Learnings/Unlearnings: Transgressing, Conversing, Performing

MYCKET (Mariana Alves Silva, Katarina Bonnevier, Thérèse Kristiansson), Nadia Bertolino, Janna Lichter, Mudita Pasari and prachi, The Gröndal Bureau of Investigation (John Maclean), Johanna Gullberg, Sylwia Janka Poltorak, Architectural Thinking School (Elena Karpilova and Alexander Novikov), Zest (Lu Herbst, Lucie Jo Knilli, Charlotte Perka and Lioba Wachtel)

CATEGORY

Welcome to Learnings/Unlearnings Reader #5: Transgressing, Conversing, Performing, guest edited by Emilio Brandao, Anette Göthlund, and Meike Schalk. The Reader includes contributions from the section, “Building and Playing: Processes, Props, Materials, Media, Techniques,” from the conference Learnings/Unlearnings: Environmental Pedagogies, Play, Policies, and Spatial Design, which took place in Stockholm in September 2024.

The Reader #5 gathers contributions that explore “performance” as a pedagogical mode of transgression, conversation, transformation, and intervention. Performance here goes beyond staged action, becoming a method of learning that unfolds in embodied encounters, collective practices, and material improvisations. To perform pedagogy is to risk uncertainty, to enter a dialogue with others—human and more-than-human—and to disrupt the boundaries of disciplines, institutions, and everyone’s roles. The papers in this collection move between theatre plays, nomadic workshops, feminist media practices, absurd architectures, children’s games, and institutional fictions. They demonstrate how performance generates forms of knowledge that are situated, relational, and actively resistant to capture by conventional academic frameworks. Whether through play, storytelling, dialogue, or spatial experimentation, these contributions highlight how performing pedagogy can create cracks in normative structures, making space for care, solidarity, sharing, and imagination. Together, they propose performance not as representation, but as a lived practice of unlearning and reworlding.

In the first paper “Troll Visions,” the collective MYCKET explores “troll perception” as a practice of unlearning extractivist and capitalist logics while cultivating alternative modes of seeing, hearing, making, and dwelling, with the Earth. Emerging from their artistic research project Troll Perception in the Heartlands, the paper recounts site-specific experiments in storytelling, craft, and collective making with children, communities, and local matter, at Utsikten—a pedagogical garden outside ArkDes in Stockholm. Drawing on folktales, queer and Indigenous methods, and ecological temporality, MYCKET proposes a shift from “designers” to “shapeshifters”—practitioners who tend, rather than produce, and who enter reciprocal relations with materials and myth. Through playful gestures, from slicing apples (part of their presentation at the conference), to awakening trolls beneath bedrock, the work enacts performance as pedagogy—a way of opening imagination, disrupting normative narratives, and reorienting design toward care and kinship with the more-than-human worlds.

In the paper “Transgressing Boundaries: Reimagining Civic Institutions through Nomadic Architectural Pedagogy,” Nadia Bertolino examines how nomadic architectural pedagogy can unsettle entrenched hierarchies and reimagine civic institutions through practices of collective care and feminist spatial engagement. Drawing on the Micro Civic Institutions of Care workshop held in Glasgow with architecture students and local residents, the paper describes a methodology where learning takes place in the streets and everyday spaces of the city, rather than in the studio. Through ephemeral interventions, collaborative collages, and site-responsive encounters, participants tested how architecture might shift from permanence and spectacle toward inclusivity and solidarity. Inspired by critical and feminist pedagogies, the paper foregrounds embodied, situated learning that collapses boundaries between designers and communities. Here, performance operates as transgression, making visible neglected forms of care and animating speculative civic imaginaries for more just and compassionate urban futures.

The paper “Practices of Un-Learnings through Feminist Spatial Conversations and Media Materials,” by Janna Lichter, explores how feminist spatial conversations and media practices can open spaces of “un-learnings,” disrupting dominant pedagogical frameworks and visual narratives. Moving between teaching, research, and artistic practice, the author develops video-based dialogues that foreground lived experience and collective sense-making. Rooted in intersectional feminist pedagogy, these conversational practices resist hierarchies of knowledge, instead cultivating relational ways of seeing and knowing. Drawing on the author’s seminar at the University of Applied Sciences Düsseldorf and the ongoing Queer-Feminist Spatial Conversations series, Lichter shows how experimental audiovisual work can challenge systemic inequalities and hegemonic media representations. By centring care and desire as collective practices, the paper imagines feminist educational spaces as performative acts—dynamic encounters where conversation, media, and pedagogy converge, to nurture solidarity and creativity towards transformative futures.

In “from unstructured dialogues,” Mudita Pasari and prachi reflect on their experimental project power OF space (pOs)—a series of unstructured dialogues exploring how learning might unfold beyond academic boundaries. Conceived as a social experiment with a small cohort of collaborators, pOs foregrounded space, not as property or asset, but as a dynamic process of negotiation and collective becoming. Season 1 unfolded in physical sites across India, where playful encounters and vulnerability became catalysts for equity and shared knowledge. Season 2 moved online, opening new possibilities for archiving, layering, and visualizing conversations across geographies and identities. Through play, placemaking, and collective subversion, pOs generated an evolving commons of learning, challenging institutional authority while nurturing courage and co-ownership within alternative pedagogical futures.

John Maclean presents the project Gröndal Bureau of Investigation (GBI), a semi-fictional, self-instituted public institution that playfully reimagines attention as a civic practice. Emerging from artistic research in Stockholm’s Gröndal district, GBI investigates everyday relations between humans, buildings, technology, and the more-than-human world. Through “fictioning” and autofictional strategies, it stages investigations that use sensory evidence, public boxes, and online/offline platforms to recalibrate how ecological consciousness might emerge within the attention economy. Blurring fact and fiction, Maclean introduces GBI as an institutional voice, yet through the persona of “The Wretched Painter,” also highlights performance as a method of institutional critique and world-making. The project proposes alternative imaginaries of public space, care, and degrowth, inviting participants to unlearn distraction and reorient attention toward multispecies entanglements and ecological futures.

In “An Architectural Play for Learners,” Johanna Gullberg transforms a doctoral research project into a theatre play that reimagines architectural education through performative dialogue, and spatial storytelling. Drawing on the author’s thesis, “Cogenerating Spaces of Learning,” the work stages fictive characters, shifting environments, and architectural drawings as provocations for learners to step outside conventional studio practice. Inspired by collaborations with theatre artists, the play highlights the transformative potential of materiality, corporeality, and risk-taking in design education. Characters like students Cyndyn and Alice, a disillusioned professor, and a whimsical performance artist navigate evolving learning spaces where nonhuman actors also come alive. By combining script, stage directions, and architectural diagrams, Gullberg’s play becomes both research dissemination and pedagogical tool. It becomes an accessible, performative experiment inviting learners and educators to critically reimagine habits, embrace uncertainty, and rediscover architecture’s socio-ethical and imaginative dimensions.

In the paper “Up Side Down Inside Out Educational Surrounds,” Sylwia Janka Półtorak investigates how absurdity and playfulness can serve as critical tools in rethinking architectural and educational environments. Drawing inspiration from Shusaku Arakawa and Madeline Gins’ Reversible Destiny projects, the paper explores how disorienting, unconventional spaces provoke embodied learning and heightened sensory awareness. In contrast to screen-based, sedentary modes of education, such “procedural architectures” invite learners to move, balance, and engage with their environments in unexpected ways, fostering well-being alongside intellectual growth. Through references to pataphysics and speculative design, Półtorak situates absurdity not as novelty, but as a method of transgression, challenging architectural norms, unsettling comfort, and cultivating curiosity. In doing so, the author positions absurd, playful spatial practices as powerful pedagogical strategies for nurturing resilience and critical reflection in times of ecological and social uncertainty.

In the paper “Children Anywhere?” Elena Karpilova and Alexander Novikov question how children’s voices, rights, and presence are represented—or mostly excluded—in contemporary urban and cultural spaces. Tracing philosophical and historical understandings of childhood, they critique playgrounds as restrictive “ghettos” that isolate children from civic life, and they highlight art and architecture projects—from Francis Alÿs, to Lithuania’s Children’s Forest Pavilion—that challenge this marginalisation. At the Venice Biennale, their project Bambini Ovunque (Children Everywhere) positioned immigrant children as active urban agents, reclaiming streets through invented games and performances that addressed migration, displacement, and belonging. Now evolving into the IntelliGENS Play Lab for the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025, their initiative frames play as both research and public pedagogy—an embodied, performative practice that redefines childhood as civic participation, and reimagines the city as a playground for collective futures.

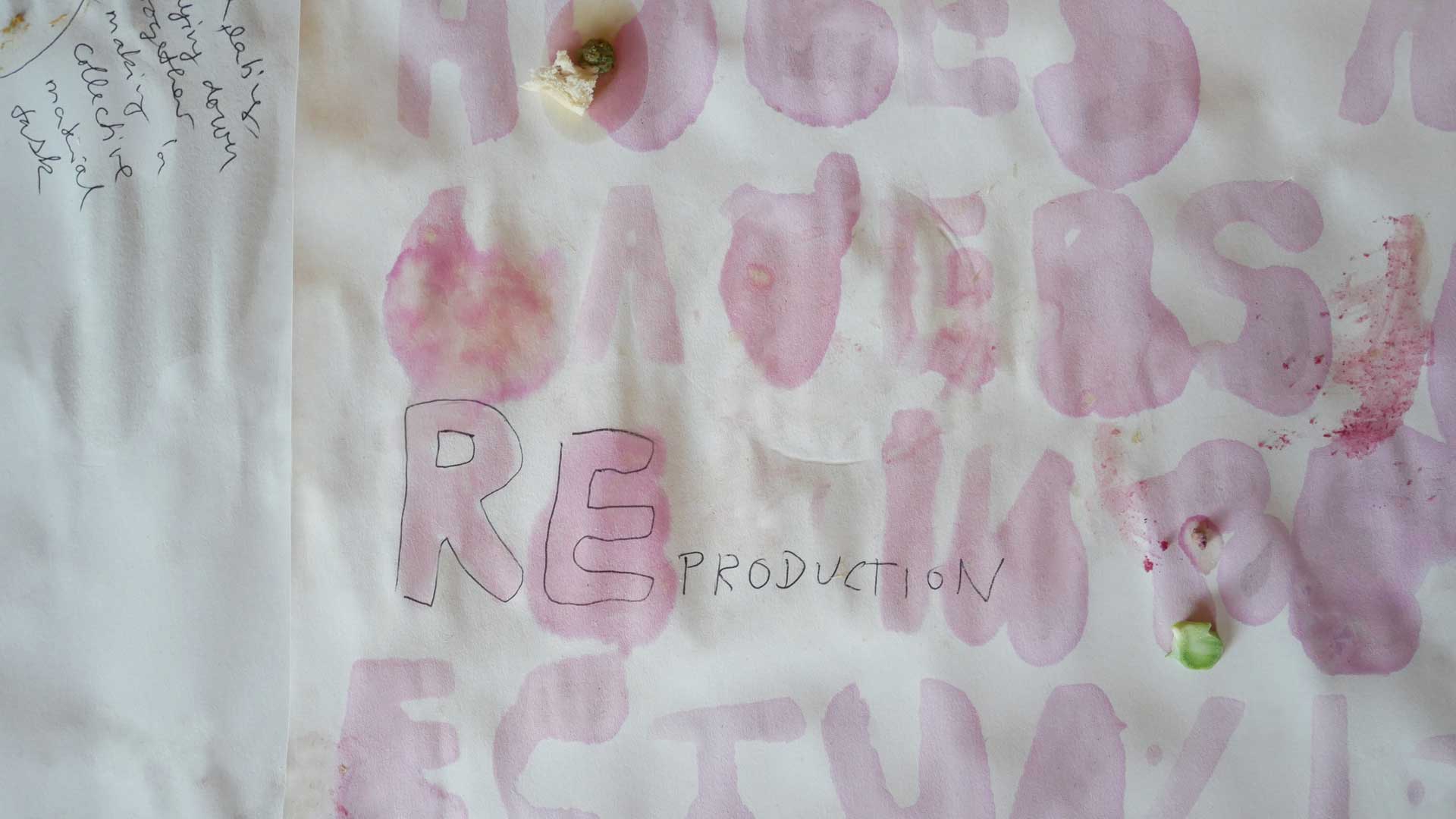

Finally, Zest Kollektiv’s (Lu Herbst, Lucie Jo Knilli, Charlotte Perka and Lioba Wachtel) workshop “Gathering Knowledge in the Gaps Between our Teeth,” stages a multisensory “relational table” to rethink learning through taste, touch, and conversation. By inviting participants to pierce, crush, and chew fruits and vegetables with unusual tools, the collective foregrounds gaps, cracks, and frictions as sites of knowledge-making. Their method resists capitalist and ableist ideals of productivity in education, instead emphasizing unstructured, collective, and somatic experiences, rooted in their broader practice of creating “schools of the not-yet,” the workshop uses food and shared meals as metaphors for digesting institutional barriers and reimagining communal spaces. Through playful acts of serious experimentation, participants explored what it means to unlearn entrenched habits and build solidarities. Here, performance and pedagogy merge as a practice of sensing and slowing down, cultivating alternative ways of being and learning together.

Contents

Form Follows Trolls

MYCKET (Mariana Alves Silva, Katarina Bonnevier, Thérèse Kristiansson)

“Troll perception in the Heartlands – artistic research to widen our imagination capacity,” by MYCKET, Design+Change Department, Linnaeus University, financed by the Swedish Research Council, 2021-24.

This essay explores findings from the practice-based artistic research project Troll Perception in the Heartlands— Artistic Research to Widen Our Imagination Capacity, investigating how design can support a reimagining of our relationship to Earth and the more-than-human. Through site-specific making, storytelling, and material exploration, the project develops “troll perception” as a mode of attention that resists extractivist and technocratic capitalist paradigms. The essay traces work done at Utsikten, a pedagogical and participatory intervention outside ArkDes in Stockholm, where collaborators—including children, artists, and local materials—collectively explored alternative modes of building, learning, and being. Drawing inspiration from folktales, Indigenous and queer methods, and ecological temporality, the project proposes a shift from designers to shapeshifters: practitioners who tend, rather than produce, and who enter into ongoing relations with materials, time, and myth. In this way, the project asks how we might unlearn dominant design ideologies and listen more carefully to the land beneath our feet.

This paper was presented at the Learnings/Unlearnings Conference, held in the embrace of an old pigment and colour manufacturing plant, nestled within one of the few remaining post-industrial fringes of Stockholm. Surrounded by the thousands of bricks that constitute this architectural body, we were reminded of the clay from which each brick is made. Not long ago, clay brick manufacturers could be found all across Stockholm—a testament to the rich clay beds lying beneath our feet, remnants from the melting of ancient glaciers in this part of the world some 10,000 years ago.

The project constitutes a form of artistic research grounded in contemporary practice, aiming to explore how a shared future might be imagined and enabled through cultivating a renewed dialogue with the Earth and our more-than-human companions. The kinds of decisions and behavioural shifts required for deep societal transformation must be accompanied by new conceptual models and patterns of thought. The prevailing narrative still asserts that technological advancement will save us, primarily in the service of maintaining continued economic growth. This dominant, extractivist worldview—what Donna Haraway names the Capitalocene—must be critically interrogated: a capitalist, patriarchal, and colonial logic of domination over the Earth, which consumes and annihilates (Haraway 2016). Our inquiry moves through the landscapes of southern Sweden—terrains shaped by insatiable human desire and marked by production forests, monoculture fields, and expanding urban infrastructures, but also by lush nature reserves, vibrant lakes and streams, disused mines, overgrown landfills, and former industrial sites.

Troll Perception in the Heartlands is a transdisciplinary design research project that expands the formal field of sustainable design by engaging in site-specific acts of crafting, performing, and animating—practices informed by mythology and folktales. The aim is to co-create and share viable ways of designing and living, while re-establishing a dialogue with the Earth and our fellow beings. We engage in participatory learning processes with local communities to remind ourselves of the transformative potential of art and advocacy. We spend time with various materials—blue clay, plastic packaging, cattails—grateful to be hosted by a multitude of sites, as we excavate traditional craft and building techniques that may still have something to teach us about how to dwell with the Earth, rather than live at the expense of it.

We now invite you to enter gently into this unhuman realm. We use the term unhuman to describe trolls—not to suggest they are like us, but to recognise that, despite their difference, they share something with us. Our turn toward folktales and legends is an attempt to reconnect with a time when people in our region saw themselves as subject to nature. We draw inspiration from Indigenous, queer, and trans activist methods from across the world, yet we begin by digging here, where we stand.

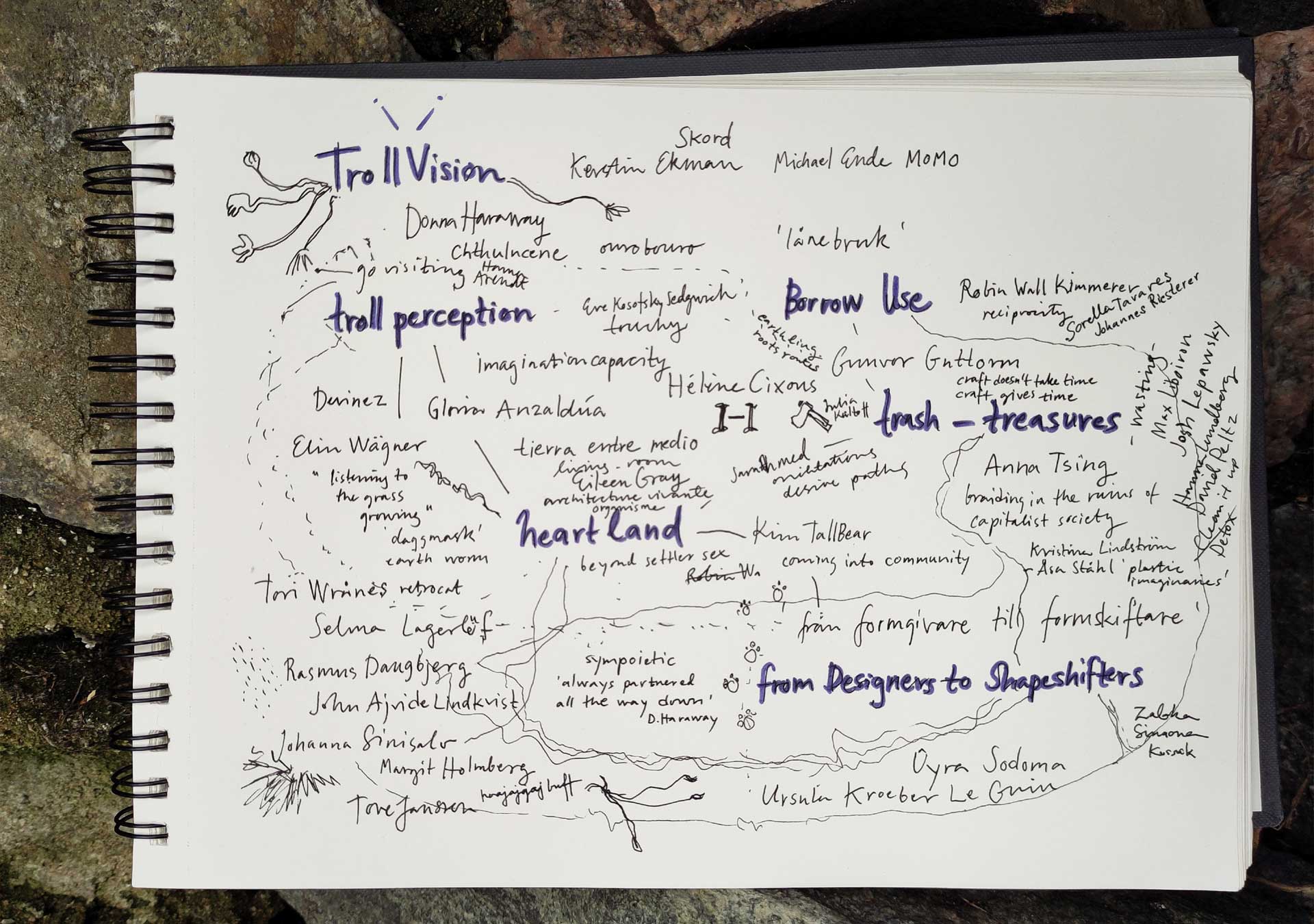

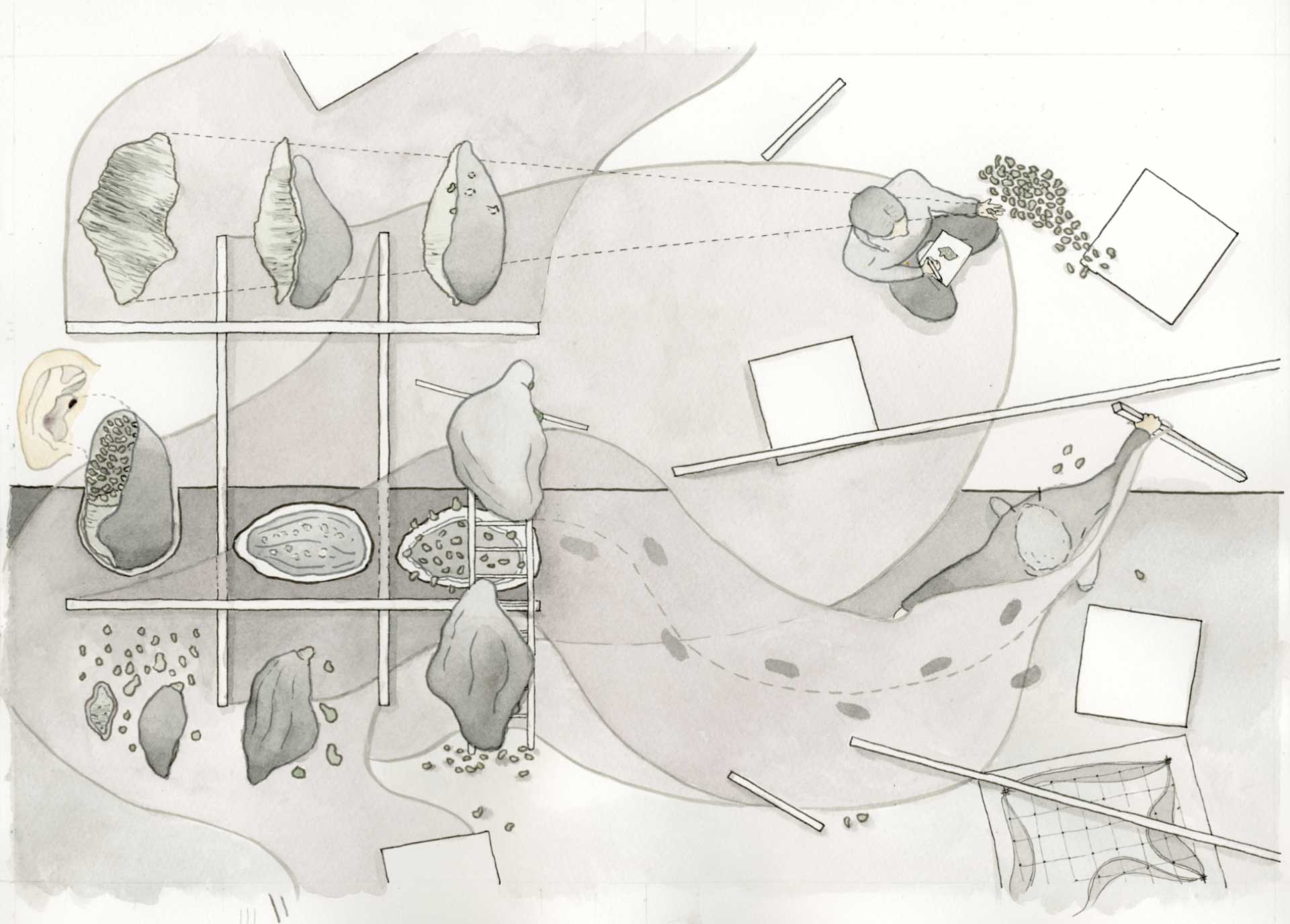

Map of TrollVision, MYCKET, 2024.

A fundamental point of departure in our work is the very concept of troll perception. Rather than defining it in abstract terms, let us illustrate what it does through a simple gesture drawn from our everyday practice.

Take, for instance, the act of slicing an apple for breakfast porridge (at the conference, we cut apples from our gardens and handed them out to the audience). Instead of habitually cutting the apple into wedges—from stem to blossom—we slice it crosswise, along the transversal axis. In this cross-section through the ‘core,’ a star is revealed—most often five-pointed—a delicate, naturally occurring geometry. This tiny, enchanting architecture, which houses the apple’s seeds, becomes what we call a “star house.” With this subtle shift in gesture —a queer orientation, in the spirit of Sara Ahmed (2006)— paired with a playful turn of phrase, the cosmos is suddenly made present—unfolding stories that reach from the celestial heavens to the intimate, earthly constellations of kinship. The star house may also be read as the home of a star family (stjärnfamilj in Swedish)—a term used to describe chosen or non-normative family structures beyond the heterosexual matrix.

In this act of transformation—of form and language—a multitude of stories emerge (there are always more). On the Sámi night sky, the central pole of the lávvu (tent) holds up the celestial dome through what in Swedish is known as Polstjärnan—the North Star. In several Latin American traditions, what in Sweden is referred to as Orion’s Belt is instead known as Las Tres Marías—the Three Marys. These are not merely different names, but different ways of seeing, interpreting, and relating to the world.

Such ways of making meaning—through performative acts of defamiliarization, enchantment, and rupture—form the conceptual and methodological foundation of this project.

In the remainder of this essay, we will focus on the theme of materiality in relation to learnings and unlearnings, as explored through the example of Utsikten: a (proto)institutional space for co-creation, experimentation, and becoming—an evolving work-in-progress located just outside ArkDes, the Swedish Centre for Architecture and Design, on Skeppsholmen in Stockholm.

At ArkDes, we were invited to create a kind of pedagogical garden. Through our cultivated troll perception, our first gesture was to come into contact with the site—not as neutral ground, but as heartland.

For us, a heartland is a site that casts a certain spell—one that speaks to us, touches something within, and activates the imagination. It is a place where we are local, not necessarily by geography, but by presence—where we are able to act with our bodies and affect the space through our gestures. A heartland may be fleeting or provisional—might not be the place we would choose if the entire world lay at our feet—but it draws us in nonetheless. It defies conservative definitions or neat cartographic categories.

The notion of heartlands resonates with Gloria Anzaldúa’s borderlands. Anzaldúa frames the border between Mexico and the United States as a metaphor for all kinds of crossings—geopolitical boundaries, sexual transgressions, social dislocations, and the lived multiplicity of linguistic and cultural identities. Both the borderlands and the heartlands are spaces where the boundaries between the staged and the real are blurred—where it is unwise to separate folktales, myths, and expectations from what we call reality. As Anzaldúa writes: “Nothing happens in the ‘real’ world unless it first happens in the images in our heads.” (Anzaldúa 1987).

Heartlands are thus contaminated, transitional zones—spaces of entanglement between the human, the unhuman, and the more-than-human. When we began to engage with our heartland, we discovered in geological maps that the site rests on the primeval bedrock that lies beneath Stockholm—rock that has been sleeping there for approximately 1.8 billion years. (Imagine: your own lifetime is barely a breath in relation.)

Heartland, The Secret Garden ”Utsikten” at ArkDes, Skeppsholmen, Stockholm, MYCKET, 2024.

And as we looked closer—both with our eyes and with our imagination—we saw a pack of wolf-like trolls lying dormant in the rock, precisely beneath the site now known as Utsikten. A sense of urgency arose: they must be awakened—they are needed to help us avert extinction. Yet such awakening must be done with care.

We decided to materialize an ear from this imagined troll pack—emerging subtly from the ground. Attached to it, an earring in the shape of the Ouroboros, an ancient figure of life’s continuity that dates back to at least 1600 BCE in Egyptian culture, and even earlier in Sumerian mythology (circa 3500 BCE). The ear listens. The circle turns. The troll may begin to stir.

Together with twenty children from the Philosophical Elementary School in Skarpnäck, staff from ArkDes, members of our queer community, representatives from neighbouring institutions on the island, and other living beings dwelling on the island of Skeppsholmen—we began to form a troll pack. This was our way of approaching the dormant trolls, not directly, but collectively, cautiously, through play, presence, and attunement.

Over time, thousands of children, pollinators, tourists, and passers-by also joined in—adding their gestures, movements, and imaginations to the growing field of Utsikten. Through their presence and participation, the site gradually transformed into what it would become: a living, breathing space shaped by many hands, paws, wings, and thoughts.

So how do we build? Through troll perception, we understand that we are, in fact, already living atop a dump—we must create with it, not add to it. Waste is no longer something to discard, but something to be reimagined. We cannot afford to create new waste (as we were once trained to do).

Throughout the research process, we have engaged with and revived building techniques that have long been neglected or nearly forgotten: clay construction methods such as clay plastering and mortar (guided by clay builder and master of masonry Johannes Riesterer); weaving structural forms from twigs and rush; and developing architectures shaped by hand, time, and terrain. These are practices that resist industrial/capitalist efficiency, logic and consumption. As Gunvor Guttorm reminds us: “Hantverk tar inte tid, det ger tid”—craft does not take time, it gives time.

We collaborated with the firm responsible for maintaining Skeppsholmen and Stockholm’s public parks, receiving masses of stems, twigs and branches. At ArkDes, we scavenged disused materials from former exhibitions: aluminium bars coated with glue, torn LED strips, MDF fragments.

Lånebruk, MYCKET, The Secret Garden, Utsikten, ArkDes, Skeppsholmen, Stockholm, 2024. Photos: Sima Korenivski except for image in the bottom middle by MYCKET.

To ensure structural stability without resorting to concrete foundations, we turned to troll competence—particularly the expertise of gardener and artist Simon Häggblom, who showed us that anchoring need not mean excavation. Riesterer supported the clay rendering of sections of the structure. We even received fragments of primeval bedrock unearthed during the construction of the new subway line running directly beneath Skeppsholmen.

This way of working posed a challenge for ArkDes. Although they initially welcomed the idea of an open-ended, participatory process, the realities of bureaucratic procedure intervened: final drawings had to be submitted to the National Property Board in order to obtain a building permit. In the end, hand-drawn sketches—rather than precise technical blueprints—were accepted.

Our ambition for this project was to invite everyone involved—ourselves included—to become shapeshifters: to be affected and transformed by the materials and relations we worked with; to shift others and our own form through encounters.

One such transformation began through our work with the calabash—the oldest known cultivated crop to have crossed oceans unaided. Originating in West Africa, the calabash drifted across the Atlantic to the Americas, where it has served, for millennia, as food, vessel, musical instrument, symbol, and companion. We have begun to grow calabashes ourselves, entering into a relationship of care and reciprocity with this ancient life form—tending to it in different ways, allowing it to shape us as much as we shape it.

From Designers to Shapeshifters, MYCKET, The Secret Garden, Utsikten, ArkDes, Skeppsholmen, Stockholm, 2024.

The calabash also appears in Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, where she proposes an alternative narrative structure—one that centres relationship, cooperation, and care. In her essay, Le Guin challenges the conventional arc of the heroic tale: what if the story of the world were not told through the weapon, the conqueror, or the lone explorer, but through the container, the vessel, the gathering gesture?

Such a shift invites us to rethink both form and creation—not as linear progress driven by individual genius, but as a practice rooted in interdependence between materials, technologies, ecosystems, and people. The calabash carries a different kind of origin story—one that holds the potential to unsettle dominant narratives and open pathways toward other ways of understanding the world.

Whether we succeeded in turning ArkDes into shapeshifters remains uncertain—perhaps a few were transformed. But institutions can be thick-skinned (children less so— troll perception is seldom strange to them). The prevailing idea that design is something to create—rather than something to tend—still dominates. We know this, because we were trained within that very paradigm: one based on consumption, production, and waste. On asserting a singular, human-centred perspective.

This logic trickles down into the expectation that children, when attending a workshop at a design museum, must make something—build an object they can carry home, or witness the immediate result of their labour. But what if we instead taught them that design is an act of care? Of tending to something whose result may not be visible within their lifetime? Of watering, maintaining, mending?

This is the essence of the now: understanding that time—not material—is our most precious resource. Time is all we have, it’s the resources that are finite.

The subject of our presentation emerges from our artistic research project, Troll Perception in the Heartlands: Artistic Research to Widen Our Imagination Capacity, funded by the Swedish Research Council and based at the Department of Design + Change at Linnaeus University (2021-2024).

References

Ahmed, Sara, 2006. Queer Phenomenology: Orientation, Objects, Others. Durham: Duke University Press.

Anzaldúa, Gloria, 1987. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Guttorm, Gunvor, 2022. The AIDA project as starting point for duddjoma development work, keynote at Transformations ’22: artistic research in times of change, Luleå, The Swedish Research Council and Luleå University of Technology.

Haraway, Donna J., 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Durham: Duke Uni. Press.

Le Guin, Ursula K., 1989 (1986). “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.” In Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places, 165–170. New York: Grove Press.

Transgressing Boundaries: Reimagining Civic Institutions through Nomadic Architectural Pedagogy

Nadia Bertolino

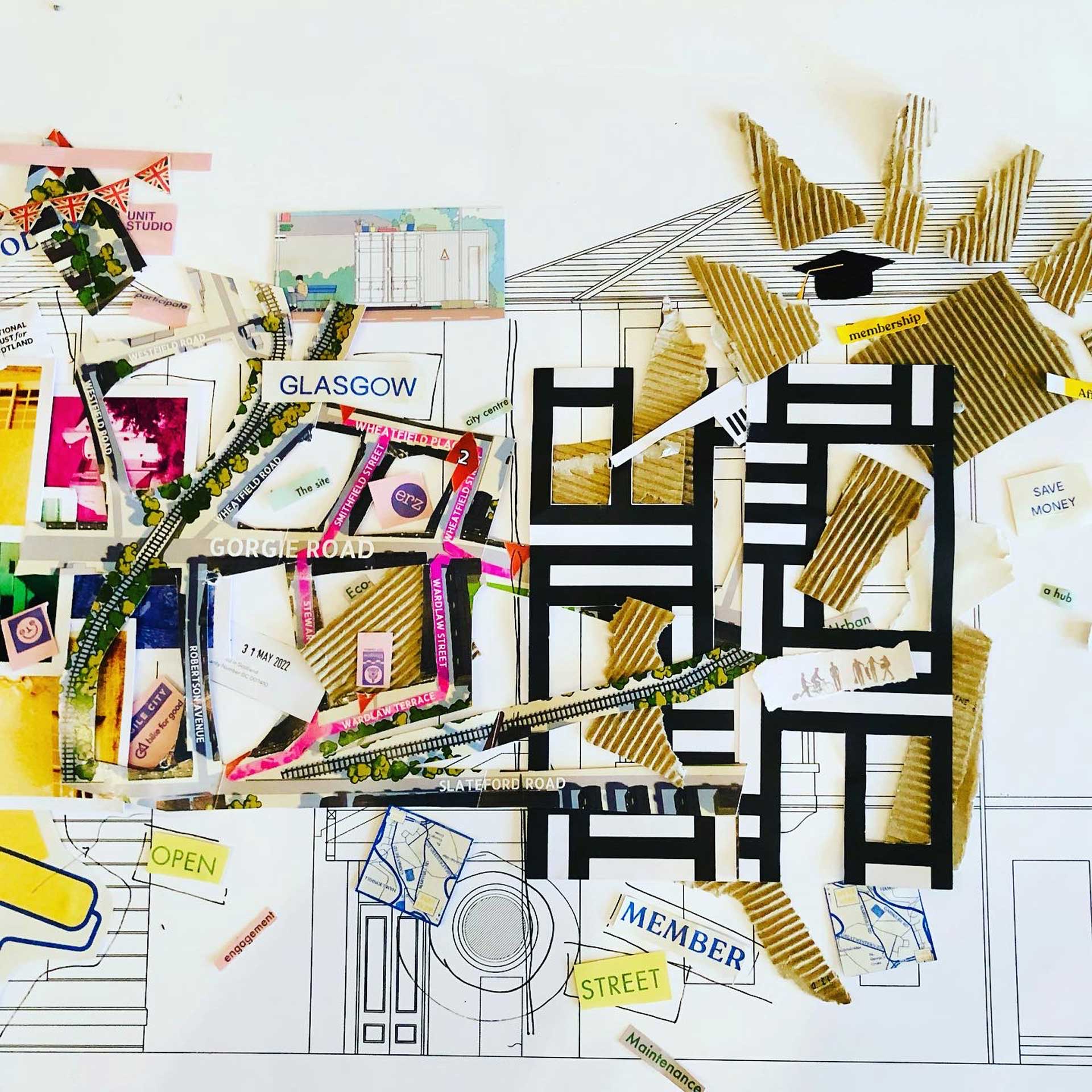

At 25 Prince Edward Street in Govanhill, Glasgow, four undergraduate students present their poster—a visual interpretation of what ‘civic infrastructure’ means in the local context, based on their recent experience of the city—to a group of peers and local residents. Photo: Nadia Bertolino (2022).

The exploration of nomadic architectural pedagogy as a critical framework for reimagining civic institutions presented a transformative opportunity to question and challenge dominant spatial paradigms. This approach gained significant traction during the Micro Civic Institutions of Care workshop, conducted in Glasgow in June 2022 with Year 3 BA Architecture students and educators from Northumbria University. The workshop interrogated the intersection between architectural education, spatial justice and collective urban engagement by foregrounding critical design pedagogy—a pedagogical model that actively critiqued power structures, disrupted normative practices, and empowered learners to co-create knowledge (Freire, 1970; hooks, 1994; Awan et al., 2011). This resonated with McEwan’s (2023) proposition that architectural pedagogy must engage with theory, critique, and typology as tools for addressing the ecological and social urgencies of the Anthropocene.

Moreover, the workshop’s methods aligned with feminist pedagogies that sought to destabilise entrenched hierarchies within architectural education. This pedagogical praxis insisted on situated knowledge and collective agency as critical tools for transforming architectural practice (Haraway, 1988; Lange et al., 2017). Such an approach contended that knowledge production must emerge from the embodied, partial, and often precarious experiences of learners and communities, disrupting the illusory neutrality of conventional architectural discourse.

By embedding architectural learning within the lived environments of Glasgow’s streets, the workshop dismantled the separation between theory and practice, challenging the traditional studio-based model. This position echoed Rendell’s (2007) call for interdisciplinary, site-responsive methodologies that foster new forms of spatial knowledge. Inspired by Cavart’s (1975) and De Carlo’s (1976) radical pedagogical experiments, participants engaged with the city as a site of learning—a notion that intersected with Livingstone’s (2019) vision of the arts of citizenship. Through this, the workshop not only mapped existing spatial injustices but actively generated micro interventions that challenged hegemonic urban narratives.

Workshop “Micro Civic Institution of Care,” part of the Year 3 BA Architecture study trip from Northumbria University to Glasgow. Students and local residents engaged in collaborative activities at The Kiosk. Photo: Nadia Bertolino (2022).

At the core of this methodological framework lay critical design pedagogy, which positioned architectural education as an instrument for exposing and contesting social hierarchies. This model built upon Freire’s (1970) conception of education as a dialogic and emancipatory process, in which the educator and learner co-constructed knowledge. The workshop adopted a horizontal learning model (hooks, 1994), dismantling hierarchical power dynamics and fostering mutuality among participants. This aligned with Krasny’s (2022) call for Scales of Concern—a paradigm that advocated for multiscalar design methodologies capable of addressing the interwoven crises of the present.

The workshop foregrounded feminist spatial practices as a means to challenge spatial injustices and foster intersectional inclusivity (Awan et al., 2011). The act of walking, observing, and collecting materials from the urban fabric positioned participants as situated agents within the city, inviting them to engage with its textures, sounds, and atmospheres. This embodied practice echoed Haraway’s (1988) assertion that all knowledge is inherently partial and contingent, dismantling the false objectivity of dominant architectural methodologies.

The valorisation of ephemeral urban practices within the workshop signalled a profound departure from the architectural obsession with permanence and fixity. Instead, participants were encouraged to generate temporary spatial interventions that amplified acts of care, solidarity, and subversion. Such a methodology resisted the extractive logics of neoliberal urban development, aligning with Salama’s (2015) call for pedagogies that nurtured reflective and inclusive architectural practices.

Through the creation of five scenario-collages, participants envisioned micro civic institutions that prioritised care, accessibility, and intersectionality over conventional infrastructural paradigms. These speculative collages destabilised dominant imaginaries of the city, inviting radical redefinitions of civic space. This speculative methodology resonated with Colomina’s (2022) advocacy for radical pedagogies—experimental approaches that dismantled the ideological foundations of architectural education.

The use of material play, assemblage and displacement blurred the boundaries between design and activism, echoing Petrescu’s (2007) articulation of relational architecture. By exhibiting the collages in the public realm in front of “Kiosk”, the workshop invited dialogue with passers-by, collapsing the division between designer and user. This gesture foregrounded the radical potential of temporary, co-created installations to engender democratic urban imaginaries (Lydon & Garcia, 2015).

Design concept developed by students in response to community-based infrastructures of care observed in Glasgow. Photo: Nadia Bertolino (2022).

Design concept developed by students, exploring soft structures of community-making in the city. Photo: Nadia Bertolino (2022).

The workshop’s focus on micro civic institutions of care signalled a radical reorientation of architectural pedagogy towards practices of maintenance, solidarity, and interdependence. In contrast to the spectacular logics of mainstream urbanism, the ethics of care privileged the often-invisible labour of sustaining life (Tronto, 1993; Akama et al., 2020). This redefinition aligned with Fitz & Krasny’s (2019) conception of critical care spaces—environments that nurtured vulnerability, reciprocity, and ecological stewardship.

By cultivating collective agency through co-creation, the workshop contested the increasingly commodified and individualised ethos of architectural education (Till, 2009). This participatory framework enacted hooks’ (1994) vision of the classroom as a site of radical transgression—a space where students learned to dismantle oppressive systems while imagining more just futures.

Design concept developed by students, exploring notions of public and private in Glasgow’s public spaces. Photo: Nadia Bertolino (2022).

The Micro Civic Institutions of Care workshop exemplified how nomadic architectural pedagogy could act as a powerful catalyst for reimagining civic institutions and fostering critical spatial agency. By embedding learning within the urban realm, the workshop dismantled the spatial and disciplinary boundaries that often constrain architectural practice. Through processes of material play, collective speculation, and situated dialogue, participants enacted feminist, inclusive, and ecologically attuned forms of urban engagement.

By foregrounding critical design pedagogy, the workshop cultivated radical imaginaries of care and spatial justice that contested the structural inequalities embedded in the built environment. Future iterations could deepen these methodologies by engaging with decolonial design practices (Escobar, 2018) and forging alliances with community-led initiatives. In this way, nomadic architectural pedagogy holds the potential to cultivate a new generation of spatial practitioners committed to fostering more just and compassionate cities.

References

Akama, Yoko, Sarah Pink, and Shanti Sumartojo. 2020. Uncertainty and Possibility: New Approaches to Future Making in Design Anthropology. London: Bloomsbury.

Awan, Nishat, Tatjana Schneider, and Jeremy Till. 2011. Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture. London: Routledge.

Cavart. 1975. Culturally Impossible Architecture. Workshop, Monselice, Italy.

Colomina, Beatriz, Ignacio G. Galán, Evangelos Kotsioris, and Anna‑Maria Meister, eds. 2022. Radical Pedagogies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

De Carlo, Giancarlo. 1976. ILAUD Workshop Materials. International Laboratory of Architecture and Urban Design. Unpublished workshop documentation.

Fitz, Angelika, and Elke Krasny, eds. 2019. Critical Care: Architecture and Urbanism for a Broken Planet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Freire, Paulo. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder.

Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599.

hooks, bell. 1994. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge.

Krasny, Elke. 2022. Scales of Concern: Architecture, Ecology, and the Politics of Care. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Lange, Barbara, Arnold Kalandides, Bernd Stober, and Ingo Wellmann. 2017. New Urban Spaces: Urban Theory and the Scale Question. London: Routledge.

Livingstone, David N. 2019. The City as University: Place, Identity, and the Spaces of Higher Education. London: Routledge.

Lydon, Mike, and Anthony Garcia. 2015. Tactical Urbanism: Short-Term Action for Long-Term Change. Washington, DC: Island Press.

McEwan, Cameron. 2023. “Architectural Pedagogy for the Anthropocene: Theory, Critique and Typological Urbanism.” Archnet‑IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 17 (3): 478–95.

Petrescu, Doina, ed. 2007. Altering Practices: Feminist Politics and Poetics of Space. London: Routledge.

Rendell, Jane. 2007. Art and Architecture: A Place Between. London: I.B. Tauris.

Salama, Ashraf. 2015. Spatial Design Education: New Directions for Pedagogy in Architecture and Beyond. Farnham: Ashgate.

Till, Jeremy. 2009. Architecture Depends. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Tronto, Joan. 1993. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. New York: Routledge.

Practices of Un—Learnings Through Feminist Spatial Conversations and Media Materials

Janna Lichter

Kaddi Wandaogo in conversation with Janna Lichter, 2024. Image: Janna Lichter.

Armine Harutunian-Mascia in conversation with Janna Lichter, 2024. Image: Janna Lichter.

Julia Nuler (left) and Miriam Kreuzer (right) in conversation with Janna Lichter (middle), 2024. Image: Janna Lichter

Najlaa Manout in conversation with Janna Lichter, 2025. Image: Janna Lichter.

Moving between the roles of teacher, researcher, and artist, I engage in conversational and audiovisual practices that initiate processes and spaces of un—learnings. As a teacher, I activate critical pedagogies and audiovisual engagements through conversational practices, as a researcher, I conceptualise artistic frameworks to produce alternative knowledges, and as an artist, I experiment with image-making that challenges dominant stereotyped narratives. The following text presents how these three approaches reinforce one another, introducing feminist spatial conversations and media materials.

I taught at the University of Applied Sciences Düsseldorf between 2023–24, where I shared my research on conversational practices as methods and methodology within the field of audiovisual media. The seminar invited students to reflect upon systemic inequalities in their everyday lives, and to explore how visual narratives might challenge dominant representations. It began with moments of irritation, as students asked themselves what the personal could mean and how it could make sense, yet over time this hesitation opened into conversations they cared about, which connected them to others. Through shared discussions and feedback sessions, we explored how to translate their personal experiences into experimental video and film formats. One project addressed the emotional dimensions and pressures experienced by a student in institutional contexts. Another engaged with her family’s history, with dialogues between her mother and grandmother from Togo. A third video centred on the intergenerational histories of Turkish guest workers in Germany. All these works demonstrated how students opened up and shared personal experiences, which connected them to broader questions through situated and contextualised inquiry.

The seminar showed how conventional education often fails to include knowledges grounded in embodiments, emotions, and lived experiences. In my research conversational practices emerge as relational and creative strategies that intervene in dominant pedagogical structures. In resistance & desire, published by bildungsLab*, a collective of Migrant Academics* and Academics* of Color working within pedagogical and cultural fields, Saboura Naqshband and Trovania Delille suggest that aesthetic education processes have the potential to engage in genuine communication and spaces for thinking in times of global crises and division (Naqshband and Delille 2025, 7-8). Alternative pedagogies and creative processes can challenge power structures and enable the transmission of other ways of knowing. This search speaks to my own desire to imagine educational spaces that nourish emotional and relational forms of un—learnings. I draw on bell hooks’ reflections on a School for Love—a place that does not yet exist, despite the urgent need to cultivate “care, affection, recognition, respect, commitment, and trust, as well as honest and open communication” (hooks 2000, 5). hooks frames education as a radical act of liberation, centring engaged pedagogy as a means to resist systemic oppression and build transformative learning spaces, arguing that education must be a practice of freedom, confronting supremacist ideologies internalised within traditional education systems (hooks 1994, 10). In this notion, I imagine a “School of Conversations” shaped by feminist practices of speaking and listening as acts of un—learnings. By navigating feminist knowledges, pedagogies, and intersectionality, I explore how image-making and feminist practices activate collective agency. My work contributes to building alternative pedagogical spaces proposing video-based conversations for multidimensional connections and transformative actions.

I work with conversation as both a method and methodology, interwoven through how I teach, research, and make images. It allows me to question dominant frameworks, shift perspectives, and create spaces where other forms of thinking and knowing can emerge. Positioned within intersectional feminist frameworks, I focus on interconnectedness, where structural inequalities are addressed through their entanglements. Nel Janssens describes conversations as methods of collective sense-making and dynamic processes of co-creation, where shared reflection and instruction become part of an open-ended feminist methodology, writing, “If we agree that conversations are more vested in experiences, we might assume that emotions, preferences, values and the personal form the natural base and direct resources through which a conversation evolves” (Janssens 2017, 151-156). In my work, I expand space through conversations for individual and collective self-representation. The conversations are not fixed outcomes or results, but develop as ongoing connections through the embodied experience of being in space together. These conversational practices produce and transmit knowledges across race, class, and gender, supporting collective struggles for empowerment and resistance.

As part of my ongoing Ph.D. research, I initiated a series of video-based conversations in collaboration with friends and academics with the title “Queer-Feminist Spatial Conversations” (Fig. 1, 2, 3 and 4). Drawing from my experiences as a teacher and researcher, I brought these perspectives into my artistic practices. My interest is to intervene in everyday environments through feminist spatial conversations, proposing open-ended prompts that allow conversations to follow their own rhythm within a co-created video-setting in everyday spaces. These conversations take place with people whose lived experiences are shaped by intersecting systems of oppression across gender, race, class, and sexuality, coming from diverse fields including architecture, economics, media studies, the arts, and pedagogies. The instructions include mappings of conversational principles, co-creation of video-setups, and multidiverse discourses, inviting participants to create meaning together, grounded in feminist, decolonial, and spatial concerns. Experimenting together with image and space functions here as a method of intervention, addressing systemic inequalities collectively and opening space for visual and spatial imaginaries.

The following examples highlight specific moments that unfolded through the self-organised conversations, shaping how we relate to ourselves and to one another through reflection, critique, and collective imagination. In conversation with Najlaa Manout (Fig. 4), a media and film analyst, we spoke about how female gazes often centre white experiences. We reflected on how we watch media for many reasons—to escape, to transcend, to dive into other worlds—yet find ourselves pulled back in the cycle of stereotyped and internalised images. Through our shared conversation, we un—learn dominant gazes and dismantle visual habits that shape how we see and feel. In conversation with Kaddi Wandaogo (Fig. 1), filmmaker and actress, we discussed the pressures of working within film industries and the racism in both production and casting. We shared our decision to pursue autonomy by telling our own stories. Kaddi described this as a “one-woman show,” working independently with accessible techniques and collaborative approaches rather than relying on large-scale industry structures. The conversation circled around the desire for creative choice and the need for support that exists beyond exploitative production logics. In conversation with Julia Nuler, architect and researcher, and Miriam Kreuzer, transformation designer and researcher (Fig. 3), we focused on friendship and the process of creating spaces within academia. We questioned how feminist practices can navigate different scales—small-scale as detailed, deep, and grounded acts of resistance—and how these connect to broader forms of structural critique to think concretely about building spaces of inclusion for feminist scholars and students within academic institutions. In the future this project will evolve into a growing platform for feminist spatial conversations, where knowledges circulate, grow, and intervene. A space that keeps conversations, connecting the personal and the political in shared meaning-making, shifting discourses on social justices and collective transformations.

While media representation exists within a hegemonic power matrix, authorities control meanings and reinforce hierarchical images and knowledges. Elke Zobl and Ricarda Drüeke examine feminist media production as ways of exchanging knowledges and alternative economies. They emphasise that feminist media practices have always turned to participation, activism, and social change, as they write “Using media to transport their messages, to disrupt social orders and to spin novel social processes, feminists have long recognised the importance of self-managed, alternative media” (Drüeke and Zobl 2012, 11-17). Across my artistic work, audiovisual fragments emerge as integral parts of the knowledges produced. Works that can stand on their own, as what they are, but at the same time, they also allow us to derive knowledges, refigure discourses, and actively participate in how meanings are produced. The feminist media materials that are developed collectively transgress dominant modes of media power relations and representations. They intervene in social contexts and media landscapes through ongoing circulations within these landscapes and within ourselves. These approaches commit to feminist activism and participatory production which feminist video-conversations serve as radical image-making and space-making for alternative acts of seeing and knowing.

By initiating seminars, lectures, and artistic projects around video-based conversations, I continue to build practice-based research that remains open and processual. These conversations are incomplete and open for critique, improvisation, and continuous negotiation. They invite researchers and non-researchers to build upon and expand these practices through feminist, artistic, and decolonial engagements. These artistic practices propose conversations as situated interventions into lived and urban environments, disrupting systemic inequalities through collective processes of un—learnings. In their continuous transformation, feminist spatial conversations open spaces for relational knowledges, intersectional imagination, and shared struggle. This work stays in movement, holding space for contradictions, for becoming otherwise, and multidimensional feminist futures.

References

Drüeke, Ricarda, and Gabriele Zobl. 2012. Feminist Media: Participatory Spaces, Networks and Cultural Citizenship. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

hooks, bell. 1994. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge.

hooks, bell. 2000. All About Love: New Visions. New York: William Morrow.

Janssens, Nel. 2017. “Collective Sense-Making for Change: About Conversations and Instructs.” In Feminist Futures of Spatial Practice: Materialisms, Activisms, Dialogues, Pedagogies, Projections, edited by Meike Schalk, Thérèse Kristiansson, and Ramia Mazé, 151–156. Baunach: AADR.

Naqshband, Saboura, and Trovania Delille, eds. 2025. Art that Cares: Kunst(pädagogik) als kollektive Fürsorge. resistance & desire #6. Berlin: Unrast.

from unstructured dialogues

Mudita Pasari and prachi

a note to the readers:

The following text has been modified for viewing on the Urgent Pedagogies platform, but an unaltered version (the best way to experientially read the paper) can be found here:

from unstructured dialogues (original)

The original essay, in its structure, uses an unusual writing and layout style in an attempt to translate the lived experiences of our unstructured dialogues- a dialogue with ourselves, a dialogue between the two of us and eventually the dialogue with the group at large. It is an experiment in writing for multiple ways of reading, reflecting this cross-learning and cross-pollination across the seasons- as we grew, learnt and adapted, but also safeguarded the unstructured-ness of the dialogues and the space itself. It is an attempt to articulate, to you as the reader, a glimpse of power OF space as practice, idea, possibility and play. We hoped that it can be accessed parallely or individually or sequentially for varying reader experiences, as a reflection of the experimental nature of the experimental learning space it speaks of.

This dialogue is a reflection in practice of a learning paradigm we have been experimenting with. ‘power OF space’ was a social experiment that we designed, positioned and placed outside the conforms of academia and co-nurtured with a small batch of co-conspirators. It has been two seasons of a series of unstructured dialogues hosted in spaces with apparent pluriverses to unpack the power OF space- with the emphasis on OF as attributing power and space not to holdings, possessions, or assets, but to processes of negotiation and collective emergence.

When we transitioned from spatial practitioners to novice design education facilitators; power OF space, gave us room to shed the rigid and performative boundaries of learning in an academic setup and explore alternative avenues for equity. To shed these uncomfortable identities we turned to what we knew best: space.

This experiment, in the interest of ‘commoning’ and creating ‘co’, became a ground for us to collectively explore a ‘learning-evoking-social’ space, where play emerged as the catalyst for eliciting ideas, for embracing vulnerability, and for humanising the interactions, and for truly beginning to perceive what learning outside academia would look like.

It started with a rebellion.

– albeit, small. Rebellion none the less.

So it was a very small rebellion, which led to an experimental project, and thankfully is continuing today

– Can we break out of institutions and learn at will and want?

What role does space play in all this?

pover OF space

We set a clear non-manifesto for ourselves, leaving space for dissent and debate among all co-learners –

Season 1

- We’re all co-participants and co-owners.

- There is no need for explanations or permissions.

- We come because we want to be there.

- We participate at our own will and comfort.

The only validation is from our own sensorial experiences and inquiry.

– Season 2

What we build, we build together;

what we decide we decide together; and

what we bring to our conversations, we own together.

Why do we need markers of learning or boundaries and hierarchies of knowledge?

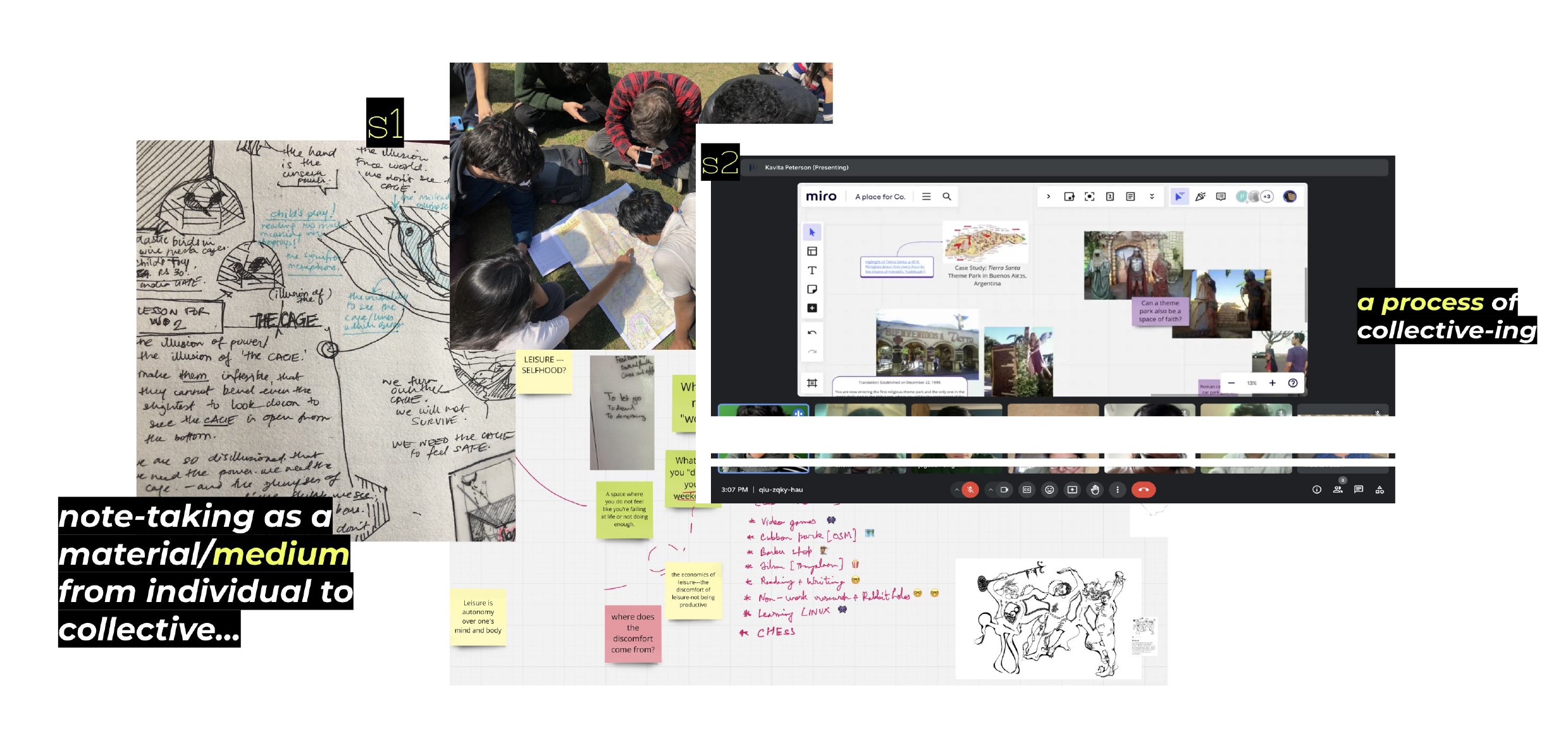

Season 1 (s1) was in-person and very physical.

The physical presence and the affordances of being together in time-space was core to pOs (power OF space) creating an impact. We inhabited spaces within reach in order to build a dialogue. power OF space would be ‘created’ as an experience and an equitable learning space each time we assembled as cohort at a site. While we took this appearance and disappearance for granted, it opened up different worlds each time we met and borrowed a little social place from our grounded surroundings.

Yet, there always lingered the question of what we would do once we met. What would drive dialogue, and what in the midst of all of this is knowledge? When we speak of learning outside of structures, are we even capable of perceiving this world, let alone dismantling it?

Ironically, this vulnerability is what became a grounding basis for equity in learning. Spatiality and free-flowing, scattered dialogue were key to commoning knowledge.

These spaces afforded us a basis for examining our individual experiences, and without simplifying the world into cause-effect, or learning into input, through power OF space, we found ways to acknowledge the complexities and interconnections through the relationships of experience which led us there and beyond.

an extended process learnt from season 1 in physical spaces…

The act and ability to cross international borders at drastically different places within India gave us behavioural insights into geo-political relations. Where the entry into Nepal, was a casual stroll across a barge; the border crossing for Bangladesh was under far more scrutiny and noticeably uncomfortable. This invariably led to a conversation and research into the relations between India-Pakistan as well, and in another thread, a dialogue on maps, cartography, contested territories and meaning-making.

power OF space, the Season 2 (s2) was translated and adapted to a different reality-entirely online. This constraint brought a new set of challenges, and opportunities.

What was only glimpsed in the feeling of a cohort in s1, could be perceived more clearly in the digital footprint of pOs s2. With the physical interactions, while dialogue broke structure, there was no collective imprint of that knowledge-making beyond the oral.

By going digital, pOs transcended time, space in multiple ways. It also transcended age. Crossing these restrictions, also meant being able to visually “table” our ideas for continuity. s2 grew a databank of common-ed knowledge and had the ability to visualise the ideas which in s1 remained within individual, unprescribed documentation. Knowledge and the process of collective meaning-making was evidenced (or had a digital footprint) within pOs beyond memory.

For example, crossing international borders in s2 came from geographical locations as well as identity. for someone from Australia, of a Fiji Indian identity to be able to find community with pOs. //So we’re talking a very different layer of understanding what it means to be Indian or part Indian//

The collective’s visually layered discourse on cross-border politics and identity pulled multiple examples into the database on migration and the design of cities, unpacking layers of who is a migrant, who is an immigrant, who is an expat? Who decides this and how are spaces designed or experiences to reflect on and concretise these ideas.

In season one, it was the body, which was sort of letting you go places.

In season two, it was the mind, which was going places.

However, though this landscape was new, even for season two, we had some non-negotiables. Some were carried forward from the non-manifesto, which arose post Season 1, from our reflections.

The online ‘hub’ for s2 needed to be many things in order for it to be an equitable space for non-linearity and non-hierarchy of dialogue and knowledge building;

The spatial typologies we chose varied in scale, in story, in formality and in agency of the flâneur. From an Art Fair, to a city centre rooted in its colonial history, to a religious cityscape, to border towns.

Without a precedent and by deliberately staying away from ‘academia’, this space of commoning grew from our own becoming- indulging our nature, being vulnerable and honest with our discomforts, while playing and encouraging play with our context, our selves and our knowledge. The elasticity of being able to push a space of learning beyond the rules we’d embodied in all our years was an exciting and dangerous freedom.

Learning is a form of collective placemaking, however transient.

At Varanasi and the India Art Fair, the power of the collective became a safety net for testing limits with authority.

The collective lent a different courage, it brought new meaning to a learning space but also elevated and empowered each individual within it to venture into their own unchartered territories, or questionable areas.

It was this collective placemaking of pOs where we could casually step across a cordoned-off “public” space at a private fair to picnic, reminding us of our place in the world, but also provoking us to challenge it. Learning spaces emerged from these collaborative acts of being subversive, making it easier to navigate grey areas or questionable spaces and be able to take ownership of space as ours.

One such account of learning came through the setup of situational prank which soured. While it dissolved boundaries between those facilitating and those participating; it led to reflections and dialogues on identity from this supposedly innocent act.

A set of students, much like us, the authors, wanted to break out of our set social roles within the ideas of institutional being. Together we brought s1 to life, willing it into being.

Each of us volunteered our time and our self to journey through these places, their experiences and to see where it goes naturally, without assuming or designing the outcome.

power OF space was thus essentially a set of dialogues that sat outside- conceptually, physically, and metaphorically- outside the limits of the university and the institute and their academic demands of curriculum, criteria, assessment, references, and deliverables.

A place for people to park their ideas week after week and in-between;

A place for play and light-heartedness that comes from being together- where people could maybe prank each other and /or play games;

A safe place- technologically, socially and emotionally.

A place for synchronous and asynchronous interactions, for incidentals and accidentals

A place for community

In order to build this hub which had to be many things, it also needed to be intuitive and as less tool-dependent as possible for us, and for all others to take to it rather than it becoming a hindrance.

We never had to deliberate over this placemaking in season 1, yet it is what would enable us to gate keep the non-manifesto- to remain true to the core idea and to what we cherished most from s1. This time, the ‘space of dialogue’ needed more backend design and intervention than in season 1.

However breaking non-linearities in dialogue is easier than breaking them in a digital medium. While we were ‘co’, we were also individual in our own spaces, and unlike the physical courage borrowed from a collective entity, we needed to invest in building the courage of power OF space.

One of our housekeeping suggestions was for everyone to keep their mic and video on at all times, and freely dive in and out of conversation. This would allow for each of our inhabited spaces to infiltrate our isolated, digital bubble, reminding us of our reality while making bridges across this space-time, but also encourage us to exploit the digital ability to dip into multiple parallel ideas at once.

And that is essentially being able to peek into each other’s world. But while I’m having a dialogue with you on an online platform, my brain is running to multiple other places being sparked by our conversation. So someone says something and I go open a tab and that tab leads me somewhere else.

Since we couldn’t find a singular digital application, pOs s2 hub would appear through a combination of applications each week. And as we spent time in building the data hub, or sneaking a peek into each others work collaborating in building a digital forest as our home, or maybe in the allocated hours of a video call we were able to navigate to build a democratic place of co. co-curated, co-owned and co-________.

note-taking as a material/medium from individual to collective…

It all started as a series of unstructured dialogues where we come with our lived experience.

How do we feel when we’re in a particular space? And how do we start to unpack this in terms of the poetics, the language, the representation, the sociopolitical relations, etc. Going to dialogues and places no one anticipated at the start including some hard conversations or conflicted territories.

The boundaries of these conversations only start to appear from the conversations and learnings themselves- what is uncomfortable for one, or collectively we don’t want to venture into…

Space was definitely a material, but then also the body and the senses, because going back to the defacto idea that lived experience is what matters. Because we happened to come from space design, that was our shared ecology, and that is what became a safe starting point for us, as experimenters. We realised that, as a medium, it could offer us the greatest potential for parity as well—because we’re always embedded in space, we could leverage it for dialogue.

And whether we’re talking with a non-designer or non-artist, it was the easiest way to start cultivating and perceiving learning outside of structures- having a common point of reference and of experience- malleability thus space.

What can we do to enable space,

to enable learners, to enable their lived experience,

to enable learning, to enable co?

——essentially it comes down to

how do we create a sense of co.?

And the co. translates in many ways.

Gröndal Bureau of Investigation

John Maclean

Gröndal Bureau of Investigation

Please visit the project site:

An Architectural Play for Learners

Johanna Gullberg

Based on understandings of the world that underline its materiality, architects are trained to imagine spaces by thinking, drawing, and modelling them. Exploring this ability of spatial imagination through interactions with other creative disciplines, architects may be presented with transformative learning experiences that can lead to changes of mindsets, as well as changes of built environments. One such other discipline is the theatre.

This text introduces a theatre play that emerged out of my doctoral thesis “Cogenerating Spaces of Learning: The Aesthetic Experience of Materiality and Its Transformative Potential within Architectural Education,” defended at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in Trondheim, Norway (Gullberg, 2021). It looks to how forms of learning that rely on making and participation in contexts outside the design studio can contribute to increased abilities for critical reflection on – and transformation of habits within – architectural education.

The central case study for the thesis was made during a semester-long master course held in the educational milieu Making is Thinking at NTNU in 2016. Making is Thinking joined forces with the theatre company Cirka Teater, known for physical theatre and spectacular urban interventions (Rødne & Gullberg, 2023), and concluded with the building of temporary indoor and outdoor structures for a festival at Nyhavna Harbour in Trondheim. I used an action research model for cogenerative learning to set up learning arenas, or dialogue spaces, in different phases of the course (Levin, 2014). In the arenas, I talked to fourteen architecture students about their experiences of learning at the crossroads of architecture and theatre.

Based on the interviews with the students as well as interviews with the theatre company, and the initiators of Making is Thinking, the thesis presents materiality and corporeality as two learning environment features that can contribute to deep learning. When I interviewed the founders of Cirka Teater about their creative processes, they accentuated relations between bodies and artefacts as key to their approach to spatial design. I was struck by the obviousness with which the performance artists spoke about the role of the body in the making of material spaces, while architecture students and educators were not used to talking about that theme. Many of the architects involved in the work at Nyhavna found it strange and uncomfortable to engage their bodies in design exercises, but the theatre company inspired them to push themselves into experimentation. The learners’ willingness to take risks was also supported by my introduction of dialogue spaces. By being invited to give words to sensual experiences of learning, the architecture students let those experiences sink in deeply. Reflections on practice expanded their repertoires as spatial designers.

Although enjoying crafting the layered composition of my thesis, I experienced how academic writing dampened, rather than revealed, the power of the exercises in the course. I nurtured a desire to share my research findings in a more accessible form than a monograph. From the investigations in my thesis, I knew that one must break professional habits in order to enter transformative experiences of learning. That is, if I were to walk my own talk, I had to take the risk that comes with writing in a new way, and I started experimenting with fictional variations on my prior conversations with Making is Thinking students. Supported by my editor César Reyes Nàjera (dpr-Barcelona), I processed those variations into a theatre play with an essentially spatial plot – an “architectural play” – where explanations and footnotes gave way to free associations and everyday phrasing.

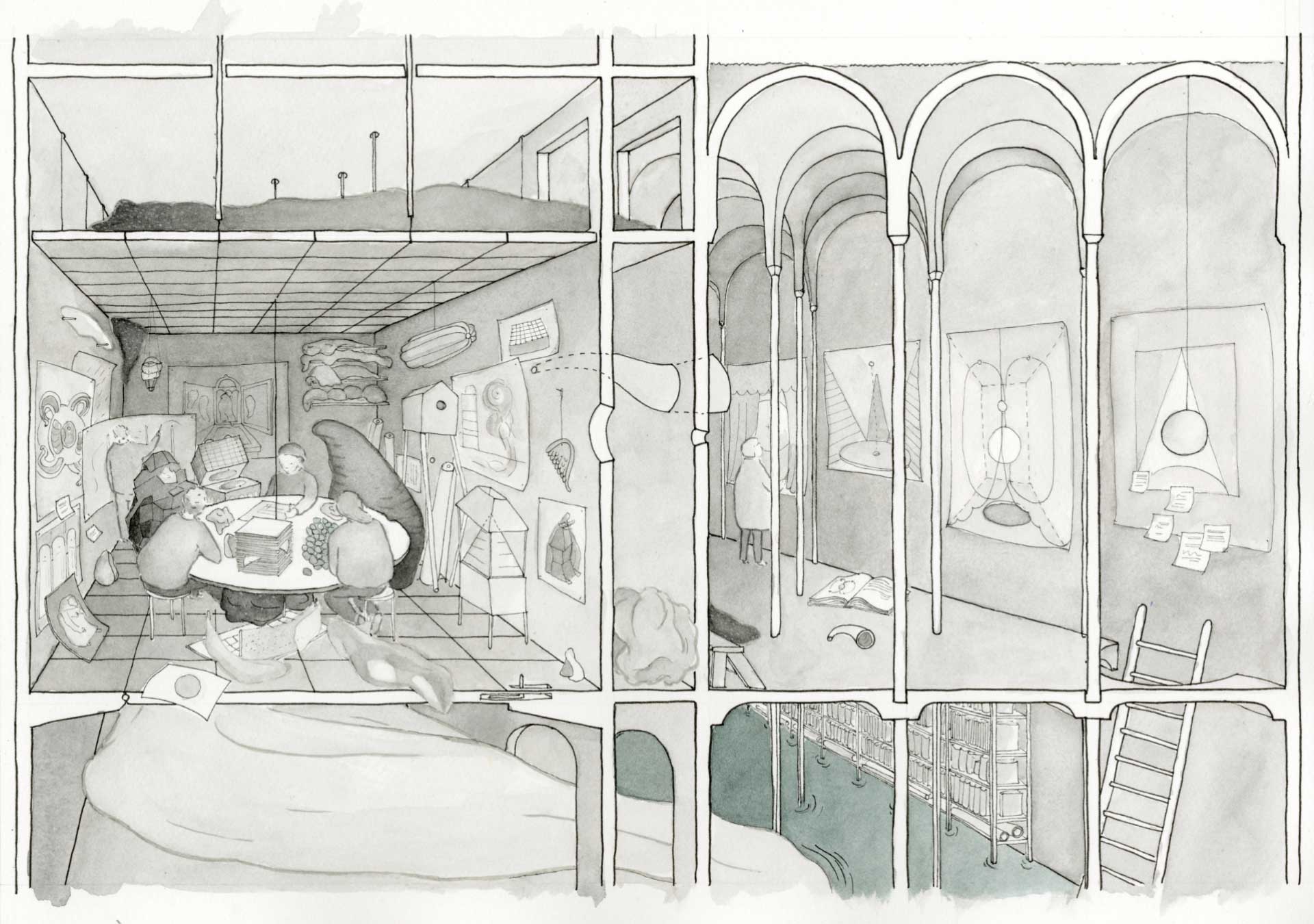

The play is a written dialogue in nine scenes. The atmosphere of each scene is conveyed through stage directions and mood descriptions. The play also includes a visual story in eight architectural drawings – plans, sections, perspectives, and axonometric views which may, or may not, inspire scenographic decisions.

Stones, nine squares, a plan. One of eight full spread drawings included in the play. Drawing: Johanna Gullberg.

Starting in a design studio (first act) and moving to an urban workshop space (second act), the play is set in evolving learning spaces inside and outside the architecture school, inside and outside given realities. The play begins when the protagonists Cyndyn and Alice enter class and whisper to each other:

CYNDYN

This is where we start, right?

ALICE

Yes, that’s what I’ve been told.

Cyndyn and Alice are architecture students who represent different types of learners. While he tends to resist change, she follows new acquaintances with an open mind. He strives for overviews and she sometimes loses her self – to a stone, for instance, or to a piece of fabric. And then, of course, their traits change as the scenes in the play unfold.

Cyndyn and Alice enter a semester run by Professor Kokoaja, or Koko, an architect and educator going through a mid-career crisis. Koko is known for dressing in clothes that express her architectural longings. Her signature work is a series of collage dresses that architecture students can wear to understand structural principles. Now, however, she is fed up with architecture and no outfit or theory will hide her agony. She therefore invites the performing artist Monsieur Farfel to teach together with her, hoping that he will bring new ideas. In the eyes of rigid architecture students, Monsieur Farfel is a somewhat crazy figure.

As the play progresses, nonhuman actors – like a whispering drawing and a model of a nightmare – come alive and entice Cyndyn and Alice into new ways of thinking and making.

Models and model-makers gather around a table while a researcher analyses their actions. One of eight full spread drawings included in the play. Drawing: Johanna Gullberg.

The drawings in the play operate as conversation pieces, stemming from my habit of sketching while writing. They are grounded in established conventions for architectural drawing but depict processes of change, although they may disturb some readers who prefer to let words alone inform images inside their heads.

Architect and illustrator Nina Eide Holtan gave me some advice on the drawings. Looking at them, one may discover variations of a diagram. It is the diagram of the mentioned cogenerative model for action research, with the learning arena as a central circle. Repeatedly drawing this diagram during my PhD studies enabled me to develop the action research model I was using, tailoring it for educational environments where architects and other aesthetic practitioners are trained, and where materiality is central to how learning happens. In the drawings presented alongside the dialogue in the play, the circle is repeated in different forms – as a concrete table to gather around, as a bodily organ, as a pendulum that sets lines in motion. With concepts from architectural theory in mind, I drew circles as spaces of crisis or gaps in the given, as cleared spots for continuous conversations and new beginnings.

The play, as with the thesis, deals with material spaces of learning with a transformative potential. The word potential is essential here. It points to one of the main findings in the thesis, namely that learning spaces ought not be set up to change learners in any given direction, but with the intention to enable them to enter and critically act in states of uncertainty and risk, where ethical, political, and social dimensions of material space are acknowledged. The relatively short and illustrated play can hopefully function as a “shortcut” into such complex themes. While the thesis contextualises the case study in Trondheim by drawing on theories and examples from the fields of education, theatre, and architecture, the play is a more direct and accessible instruct for experimenting with material learning spaces in becoming. Its temporary spaces and fictive characters allow for testing out new or unfamiliar tools and perspectives. Yes, one function of a theatre play for architecture students and educators may simply be to provide an opportunity for them to step outside of their habitual positions, engage in dialogue, and then return to work with renewed perspectives.

References

NTNU Open website with Gullberg’s doctoral thesis “Cogenerating Spaces of Learning:”

https://ntnuopen.ntnu.no/ntnu-xmlui/handle/11250/2740718

Rødne, Gro & Gullberg, Johanna. “Hvorfor er det åpenbart å samarbeide med et teaterkompani i arkitektutdanningen? Seks svar” (“Why is it obvious to collaborate with a theatre company in architectural education? Six answers”). In Cirka 40 år med teater: En historiefortelling og en teaterantologi, edited by Stein Arne Sæther. Cirka Teater, Trondheim, 2023, 224–231.

Levin, Morten. “Co-Generative Learning.” 2014. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Action Research, edited by David Coghlan and Mary Brydon-Miller. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd, 109–112.

Gullberg, Johanna. “Cogenerating spaces of learning.” 2024. Urgent Pedagogies website:

https://urgentpedagogies.iaspis.se/cogenerating-spaces-of-learning/

Up Side Down Inside Out Educational Surrounds: Learning from Arakawa and Gins’ Architectural Absurdities

Sylwia Janka Poltorak

Arakawa and Madeline Gins, Critical Resemblances House, Site of Reversible Destiny—Yoro Park, Yoro, Gifu Prefecture, Japan, 1993-95. Photo courtesy of the Sites of Reversible Destiny Yoro Park. © 1997 Reversible Destiny Foundation. Reproduced with permission of the Reversible Destiny Foundation.

This essay explores the concept of absurdity and playfulness as design tools for the built environment, specifically in the field of spatial design education. By challenging traditional definitions of architecture, the work draws on the theories of Shusaku Arakawa and Madelina Gins (A+G) who argue that architecture should actively engage the human body-mind to foster cognitive and motor development. Using the concept of absurdity, spaces are designed to provoke thought and facilitate learning experiences. The study emphasises the importance of sensory engagement and embodiment in educational environments, while technological advancements lead to increasingly screen-based interactions and diminished role for physical engagement. As the essay argues dynamic and playful environments not only enhance learning but also contribute to human well-being and longevity. Procedural architecture and philosophical concepts such as pataphysics are explored.

The contemporary educational landscape, especially in fields such as spatial design, would benefit from innovative approaches to stimulate and enhance cognitive and motor performance among the learners (Barsalou L. W. 2008) “Up Side Down Inside Out…” explores the potential of speculative unorthodox learning environments to significantly improve the learning experience. Such environments are not only expected to improve the well-being of learners, but also to foster enhanced social interactions in post-education events, particularly in a world increasingly challenged by economic, social, and demographic crises, to name a few. (Seamon 1979, 96)

At the core of this investigation is the work of Shusaku Arakawa and Madeline Gins (A+G), the founders of Reversible Destiny (RD) who stated that architecture is actively involved in the formation of the human, influencing their behaviour and perception and that it exists in the service of the body. (Arakawa and Gins 2002, vi)

In the context of architecture, “absurdity” refers to a deliberate departure from conventional logic, norms, and expectations in design. It involves creating spaces that surprise and challenge traditional ideas of what architecture should be. By using absurdity as a tool, architects can deny practical functionality and/or standard aesthetics, and they can design and create spaces that are not only functional but also thought-provoking. Such spaces facilitate a deeper engagement with the surrounding and a greater awareness of the possibilities of architectural expression.

Architects who embrace absurdity, following A+G, can design environments that push the boundaries of what is considered “normal”, encouraging occupants to question their knowledge on space, form, and function. This challenges both the designers and the learners to step outside their comfort zones and engage with space in a more meaningful way. This can be seen in the Reversible Destiny projects – spaces deliberately designed to be disorienting and challenging the relationship of the body-mind with the built environment.

A+G, architectural interventions appear as powerful examples to disrupt the monotony of conventional architectural standards, like these proposed by German architect Ernst Neufert, famous for his organisation of standardised measurements for design and architecture in Architect’s Data. This disruption is not merely for the sake of novelty, but is rooted in the belief that such environments can foster and nurture heightened sensory engagement, curiosity, and mindful interaction with the surroundings. Such embodied learning is crucial for multi-level learning and shall be desired in breeding new generations of not only spatial designers, but people acquainted with the surrounding and aware of the agency of their body-mind in general.

In today’s digital age, where screen time and sedentary lifestyles diminish sensory engagement and may lead to cognitive and emotional limitations, there is an urgent need for embodied learning environments. David Seamon’s A Geography of the Lifeworld highlights how phenomenological connectedness between people and place is vital, while neuroscientific research by Lawrence Barsalou shows that our cognitive processes are deeply intertwined with bodily states and sensory experiences. This supports the idea – central to A+G of the architectural body – that the environment actively shapes human experience rather than simply serving as a backdrop. (Arakawa and Gins, 2002, 39-47)

Arakawa and Madeline Gins, Site of Reversible Destiny—Yoro Park, Yoro, Gifu Prefecture, Japan, 1993-95. Photo courtesy of the Sites of Reversible Destiny Yoro Park. © 1997 Reversible Destiny Foundation. Reproduced with permission of the Reversible Destiny Foundation.

Procedural architecture became a core for all the Reversible Destiny projects. It is a process-oriented, psycho-corporal approach that examines how the built environment and the human body influence each other, continually shaping and expanding one another’s possibilities. (Keane 2011)