and researcher at the Architecture Faculty, University of Thessaly, Volos (2020-2025). She is the co-curator of the Cosmological Gardens project by CAD+SR and she was the curator of the Gardentopia project of Matera ECC 2019. Tan, was a Postdoctoral fellow on Artistic Research at ACT Program, MIT 2011; and a Phd scholar of DAAD Art History, at Humboldt Berlin University, 2006. Her field research was supported by The Japan Foundation, 2011; Hong Kong Design Trust, 2016, CAD+SR 2019. She was a guest professor at Ashkal Alwan, Beirut 2021; Visiting Professor at School of Design, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, 2016 and at the Department of Architecture, University of Cyprus, 2018. Between 2013 and 2017 she was an Associate Professor of the Architecture Faculty at Mardin Artuklu University. She is a member of Imece refugee Solidarity Association and co-founder of Imece Academy; advisor of The Silent University and the pedagogical consortium of Dheisheh Palestinian Refugee Camp, Palestine. In 2008 she was an IASPIS grantholder.