Learnings/Unlearnings: Revealing, Reimagining, Reframing, and Rewriting

Elke Krasny, Marietta Radomska, Nina Bartošová, Burcu Yiğit Turan, Lis-Mari Gurák Hjortfors, Karin Reisinger

CATEGORY

Welcome to Learnings/Unlearnings Reader #6: Revealing, Reimagining, Reframing, and Rewriting, edited by Elke Krasny, Karin Reisinger, and Meike Schalk. The Reader combines contributions from the section “Environmental Learning Discourses,” including Elke Krasny’s keynote lecture, essays by Marietta Radomska, Nina Bartošová, and Burcu Yiğit Turan, and a workshop by Lis-Mari Gurák Hjortfors and Karin Reisinger. They were presented at the conference Learnings/Unlearnings: Environmental Pedagogies, Play, Policies, and Spatial Design, which took place in Stockholm in September 2024.

To ground and support environmental learning, Reader #6 gathers a variety of important questions that emerged from conversations and encounters in pedagogical work. How can we learn from environments to overcome the split between humans and ‘nature?’ How can we re-imagine grieving, yet also take care of what remains? How can we work together across disciplines, species, ethnicities, and different regions, and engage in the decolonisation of environments and theories? The authors share discourses and their approaches to these inquiries, from their multiple experiences of working with the environment, facing challenges, complexities, and ruptures.

The contributions in this Reader offer a variety of approaches, concepts, and experiences. They give an account of, and reflect upon, pedagogical encounters via specific toolboxes, or instructions, that support the revealing, reimagining, reframing, and rewriting of complex engagements.

In her contribution “Pedagogies of Care: Air, Water, and Soil,” Elke Krasny foregrounds the importance of a “we,” a plurality, as a way of thinking with many others. Krasny uses the word “we” to open up perspectives of care as solidarity, interdependency, and intervulnerability of humans and environments. She asks how are we being taught to view care as exploited, invisible, and silenced? How can we begin to learn together with many others to imagine care otherwise? These questions are central to thinking about pedagogies of care, and her text shares three “lessons” of air, water and soil through which one can start to read care, showing how these elements are essential to notions of care and, at the same time, in need of care to inspire collective learnings.

In “‘What Remains’: Un/Learning How to Grieve, Re/Imagining How to Care,” Marietta Radomska reminds us that learning always entails some un-learning, and imagining involves some re-imagining. Focusing on the ongoing ecocide unleashed through Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, unfolding since February 2022, Radomska asks about possibilities not only to learn how to grieve, but also how to mobilise an ethical response and concern. Radomska shows ways in which ecological grief, socio-cultural and artistic imaginaries of crisis, and environmental ethics become interwoven in art, artivist, and community projects engaging with environmental violence and death. She suggests that affective engagements with art assist us in experiencing and comprehending the more-than-human loss and eco-grief, and by doing so, oblige us not only to witness, but also to care.

Nina Bartošová demonstrates in her “Workshop on the Brno-Cejl area: experiencing space and its conceptualization through a writing process” how architecture students experience new ways of approaching historically complex and stigmatised sites, by teaching and learning through an instructed writing course. Bartošová’s example is Cejl Street in Brno, Czech Republic, which is inhabited predominantly by the Roma minority, however the neighbourhood is experiencing emerging gentrification. Bartošová argues that it is possible to cultivate architecture students’ ability to identify design problems in the environment they engage with outside the design studio by providing them with a process that allows for experiencing environments with complicated layered histories, thus giving students the opportunity to develop their own critical thinking.

In “Double Consciousness Towards a Decolonial Critical Theory, History, and Practice of Landscape Architecture” Burcu Yiğit Turan offers the theory of double consciousness as a framework to critically examine coloniality and Whiteness in spatial and environmental epistemologies. Turan argues that our understanding of histories, theories, and practices are disconnected from challenging knowledges that give an account of the broader context of the modern/colonial world system, which encompasses the colonial and racial dynamics of capitalist land accumulation, resource appropriation, and labour exploitation at a planetary scale. She argues for an education that cultivates consciousness in the fields of planning and architecture. Revising histories, theories, and practices can help us build solidarities across various geographies—transnational, national, or local—and guide us in “imagining and building democratic, just, and non-imperial/colonial societies.”

Lis-Mari Gurák Hjortfors and Karin Reisinger, in “Decolonizing the Mining Landscape” give an account of their workshop, which collected potential spatial practices for the decolonisation of a mining area in Sápmi, in Northern Sweden. Participants were asked how they can support the Indigenous decolonial struggle against extractivism with their practice? The workshop “Spatial Practices of Decolonizing the Mining Landscape” developed from a conversation about the absence of Sámi narratives in local urgent heritage practices, and is the first collaboration of the local Sámi ethnologist Lis-Mari Gurák Hjortfors, and architect and researcher Karin Reisinger, after eight years of continuous exchange. In this essay they show how they relate and complement their spatial and pedagogical practices, and invite audiences into this process, stressing that across countries, contexts, languages, and formats, and between research and cultural production, the hard task of decolonisation needs multiple voices and approaches. It requires not only multiple formats, but also needs to transgress the multi-layered compartmentation of cultural production and knowledge dissemination with these formats to come together in the shared aim of decolonisation—of an area but also of our disciplines and our practices.

Contents

Pedagogies of Care: Air, Water, and Soil

Elke Krasny

Care is essential. Care is ubiquitous. Care is exploited. Care is invisible. Care is silenced. Thinking about the afterlife of the long histories of capitalist colonial patriarchal modernity that have resulted in these specific cultural, economic, and social conditions of care, leads us to ask the following questions. How are we being taught to view care as described above, exploited, invisible, silenced? How can we begin to learn together with many others to imagine care otherwise? These questions are central to thinking about pedagogies of care. Classrooms for learning what care is and what care does are essential. Such classrooms could be everywhere, they are not confined to the indoors. Rather, we hold that the outdoors may provide us with much better classrooms for practicing pedagogies of care.

Before going into more detail what we mean by pedagogies of care and how these can be practiced, we want to use the space of this paragraph to explain the use of the personal pronoun we in this text. The use of this pronoun in this text is deliberately ambiguous. This personal pronoun, we, has in the recent past, which is marked by rapid capitalist expansion, rampant, extraction, neo-colonialism, neo-authoritarianism, far right ideologies, and compulsory competition, become the territory of contention and division. The pronoun we is characterized by a politics of fierce fighting that often leads to conversations and debates coming to an end. This is one of the reasons why this text works with a quite oscillating use of the pronoun we, which includes the following uses. The term we is also being used to refer to a condition considered as globally produced and thus widely generalizable, even though, of course, always locally specific and situated. The pronoun is also used to refer to the author, who has written this text. The author likes the idea of we, the pluralis modestiae, the plural of modesty, instead of I, first-person singular. Writing in the first-person plural acknowledges, at the level of grammar, that plurality is a way of thinking with many others, on whose thoughts we draw, with whose thoughts our thoughts are deeply entangled, and, more than anything, to whose thoughts and insights we are deeply thankful. And, the author aims to acknowledge through the use of first-person plural that our physical selves, the bodies we inhabit as humans are never one, but always plural, home to a very diverse community of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and archaea. At the cellular level, there are more bacterial cells than human cells in human bodies. And, our bodies’ systems, respiratory, digestive, and circulatory, are passage to the environment: air, soil, water, all in their anthropogenic state of industrialized capitalist transformation, move through and with our bodies. We is used to speak to a politics of solidarity and to an ethics of humbleness that extends beyond the human as autonomous or individual. Precisely because of the fact that the environment moves through human bodies and that human bodies are more non-human than human at the cellular level calls for solidarity and humbleness. Hence, we use the word we to open up perspectives of care that see care as solidarity with the interdependency between environments and humans. “Interdependency is not a contract, nor a moral ideal—it is a condition.” (Puig de la Bellacasa 2017, 70) The same holds true for intervulnerability. Intervulnerability is neither a contractual nor a moral relationship, but a condition. Starting from interdependency and intervulnerability and interdependency views care as solidarity with the planet as a whole. In order to learn how to practice care as solidarity it is relevant to understand how care has been silenced. Not only the histories of classed, feminized, and racialized exploitation and invisibilization have led to a silencing of care, also the histories of how species other than the human species, how environments, how the planet as a whole is part of the condition of interdependency and intervulnerability and, at the same time, part of the histories of carelessness or care as solidarity, if we choose to change the course of history into the direction of care as solidarity.

This text does not posit that care be viewed as yet another specialized, and separate field of studies. That is, we are not necessarily arguing here for the establishment of care studies with undergraduate and graduate degrees and universities producing care scholars and care experts, even though we do see the attraction or potential of such care studies. Here we think about pedagogies of care as relevant to all fields of studies and disciplines with care not a separate thing, not an expert thing, not something separate from all other studies and knowledges in their plurality. Different study programs such as for example architecture, design, landscape, and urbanism would imagine and put into practice pedagogies of care most relevant to the concerns and pressing matters of their field. This said, we can still imagine there to be overarching critical questions connected to care, which are of relevance to and can productively be shared by many different fields of studies and disciplines.

This text shares three ‘lessons,’ which we could also understand as ‘exercises’ or ‘readings.’ The use of lesson, exercise, reading is deliberate. It makes use of the vocabulary through which practices of teaching, that is pedagogy, are structured. The aim is to demonstrate how by working with existing texts we can turn a specific paragraph into a passage taking us to complex questions relevant to pedagogies of care. The interest here is on sharing lessons of care with a specific focus on how what is commonly called the environment is not only around us, not only surrounding human beings, but deeply inside of us and shared with many others by the environment’s passage through human bodies. The following three lessons are dedicated to air, water, and soil. Or, put differently, air, water, and soil are the teachers of care.

Take a deep breath. With every inhalation, industrially produced molecules are drawn into your being. Once inhaled, synthetic molecules may pass through membranes, connect with receptors, nestle in fatty tissue, mimic a hormone, or modulate gene expression, thereby stimulating a cascade of further metabolic actions. Breathe in. We cannot help it. You must breathe to live, like you must drink and eat. There is no choice in the matter. It is a condition of our being. With each breath we are recommitting to an ongoing relationship to building materials, consumer products, oil spills, agricultural pesticides, factories near and far that all contribute to the emission of these synthetic molecules. (Murphy, 2016. 1)

Michelle Murphy, scholar of technoscience with a focus on the recent past and on environmental justice, shows that bodily, environmental, and chemical interdependencies are part of the relations of care. Using Murphy’s reflections leads to the following questions useful to working with air in pedagogies of care: How do we relate care to air? How do we understand that pollution is carelessness? How do we connect our breath to the histories of anthropogenic ruination of the atmosphere? How can we learn together that we are breathing and circulating the air of capitalism?

Air is fundamental to care and care is fundamental to air.

Monolithic megadams displace humans and other animals to radically reshape riparian ecosystems. New islands of plastic rise out of the sea, while old caches of chemical warfare agents lie patiently beneath, slowly releasing distant memories. Understanding how water has reached this state of degradation and exploitation asks us to carefully consider our own implications within this hydrocommons – in terms of not only what we do ‘to’ water but as water bodies ourselves. (Neimanis 2017, 104)

Cultural theorist Astrida Neimanis, who brings together feminist philosophy and the environmental humanities, invites us to think about human bodies as water bodies among other water bodies. Water in pedagogies of care can be approached through the following questions: How do we relate care to water? How do we study both extraction and construction as forms of carelessness? How do we connect the water inside of our bodies with the water outside of our bodies? How do we begin to feel and know that the water inside of our bodies is the water outside of our bodies? How can we learn together that we are drinking, swallowing, and bathing in the water of capitalism?

Water is fundamental to care and care is fundamental to water.

Soil is a multifaceted material archive which does not fit within any single discipline: It contains bodies of plants, animals, humans, sedimentation and ancient rock and also remnants of human endeavour; ancient artefacts, lead, mercury, microplastics, arsenic, petrochemical run off, benzene. […] Soil is both the habitat and organisms that inhabit that habitat […] The link between bodies and soil can also be between life and death. While alive, the immune system resists bacteria, fungus and viruses just enough to hold the body together. When we die and the immune system stops mediating, we rapidly are overrun and metabolised, we become soil and (if given the opportunity) return to the earth. We are constituted by soil (it grows the food we eat) and we are the soil of the future. (Robertson. 2024, 99-102)

Artist and researcher Kari Robertson, who focuses on eco-social themes, encourages us to reflect on soil and bodies as deeply connected material archives, which are teeming with the aliveness of a multiplicity of organisms. Soil in pedagogies of care can be approached through the following questions: How do we study the human body as a material archive of soil tracing the foods we digest, and absorb food? How do we imagine our lips touching the soil, where the food comes from, when we ingest it, that is, when we put it into our mouth? How do we study overuse and exhaustion of soil as industrialized carelessness? How can we learn together that our bodies are part of the soil of capitalism?

Soil is fundamental to care and care is fundamental to soil.

The three lessons, in which we turned to air, water, and soil as teachers for pedagogies of care, turned to the work of theorists Michelle Murphy, Astrida Neimanis, and Kari Robertson, who are working across ecologies of the social and the environmental. Using citations from their writings served to open up questions how air, water, and soil are essential to care and, at the same time, in need of care. These questions are offered here as inspirations for all kinds of classrooms that are in and with the air, the water and the soil. The hope is to inspire collective learnings in the search for answers and, of course, always also more questions. Central to pedagogies of care is to overcome the capitalist colonial patriarchal split between human beings and environments. This specific modern subject that was not only seen as independent from nature, and thus the environment, but also as dominator over the environment, was named by Anna Tsing as “Enlightenment Man”. (Tsing 2016, 3) Overcoming the effects of the Enlightenment Man and inhabiting the realities created in His afterlife, requires from us to learn that human beings and their environments are inseparable from each other. This inseparability, which includes interdependency and intervulnerability, is the condition from which pedagogies of care start out. Building on, yet going beyond the definition of Joan Tronto and Berenice Fisher, that “caring be viewed as a species activity” we hold that caring be viewed as a multi-species activity. (Tronto and Fisher 1990, 40) The ‘we’ that can live in the world as well as possible then becomes a much more expansive we including the planet in its entirety.

Pedagogies of care are working for a politics of solidarity that not only acknowledge the inseparability of human beings and environments, but aims to understand what these most intimate entanglements mean for caring otherwise, when animals, bacteria, fungi, humans, metals, minerals, mycelia, rocks, viruses, and, ultimately the planet as a whole are understood as teaching and learning with each other what pedagogies of care are.

References

Murphy, Michelle. 2016. “What Can’t a Body Do?” Catalyst. Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 31, no.1: 1-15. Accessed November 27, 2025, at https://catalystjournal.org/index.php/catalyst/article/view/28791/pdf_5.

Neimanis, Astrida. 2017. Bodies of Water. Posthumanist Feminist Phenomenology. London: Bloomsbury.

Puig de la Bellacasa, María. 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. Minneapolis, MI and London: University of Minnesota Press.

Robertson, Kari. 2024. “Gravity, Immunity, and Soil”, in Promiscuous Infrastructures. practicing care, edited by Michelle Teran, Marc Herbst, Vivian Sky Rehberg, Renée Turner and The Promiscuous Care Study Group, 96-103. Leipzig: Journal for Aesthetics & Protest, Rotterdam: WdKA Research Center.

Tronto, Joan C., and Fisher, Berenice. 1990. “Toward a Feminist Theory of Caring.” In Circles of Care: Work and Identity in Women’s Lives, edited by Emily K. Abel and Margaret K. Nelson, 36-54. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1990.

Tsing, Anna. 2016. “Earth Stalked by Man,” The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 34.1: 2-16.

’What Remains’: Un/Learning How to Grieve, Re/Imagining How to Care

Marietta Radomska

At the time of planetary more-than-human polycrisis, where staying hopeful turns into a gargantuan task, learning how to be with, for, and of the environment(s) we are entangled in, is of vital importance. Learning, however, always entails some un-learning; and imagining involves some re-imagining. One may ask: what remains? And consequently, what is to be done?

In the present essay, I pose these questions while focusing on environmental violence; a type of violence that unravels through entangled mechanisms comprised of soft and hard technologies that pierce through more-than-human bodies at diverse speeds, to various extents, and at different spatio-temporal scales. Its workings may be ‘slow,’ occurring ‘gradually and out of sight’ (Nixon 2011, 2), like eighty-year-old bombs at the bottom of the Baltic Sea. But they may also be ‘abrupt’ (Neimanis 2021), like the bombings of animal shelters, national parks, or nature reserves since 2022 by Russians on the Ukrainian soil (BlueCross 2023). One particular form of environmental violence is ecocide—in its ‘everyday’ sense, as a scientific term, and as a legal category. Simultaneously, a sense of grief becomes increasingly tangible in contexts where planetary environmental disruption transforms habitats into unliveable spaces and induces socio-economic inequalities and shared more-than-human vulnerabilities (Pevere 2023; Geerts and Carstens 2024). Such grief stands out even more when ecocidal violence and immediate destruction are at stake.

In what follows, I focus on the ways in which ecological grief, socio-cultural and artistic imaginaries of crisis, and environmental ethics become interwoven in art, artivist, and community projects engaging with environmental violence, ecocide, more-than-human vulnerability, death, and loss. I discuss two such initiatives created as a response to the ongoing ecocide unleashed through Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, unfolding since February 2022. These projects engage in the individual and collective processes of un/learning how to cope with the loss and rupture, how to grieve, and also, how to mobilise an ethical response and concern. They activate a unique opportunity of environmental learning – a poignant, affective, and necessary gesture of radical re/imagining of how to care.

Environmental violence also has a different side: the despair, grief, frustration, and anger of conservationists whose work is being lost or rendered impossible, the locals whose home landscape is being destroyed, and plainly, the bystanders aware that some species and populations may never return to a given site or might be lost forever. Environmental humanities scholar and artistic researcher Darya Tsymbalyuk asks: ‘What does it mean to research environments when entire ecosystems are being erased?’ (2022a). These affects become implicitly or explicitly woven in the expressions of researchers working with the injured landscape. What protrudes in their testimonies and writings are the ever-present traces of eco-grief (Stone 2024; Dovzhyk 2023). Yet, these traces unfold into creative literary and visual storytelling practices, reaching out beyond academia and demanding an ethical response.

The notion of eco-grief describes experiences of grief occurring in relation to the present or anticipated ecological losses of species, ecosystems, and landscapes, resulting from severe anthropogenic environmental change (Cunsolo and Landman 2017). Eco-grief scholarship has its firm grounding in anticolonial, Indigenous, and environmental humanities perspectives. Focusing on the relation between eco-grief and extinction, environmental humanities scholars Owain Jones, Kate Rigby, and Linda Williams write: ‘biological and cultural extinction goes hand in hand with the extinction of hope: the hope of recovery, of reflourishing (genetic resurrection or cultural reconstruction notwithstanding)’ (2020, 393).

Scholars investigating the consequences of climate change, settler colonial violence, and extractivism, emphasise the importance of discussing questions of eco-grief experienced by Indigenous Peoples and First Nations in different parts of the world. A significant amount of situated eco-grief research focuses on the problematic of eco-mourning in the context of the lands forming part of Canada, Australia, or South-East Asia (e.g. Cunsolo and Landman 2017; Chao 2022). These key works not only expose the social, cultural, ethical, and philosophical dimensions and meanings of eco-grief, but also shed light on its transformative, political, and activating potential.

However, less is being written on the experience of ecological loss in places that tend to escape the attention of international scholarship: the wounded landscapes of semi-peripheries (cf Nikolić 2025). In her artistic and academic work, Tsymbalyuk (e.g. 2025) gives a testimony to the multi-level workings of environmental violence and the accompanying experiences of grief, loss, and erasure. Materially and/or affectively, violence cuts into the flesh of humans and their more-than-human environments. Tsymbalyuk care-fully captures these mechanisms in the following way:

There is a myriad of deaths in the Ukrainian woods these days. There is a dying of more-than-human worlds, of biotopes, of relations that form them, and of inhabitants that populate ecosystems. Many of these deaths hardly make the news. Most are not registered, and cannot be registered as we cannot access the places and as more-than-human deaths are not counted. Many deaths are yet to come even after the end of the war, when another land mine detonates somewhere deep in the woods (…). [T]he war exacerbates the rupture of relations, cutting right through more-than-human worlds. (Tsymbalyuk. 2022)

In Tsymbalyuk’s work, textual and visual storytelling takes the lead: creative practice and expression powerfully shed light on experiences of eco-grief and particular situated ways of working with—and not against—it.

What comes forward in this context is art’s and creative practices’ unique potential for attending to the sensorial, the experiential, and the ethical; for creating knowledge in ways that ‘touch’ beyond the borders of the academia, and that mobilise a personal ‘commitment.’ Some of contemporary artworks transform cultural understandings, significance, and meaning of death and grief. They question conventional frames of human exceptionalism, typically employed in philosophical discussions on death; they shed light on the relational, ecological ontology of death; and they open up an ethical enquiry (Radomska 2023). In other words, art often captures the uncapturable; it intimately mobilises questions, problems, and ethical responses.

One such example is Ukrainian artist Polina Choni’s project Black Soil (2023), developed during her residency at AARK, Finland. Black Soil consists of a series of mixed-media sculptures and images. But the primary medium is bread: ‘fragile, temporary, sensual material, similar to the human body or life itself’ (Choni 2023). Bread in Choni’s works becomes a space where cultural and symbolic values and heritage intersect with questions of temporality, history—including the scar of the Holodomor, the Stalin-engineered famine which killed over five million inhabitants of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in the 1930s (Appelbaum 2017)—ongoing war, and the unfolding ecocide with its more-than-human scales. The bread dough, shaped into traditional symbolic motifs, is used to create sculptures: bread masks, a tree with birds sitting on its branches, and wheat ears attached to a piece of charred wood. Some of the components are burned and covered with ash: the birds and the wheat, painfully referring to the destruction and death brought by Russian shelling. One of the bread masks is placed in a box of soil, with grass pushing up through an empty eye socket. The artwork clearly recalls the uncountable dead, both human and nonhuman—some named, most never recognised—laid in the earth, forever. The contrast between the softness, nourishment, and warmth we tend to associate with the bread itself, and the story of violence, death, and destruction presented in Black Soil leaves the audience deeply moved by how poignant, yet accurate, this visual narrative is.

Fig. 1: Black Soil (2023), by Polina Choni. Photo: Polina Choni. Courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 2: Black Soil (2023), by Polina Choni. Photo: Johanna Naukkarinen. Courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 3: Black Soil (2023), by Polina Choni. Photo: Johanna Naukkarinen. Courtesy of the artist.

In Choni’s art, cultural history, memory, traditions, and material traces become interwoven with vulnerability, ephemerality, care, and intimate rituals of grieving the more-than-human, or life itself, presently exposed to murderous violence. Her artworks provide a poetic and ethical visual landscape of remembering, feeling, hoping, and mourning (Choni and Radomska 2025).

Another form of remembering and reimagining can be found in Tsymbalyuk’s multi-modal storytelling projects, like I dream of seeing the steppe again (2022-23, and its three editions: in London, Edinburgh, and Tbilisi), where she invited audience members to ‘learn about different species and draw a plant on a shared piece of paper, hoping to collectively imagine the steppe in bloom’ (Tsymbalyuk n.d.). The drawings and stories unfolded from the engagement with the photo archive created by Serhii Lymanskyi, the director of Kreidova Flora (Chalk Flora), a nature reserve in Donetsk Oblast and a dwelling for many endangered species, presently exposed to heavy fighting.

Each of these modes of creating knowledge and engaging with questions of environmental violence activates a different kind of space: a space of reflection, of weaving complex enfleshed and continuously unfolding ethical relations to the altered – maimed, poisoned, destroyed, or killed – landscapes, ecosystems, species, and individual animals, plants, or places, remembered by a given individual or community. In these creative engagements, feelings of grief and mourning are woven through the tissues of words and materials. They sensitise the audience to the suffering, death, and loss typically marginalised, insufficiently paid attention to, or not counted at all.

Writers and artists do intervene into worldviews, individual and shared affects, horizons of thinking, feeling, and imagining. These interventions touch on shared – human and nonhuman – vulnerability. The stories of spaces and their more-than-human inhabitants – maimed by environmental violence – come to light through the textures of scholarly, literary, and poetic writings and artworks. Moreover, it is no longer human exclusively who is mourned and worth of concern and care (cf Lykke, Mehrabi, and Radomska 2025). Remembering and grief take various shapes. Affective engagements with art assist us in experiencing and comprehending the more-than-human loss and eco-grief, and by doing so, they oblige us not only to witness, but also to care.

This work was supported by FORMAS – A Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development [grant number 2022-01728].

The argument presented in this essay draws on my research published in 2024 in the journal Somatechnics (Radomska 2024).

References

Appelbaum, Anne. 2017. Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine, London: Penguin.

BlueCross. 2023. “Shelter bombing left dog’s soul crushed.” https://www.bluecross.org.uk/story/shelter-bombing-left-dogs-soul-crushed

Chao, Sophie. 2022. In the Shadow of Palms: More-Than-Human Becomings in West Papua. Durham: Duke University Press.

Choni, Polina. 2023. “The Story Is Not About Bread.” AARK.FI. https://aark.fi/the-story-is-not-about-bread-polina-choni/

Choni, Polina, and Marietta Radomska. 2025. “Ecocide, Ecological Grief, and the Power of Telling Stories: A Conversation”. In Routledge International Handbook of Queer Death Studies, edited by Nina Lykke, Tara Mehrabi, and Marietta Radomska, 205-213. London: Routledge. DOI: 10.4324/9781003398486-19

Cunsolo, Ashlee and Karen Landman, eds. 2017. Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss and Grief, Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Dovzhyk, Sasha. 2023. Ukrainian Lab: Global Security, Environment, and Disinformation Through the Prism of Ukraine. Stuttgart: Ibidem-Verlag.

Geerts, Evelien, and Delphi Carstens. 2024. “Mimetic Resentment’s Violent Somatechnics in Permacrisis Times: Critical Cartographical Contours and Coordinates.” Somatechnics 14(2): 139-161. https://doi.org/10.3366/soma.2024.0430

Jones, Owain, Kate Rigby, and Linda Williams. 2020. “Everyday Ecocide, Toxic Dwelling, and the Inability to Mourn: A Response to Geographies of Extinction,” Environmental Humanities 12(1): 388–405. 10.1215/22011919-8142418.

Lykke, Nina, Tara Mehrabi, and Marietta Radomska. 2025. “Queer Death Studies: In Times of Anthropocene Necropolitics and the Search for New Ethico-Political Imaginations”. In Routledge International Handbook of Queer Death Studies, edited by Nina Lykke, Tara Mehrabi, and Marietta Radomska, 1-25. London: Routledge. DOI: 10.4324/9781003398486-1

Neimanis, Astrida. 2021. “The Chemists’ War in Sydney’s Seas: Water, Time and Everyday Militarisms”, Environmental Planning E: Nature and Space, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 337–353. 10.1177/2514848620904276.

Nikolić, Mirko. 2025. To friends, upstream and downstream, downwind and upwind. Linköping: Linköping University Press. DOI: 10.3384/9789180757546

Nixon, Rob. 2011. Slow Violence: Environmentalism of the Poor, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Pevere, Margherita. 2023. Arts of Vulnerability: Queering Leaks in Artistic Research and Bioart. Helsinki: Aalto ARTS Books.

Radomska, Marietta. 2023. “Ecologies of Death, Ecologies of Mourning: A Biophilosophy of Non/Living Arts.” Research in Arts and Education 2023 (2): 7–20. 10.54916/rae.127532.

Radomska, Marietta. 2024. “Mourning the More-Than-Human: Somatechnics of Environmental Violence, Ethical Imaginaries, and Arts of Eco-Grief.” Somatechnics 14(2): 199-223. https://doi.org/10.3366/soma.2024.0433

Stone, Richard. 2024. “LAID TO WASTE: Ukrainian Scientists Are Tallying the Grave Environmental Consequences of the Kakhovka Dam Disaster.” Science 383(6678): 18–23. https://www.science.org/content/article/ukrainian-scientists-tally-grave-environmental-consequences-kakhovka-dam-disaster

Tsymbalyuk, Darya. 2022a. “What Does It Mean to Study Environments in Ukraine Now?” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia 12, Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. 10.5282/rcc/9494.

Tsymbalyuk, Darya. 2025. Ecocide in Ukraine: The Environmental Cost of Russia’s War. Cambridge: Polity.

Tsymbalyuk, Darya. N.d. “i dream of seeing the steppe again”. Darya Tsymbalyuk’s Personal Website. https://daryatsymbalyuk.com/i-dream-of-seeing-the-steppe-again

Workshop on the Brno-Cejl Area: Experiencing Space and its Conceptualization through a Writing Process

Nina Bartošová

Fig. 1: Workshop participants at the intersection of Bratislavská and Hvězdová streets which the Brnox project led by the artist Kateřina Šedá transformed from a parking lot into a public space, although it did not officially become a square. In the foreground, one can see the concrete armchairs that were created as part of the Brnox project. Photo by Nina Bartošová.

While designing a writing workshop for architecture students, which took place in June 2024 at the Faculty of Architecture of the Brno University of Technology, together with Professor Natalia Ilyin, from Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle – coming to the Czech Republic as a Fulbright Specialist – our goal was not only to strengthen the participants’ ability to justify their designs, but also to make them aware of how they think, and how important it is to consider the relevance of various factors before they begin designing, and even question what seems obvious. We chose a method combining writing in phases with experiencing, with the aim of first identifying and then discussing the potential problem in the selected area. The stigmatized area around Cejl Street in Brno—in close proximity to the city centre—inhabited predominantly by the Roma minority, seemed like a suitable topic for the workshop precisely because of its complexity without obvious solutions, its layered history, and the emerging gentrification. This text argues that it is possible to cultivate architecture students’ ability to identify design problems in the environment they engage with outside the design studio by providing them with both a complex topic and a process that allows them to sufficiently experience not only the environment but also their own thinking.

The chosen area referred here by its historical name Cejl—which has remained in colloquial use—is located between Francouzská, Bratislavská, and Cejl streets in the Zábrdovice district of Brno, right on the edge of the city centre. The name comes from the German word “Zeile” (row), by the appearance of the former independent village, whose buildings were lined up along the main road from Brno to Zábrdovice (Flodrová 2025). Locals call the area also by a number of other different names, including several politically incorrect ones such as “Bronx” or Cigánov (from “cigán” meaning “gypsy”), to indicate the presence of the Roma population, which still makes up the majority of the residents. The term Moravian Manchester, on the other hand, reminds of the fact that since the 18th century (the Austro-Hungarian period), the textile industry was concentrated here, mainly in the hands of Jewish and German manufacturers. Although buildings from this period still predominate here, there were fundamental ethnic changes throughout the 20th century. During World War II, Jews were forced to leave, followed by Germans after the war, while Cejl is associated also with the Holocaust, as it served as a collection point for Jews and Roma before their transport to the Nazi camp in Terezín. Most of present-day Roma inhabitants came originally from Slovak settlements, who were brought here as a labour force during the post-war reindustrialization of Czechoslovakia. (Kuča 2000, 317-323; Sidiropulu Janků 2013, 58). The inhabitants of Brno belonging to the majority tend to still avoid Cejl despite its proximity to the city centre, and often reinforce its negative reputation without ever actually visiting it.

The choice of topic, which was selected in consultation with sociologist Barbora Vacková from Masaryk University in Brno—with whom I already collaborate, teaching architecture students to develop research skills through an observation of a selected place—perfectly met the requirements of the workshop, even though Cejl was not the reason for its initiation. The first idea came from the need to practice writing academic essays as a tool for deepening critical thinking and argumentation, the ability to explain one’s creative process and what it is based on—skills that are not sufficiently addressed in existing courses. Even in design studios, there is not always enough space for the phase of asking questions and discovering design problems, though it is so important for the creative process (Getzels and Csikszentmihalyi 1976, 127-128). The tendency of architects to stick with the first version of a design even if it does not work well (Rowe 1991, 36) also indicates a common reluctance to reevaluate the starting points. While an architect’s proposal does not always respond to a problem in the environment, and architecture is not necessarily about solving problems, a good design needs a directive, a theme, a choice that must be defined by the architect himself/herself. The word “problem” as it is used in this text is therefore not identical to that contained in the school project assignment or that of the client.

We deliberately chose an assignment whose output was not to be an architectural design, but rather what precedes it. Since these were architecture students, we preferred that they acquire knowledge mainly through personal experience of the place, its observation, and less through the study of published sources. In addition to the aforementioned history of Cejl, that already offered some material, workshop participants had the opportunity to also adopt a position towards the project by Czech artist Kateřina Šedá entitled BRNOX (a play on words from Brno’s Bronx, the colloquial name mentioned above), which on the one hand attracted media interest in the area and earned the artist an award for her book of the same title (Šedá, 2016), but at the same time prompted criticism accusing Šedá of caricaturing the residents through her interpretation. Workshop participants were able to experience first-hand the second phase of the project, which consisted of low-budget interventions that are still physically present on site in the form of armchairs made out from concrete (Fig. 1) or murals that raise questions about how the Roma population feels about them. Their current condition, which already bears some traces of time, makes us think even more when we look at the new apartment buildings that have appeared here in recent years. Most of them are designed to seemingly protect and isolate new residents from existing ones, with only a narrow entrance and a garage driveway, not communicating with the street.

From our first online meeting in the fall of 2022—when we began preparing the project in response to a call from the Czech Fulbright Commission—Professor Ilyin demonstrated that she has a lot of valuable experience with writing workshops for students in creative disciplines. I already knew she was an expert on the subject thanks to her book Writing for the Design Mind (Ilyin 2019), which I had used in several of the courses I teach. The book explains in a very clear and illustrative way the importance of academic writing for disciplines that are accustomed to drawing or building models, but less so to writing. The comprehensibility of the text is supported by simple but effective diagrams explaining the structure of an argument and supporting the idea that writing is not necessarily about literary talent but about the ability to think, and above all about patience with multiple rewritings of what has already been written, until one achieves the final form.

The 5-day intensive writing workshop, which was open not only to architecture students but also to students of related fields at schools in the Czech Republic, was ultimately attended only by architecture students. The relatively small group size consisting of seven women and men from 1st year Bachelor’s to PhD proved to be an asset that contributed to an atmosphere of trust that facilitated a good flow of the writing process. A starting point was provided by the first task, where participants were asked to formulate their pre-understanding of the place in order to follow the transformation of their own perspective. Only after the task had been processed in writing did the first visit to Cejl take place. It was left entirely up to the participants to decide how they would grasp the essay, and what they would like to focus on regarding Cejl. Since we expected workshop participants to repeatedly test their ideas directly in the environment and carefully record what they saw and experienced, Cejl’s proximity to the Faculty of Architecture—only a 15-minute tram ride away—was a great advantage, allowing for an optimal alternation of workshop activities, some of which took place in Cejl and some at the faculty.

The entire process was led by Professor Ilyin, who assigned individual tasks on an ongoing basis so that participants could focus on the process itself and not feel overwhelmed. During their first visit to the site, they were asked to observe with an open mind and note down anything they saw that could represent a topic worth exploring in more detail. Back at the Faculty, Ilyin asked the participants to identify key aspects of the preconception about the area and formulate a question that related to one of the aspects of the preconception. The answer to this question was to become the thesis statement. Individual participants shared and discussed their insights. They were then given an hour to elaborate on the thesis in a way that incorporated the preconception and the “researched truth,” i.e. what they observed on the site.

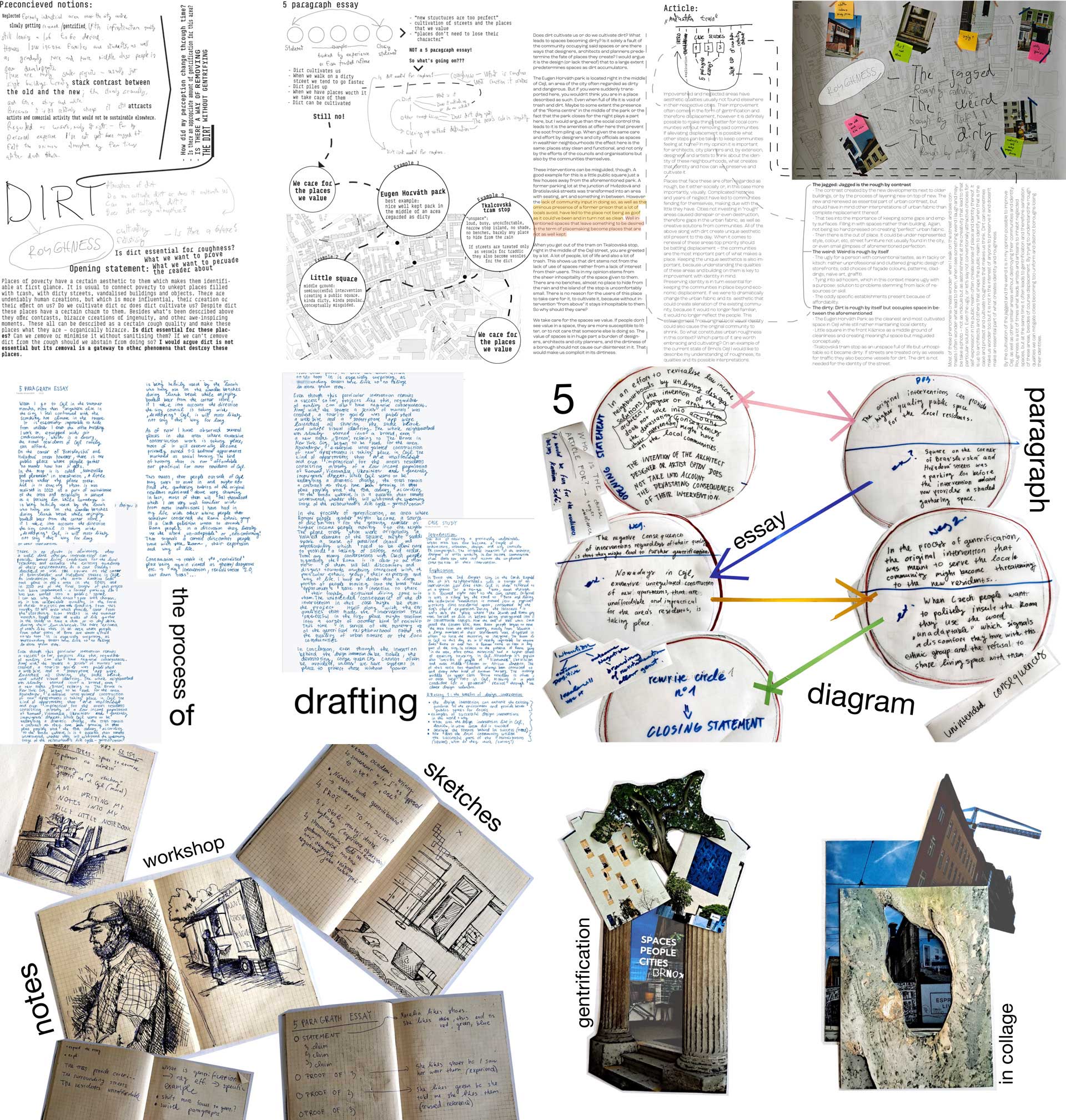

The following days several more visits to Cejl took place, first in the group and then individually. After Ilyin introduced the students to the concept of Peirce’s semiotic triangle, they were supposed to choose something physical on the spot that could represent the idea that their essay would focus on. Ilyin explained the structure and meaning of a 5-paragraph essay as the basis of an argumentative text, as well as how it can be used as a guide for more extensive writing. On the third day, when the students had developed their ideas, Ilyin assigned them to draw a diagram: 5 circles representing the individual paragraphs, containing the essay thesis as well as the arguments. These were drawn on large sheets of paper, and the participants used their own notes and printed photographs and a map of the area—everyone had one at their disposal and could draw on. The remaining days were devoted to the second draft of the essay and the completion of collages representing the thought process. The advantage of a small group was that Ilyin could consult the work on an ongoing basis and the participants could also see how others were progressing in their thinking and writing, which enabled some of the more experienced participants to write not only a short essay within the given limit, but even a more extensive text.

There were several valuable observations made by the participants, as one reacting to the spread of rumours that circulate about Cejl: “In some parts, we don’t know where Cejl begins or ends, so the stories can be questioned: Did they happen in Cejl or just nearby?” Therefore, is this story really about Cejl? Another participant noticed how people judge the area without stepping off the tram, and suggested the importance “to step off the metaphorical ‘tram of expectations,’ putting one’s foot on the ground again and again and have the courage to own experiences in the here and now.” The workshop demonstrated how a method that allowed participants to focus on the process of thinking and writing, thanks to their own experience of a place enabled them not only to identify and articulate an interesting issue, but could transform their initial thoughts about Cejl, some of which were also based on popular rumours. The participants proved their ability to perceive the situation holistically and with respect for the local Romani population whom they saw as actors that should be part of the further development of the place.

Fig. 2: A collage showing the process applied in the workshop, which consisted of mapping, diagramming and several phases of writing. Image: courtesy of the workshop participants Viliam Šebora and Veronika Mikulová.

References

Flodrová, Milena. 2025. Cejl. Encyklopedie dějin Brna, 9 April 2025, https://encyklopedie.brna.cz/home-mmb/?acc=profil-ulice&load=682.

Getzels, Jacob W., Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. 1976. The creative vision: A longitudinal study of problem finding in art. New York: Wiley.

Ilyin, Natalia. 2019. Writing for the Design Mind. London: Bloomsbury.

Karel Kuča. 2000. Brno. Vývoj města, předměstí a připojených vesnic. Brno: Nakladatelství Baset.

Rowe, Peter G. 1991. Design Thinking. Cambridge, Mass. London: The MIT Press.

Šedá, Kateřina, Palán Aleš. 2016. Brnox. Brno: Kateřina Šedá; Tripitaka, z.s.

Sidiropulu Janků, Kateřina. 2013. “Krajina vzpomínek. Kdo kreslí mapu ‘brněnského Bronxu’? / The Memories Landscape: Who Draws the Map of the ‘Brno Bronx’?,” Sociální studia / Social Studies 10, no. 4: 58, https://doi.org/10.5817/SOC2013-4-57.

Double Consciousness Towards a Decolonial Critical Theory, History, and Practice of Landscape Architecture

Burcu Yiğit-Turan

In January 2011, after more than twenty hours of travel from Istanbul—including a three-stop flight, and more than an hour’s drive on the flat, monotonous Indiana interstate highways once built to test General Motors cars—I sit in a university lounge in the Midwest, with the television open, about to start a new academic position. There is a Bloomberg channel commenting the Arab Spring, showing clashes in the dark back streets of Cairo where military forces are suppressing the demonstrators. The words ‘vandalism’ and ‘disorder’ are persistently used. On the screen black boxes off to the side show green and red numbers, indicating the falling and rising values of stocks on the market. There are no statements from the demonstrators. No reflective commentary on their struggles, imaginations for the future, or the current state of everyday life and social and political conditions there, or how these developments will affect the fate of the region. The commentary is focused on how these events will affect the ‘economy’ and ‘gas prices’ in the US. At that moment, sitting in that lobby, a lot of fragmented thoughts flashed through my head, and my heart was wrenched. What is striking is that, fossil fuels have connected these two geographies in a connection of “accumulation by dispossession” (Harvey 2003), having a profound impact on racial, classed, and gendered socio-material realities—oppression in one region is regarded as irrelevant to the other.

This kind of knowing the world resonates with the dominant spatial and environmental histories in planning and design education, redirecting the focus to the ‘frontier’ where subaltern struggles are out of frame, hyper-invisible, irrelevant, and almost non-existent. Ruined worlds are non-performatively and non-relationally imagined in the background as ruined because of their own intrinsic inferiority. The histories are categorized geographically from a Euro-centric perspective as if there is no-connection between them. Theories are universal, and practices are always neutral, or even morally superior. The states of two different geographies, and their societies, are usually conceived as emerging from ‘their own culture and history,’ implicitly entrenching a disconnection, and a hierarchy of inferiority/superiority moralising the ignorance and denial of connection, colonial co-constitution, and accountability. Isn’t it the “colonial” way of knowing the world (Quijano 2007)? Gayatri Spivak defines such an ideology of other worlds (especially of the South) as ‘ontopologocentric,’ which “denies access to the news of subaltern struggles against the financialisation of the globe” (1995:71).

In the context of the climate crises and social upheavals, academics, students, and practitioners in Western contexts related to the production of the built environment seek to understand and address socio-spatial and environmental problems. Our understanding of histories, theories, and practices however, still requires challenging knowledges disconnected from the account of the broader context of the modern/colonial world system, which encompasses the colonial and racial dynamics of capitalist land accumulation, resource appropriation, and labour exploitation at planetary scales (Mignolo 2000). “White spatial imaginaries” (Lipsitz 2007) infuse into our epistemologies as unspoken norms, if they are not countered. In such a context, spatial and environmental knowledges in planning and design are dominated by the White gaze, which prioritises the making of the ‘frontier,’ forgetting that the “magic” of designed landscapes is that they “forever mask…the work that makes it” (Mitchell 2017, 188-192). This illusion helps us forget the landscape’s ‘dark side’—erasure, displacement, dispossession, relations of labour, land, and communities exploited and ruined for its production—that extend beyond the city’s physical boundaries (Dantzler 2024). Enabled through planetary urbanization, landscape “draws us in” with its seductive imaginary, and creates a psychologically distant and safer perspective (WJT Mitchell 2002). Unfortunately, common sense ‘progressive’ aspirations generally fall into re-imposing “White spatial imaginaries,” even onto concepts such as desegregation, social and environmental sustainability, green transformation, urban renewal, safety, or place-making. These are often conceptualized in self-referential vacuums if we do not comprehensively engage with histories, theories, and practices of the built environment within a broader matrix of colonial and racial capitalist accumulation. This is an epistemological injustice, organised non-knowing, reflecting a culture rooted in a “serious split in our consciousness” designed to reproduce the Empire (Said 1994:12). We are left to operate within superficial sustainability frameworks that are oftentimes complicit in perpetuating injustices. Attempts to overarch such a split might disturb the professional and disciplinary myths, easy ‘feel good’ knowledges, and investments in our bubbles, which are protected and carefully managed by a “distribution of the sensible” (Rancière 2004). Many in the field have confronted this epistemic and emotional regime from multiple view-points today.

From the double life every American Negro must live, as a Negro and as an American, as swept on by the current of the nineteenth while yet struggling in the eddies of the fifteenth century, – from this must arise a painful self-consciousness, an almost morbid sense of personality, and a moral hesitancy which is fatal to self-confidence. The worlds within and without the Veil of Color are changing, and changing rapidly, but not at the same rate, not in the same way; and this must produce a peculiar wrenching of the soul, a peculiar sense of doubt and bewilderment. Such a double life, with double thoughts, double duties, and double social classes, must give rise to double words and double ideals, and tempt the mind to pretence or revolt, to hypocrisy or radicalism. (Du Bois (1903(2005), 155–6)

Du Bois posits that Black individuals in late 19th and early 20th century North America experienced a profound double consciousness, stemming from their encounters with racism, differentiation, subjugation, and exploitation. This condition necessitated navigation within a White supremacist society, leading to a constant oscillation between conflicting thoughts, identities, and desires. This double consciousness serves as a fundamental component of racialised modernity, influencing how individuals are positioned on various sides of the ‘colour veil,’ shaping their perceptions and experiences of social realities (Bruce 1992; see also Itzigshon and Brown 2015:235). Du Bois states how African Americans move between these two worlds, the materialistic, capitalist world of White America that dehumanises them while they struggle to survive, and the Black world where they experience the effects of neglect and oppression, as well as Black struggles, agency and urge to revolt and transform. From a Du Boisian perspective, the split consciousness can be interpreted as a system of blindness and self-justification “as a defence of civilisation” (Itzigshon and Brown 2015:244) that enables White society to naturalize the existing racial order even as they strive for justice, centred upon White economic interests, rooted in histories of colonialism and exploitation of racialized people. Racialised subjects, however, can challenge the internalisation of denigration and transform their “double sense into a better and truer self” (Du Bois (1903(2005)).

Du Bois’s theory of double consciousness, which emerged in the context of White supremacy, colonisation, and segregation in the US, could be extended to explore the possibilities of diasporic transnational thinking, with the help of Samir Dayal (1996) and Howard Winant (2009). Samir Dayal (1996) reflects on the phenomenon of diasporic subaltern consciousness to explore the potential of theory to interpret the possibilities of cultivating a transnational consciousness in terms of understanding racisms and creative cultural constructions. A position that challenge those confining diasporic subaltern consciousness to flattening representations that in fact carry knowledge of how global and local inequalities and nationalist ideologies are reproduced. Similarly, Winant (2009) extends this theory by reinterpreting the meanings of double consciousness and ‘the veil’ to capture racial globalisation. In his book ‘The World is a Ghetto,’ he builds upon Wallerstein’s world systems theory to explore the dominant cultural constructs in relation to different geographies and anti-colonial struggles that create ruptures in the processes that construct the modern world system. Dayal argues that “diasporic double consciousness can deflate a Eurocentric manipulation of the machinery of representation, as in neo-colonialist regimes of signification. It can thus enable a deconstruction of the presumption of Euro-American cultural completeness and priority, and it can shatter the illusions of cultural purity,” opening up a politics of representation that recognises that “the representation of the West and the East are not simply two unrelated economies” (1996:54-55). What social justice might mean through negotiation, and hybrid border/borderland experiences in spite of majoritarian discursive practices (ibid.; see also Anzaldúa 1987) offers “possibilities of post-national (transnational) solidarity and belonging” (Dayal 1996:58).

Against this backdrop, various interventions in planning and design scholarship have emerged in parallel during the last decade, providing potentials for developing ‘twoness’ and ‘second sight’ that can counter our disciplinary split consciousness coming to play when we interpret socio-spatial and environmental phenomena. They offer pluriversal, relational, performative, justice-oriented, decolonial critical historical accounts of environments, without flattening them to serve extractive developments. On one hand, they offer epistemologies to comprehend the construction of injustices in urban areas in a Western context; on the other hand, they highlight the injustices occurring elsewhere that facilitate urbanisation in Western cities through labour, material flows, and ruination. They provide inspirations from anti and de-colonial struggles, agencies and imaginaries, whether near or afar. For example, Anna Livia Brand (2018) interprets Du Bois’ theory of Double Consciousness to analyse systemic racism in contemporary urban development in US Cities in order to reveal the persistent practices that undermine Black claims to urban space, history, agency, and vision. Through making residents’ articulation of their experiences—which expose the racial dynamics of urban planning—visible, she portrays the ways in which urban development prioritises capital and White privilege over the expansion of residents’ social and spatial rights. Jane Hutton in her book ‘Reciprocal Landscapes: Stories of Material Movements’ (2020) examines material extraction and labour exploitation, linking renowned public landscapes like Central Park and the Highline to locations in Peru and Brazil. Fabiola López-Durán explores the importation of eugenics and Whiteness from early 20th-century European architecture and planning to modern landscape architecture in Brazil, which contributed to the racialisation of society in her book ‘Eugenics in the Garden: Transatlantic Architecture and the Crafting of Modernity’ (2018).

In light of these considerations, I have revised the course, Landscape Architecture, History, Theory, and Practice at SLU (2025). This course has challenged the split consciousness embracing such rapidly increasing examples in the fields of planning and architecture, theorizing connected invisible spatial and environmental histories, struggles, and activism. Engaging critical theories across various disciplines, such as urban and environmental sociology or urban political ecology, in the teaching of environmental and spatial histories and theories highlights the intellectual gap present in our fields relative to others.

Today it is critical to cultivate consciousness in the fields of planning and architecture by revising histories, theories, and practices to help us build solidarities across various geographies—transnational, national, or local—that can guide us in “imagining and building democratic, just, and non-imperial/colonial societies” (Mignolo 2009, p.2). This is particularly crucial in light of the growing injustices stemming from the ever-evolving dynamics of internal and external imperialism, authoritarianism, privatisation and securitisation, which shape material realities and socio-spatial relationships across various geographic regions. As I curate course material and processes, the actual content emerges differently each year in dialogues about the course material, interactions, events, and co-learning/production in the class. Each student, coming from different backgrounds, takes this journey differently, deconstructs and ascribes different meanings, and formulates different positions in different ways; each year the group dynamics change within the group mosaic as well as the surrounding political and social atmosphere. Despite the odds, and the emotional, pedagogical, and intellectual labour required, the hope remains that such an environmental learning/unlearning approach keeps open the possibility for planetary care and justice.

References

Anzaldúa, G. 1987. Borderlands/ La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Spinsters/Aunt Lute.

Brand, A. L. 2018. “The Duality of Space: The Built World of Du Bois’ Double-Consciousness.” Environment and Planning D 36 (1): 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775817738782.

Bruce, D. D. 1992. “W. E. B. Du Bois and the Idea of Double Consciousness.” American Literature 64 (2): 299–309. https://doi.org/10.2307/2927837.

Dantzler, P. A. 2024. “Racial Capitalism and Anti-Blackness beyond the Urban Core.” Journal of Race, Ethnicity and the City 5 (1): 106–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/26884674.2023.2279432.

Dayal, S. 1996. “Diaspora and Double Consciousness.” The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association 29, no. 1: 46–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/1315257

Du Bois, W.E.B. 1903 [2005] The Souls of Black Folk. New York: Pocket Books.

Harvey, D. 2003. The New Imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hutton, J. 2019. Reciprocal Landscapes: Stories of Material Movements. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315737102.

Itzigsohn, J. and Brown, K. 2015. “Sociology and the Theory of Double Consciousness: W. E. B. Du Bois’s Phenomenology of Racialized Subjectivity.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 12 (2): 231–48. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X15000107.

Lipsitz, G. 2007. “The Racialization of Space and the Spatialization of Race: Theorizing the Hidden Architecture of Landscape.” Articles. Landscape Journal 26 (1): 10–23. https://doi.org/10.3368/lj.26.1.10.

López-Duran, F. 2018. Eugenics in the Garden: Transatlantic Architecture and the Crafting of Modernity. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Mignolo, W. D. 2000. Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.cttq94t0.

Mignolo, W. D. 2009. “Epistemic Disobedience, Independent Thought and Decolonial Freedom.” Theory, Culture & Society 26 (7–8): 159–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276409349275.

Mitchell, D. 2017 “Landscape’s Agency” In Landscape and Agency (edited by Ed Wall and Tim Waterman). Routledge. 188-192.

Mitchell, W.J.T. 2002. Landscape and Power. (Second edition). The University of Chicago Press.

Said, W. E. 1994. Culture and Imperialism. Vintage Books: New York. P.12

Rancière, J. 2004. The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible. The Continuum.

SLU. 2025. https://student.slu.se/en/studies/courses-and-programmes/course-search/course/LK0313/10142.2526

Spivak, G.C. 1995. “Ghostwriting.” Diacritics 25, no. 2: 65–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/465145.

Quijano, A. 2007. “Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality.” Cultural Studies 21 (2–3): 168–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601164353.

Yiğit-Turan, B. 2025. “Is Landscape Colonial?” In Landscape Is…! (Gareth Doherty and Charles Waldheim eds.). Routledge. 42-65.

The Complementarity of Spatial Practices of Decolonising the Mining Landscape

Lis-Mari Gurák Hjortfors and Karin Reisinger

Fig. 1: Workshop contribution by an anonymous participant. Photo: Karin Reisinger, 2024.

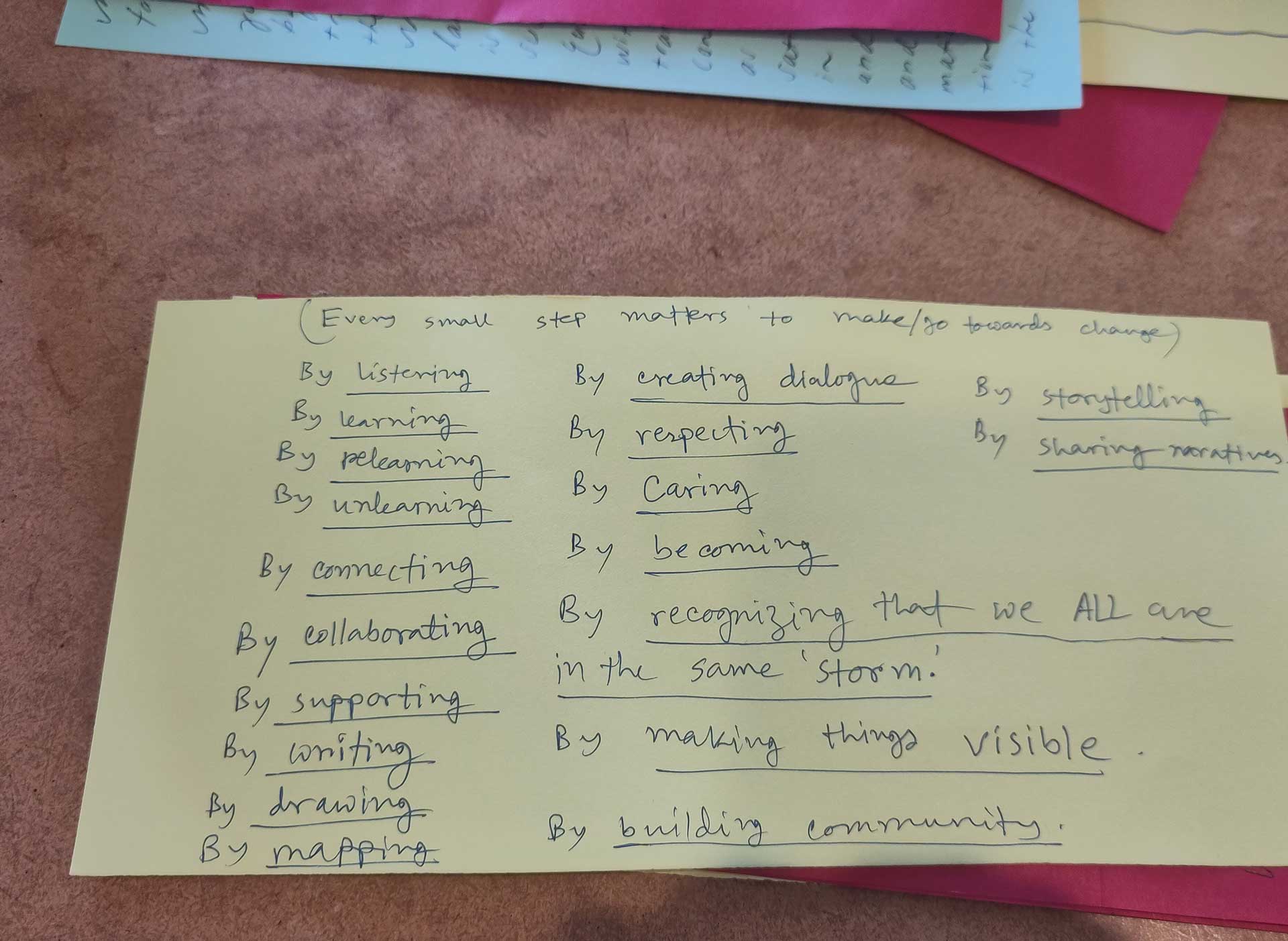

During the Learnings/Unlearnings conference workshop we collected potential spatial practices for the decolonisation of the mining area in Sápmi / Northern Sweden. We asked the question “How can you support the Indigenous decolonial struggle against extractivism with your practice?”

Gällivare is one of the mining towns on the Swedish side of Sápmi—the land of the Indigenous Sámi people—which has been colonized by the Swedish state hand in hand with the extraction of its iron ore resources. You could say that the area where the Sámi live is surrounded by mining activities. Near Gällivare/Malmberget/Koskullskulle we also have the Aitik Boliden copper mine. The mining areas cut off migration routes of reindeer, disrupting the ability of the Sámi from exercising their livelihood.

After meeting for the first time in 2016 in Gällivare to discuss the absence of Sámi narratives in local urgent heritage practices, the conference workshop “Spatial Practices of Decolonising the Mining Landscape” is the first collaboration of the local Sámi ethnologist Lis-Mari Gurák Hjortfors and architect and researcher Karin Reisinger after eight years of continuous exchange. In this short essay we demonstrate how our spatial and pedagogical practices complement each other, and how we invited the conference audience into the process.

Fig. 2: Sámi woman in Malmberget. Private collection Lis-Mari Gurák Hjortfors.

Kicking off the workshop, as a Sámi researcher in ethnology, I discussed the importance of the Sámi taking care of their own cultural heritage, and their rights as Indigenous people. I am a part of an Indigenous people, the Sámi, who have lived in this area long before the place became a mining community (see Fig. 2). Váhtjer/Gällivare municipality—with the three towns of Gällivare, Malmberget, and Koskullskulle—is a mining community with a harsh climate for the Sámi. Today you can barely see Sámi culture and history in the cultural environments. When people talk about Gällivare-Malmberget-Koskullskulle today, they define the communities as mining communities. How do you interpret the past? The Sámi people have lost their cultural heritage. The right to a Sámi cultural heritage is about the right for them to interpret their history. When you travel in the landscape, you can hardly imagine that there are Sámi traces, but if you have the knowledge and look with a “Sámi lens” you will see traces of a cultural heritage—this must be explained to others so that they understand. The Sámi people who have lived in the area for centuries know that the communities are affected by mining activities, and have passed on the knowledge about the migration routes of reindeers, and which areas had good grazing from generation to generation.

The central challenges are how to create equal power relations, diversified cultural knowledge, and research that is broader than the research accepted by majority society, but which may be ineffective for Indigenous people. The first thing a majority society should do to make the Sámi visible and heard is to accept that the Sámi way of life is to live in harmony with nature and animals, which must take place on equal terms with industrialization. The Sámi people want to live in harmony with the surrounding society, but unfortunately the colonization of the Sámi cultural heritage is still ongoing.

Fig. 3: The open pit in Malmberget, Gällivare in the background. The pit is increasing in size due to underground mining. The town of Malmberget will not exist in the future. Photo: Lis-Mari Gurák Hjortfors, 2013.

Fig. 4: Neon signs of former shops in Malmberget. Photo: Lis-Mari Gurák Hjortfors, 2024.

I’ve been fighting against the invisibilization of the Sámi population of a mining town, where the Sámi feel that their culture, history, and rights are not respected in reports, publications, and research made by non-Indigenous people. You can read articles and publications where they “have forgotten” the Sámi people, and it is common knowledge that colonization just continues. I have discussed this with Lulesámi people whom I have interviewed for my doctoral research (Gurák Hjortfors, 2023). To avoid making the Sámi invisible due to industrialization and colonization, places and identities must be discussed. A society is built upon different historical layers, and a cultural environment can be seen in different ways, depending on who you are and what perspective you have. I have worked extensively on what identity and faith is for the Sámi people, and I have a strong interest in what a cultural environment means, and what happens to people when they lose their cultural heritage. What does colonization do to a people and how can they reclaim their culture and history? I have wondered whether there are places or environments where the Sámi could find a free zone for their culture?

A return to Indigenous cultural heritage provides a means of escaping colonization for the Sámi identity, reclaiming a cultural heritage as part of the work of reconciliation, and strengthening a feeling of belonging (Hjortfors 2021). I bring the place to life, reconnecting it to the cultural and natural environment by conveying knowledge and providing counter-images through soft-activism and poetry—fighting the threats which make Sámi culture invisible. I want to change people’s minds and educate the public about Sámi culture in Gällivare-Malmberget-Koskullskulle through texts, photos, poetry on-stage performance, exhibitions, and other pedagogical methods (Hjortfors 2022).

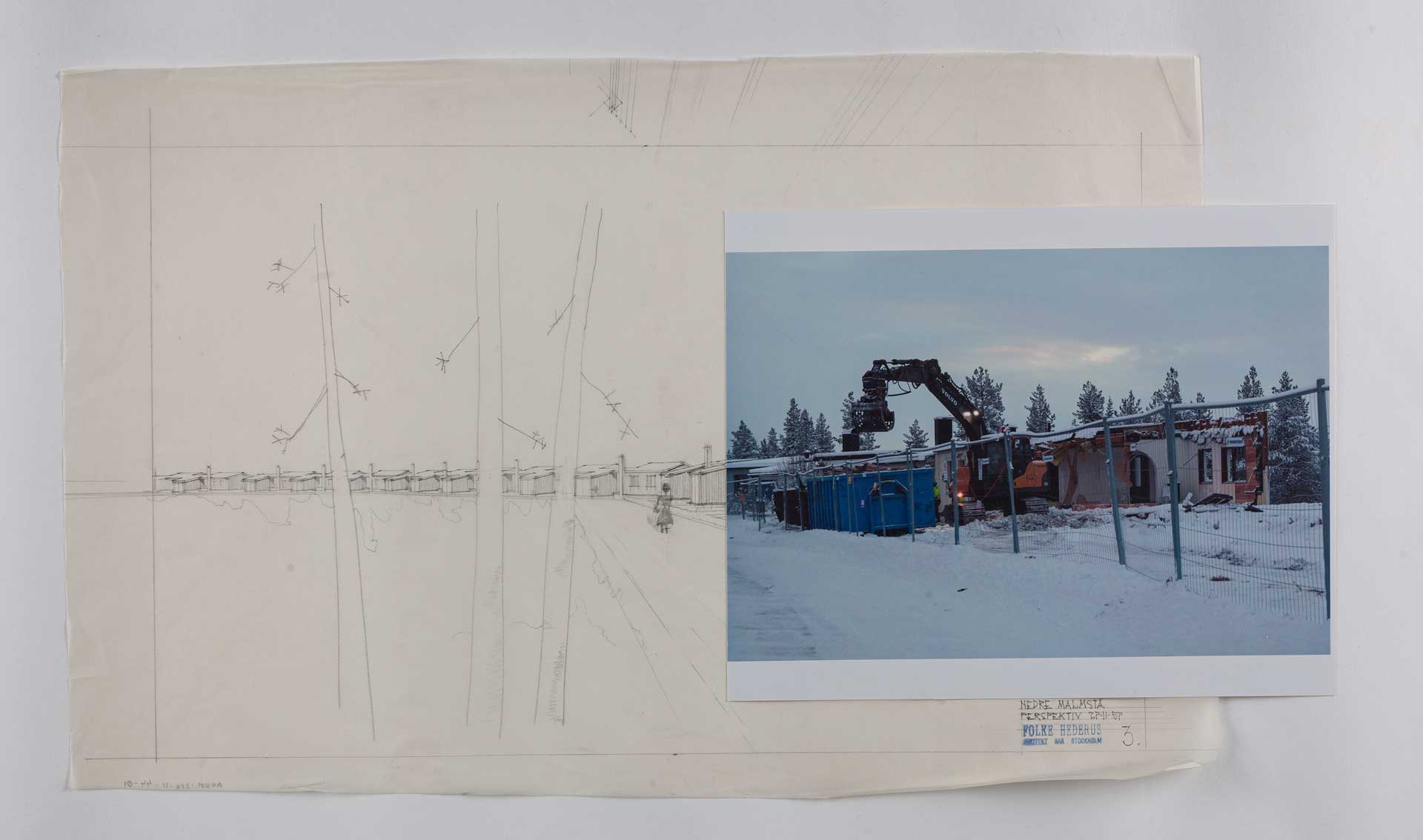

In response to Lis-Mari Gurák Hjortfors’ claims and due to my education in architecture and my socialisation in Central Europe, I am interested in Architecture’s role in extractivism. Since 2016 I have been visiting the mining community of Malmberget-Gällivare regularly. Malmberget is a disappearing mining town, whose population has shrunk from over 10,000 in the 1960s to much less than 1,000 today, with only a couple of building blocks and houses remaining. Areas such as Gällivare provide building material for the whole of Europe—through the extraction of iron ore—and a large part of this material goes into the building industry all over the world. There is (at least) a twofold role of architecture in this extractivism, which is closely tied to colonialism. Firstly, materials have to be mined, which causes local extractive violence (Sehlin Macneil, 2017). The state-owned mining company LKAB mines 80% of Europe’s iron ore (lkab.com), and not far from Gällivare lies the privately-owned Boliden Aitik mine, which primarily mines copper. Secondly, Architecture provides the infrastructure needed to enable mining, such as housing for workers. LKAB commissioned Sweden’s most influential architects to ensure high quality living standards above the polar circle (Reisinger 2024A). The relationship between architectural infrastructures and extractive destruction is complex, and I have tried to open up discussions by visualising this complex relationship.

Fig. 5: Lifelike Appendix to the Archive No. 1 (2018), collage by Karin Reisinger, based on a drawing by Folke Hederus (1957) and her own photography. ArkDes Collections, photographed by Björn Strömfeldt, 2021–2022.

Based on material relationships, my own involvement in the architectural profession and education, and not least on multiple conversations with Lis-Mari Gurák Hjortfors over the years, I have been following the Sámi (and) feminist practitioners of the area and exploring the spatial practices they apply to deal with the loss of their homes (Reisinger 2024A, 2024B). Pernilla Fagerlönn, for example, organised and curated an exhibition for the last remaining high-rise building in 2019, which I had the honour to contribute to. After a long involvement in the community, I had to ask, how can the local violences from mining—and above all the local literacies of dealing with loss and extractivism—be mirrored back into the community of architects to discuss the material responsibility of building?

My engagements are based on an anti-colonial perspective, transformed into pedagogical formats of presentations, talks, writings, collages, and exhibitions, emerging together with situated local spatial practitioners in mining areas. A special collaboration in 2024 was exhibited at Rotterdam’s International Architecture Biennale (IABR), with the topic “Nature of Hope.” It allowed us to produce further videos with the local practitioners. Together, Lis-Mari Gurák Hjortfors, Pernilla Fagerlönn, who wrote a musical about the disappearing mining town Malmberget, Karina Jarrett, who founded the local embroidery cafe, and Miriam Vikman, who walks a traditional path in the woods to save the ecosystem from clearcutting, we contributed narrations of local practices in video formats. The installation was supported by Lena Sjötoft, who contributed her political knowledge on the impact of mining on the four different Sámi communities whose territories coalesce in Gällivare, and further by embroideries by Karina Jarrett and Eeva Linder. The installation was a way for me to continue learning from the local knowledges of the mentioned practitioners, and to share this knowledge in pedagogical format with visitors to the biennale.

Fig. 6: Listening Station on Practices of Hope amidst Extractive Violence at IABR 2024. Karin Reisinger, Pernilla Fagerlönn, Lis-Mari Gurák Hjortfors, Karina Jarrett. Photo: Jacqueline Fuijkschot.

With these examples we hoped to further inspire architectural practitioners to think about how they can contribute to the shared task of decolonising mining areas—for example being aware of building with materials extracted from Indigenous lands, or planning with respect for or with Sámi communities, which eventually leads to more Sámi voices in architectural education and practice, enabling self-determination (see the pyramid of the way to Sámi self-determination by Hirvonen and Balto 2008; Balto and Kuhmunen 2014, 39; Keskitalo and Olsen 2024, 39-40). A persistence in looking for ways of responding to the Northern extractivism from within the conflicted discipline of architecture is the basis of our joint workshop at the conference, where many creative practitioners were present.

In the workshop, we (Lis-Mari Gurák Hjortfors and Karin Reisinger) discussed with the participants of the conference “Learnings/Unlearnings” how each of us can contribute to the Indigenous struggle with our spatial and cultural practices of producing and sharing. After an intense discussion of the situation in Gällivare from a Sámi perspective, and examples of collaborations and responses, we asked the workshop participants: “How can you support the decolonial struggle through your practice?” For some this was difficult, for others not at all, depending on their varying experiences of extractivism and colonialism. Most of the international participants were new to the situation of extractivism in Sápmi and had many questions about the effects and unexpected details of extractivism, which Lis-Mari generously and patiently answered. The participants of the workshop collected ideas about supporting the decolonial struggle, of which Gällivare is an example (see also the collection of activating verbs at the beginning of this text), noting their ideas and sharing them. Among the following, the participants aimed for:

“bringing these questions into the classroom”

“supporting with research/teaching/practice collaborations”

“connecting with other researchers working with indigenous people”

“researching and visualizing recolonised / (neo-colonial) occupation”

“revealing the hypocrisy of the government through waiting, participating in activism, following the sámi media, and helping to bringing the voice of the struggle to public forms”

“spread awareness and everyday choice of what to consume, or better, to reduce consumption”

– workshop participants

The main aim of the workshop was to learn from each other, and show that the applied pedagogical methodologies and formats complement each other in our shared aim of restoring healthy relationships to places and environments beyond extractivism and colonialism. Across countries, contexts, languages, and formats, and between research and cultural production, the hard task of decolonisation needs multiple voices and approaches. It requires not only multiple formats, but must also transgress the multi-layered compartmentation of cultural production and knowledge dissemination with these formats to come together in the shared aim of decolonisation—of Malmberget-Gällivare, but also of our disciplines and our practices.

We understand ourselves as researchers, and through our roles with different positionalities we complement each other through our perspectives on the researched areas. We apply different practices which come from different learnings and experiences. But that does not keep us from collaborating from time to time and coming together in the intersections of our practices and struggles in which we both learn from each other. The decolonial and anti-colonial strategies of a variety of pedagogical formats allowed for dialogue, and led to further communications and collaborations, which are still ongoing. We are thankful for the generous contributions of the workshop participants and their support in a long-lasting struggle.

See the conversational videos here:

“Lis-Mari Gurák Hjortfors on her work with Sami heritage”

“Pernilla Fagerlönn on the Farväl Focus festival”