Learnings/Unlearnings: Material Community Practices

Nicola Antaki, Pia Palo, Marco Adelfio, Emilio Brandao, Effrosyni Roussou, Eeva-Maarja Laur, Sadia Sharmin, Ziana S. Madathil, Zuzana Tabaková

CATEGORY

Welcome to Learnings/Unlearnings Reader #4: Spaces and Places of Environmental Learning: Material Community Practices guest edited by Nicola Antaki, Emilio Brandao and Meike Schalk. The Reader includes contributions from the section “Building and Playing: Spaces and Places of Environmental Learning” from the conference Learnings/Unlearnings: Environmental Pedagogies, Play, Policies, and Spatial Design, which took place in Stockholm in September 2024.

The contributions in Reader #4 focus on a variety of methods used to instigate, plan and sustain environmental learning practices and pedagogies. The Reader explores environmental learning as a practice of care, bringing together authors who examine how care is embedded in the tools we use—and the ways we plan and design those tools—to support meaningful environmental engagement. They also ask: How do the methods we choose shape the kinds of learning that emerge? What positionalities, assumptions, and relationships become visible through these methods? How might we navigate and address the tensions and power dynamics that arise? The papers also consider the many roles played by participants, designers, researchers, and educators, and invite us to rethink and adjust these roles in light of the challenges and possibilities of future practice. Together, these contributions encourage us to reflect critically on what it means to learn with and care for our environments, and how our collective efforts might cultivate more just and resilient ways of knowing and acting in the world.

In the first paper “Co-design Tools as Boundary Objects”, Nicola Antaki explores the elements necessary for sharing across communities of practice (Wenger 1999) in two environmental learning projects on the edges of institutions. The first takes place in Mumbai with NGO Muktangan schoolchildren and teachers and the Mariamma Nagar informal settlement (2012-2021) and the other in Saint Denis, Paris, with La Courtille Middle School year 7 students and staff (2022-ongoing). The paper focuses on collective encounters – using the concept of boundary objects (Star and Griesemer 1989) – in each case as site-specific tools for learning, (co)designing, sharing and commoning in situated pedagogies. In each case the boundary object reflects the local material culture in some way – through an embroidered tapestry in Mumbai, to the soil of a school vegetable garden in Paris.

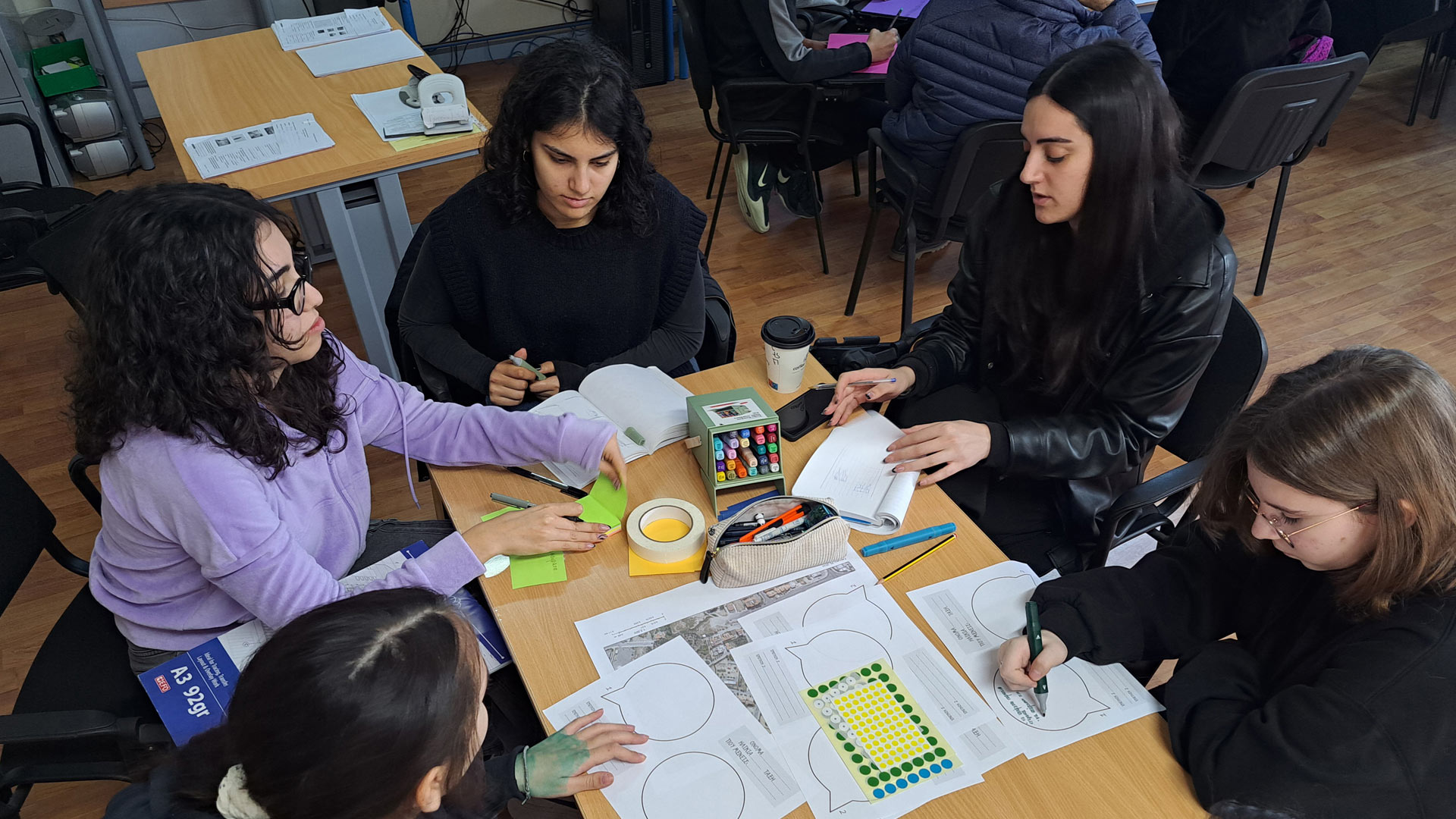

In an investigation of shared vocabularies, “Sharing Practices Workshop”, Pia Palo, Marco Adelfio and Emilio Brandao explore a workshop method that aims to understand a local vocabulary connected to practices of sharing and circularity in Hammarkullen, a late modernist suburb of Gothenburg in Sweden. Collectively, with a group of residents and local actors they investigate potential futures for sustainable practices in a specific context. Conversations centred around the meaning of circularity and sharing in Hammarkullen today prepared for the creation of speculative storylines. A conclusion evolved in a gathering of concrete ideas on possible hands-on actions within the specific conditions of Hammarkullen. Palo et al. recognise the strength of this method in its potential to root abstract concepts in local vocabularies and lived practices, building onto existing networks and local knowledge rather than trying to prescribe preexisting solutions and systems.

The contribution “Community-engaged Design-build Pedagogy Of and For the Commons” by Effrosyni Roussou discusses a pedagogical method and practice based on the consideration of the context in order to renegotiate architectural education’s hegemonic influences and implications. Set in a suburb of Nicosia in Cyprus the paper focuses on the “cocreation studio” of the University of Cyprus, that attempts to create impact in the way architecture students and local communities relate to and care for urban space through community-engaged design-build activities. Commoning is seen here as an everyday activity of managing shared resources such as spaces, knowledge and skills. Part of the live education experience of the studio is role-shifting to reconfigure both how students learn and how they transform their ability to relate to other agents in urban space.

Eeva-Maarja Laur’s contribution focuses on the transformative potential of a community self-building renovation. Laur explores, in an ethnographic study, a community‐led initiative in Denmark which redefines building renovation as an act of cultural and environmental regeneration. Rather than simply replacing old materials, the project harnesses them as part of the atmosphere bringing a place to life through sensory experiences: the cool drafts of spring, the tactile coldness of clay plaster, and the dialogic reciprocity of historical and modern architectural elements. The project demonstrates that renovation, when approached as a process of unlearning and relearning, can reconnect communities with their heritage and reshape their future environment. This perspective calls on architectural pedagogy to go beyond technology and to embrace holistic, experiential, and community-based tactics in renovations.

Sadia Sharmin’s paper “Learning With and From a Slow Garden” invites the reader to the suburb Tynnered in Gothenburg, Sweden, to explore a garden and its activities that have been self-initiated and curated by a mother and a son living in the neighbourhood. Sharmin employs the concept “caring curation” to address informal environmental learning beyond institutionalised structures. Through her method of visual storytelling she aims at foregrounding the making and keeping of the garden by a community of neighbours, mostly parents and children in an otherwise stigmatized neighbourhood, as a story of empowerment and pride. Sharmin argues that the capacity to imagine and enact change starts with small acts of care, not grand gestures and that spatial practices rooted in trust and collective responsibility may have the power to turn marginal spaces into sites of possibilities.

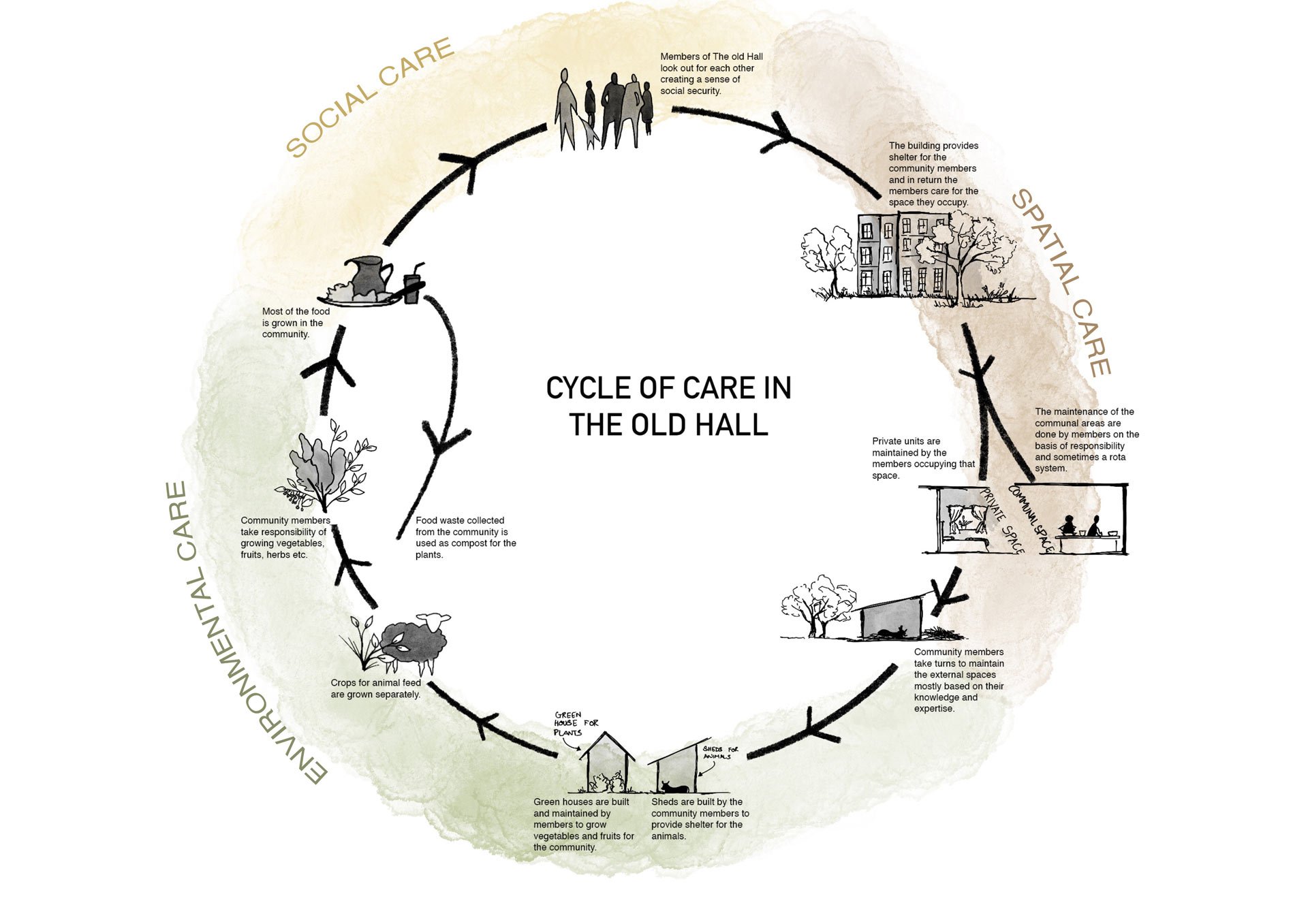

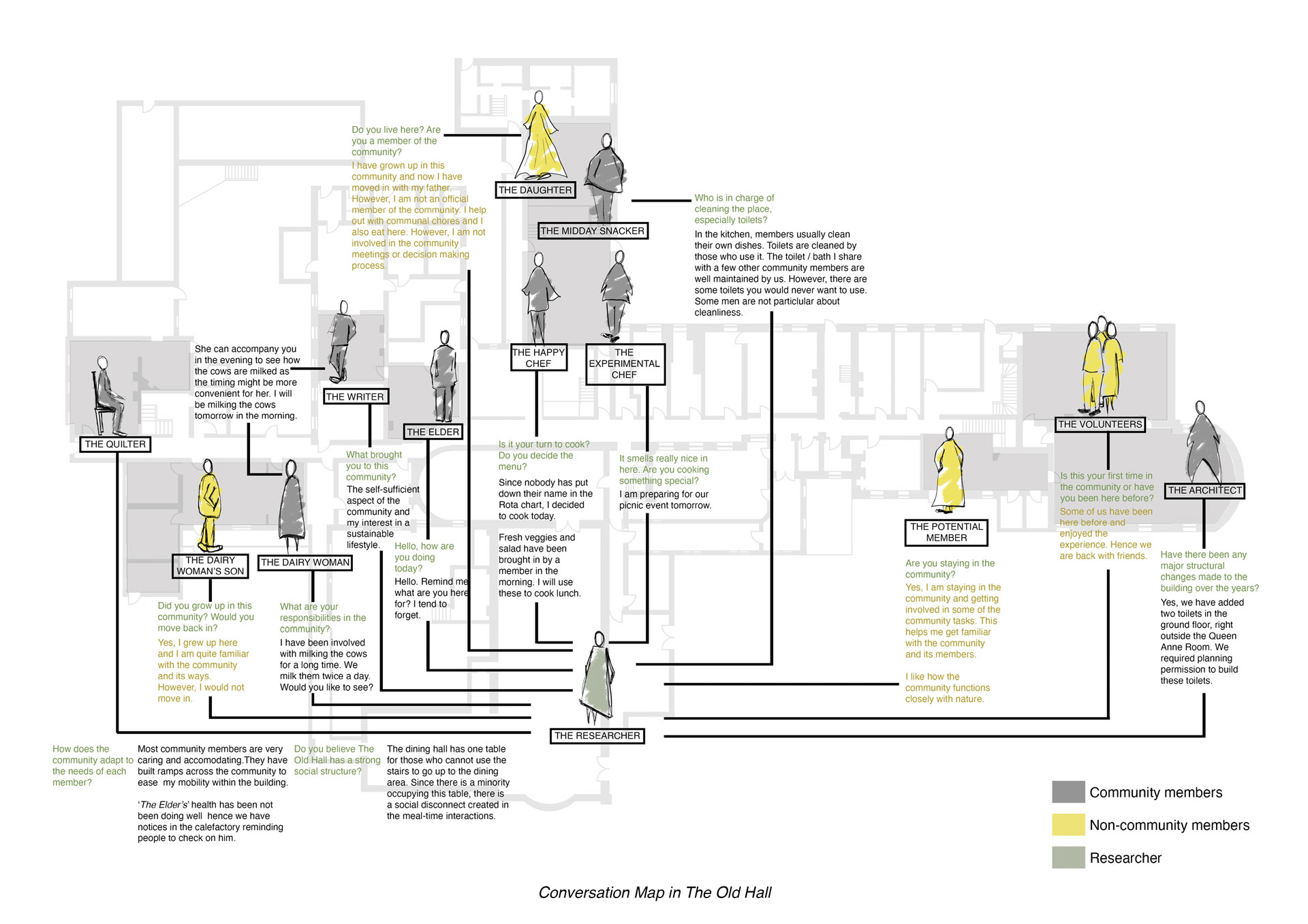

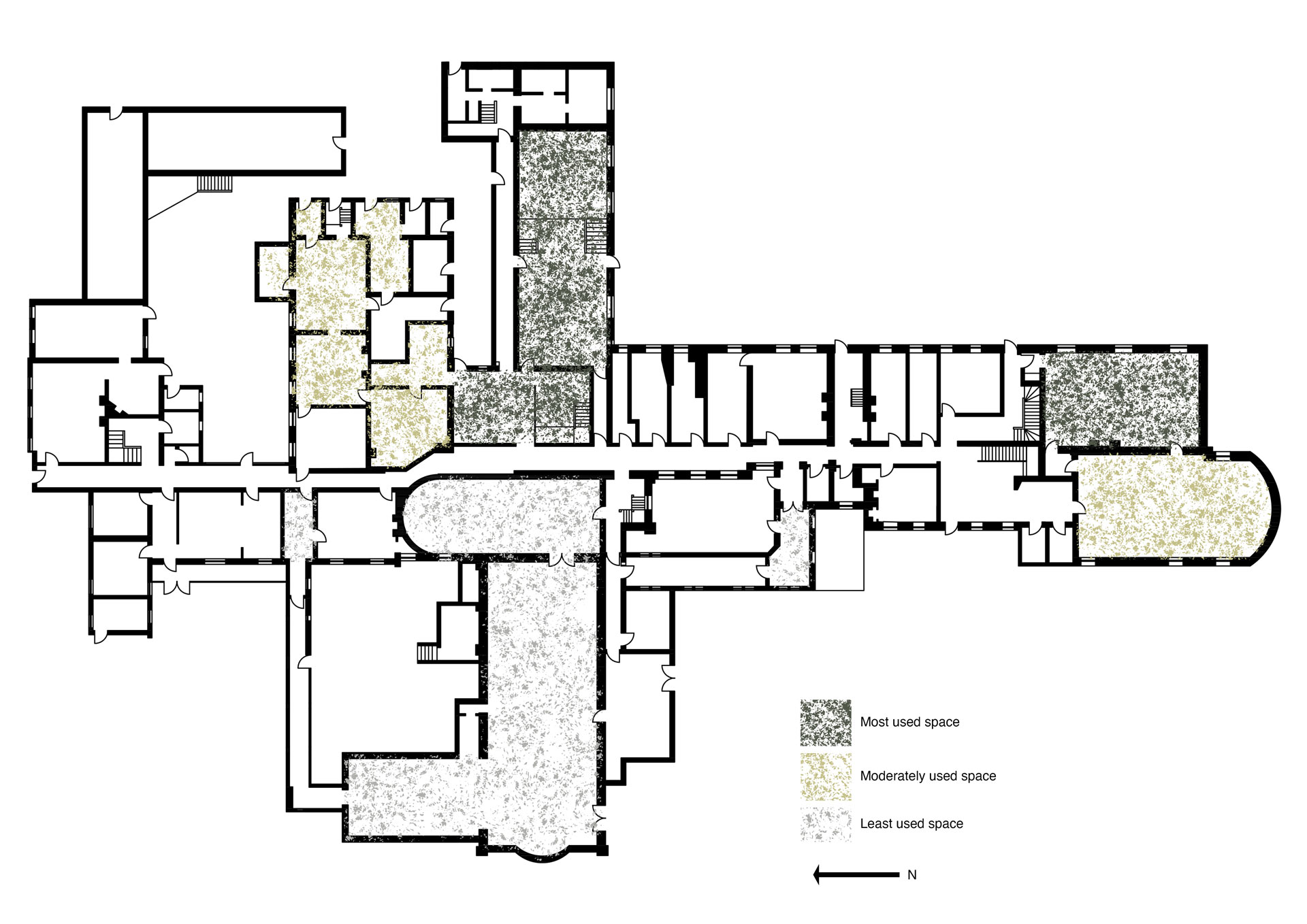

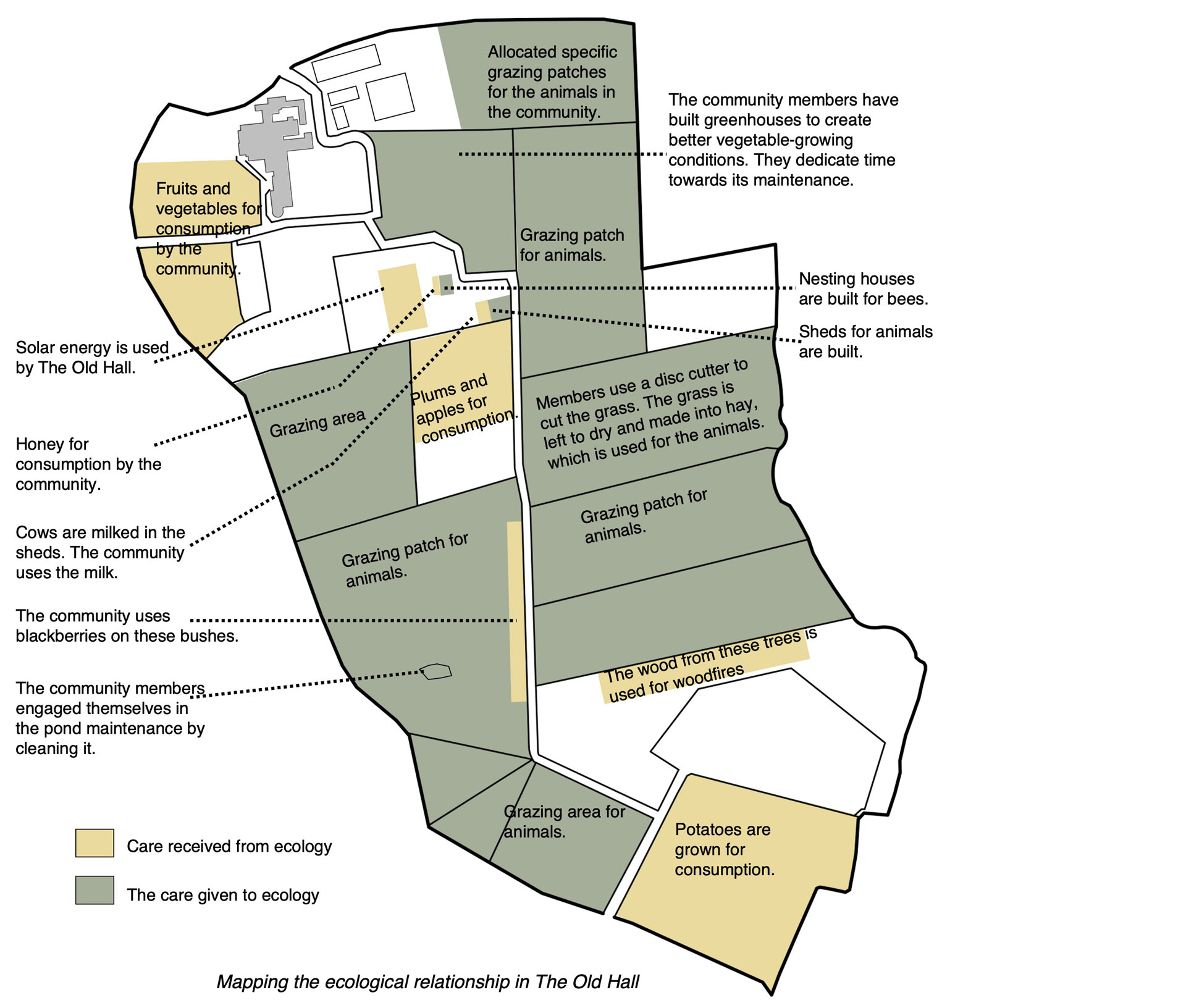

Ziana S. Madathil contributes to the exploration of care by investigating “practices of care and ecology in an intentional community” at The Old Hall – a community living in the United Kingdom. She identifies three caring types – social, spatial and environmental – caring practices such as sustainable ways of living and using ecological practices to reduce carbon footprint, but also as tools for commoning, sharing resources and knowledge. A part of her empirical research is discussed using drawings, diagrams and maps, showing the inhabitants’ practices of care and their associated spaces, in a bid to assess the spatial influence on communal life. Madathil argues that there is a vital relationship between human and non-human members of the community, and that it is an important setting to learn to care collectively and work towards ensuring ecological well-being.

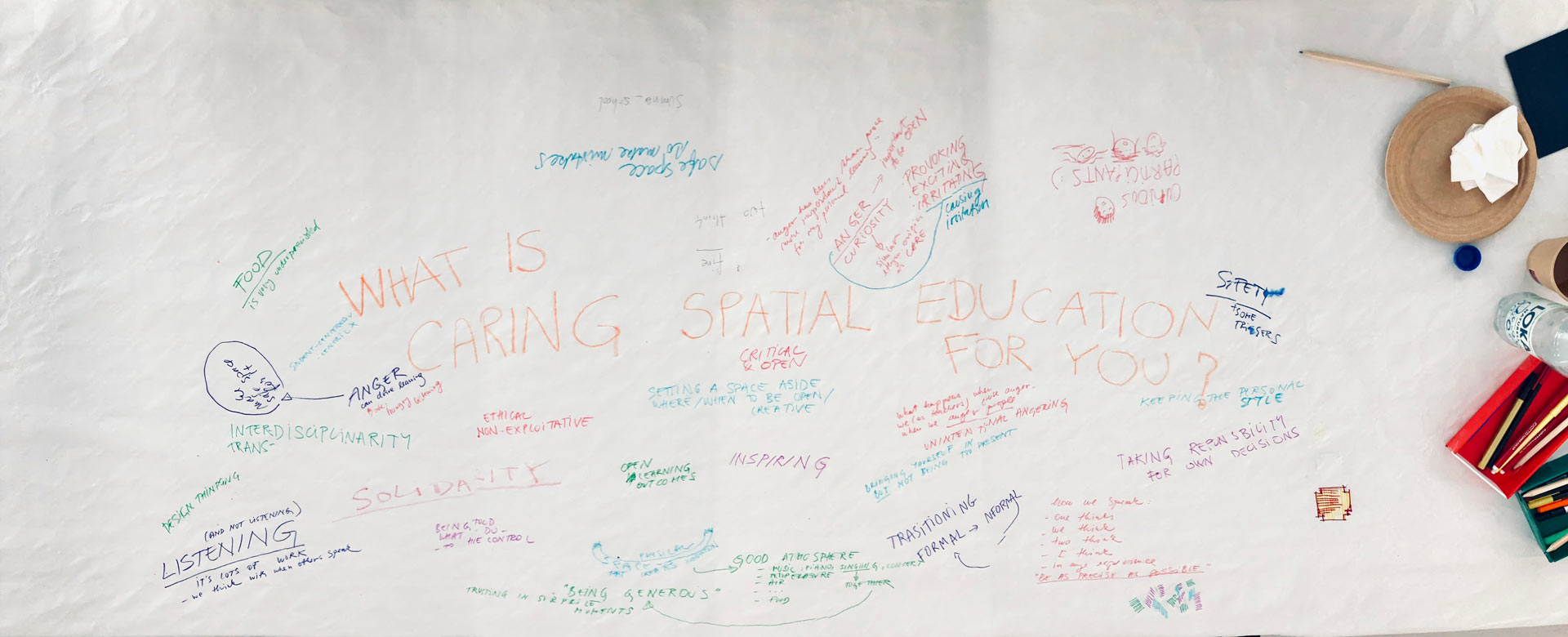

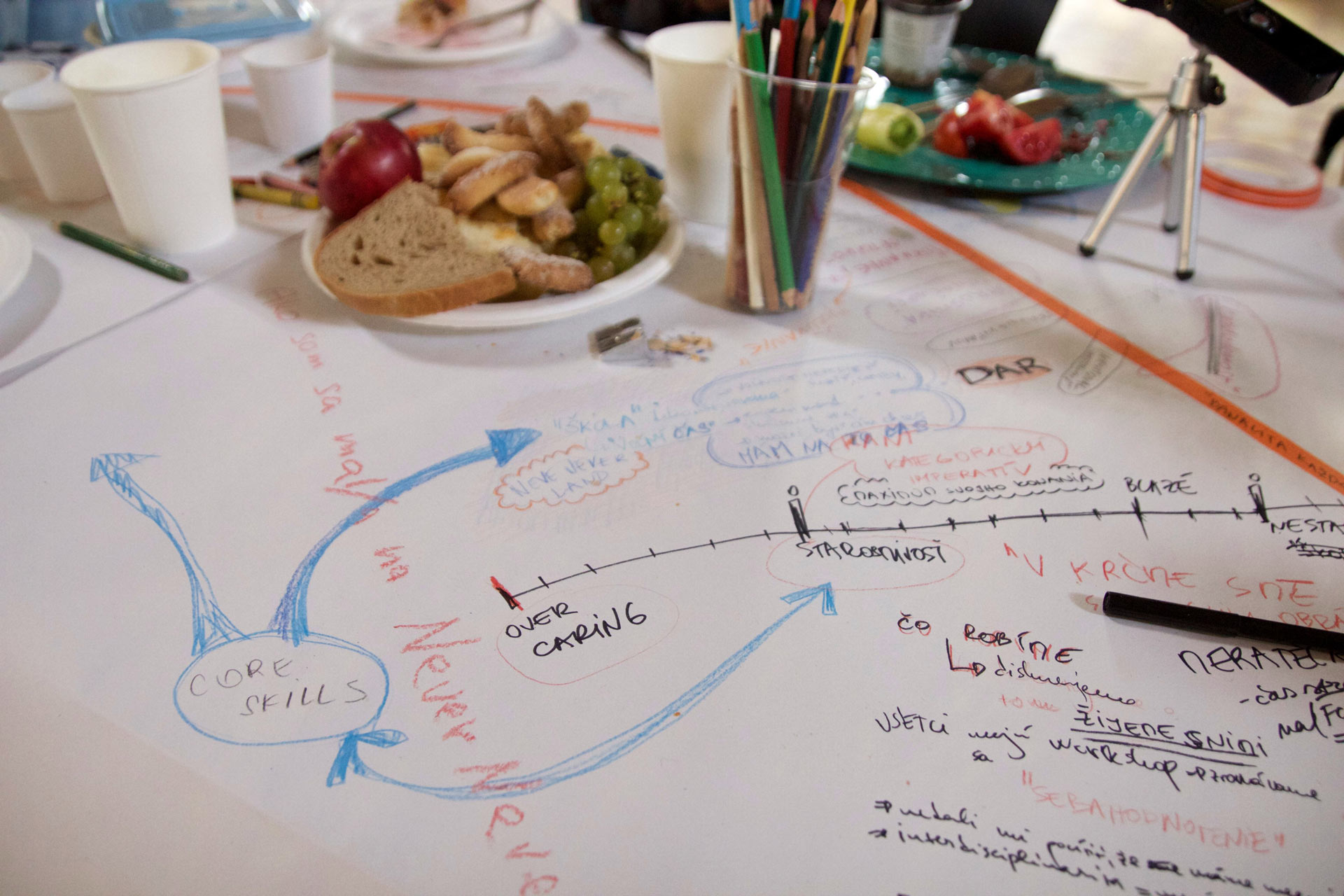

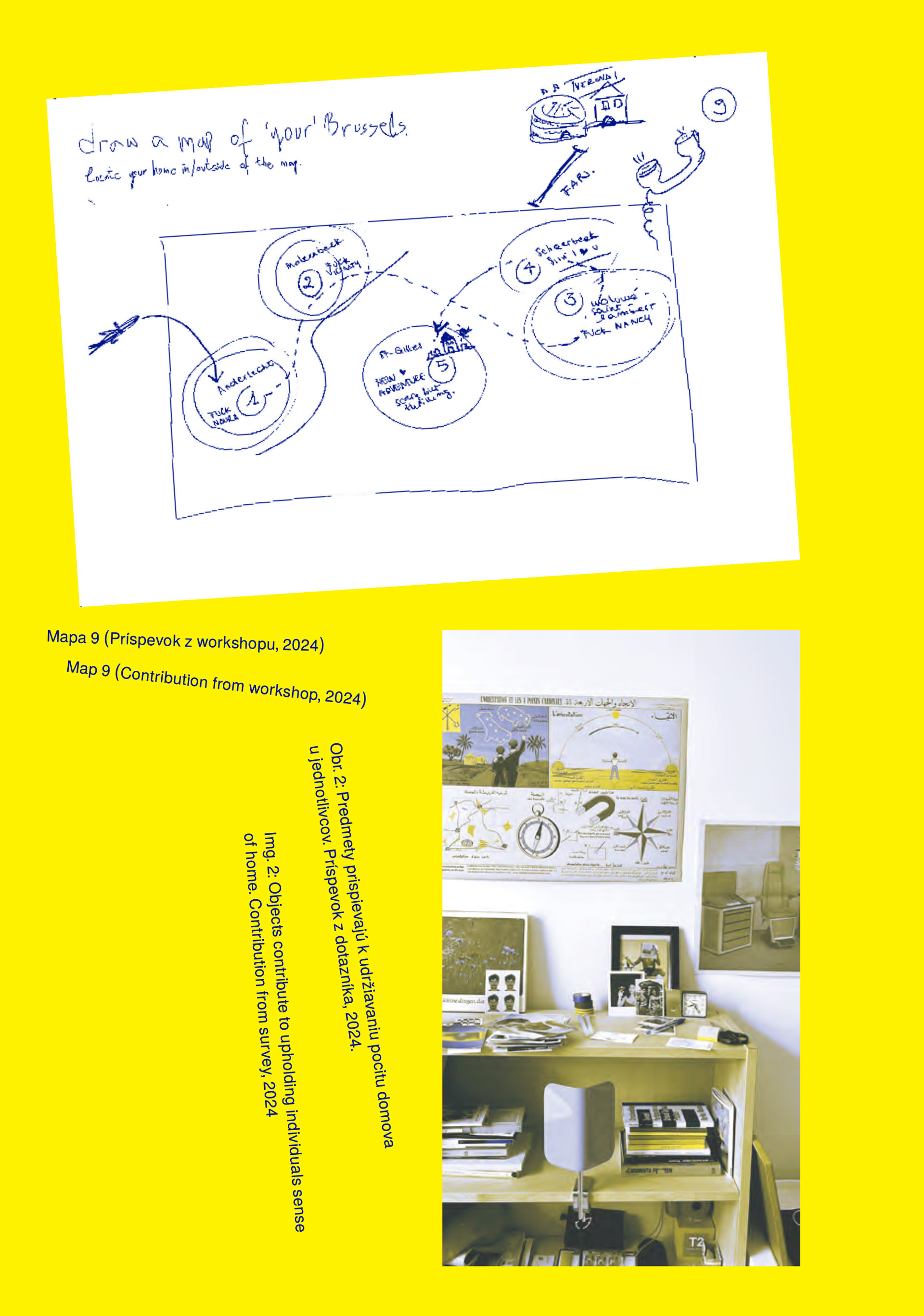

The paper “What is a Caring Spatial Education for You” by Zuzana Tabaková, Spolka gathers 18 workshop formats that the group has developed in four editions of their “Never Never School”, in Košice, Slovakia. Since 2018, Spolka, a group of sociologists and architects, has brought together multiple actors such as young professionals, city administrators, planners, interest groups and concerned citizens around urgent planning issues in public workshop formats and conversations. The gatherings emerged from a need for dialogical learning and research about cities. They served as possibilities to speculate and imagine together situated utopias for the city marked by former utopian modernist visions of the socialist regime. Ultimately, the Never Never School aims at raising awareness among local actors to collectively understand the city and create a space for a caring spatial education.

Contents

Co-design Tools as Boundary Objects in Civic Pedagogies in Paris and Mumbai

Nicola Antaki

Civic pedagogies are types of reimagined learning concerned with, and situated in, the environment. They are kinds of socio-spatial critical pedagogies (Paulo Freire 1970, 1974; Henry Giroux 2010) that are place-based (David Gruenewald 2003). In a civic pedagogy, learners can develop a sense of critical consciousness by exploring and understanding their social and physical contexts. The city, or the material world, serves as both the site of learning and a means for learners to realise their agency. It also provides a framework for critically reflecting on one’s place in the world. Through the situated practice of civic pedagogies, learners engage with the social and physical challenges of their communities and take action to address them (Antaki, Belfield and Moore 2024).

Civic pedagogies can be learning experiences that occur both within and beyond the boundaries of traditional schools, engaging young people in shaping and interacting with their urban surroundings, through design, management, or the creation of their environment. These practices are rooted in real-world contexts, where learning happens outside the classroom and places a strong emphasis on the physical environment as the central space for education (Antaki, Belfield, and Moore, 2024). Often, these pedagogies involve alternative alliances (Tan 2021), unusual relationships of differing communities of practice (Wenger 1999), such as designers as facilitators and students as designers.

To do this, civic pedagogies often use boundary objects (Star and Griesemer 1989) as tools for learning, (co)designing, sharing and commoning. Here, I want to discuss the characteristics of the boundary objects crafted in two civic pedagogies: the first, a collective design practice with NGO Muktangan School students and the Mariamma Nagar neighbourhood in Mumbai (2012-2021); and second, the co-design of an EcoLab (an ecological laboratory) with La Courtille Middle School students and the local neighbourhood in Saint Denis, Paris (2022-ongoing). Both these projects locate their radical classrooms (bell hooks 1994) outside institutional walls, in the built environment, as a situated pedagogy. What boundary objects are necessary for the development of these civic pedagogies?

The boundary object is an analytic concept introduced by Leigh Star and Griesemer in 1989, describing objects that:

inhabit several intersecting social worlds (a terrain, species, habitats, etc.) and satisfy the informational requirements of each of them. Boundary objects are objects which are both plastic enough to adapt to local needs and the constraints of the several parties employing them, yet robust enough to maintain a common identity across sites.

—Star and Griesemer 1989

The concept is of use here to help identify and analyse the objects or tools that enable communities of practice (Wenger 1999) to crossover, sometimes sharing understandings, other times enabling diverging understandings, always enabling knowledge production. Star emphasises that the term ‘boundary’ implies an edge or periphery but that ‘it is used to mean a shared space, where exactly that sense of here and there are confounded. These common objects form the boundaries between groups through flexibility and shared structure – they are the stuff of action.’ (Star 2010)

She also specifies that boundary objects ‘allow different groups to work together without consensus.’ In civic pedagogies these types of objects are essential for allowing diverse voices to be heard equally, and power to be shared. Etienne Wenger built on the boundary object concept, identifying them as essential tools for communities of practice (Wenger 2010). He differentiates boundary objects as ‘artefacts, discourses and processes’.

The first civic pedagogy, situated in Mumbai, India, was developed with NGO Muktangan School and the Mariamma Nagar neighbourhood. Lovegrove School, one of 7 Muktangan schools in the area, caters for low-income local communities and is housed in a municipal five-storey Government School building. Living and working in Mumbai from 2011 to 2017, I was embedded in the city as a designer and a researcher and architect-facilitator. 40 workshops to explore, assess and design for the local neighbourhood were held (in Hindi and English) across 5 years with the same class of schoolchildren and school staff.

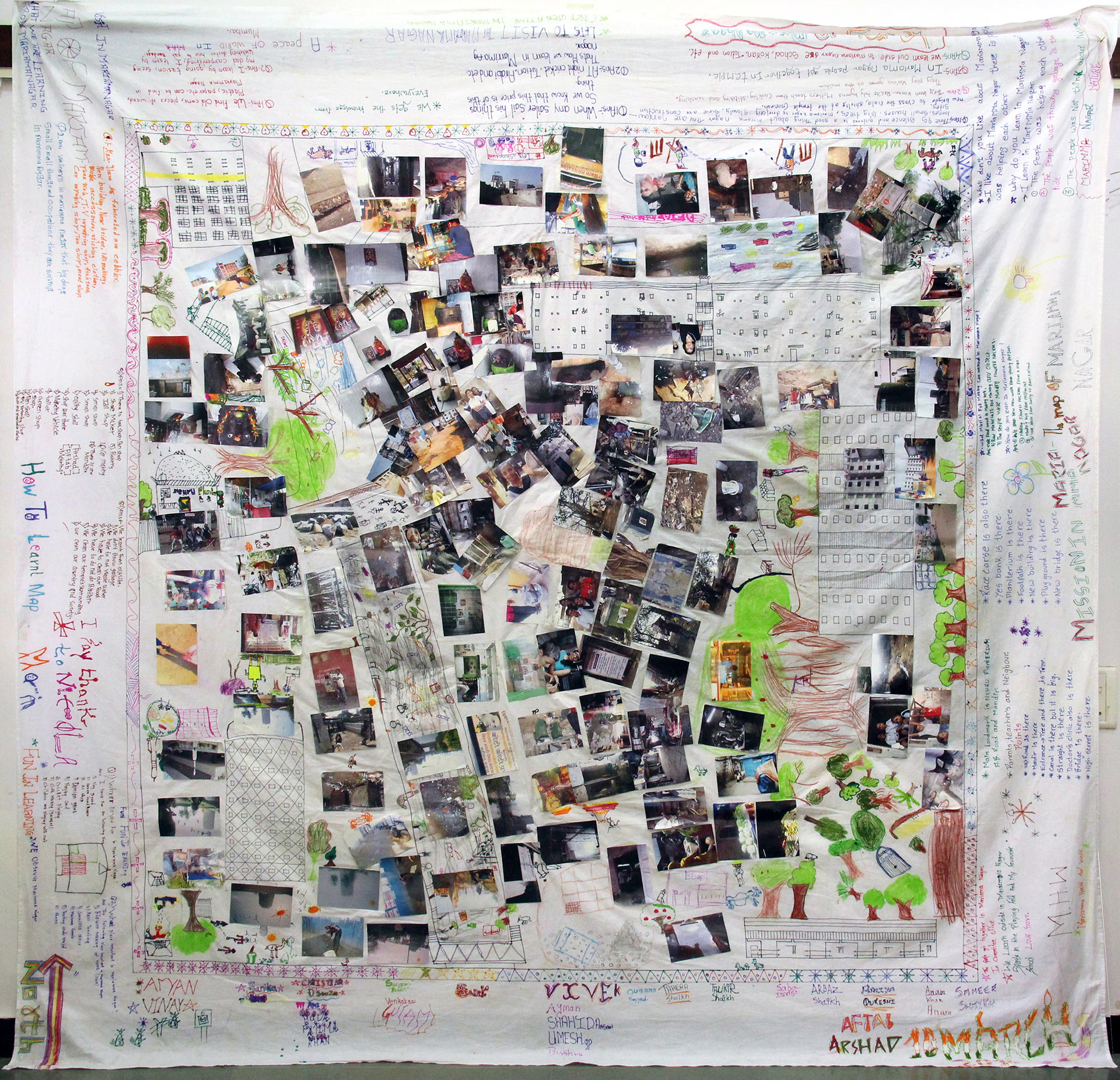

One of the workshops involved students observing, thinking critically about, and documenting learning in their neighbourhood. This was followed by reflection back in the classroom. A template for a map had been pre-prepared by the facilitator, with hand-drawn landmarks so that the students could orient themselves on the ‘page’, a large white cotton bedsheet. This base would support the creation of a map, fabricated together as a group, with students invited to position printed photographs and add drawings and notes. It was designed in such a way as to facilitate the students’ capacity to creatively document their fieldwork. The cotton map template was designed to be a boundary object between the students, architect-facilitators and the neighbourhood.

Muktangan Love Grove School students’ map of learning in the Mariamma Nagar neighbourhood, Mumbai, 2014. Photo: Nicola Antaki

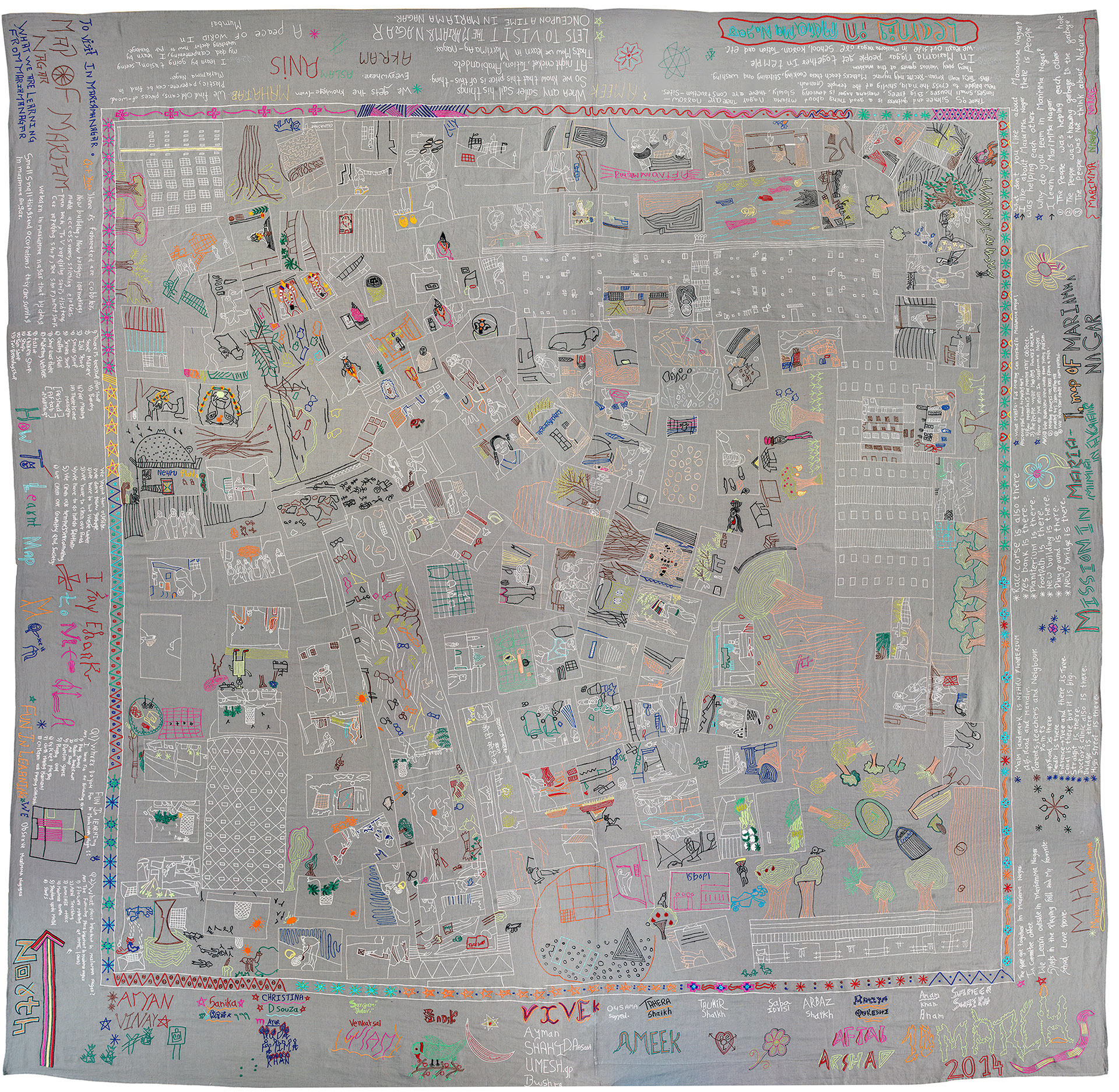

Its next interaction was with the craft community of practice in the neighbourhood, when it was translated into an embroidered tapestry. The tapestry was commissioned as a conversation piece for the project that could withstand time, travel and storage, reflecting the importance of cloth and embroidery in the local site and Indian culture (Antaki 2019). As a boundary object it inhabits and speaks to several communities of practice with different meanings and interpretations: the school (students and teachers) as a creative neighbourhood project, the residents (families and neighbours) as a map, and the craftsperson as a produced artefact showcasing their work. The tapestry also represents the new community of practice developed through the project, evolving through a series of actions and re-interpretations.

Embroidered tapestry made by craftsperson Mohammed Sheikh in the Mariamma Nagar neighbourhood as an interpretation of the Muktangan Love Grove School student’s map of learning, Mumbai, 2014. Photo: Nicola Antaki

The second civic pedagogy project, to co-design an EcoLab (ecological laboratory) in school premises with school pupils, is situated at the La Courtille middle school in Saint Denis, a suburb to the north of Paris. The EcoLab project, initiated by Atelier d’Architecture Autogerée (AAA) with support from the local council and the department, is part of a European research project CoNECT, of which AAA and the Chaire EFF&T research centre at the ENSAPLV – La Villette architecture school in Paris, constitute the French team. The EcoLab will be a part of the R-Urban network of community resilient spaces in Europe (Petcou and Petrescu 2015).

Saint Denis is a predominantly working-class city with a high proportion of young people. The EcoLab will be a space for learning outdoors at school but also aims to be open to the public and organisations out of school hours, fostering a new network for collaboration between existing and new partners in the local area, to learn and encourage ecological practices.

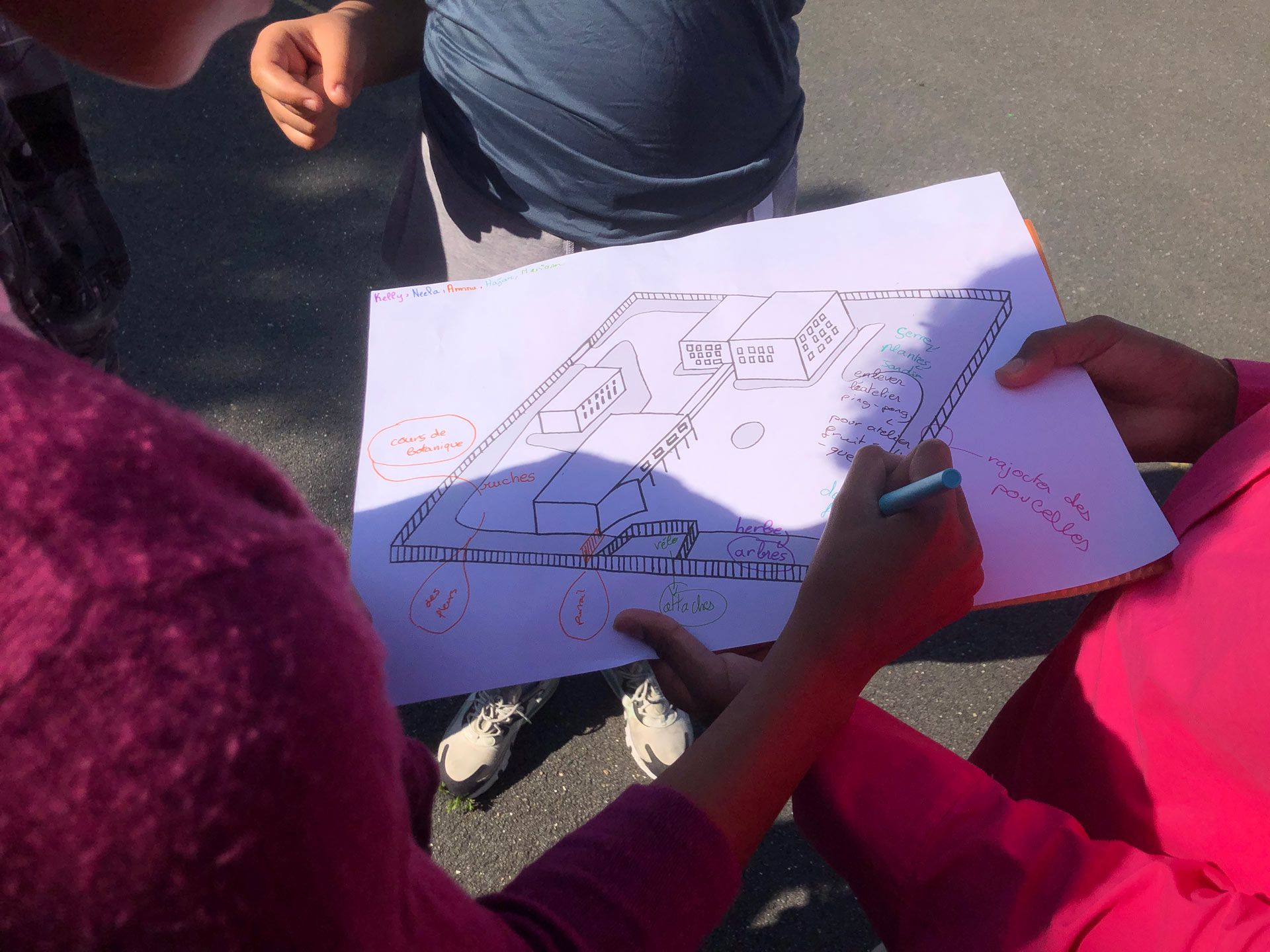

At the time of writing there had been 7 workshops with students: Some mapping ecological opportunities in the neighbourhood, expanding on walkabout methods in Mumbai – others developing designs for the EcoLab itself. For these workshops, co-design tools in the form of structured drawing templates were developed, so that each student could design an EcoLab individually, drawing on a base developed by the architect-facilitators. Further workshops enabled the co-design of an itinerant EcoLab exhibition, again using such tools, for boundary commoning between teachers, architect-facilitators, and students.

La Courtille middle school student sustainability representatives during an EcoLab design walkabout in the school grounds, Paris 2023. Photo: Nicola Antaki

The most long-standing boundary object is the garden itself, the soil. To begin interaction with the site, a workshop with students was led by landscape designer Fabien David (FADA) to investigate the ground and start to co-create the garden by identifying soil types, appropriate plant species, and planting seeds. The soil is the artefact; the material and gardening tools are used to engage with it. The soil is approached and understood in different ways by each community of practice – as a learning tool and site of discovery by the students, as a teaching tool and site of research by the landscape-facilitator, as property and risk by governing bodies, and as an object for sharing and commoning by the architect-researchers.

Year 7 students during an EcoLab soil workshop at La Courtille School led by landscape designer Fabien David, Paris 2023. Photo: Elsa Goujon

As the project progresses, the soil and garden will continue to evolve, formalising and organising into an ordered space, used by different groups for various activities; boundary objects will adapt to the community of practice that emerges through the EcoLab. However, as Star warns there is a risk of standardisation of boundary objects in time, that may exclude groups. It is important to allow boundary objects to act towards ‘interpretive flexibility.’ (Star 2010)

In civic pedagogies, boundary objects are essential tools for learning and knowledge sharing. They can be designed artefacts and tools for and of collective action; and existing materials and sites that are engaged with by diverse communities of practice, in ‘an arrangement that allow(s) different groups to work together without consensus.’ In the case of the collective design practice in Mumbai, a designed artefact – a tapestry – was worked on and understood by three different communities of practice. As an exhibition piece, it enables wider engagement, travelling to different countries, and being shown in varying contexts (schools, galleries, universities, museums); but also, the built environment of neighbourhood Mariamma Nagar, that became the site for student civic design interventions. In the case of EcoLab, France, a natural material, the soil and landscape, a site for co-making a space and a garden is able to provide for an alliance between students, teachers, designers, researchers, governing bodies and in the future, local organisations and inhabitants.

These boundary objects are necessary for facilitating research, encouraging alternative alliances and creating new communities of practice. They are necessary to enable multiscalar interactions and engagements with processes, at individual scales and larger group scales, allowing for independent production while also allowing for a movement towards mutual understanding.

References

Antaki, Nicola. 2021. “A Learning Architecture: Developing a Collective Design Pedagogy in Mumbai with Muktangan School Children and the Mariamma Nagar Community.” Research for All 5 (1): 101–117. https://doi.org/10.14324/RFA.05.1.09.

Antaki, Nicola, A. Belfield, and T. Moore. 2024. “Radical Urban Classrooms: Civic Pedagogies and Spaces of Learning on the Margins of Institutions.” Antipode 56 (5): 1509–1534. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.13039.

Freire, Paulo. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Seabury Press.

Giroux, Henry A. 2010. “Rethinking Education as the Practice of Freedom: Paulo Freire and the Promise of Critical Pedagogy.” Policy Futures in Education 8 (6): 715–721.

Gruenewald, David A. 2003. “The Best of Both Worlds: A Critical Pedagogy of Place.” Educational Researcher 32 (4): 3–12.

hooks, bell. 1994. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge.

Petcou, Constantin, and Doina Petrescu. 2015. “R-URBAN or How to Co-Produce a Resilient City.” Ephemera 15 (1): 249–262.

Star, Susan Leigh. 2010. “This Is Not a Boundary Object: Reflections on the Origin of a Concept.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 35 (5): 601–617.

Star, Susan Leigh, and James R. Griesemer. 1989. “Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39.” Social Studies of Science 19 (3): 387–420.

Tan, Pelin. 2021. “Alternative Alliances.” Urgent Pedagogies. https://urgentpedagogies.iaspis.se/alternative-alliances/. (Accessed January 28, 2025).

Wenger, Etienne. 1999. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, Etienne. 2010. “Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems: The Career of a Concept.” In Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice, edited by Chris Blackmore, 179–198. Springer.

The Sharing Practices Workshop

Pia Palo, Marco Adelfio, Emilio Brandao

Exploring local vocabularies and practices of circularity and sharing, snapshots of workshop steps. Photo: Pia Palo and Emilio Brandao

Sustainability, circularity, sharing… So what?

The workshop method outlined in this paper is part of ongoing research work in Hammarkullen, Gothenburg – a neighbourhood built in the 1960s as part of the Swedish Million Homes Programme (Hall & Vidén, 2005). This work maps the historical evolution of local community resources and actors through interviews with individuals involved in circularity and sharing practices emphasising their social and everyday dimensions (Hobson, 2020). Experiences from this work have raised questions regarding what it means to talk about concepts such as sustainability, sharing, and circularity without a locally established (and collectively shared) vocabulary around them.

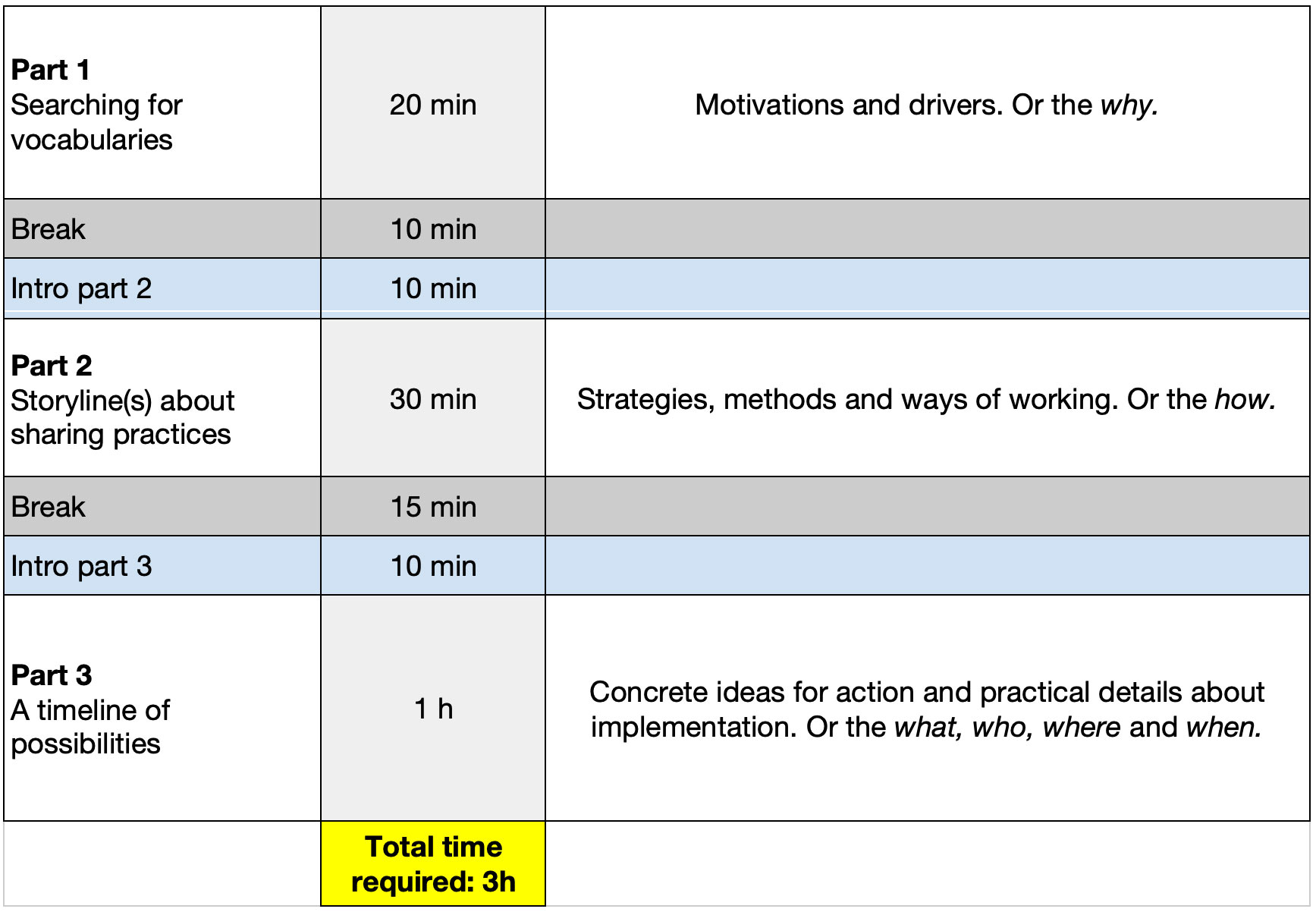

The workshop method of this paper aims, therefore, first to understand the local vocabulary in Hammarkullen, connected to practices of sharing and circularity. Then, with that as background, it collectively investigates potential futures for the sustainability of those practices in that specific context. The workshop looks at both formal and informal, top-down and bottom-up dichotomies that emerge from the contextualisation of the circularity issue. The procedure of the workshop experiments with the co-analysis of interview material, video documentation and the dynamic use of the workshop spaces. Participants included Hammarkullen residents, representatives from community groups and local initiatives, some of whom had previously participated in interviews in the project. Said interviews also included teaching staff and students from universities, representatives from municipal government and publicly owned entities at both the city level and from those present in Hammarkullen, such as the local housing company. Since the workshop in part builds on material from the interviews (as will be shown in the following sections), this constellation of participants is important to note. It intentionally shifted, and the workshop was a moment for people from Hammarkullen, part of and/or embedded in local practices, to, in a space without institutional actors present, explore the meaning of sustainability, circularity and sharing in their local context. This text is about the workshop method itself and does not delve into the findings resulting from its application.

Societal engagement in the design of co-creation processes (Bujodosó 2019) has a long-standing tradition (Blundell, Petrescu & Till 2005) and participatory workshop as a method (Chambers 2002; Martin & Hanington 2012) has taken a multiplicity of forms and is widely used in the disciplines related to the built environment. Still, beyond the formalistic processes of participation, which are not exempted from criticism (Miessen 2010), it is crucial to collaboratively create “actionable knowledge” (Kelly & Cordeiro 2020, p.1) relevant for the local community and context where it is developed (Greenwood 2007). This kind of knowledge (directly applicable in action) is especially relevant when discussing future scenarios of community development. Here, speculative thinking becomes a tool for investigating a challenge or need for change, building on the tradition of future workshops from the 1980s (Jungk & Muller 1987). They moved from the critical discussion of a topic to then co-create a vision and evaluate its possible practical implementations. This type of forward-looking engagement is linked to the notion of radical futurisms (Demos 2023), when future visions incorporate a dimension of societal justice. Methodologically, design futures encompass a variety of methods, and the documentation of design futures workshops includes a range of diverse media. This also contributes to the creation of “mediated experiences” as output (Kelliher & Bryne 2015, 3).

A collective search for a shared vocabulary, image from the first part of the workshop. Photo: Pia Palo and Emilio Brandao

The first part of the workshop centred around the meaning of circularity and sharing for the participants, individually and collectively, to lay a foundation for the coming tasks and discussions. Behind this aim were reflections from interviews conducted before the workshop, reflections about the abstract nature of these terms and a gap in the discourse around what they might mean on a hyper-local neighbourhood scale. The questions guiding the session were: Is circularity and sharing important in Hammarkullen? If so, why? And what are the words that you use to describe them?

As a pre-task before the workshop, the participants were asked to send in a handful of photos that represented practices of circularity and sharing. Combining these photos became the starting point of the task. During the session, the participants worked in two steps and were asked to:

- Choose photos from the shared library that they thought symbolised the concepts of circularity and sharing. They were prompted to consider the relationship between these concepts and their neighbourhood.

- Place the photos on a large piece of paper in the middle of the table where they were all seated and add a short description and/or keywords that capture why they had chosen the photos.

The participants shared thoughts informally as they worked, got sidetracked when they discovered common interests, returned, and added notes to photos that others had brought. The resulting collage could be understood as a local vocabulary in the making.

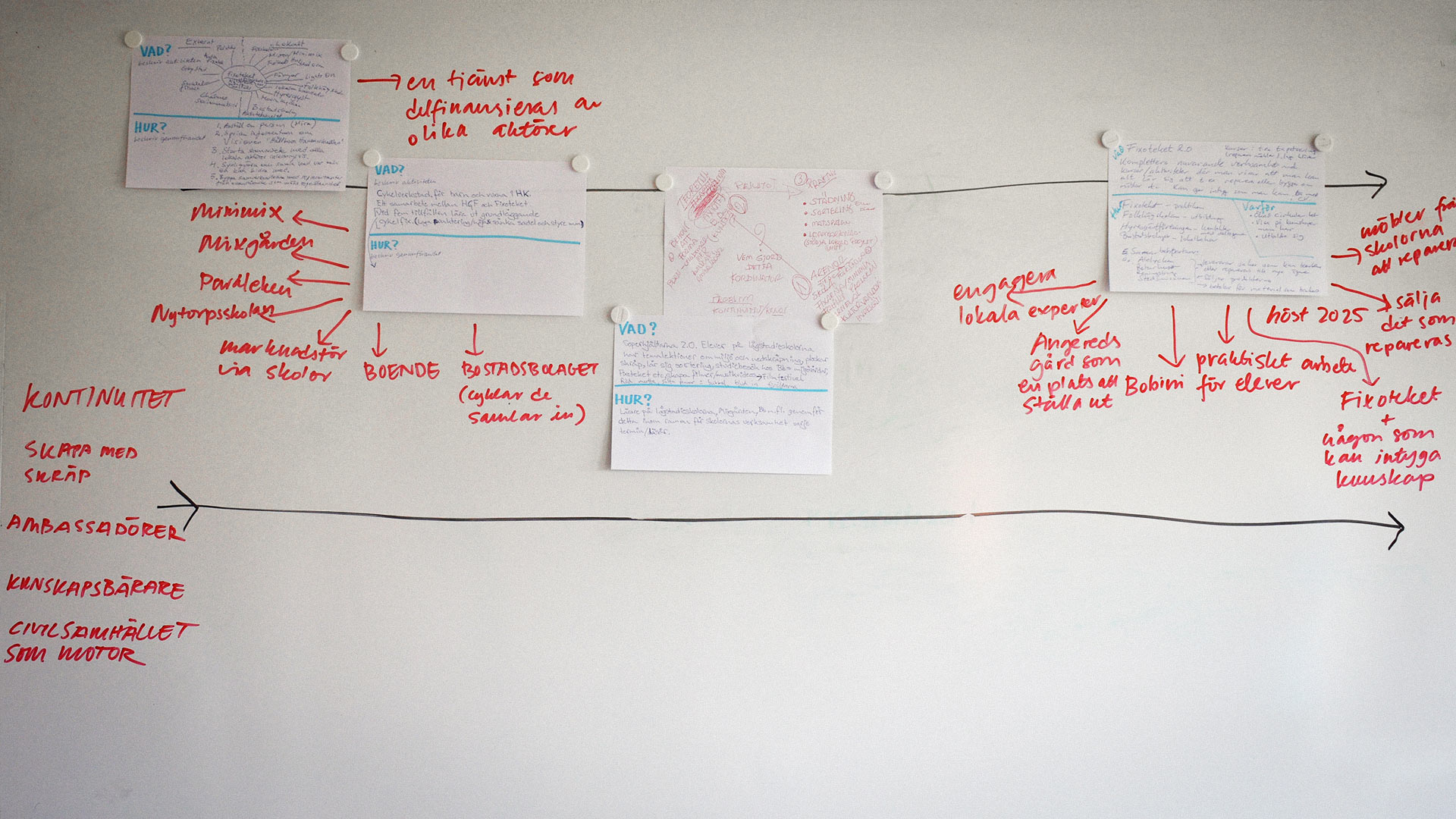

Building storylines of local practices, image from the second part of the workshop. Photo: Pia Palo and Emilio Brandao

In the second part of the workshop, quotes extracted from interviews previously conducted in the research project were used as working material. The selected quotes all said something about the understandings and potentials of how activities and ideas in Hammarkullen are planned and made possible. The quotes also left some gaps and open endings to be a bit suggestive, to spark thoughts about new connections between and continuations of existing local practices.

Space organisation played an important role in setting up the session. A long table, with the quotes laid out on top, was set up opposite a wall where a long paper was pinned. Moving back and forth between the table and the wall, introducing small moments for shifting attention, the participants were asked to:

- Pick up quotes from the table that interest you. Pick several, think about how they connect and relate to each other.

- Place the quotes on the long paper on the wall. Draw the connections and create a “storyline” consisting of multiple quotes. You can build onto other people’s storylines, merge, branch, or start new strands of quotes.

- Add your own thoughts and associations to the storylines, fill in the gaps, ask questions, highlight keywords.

The participants worked individually but built on the storylines of others, merging and branching ideas. Working in a “what if…?” speculative manner, they filled in gaps, adding to the insights from the interviews.

Proposing and discussing ideas for future actions. Photo: Pia Palo and Emilio Brandao

While the first and second parts of the workshop worked on a more abstract plane, with ways of naming and thinking about the approach to practices of circularity and sharing, the third part focused on reaching concrete ideas about potential action. The aim was to bring the thoughts and ideas from the previous step into relation with existing actors and resources in Hammarkullen and develop a series of activities that could be implemented in the near future. The questions guiding the session were “And then what? What do we do, and where do we go together as a neighbourhood?”

The participants were divided into pairs, each tasked with developing one to three ideas for activities. They were prompted to think in terms of collaborations, about interests that might overlap, resources that could be shared and other things that would enable the activity to become reality. Each pair presented their ideas to the group, which responded with further input. The group then discussed the ideas in relation to one another, identifying a sequence of actions—what would happen first, logical next steps, and so on. This process generated a timeline of future possibilities, including concrete suggestions for spaces, resources, participants, and responsibilities.

In response to the perceived lack of local anchoring of concepts such as sustainability, circularity, and sharing, the workshop explored spatial configurations, video documentation, and the integration of empirical material as means of fostering co-produced and co-analysed knowledge. The spatial setups aimed to articulate different aspects of knowledge co-production—from the shared table where a collective vocabulary was built in step one, to the movements across the room and moments of pause and reflection in step two, and the structured evaluation and visualisation of future actions in step three. Video documentation, particularly time-lapse, helped capture key moments, showing how ideas evolved and intertwined across the three steps. The introduction of previously collected empirical material (interview quotes and visuals) grounded the process in existing knowledge, both that of participants and researchers, while simultaneously leaving sufficient open ends for creating new lines of thinking.

While the workshop succeeded in creating a transformative space for co-production, some challenges remain. For instance, although the distinct spatial setups clearly marked each step, they also introduced a degree of discontinuity, making it harder to convey the process as a cohesive whole. Furthermore, how to carry forward the proposed actions from step three—and how to effectively share these insights with local decision-makers—requires further development.

In closing, the strength of this method lies in its potential to root abstract concepts in local vocabularies and lived practices, building onto existing networks and local knowledge rather than trying to prescribe preexisting solutions and systems. Moving from the more general, defining the shared vocabulary, to outlining local practices, and finally coming up with concrete suggestions for actions made for projective and rich conversations. Having these kinds of exploratory and experience-based discussions around concepts such as sustainability, circularity, and sharing are crucial, especially since dominant approaches often prioritise technological efficiency and green market growth while overlooking the social dimensions of circularity, thereby risking the failure of transitioning away from linear economies (Ziegler et al., 2023).

Refining the method—its spatial design, documentation tools, and workshop materials—is a next step in nurturing locally anchored, resilient actions toward collective transformation.

References

Blundell Jones, Peter, Doina Petrescu, and Jeremy Till, eds. 2005. Architecture and Participation. London and New York: Spon Press, Taylor and Francis Group.

Bujdosó, Attila, Martijn de Waal, and Jaakko Blomberg, eds. 2019. Social Design Cook-Book: Recipes for Social Cooperation. Budapest: Attila Bujdosó.

Chambers, Robert. 2002. Participatory Workshops: A Sourcebook of 21 Sets of Ideas and Activities. London; Sterling, VA: Earthscan Publications.

Demos, T. J. 2023. Radical Futurism. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Greenwood, Davydd. 2007. “Pragmatic Action Research.” International Journal of Action Research 3: 131-131.

Hall, Thomas, and Sonja Vidén. 2005. “The Million Homes Programme: A Review of the Great Swedish Planning Project.” Planning Perspectives 20 (3): 301–28.

Hobson, Kersty. 2020. “‘Small Stories of Closing Loops’: Social Circularity and the Everyday Circular Economy.” Climatic Change 163: 99–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02480-z.

Jungk, Robert, and Norbert Müllert. 1987. Future Workshops: How to Create Desirable Futures. London: Institute for Social Inventions.

Kelliher, Aisling, and Daragh Byrne. 2015. “Design Futures in Action: Documenting Experiential Futures for Participatory Audiences.” Futures.

Kelly, Leanne M., and Maya Cordeiro. 2020. “Three Principles of Pragmatism for Research on Organizational Processes.” Methodological Innovations 13 (2): 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059799120937242.

Martin, Bella, and Bruce Hanington. 2012. Universal Methods of Design: 100 Ways to Research Complex Problems, Develop Innovative Ideas, and Design Effective Solutions. Beverly, MA: Rockport Publishers.

Miessen, Markus. 2010. The Nightmare of Participation. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Ziegler, Rafael, Thomas Bauwens, Michael J. Roy, Simon Teasdale, Ambre Fourrier, and Emmanuel Raufflet. 2023. ‘Embedding Circularity: Theorizing the Social Economy, Its Potential, and Its Challenges’. Ecological Economics 214 (December):107970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2023.107970.

Community-engaged Design-build Pedagogy of and for the Commons: Reflections on the “Cocreation Studio” Activities in Suburban Nicosia

Effrosyni Roussou

Construction work at Latsia Highscool. Students building the pavilion. Photo: Effrosyni Roussou

Any form of architectural pedagogy without contextual considerations often results in an uncritical reproduction of hegemonic (western, colonial, capitalist) discourses (Olweny 2022; Salama 2019). Amidst a renewed interest in the decolonisation of curricula across the globe, “canonical”, i.e. hegemonic architectural pedagogies have come under criticism due to their decontextualisation and isolation from real-world contingencies (Till 2009; Parnell 2003). In this text, canonical architectural pedagogies are understood as pedagogies centred on a western-developed, classroom-based design studio. Its focus lies predominantly on developing students’ design rather than soft skills (e.g. communication, empathy, etc), often overlooking the need to critically examine the role architects play in shaping local contexts. This results in the reproduction of a depoliticised involvement in spatial production (Doucet 2017; Lorne 2017). Such an involvement fails to challenge the ongoing fast-track financialisation -or enclosing– of spheres of human activity and (spatial) resources that were previously governed by types of value other than economic (Brown 2015; De Angelis 2015).

Seeking architectural pedagogies beyond the hegemonic canon becomes, therefore, a process of reclaiming value. Live pedagogies, in the form of participatory and design-build projects, much like commoning processes, have proven to be crucial tools in decentring dominant narratives, renegotiating the types of knowledge(s), relations and processes that are valuable beyond the false universality of the western model, and recontextualising the learning process (Abrahams et al. 2021; Awan, Schneider, and Till 2011; Harriss and Widder 2014; Petrescu and Trogal 2017). Commoning in this context is understood as the collective practices of (re)production, care and stewardship of a shared resource (e.g. space, knowledge) (Bollier 2021; Stavrides 2016).

In pre-colonial Cyprus, commoning as an everyday way of managing shared resources was a “common” practice (Dietzel 2016). It has, however, been eroded due to the persistent, overlapping crises that have been affecting the area, which are arguably direct by-products of its colonisation and the epistemological assertion of modernity and capitalism (Mignolo 2011). By focusing on Cyprus, this research aims to explore architectural pedagogies beyond the hegemonic canon. Reconnecting to the collective practices of (re)claiming value and creating belonging, both in what we do (“for the commons”) and how we do it (“of the commons”) becomes a matter of urgency towards spatial and social justice.

The two main questions that this research attempts to address are: (1) how can we reconceptualise architectural pedagogy as pedagogy of and for the commons, through a community-engaged and design-build framework, and subsequently, (2) how does such a pedagogy influence students’ perception regarding their own role and capacity to safeguard a just spatial production? These questions are explored through community-engaged, design-build activities taking place in the suburbs of Nicosia, Cyprus, under the umbrella entity of the “cocreation studio” initiated by the University of Cyprus (Instagram: @cocreationstudio.ucy).

The transition of Cyprus, and by extension Nicosia, from a British colony to the ethnically divided postcolonial terrain that it is today, came with rapid shifts in governance and land management, in an effort to speed-up the process of modernisation. Participation in planning was thought of as inefficient “in developing countries”, (Ioannou 2016, 81) which nurtured a disconnection between (public) land and people, while the absence of planning legislations contributed to the uncontrolled urban sprawl and dysfunctional urban spaces (Ioannou 2016). It is in this context that the “cocreation studio” attempts to create impact in the way architecture students and local communities relate to and care for urban space, through community-engaged design-build activities.

The structure of the cocreation studio activities draws from the live studio methodology, and specifically from examples such as Dare to Build, and Design and Planning for Social Inclusion at Chalmers University of Technology, Live Projects at Sheffield School of Architecture, and Rural Studio at Auburn University. The collaborative design activities occur as a number of meetings and workshops with the participating stakeholders during the spring semester. These activities are part of the compulsory year 2 design studio, and are followed by an elective course, available to year 2, year 3, and year 4 students, during which the construction phase takes place. The structure of the activities is designed as an iterative process consisting of four stages:

- Tune in: Students explore new concepts and familiarise themselves with the context of operations and the stakeholders. They jointly explore the particularities of the context, as well as the need of the future users (co-analysis).

- Experiment: Loops of joint design experimentations and feedback (co-design). Through an open voting process, all those involved (co-)select one or more projects, which will proceed to the building phase.

- Perform: The selected project(s) is constructed on 1:1 scale and delivered to its future users (co-implement, co-build).

- Evaluate: Collective evaluation of the process and the constructed outcome (co-evaluate, reflect)

During the studio activities, role-shifting becomes a key tool in reconfiguring both how students learn, and how they relate to other agents in urban space. Students are not only encouraged to “learn by doing”, but also to “learn by becoming”. In both the collaborative design and build phase, students may assume different roles and approach each task from different angles and diverse standpoints. They perform as mediators, community liaisons, project managers, graphic designers, and construction workers among others, which allows them to get a glimpse of what each of these fields of knowledge entails. This encourages them to cultivate empathy and care, acknowledging and learning from each individual contribution towards the collective goal. This aids not only in emphasising the fluidity of architecture as a socio-spatial practice, rather than a clear-cut discipline, but also in reshaping the learning process as a commoning process, i.e. a process of collective care and production of knowledge and its spatial implications/applications.

On an epistemological plane, framing the learning process within a live pedagogical module as commoning, contributes to challenging what constitutes the standard conceptions of the tools and knowledge(s) within architecture. It pushes towards perpetual exploration, both of the aforementioned tools and knowledge(s), and subsequently, of oneself as “knowing subject”. In other words, “getting in someone else’s shoes” can be a way of caring, of critically reflecting on the kinds of knowledge we engage in and generate. It can be a way to rethink our positionality as subjects who put this knowledge into use (Mignolo 2011), as well as on our responsibility and its trajectory, as socio-spatial practitioners.

As stated in the beginning of this text, the pedagogical method briefly presented above emerges from the necessity to “recontextualise” architectural education and renegotiate its hegemonic influences and implications. Recontextualising is imperative in repairing and reconfiguring the way we, as citizens and/or spatial practitioners relate to and care for the spaces we inhabit: their symbolic meaning, their history, as well as their present and future. This is all the more urgent in contexts of overlapping crises.

It is also imperative in rethinking the way we perceive our own positionality and subsequently the way we relate to others. This is where “role-shifting” may potentially contribute; both in challenging disciplinary boundaries, in terms of what skills and knowledge(s) are considered relevant or useful for a future architect, but also in creating bonds of care through tangible experience. Arguably, “putting oneself in someone else’s shoes” even in a simulated manner, as it is through a pedagogical activity, could aid in reconsidering our perceptions/preconceptions of others. For example, after the completion of one of the cocreation studio projects, several students mentioned that having the opportunity to engage in hands-on work, on a “real” construction site, enabled them to better understand what the job of a construction worker entails. This, according to them, renders them more aware of the potential implications of their design choices on those who will be called to bring a project to life.

Finally, and in regards to reconceptualising an architectural education of and for the commons, recontextualisation is key; “what we do” and “how we do it” does not happen in a vacuum, therefore the tools, methods and overall ways used towards that goal, need to (co)respond to the current contextual conditions, histories and peoples. There are, however, two main lingering questions: The first one relates to whether, and, if yes, how can commoning as a way of practicing direct, non-hierarchical and often spontaneous stewardship over a commons, such as knowledge and urban space, be institutionalized within an architectural education which at its core remains a product of modernity, without losing its radical potential. The second one, equally, if not more important, revolves around the potential of such a commons-oriented pedagogical methodology to address the tangible hegemonic legacies still dominating contexts of crises; in Cyprus, for example, could such a pedagogy contribute towards fostering intercommunal relations across the divide?

The material is based on the author’s doctoral research, conducted under the auspices of RE-DWELL MSCA-ITN (H2020 956082).

More information can be found at the project website https://www.re-dwell.eu/

References

Abrahams, Clint, Hermie Delport, Rudolf Perold, Anna Marijke Weber, and James Benedict Brown. 2021. ‘Being-in-Context through Live Projects in Architectural Education: Including Situated Knowledge in Community Engagement Projects’. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning 9 (SI): 99–125. https://doi.org/10.14426/cristal.v9iSI.337.

Awan, Nishat, Tatjana Schneider, and Jeremy Till. 2011. Spatial Agency: Other Ways Of Doing Architecture. Routledge.

Bollier, David. 2021. The Commoner’s Catalog for Changemaking. Schumacher Center.

Brown, Wendy. 2015. ‘Undoing Democracy – Neoliberalsm’s Remaking of State and Subject’. In Undoing the Demos, Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution, 17–45. Zone Books.

De Angelis, Massimo. 2015. The Beginning of History: Value Struggles and Global Capital. Pluto Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt18mvp2n.

Dietzel, Irene. 2016. ‘Sharing Traditions of Land Use and Ownership: Considering the “Ground” for Coexistence and Conflict in Pre-Modern Cyprus’. In Post-Ottoman Coexistence, edited by Rebecca Bryant, 41–58. Berghahn Books.

Doucet, Isabelle. 2017. ‘Learning in the “Real” World: Encounters with Radical Architectures (1960s–1970s)’. Journal of Educational Administration and History 49 (1): 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2017.1252735.

Harriss, Harriet, and Lynnette Widder, eds. 2014. Architecture Live Projects Pedagogy into Practice. Routledge.

Ioannou, Byron. 2016. ‘Post-Colonial Urban Development and Planning in Cyprus: Shifting Visions and Realities of Early Suburbia’. Urban Planning 1 (4): 79–88. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v1i4.768.

Lorne, Colin. 2017. ‘Spatial Agency and Practising Architecture beyond Buildings’. Social and Cultural Geography 18 (2): 268–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2016.1174282.

Mignolo, Walter D. 2011. The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Latin America Otherwise. Duke University Press.

Olweny, Mark. 2022. ‘Questioning Conventions of Western Architectural Pedagogy in East Africa’. In The Routledge Companion to Architectural Pedagogies of the Global South, edited by Ashraf M. Salama, Harriet Harriss, and Ane Gonzalez Lara, 1st ed. Routledge.

Parnell, Rosie. 2003. ‘Knowledge Skills and Arrogance: Educating for Collaborative Practice’. In Writings in Architectural Education: EAAE Transaction on Architectural Education, edited by Ebbe Harder, 58–71. EAAE.

Petrescu, Doina, and Kim Trogal. 2017. The Social (Re)Production of Architecture: Politics, Values and Actions in Contemporary Practice. Routledge.

Salama, Ashraf M. 2019. ‘Reflections on Architectural Education of the Muslim World within a Global World’. International Journal of Islamic Architecture 8 (1): 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1386/ijia.8.1.33_1.

Stavrides, Stavros. 2016. Common Space: The City as Commons. Zed Books.

Till, Jeremy. 2009. Architecture Depends. MIT Press.

Unlearning to Build Better: Transformative Pedagogies for Holistic and Sustainable Renovation Practices

Eeva-Maarja Laur

This article provides an ethnographic account of the researcher’s engagement with the Culture and Environmental Collective since 2015. This community-led initiative adopts an experimental approach to sustainability, focusing on renovating a former factory building. The study seeks to explore pedagogical practices that can facilitate the development of holistic, sustainable building renovation approaches. The article begins by introducing the case study and analysing narratives about the environmental experiences of collective members through the concept of Genius Loci (Norberg-Schulz 1980). It then delves into the collective’s hands-on building workshop approach, providing an in-depth examination of its methods and outcomes. Finally, the article concludes with a discussion of a pedagogical framework for material strategies in relation to sustainable building renovation and self-building.

The Culture and Environmental Collective, based in Denmark, operates within a 10,000 m² former Knabstrup ceramic and brick factory. Established in 2008, the collective is driven by the voluntary efforts of both local and international participants who are joined by the drive to develop knowledge, skills, and practices related to culture and environmental sustainability. This “community of practice” (Lave and Wenger 1991) centres on addressing the global systemic issues of environmental degradation caused by unsustainable practices at both individual and collective levels. Through an international network, the collective promotes both global responsibility and local sensitivity (Wahl and Baxter 2008). Its self-build projects repurpose the 1622 industrial building for community use, integrating upcycled, reclaimed, or locally sourced materials within an experiential learning framework (Kolb 1984).

Over time, the collective has created a wide range of facilities, including accommodation, a shared dining space, areas for concerts and conferences, a co-working hub, a studio for movement culture, and workshops for developing craft skills. The initiative has gained recognition from local associations, municipalities, and philanthropic foundations for promoting local community development and innovative sustainable building practices that address the needs of current and future generations.

The Genius Loci of the former factory is a multi-dimensional phenomenon, blending physical and intangible aspects of the space. Norberg-Schulz’s (1980) interpretation of Genius Loci offers a lens for understanding how architecture relates to its region, environment, culture, and heritage. At this site, historical elements such as industrial iron window frames and exposed timber trusses coexist harmoniously with modern renovations, creating a dialogue between past and present.

The factory’s sensory experiences are rich and immersive, encompassing contrasts such as a cool draft in spring, frost on coffee cups, winter cold penetrating the bones, the daunting darkness versus amber-coloured light from the rocket stove, and cold, moist wooden floors and fresh clay plaster on walls. I argue, that these experiences align with Bennett’s (2020) concept of “vibrant matter”, which highlights the agency of non-human elements. The factory’s dynamic environment features ongoing renovations and guided tours to communicate its evolving use. Visitors frequently remark on the site’s enormous potential and experience a profound sense of awe (Walsh et al. 2020).

In essence, the factory’s Genius Loci embodies historical continuity, sensory richness, material agency, and diverse human and non-human interactions. It inspires creativity and demands sensitive navigation, fostering a space where past and present coexist in a vibrant dynamic. This immersive experience is not limited to human perception but extends to material agency and environmental interactivity, leading to a reconsideration of how we learn with, rather than just about, space. The following section explores how the workshop approach integrates these more-than-human elements into pedagogy.

The collective’s hands-on workshops emphasize the more-than-human perspective, engaging participants in direct interactions with materials, tools, and the built environment. This approach positions the factory itself as a co-actor in the learning process, extending Malaguzzi’s (2016) concept of the “third teacher” to constructed spaces.

The workshops integrate cognitive (head), affective (heart), and psychomotor (hands) domains (Sipos, Battisti, and Grimm 2008) to create a holistic learning experience. Through embodied and affective encounters, participants engage in transformative learning (Mezirow 1997), adapting mental models in response to their interactions with the environment and peers. This process highlights the co-evolution of human and non-human systems, challenging anthropocentric worldviews.

The emphasis on co-design with more-than-human actors and peer learning decentralises human agency, fostering collective wisdom that emerges through diverse human and more-than-human interactions. Aside from the individual’s perspective shift, the workshops have produced practical sustainability solutions such as design and renovation with ecological materials, an efficient heating system, and a local wastewater treatment system, underscoring the value of this collaborative approach to sustainability education.

Workshop participants engage in collaborative, material-driven renovation, where the agency of the historic factory’s brick and timber guides new, sustainable uses and learning experiences. Image courtesy of the author

Self-building is gaining traction across Europe, supported by local governments as a strategy to improve housing quality, sustainability, and affordability (Bossuyt 2021). In the UK, for example, the number of self-build homes increased by 50% between 2015 and 2020 (Ehwi, Maslova, and Burgess 2022). This trend reflects a broader European movement in engaging with self-building practices. Simultaneously, building renovation has become central to the European Commission’s efforts to reduce CO₂ emissions. The Renovation Wave initiative aims to double annual renovation rates by 2030, targeting 35 million building units (European Commission 2020).

Renovating buildings presents unique challenges, as it requires balancing architectural, social, and cultural values with energy efficiency and cost considerations. Most renovations are limited to mechanical installations and improved insulation, but holistic, sustainable practices are often overlooked (Herrera-Avellanosa et al. 2024). Expertise in building conservation and building physics, as well as an in-depth understanding of local cultural, environmental and socio-economic conditions, is essential to address the complex nature of sustainable building renovation.

To address these issues, future research should focus on developing a comprehensive pedagogical framework for sustainable building renovation. Such a framework would integrate ecological principles, cultural heritage conservation, and energy efficiency to create a context-sensitive methodology to identify case-specific renovation practices. By building on experiential, embodied, and more-than-human learning approaches, this research could explore how materials, spaces, and environmental dynamics could inform a holistic approach to building renovation. Additionally, designing collaborative learning models that emphasise peer interaction, community engagement, and expert mentorship would foster more effective and inclusive renovation projects. My findings from the process highlight the need for a radical rethinking of renovation pedagogy. Future research and practice should develop structured approaches for integrating such learning experiences that also need to become part of formal architectural education. Reorienting renovation practices toward holistic sustainability can foster a built environment that is both environmentally regenerative and socially inclusive.

References

Bennett, Jane. 2020. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press.

Bossuyt, Daniël M. 2021. ‘The Value of Self-Build: Understanding the Aspirations and Strategies of Owner-Builders in the Homeruskwartier, Almere’. Housing Studies 36 (5): 696–713.

Ehwi, Richmond, Sabina Maslova, and Gemma Burgess. 2022. ‘Self Build and Custom Housebuilding in the UK: An Evidence Review’. Cambridge Centre for Housing and Planning Research.

European Commission. 2020. ‘COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS A Renovation Wave for Europe – Greening Our Buildings, Creating Jobs, Improving Lives’. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:0638aa1d-0f02-11eb-bc07-01aa75ed71a1.0003.02/DOC_1&format=PDF.

Herrera-Avellanosa, Daniel, Jørgen Rose, Kirsten Engelund Thomsen, Franziska Haas, Gustaf Leijonhufvud, Tor Brostrom, and Alexandra Troi. 2024. ‘Evaluating the Implementation of Energy Retrofits in Historic Buildings: A Demonstration of the Energy Conservation Potential and Lessons Learned for Upscaling’. Heritage 7 (2): 997–1013.

Kolb, David A. 1984. ‘Experiential Learning: Experience Source Learning Development’. Englewood Cliffs.

Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning. Cambridge University Press.

Malaguzzi, Loris. 2016. Loris Malaguzzi and the Schools of Reggio Emilia. Edited by Paola Cagliari, Marina Castagnetti, Claudia Giudici, Carlina Rinaldi, Vea Vecchi, and Peter Moss. Contesting Early Childhood. London, England: Routledge.

Mezirow, Jack. 1997. ‘Transformative Learning: Theory to Practice’. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 1997 (74): 5–12.

Norberg-Schulz, Christian. 1980. Genius Loci. New York, NY: Rizzoli International Publications.

Sipos, Yona, Bryce Battisti, and Kurt Grimm. 2008. ‘Achieving Transformative Sustainability Learning: Engaging Head, Hands and Heart’. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 9 (1): 68–86.

Wahl, Daniel Christian, and Seaton Baxter. 2008. ‘The Designer’s Role in Facilitating Sustainable Solutions’. Design Issues 24 (2): 72–83.

Walsh, Zack, Jessica Böhme, Brooke D. Lavelle, and Christine Wamsler. 2020. ‘Transformative Education: Towards a Relational, Justice-Oriented Approach to Sustainability’. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 21 (7): 1587–1606.

Learning With and From a Slow Garden in Tynnered, Gothenburg

Sadia Sharmin

Environmental learning is a dynamic social process shaped by interactions among people and influenced by the broader socio-cultural and biophysical contexts they inhabit (Lave and Wenger 1991; Marsick and Watkins 2018; Rogoff 1994; Vygotsky 1978). While traditional models of learning often emphasise structured settings such as schools and classrooms, this focus can overlook the diverse informal contexts in which significant environmental understanding emerges through everyday experience. Nicole M. Ardoin and Joe E. Heimlich (2021) examine the concept of the “learningscape”, which reimagines learning as inseparable from the social and ecological systems that surround us (Oakes et al. 2015; Tidball and Krasny 2011). Central to this framework is the role of incidental experiences, particularly within “interstitial spaces”—the in-between moments and places where people engage in informal, often unintentional learning (Ardoin and Heimlich 2021). These spaces become vital sites for meaning-making, transforming previously fragmented experiences into cohesive, place-based insights.

However, non-formal and unintentional learning opportunities in everyday life remain underexplored in the environmental education literature (Marsick and Watkins 1990, 2001, 2018; Spear and Mocker 1984; NRC 2009; Watkins et al. 2018), as well as within spatial practice discourse. This study seeks to address that gap by examining one such interstitial setting—Safirträdgården—to explore its role in enabling meaningful engagement and experiential learning beyond formalised educational environments.

Located in Tynnered, a neighbourhood in Gothenburg shaped by Sweden’s Million Programme housing initiative of the 1960s and ’70s, Safirträdgården [Sapphire Garden] operates within a socio-spatial context marked by systemic inequality. For over a decade, Tynnered has been labelled a “vulnerable area” by the Swedish police, with its diverse community often framed by stigmatising narratives that attribute social issues such as crime and poverty to the residents themselves, rather than to structural root causes. These dominant portrayals perpetuate discrimination and exclusion, reinforcing a cycle of marginalisation and hindering authentic community-engaged development (Tahvilzadeh 2021).

In contrast, grassroots initiatives like Safirträdgården offer a counter-narrative—grounded in local agency, relational care, and situated knowledge. Initiated by a mother and son, the garden has become a meeting place where residents—particularly children and families—are invited to co-shape their environment through creative, hands-on practices.

I became acquainted with Safirträdgården through my master’s thesis at Chalmers (2024). My research project employed visual, ethnographic, and participatory methods. By tracing the tools, routines, and strategies used to sustain the garden, my study examined how Safirträdgården has evolved into a meaningful shared space through small acts of care that ripple outward to inspire broader community engagement. My research tells the story of the garden and highlights how such grassroots initiatives generate informal yet impactful environments for children, young people, and parents. Safirträdgården exemplifies the pedagogical potential of grassroots public spaces—functioning not only as places for community gathering but as vibrant environments where ecological understanding, creativity, and non-formal education intersect beyond institutional structures.

A neighbour reads to the children at Safirträdgården. Photo: Monika Tildevik

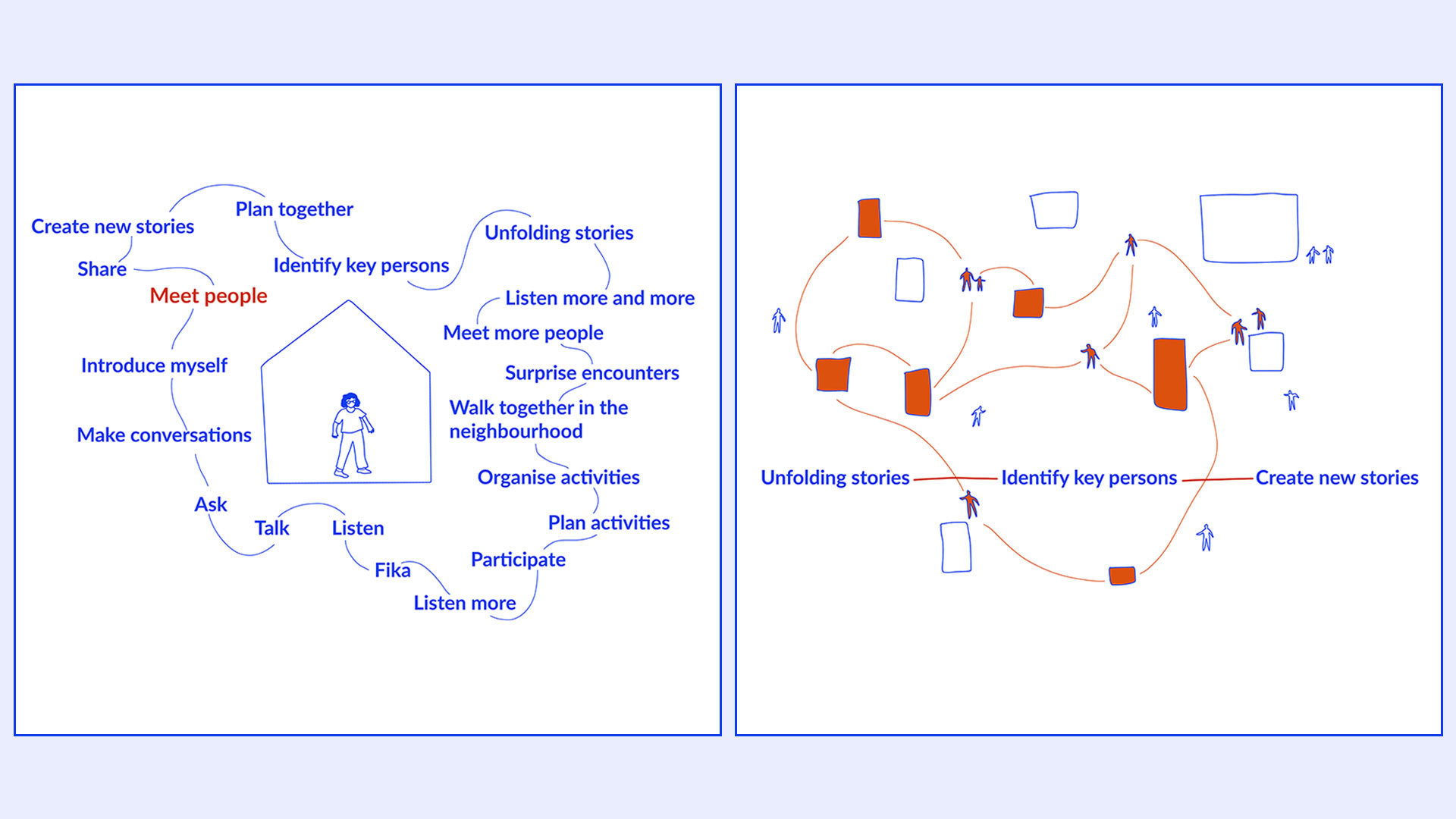

Inspired by Clifford Geertz’s concept of “deep hanging out” (1998), my research methodology emphasises Being Present—an immersive mode of engagement that goes beyond observation to respond to the community’s evolving dynamics. As part of the process, I became a proactive participant—initiating dialogue, hosting workshops, and collaborating with community members to co-create events—while fluidly adapting roles according to context and weaving together insights from diverse encounters.

Within the broader framework of my research on community-engaged placemaking and placekeeping, I took on an active role at Safirträdgården. As a researcher, I contributed to documenting the ongoing care and placekeeping practices, co-organised events for children, and facilitated brainstorming sessions about small-scale design interventions—both within the garden and in the surrounding neighbourhood. I also supported outreach by connecting with local youth and encouraging their involvement in hosting events for children. Additionally, I shared what we were learning from the garden by presenting at “community breakfast meetings” attended by representatives from housing organisations, schools, and local NGOs. This hands-on involvement not only deepened my understanding of the garden’s role but also allowed me to support the caring ways that brings people together.

My study also highlights the use of creative tools to analyse and reflect on collective knowledge. Through drawing, visual storytelling, and ethnographic narrative, the research communicates insights as forms of creative advocacy—inviting broader conversations and resonating with audiences beyond the immediate community.

BEING PRESENT — A continuous process of interconnected actions. Visualisation: Sadia Sharmin

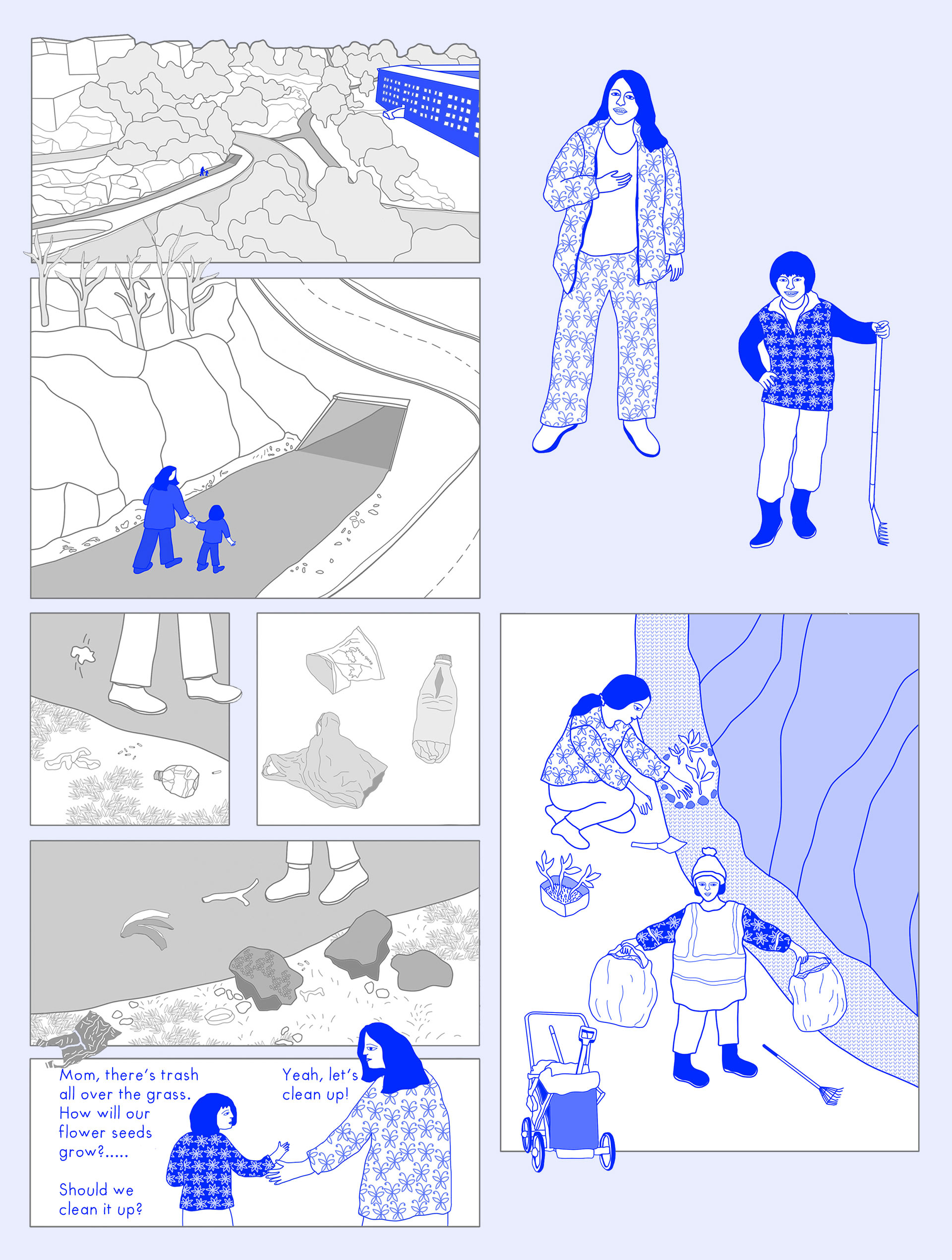

Safirträdgården emerged from a simple desire to create a safer, more welcoming environment on Briljantgatan in Tynnered—an area previously perceived as unsafe. In early 2020, Monika and her then five-year-old son, Tristan, took the initiative to clean up their neglected street. They began by collecting litter and scattering flower seeds, sparking a chain reaction of community involvement that gradually led to the creation of a communal meeting place.

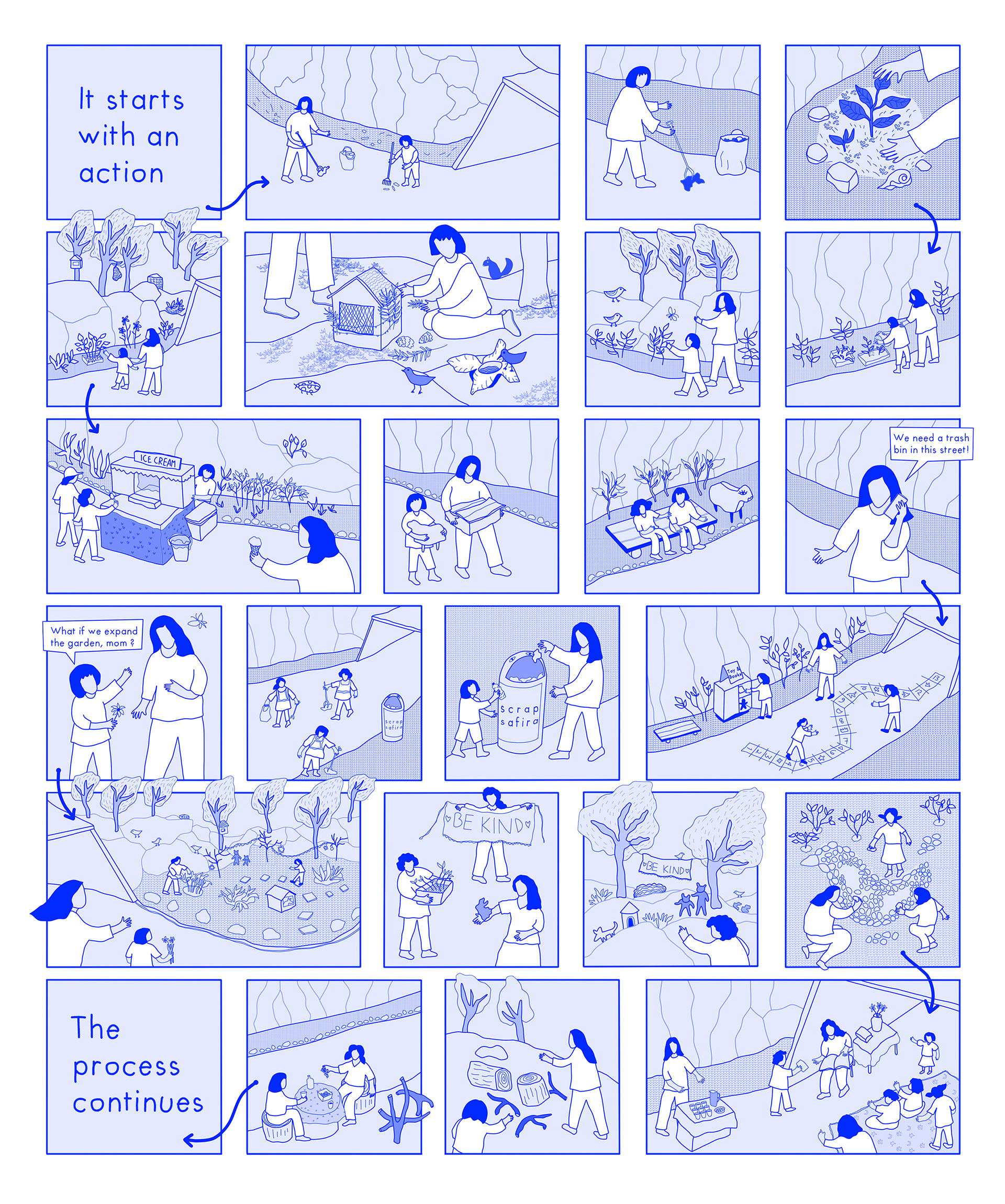

After planting flowers, edible crops, and building benches from recycled wood, Monika and Tristan named the space Safirträdgården, inspired by their street, Safirgatan. They started to organise activities for local children—often with limited resources but abundant creativity. They requested a waste bin from the city and decorated it into a character named Scrap-Safira (who becomes happy when people “feed” it garbage), to encourage proper waste disposal.

Following a learning-by-doing approach, they engaged children in activities such as litter hunts and neighbourhood clean-ups in a creative and playful manner. The garden’s curation evolved through ongoing cycles of planning, dreaming, and making, gradually expanding to the other side of the nearby tunnel. Neighbours and friends began to contribute by sharing artworks, planting together, and testing new ideas—collectively making the space lively and dynamic. Among the berry bushes and trees, familiar figures beloved by children appeared, including Pippi Longstocking, Mr Nilsson, and Lilla Gubben. Seasonal decorations and themed activities kept the garden engaging and relevant, transforming a once-avoided area into a cherished creative hub.

Today, Safirträdgården serves as a vibrant meeting place, demonstrating how small, consistent, care-full actions can spark meaningful transformation and foster a place-based learning environment.

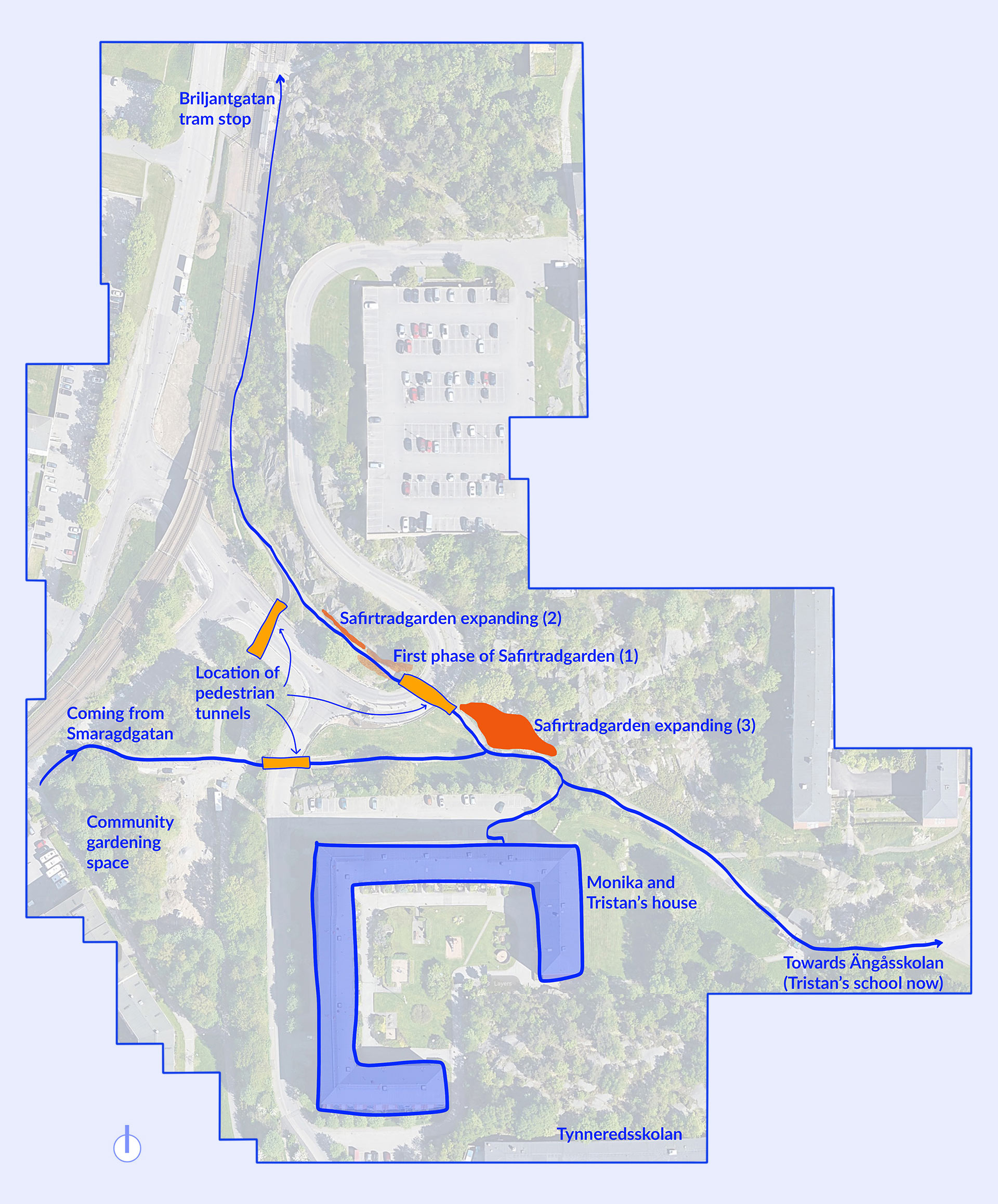

Map showing the location of Safirträdgården in Tynnered. Visualisation: Sadia Sharmin

Visual story portraying the beginning of Safirträdgården. Visualisation: Sadia Sharmin

The concept of curating with care, as articulated by Elke Krasny and Lara Perry (2023), provides a valuable lens for understanding the placemaking and placekeeping practices at Safirträdgården. Rather than treating care as a thematic concern, Krasny and Perry advocate for its integration into the ethics, methods, and relationships that underpin spatial and cultural practices. At Safirträdgården, care is not institutionalised but emerges through sustained, initiator-led acts of holding space. Monika and her son Tristan, the garden’s primary caretakers, have guided its evolution—cultivating opportunities for community interaction, shared memory-making, and ecological learning through intentional design and everyday engagement.

Their approach reflects the principles of placekeeping: sustaining the vitality of a place over time through responsiveness, creativity, and relational commitment. This practice of continuous stewardship and participation manifests through diverse informal activities beyond traditional gardening. These include drawing, painting, reading, planting, cleaning, building garden furniture from reclaimed materials, picnicking, dress-up events, flea markets, music sessions, and animal care. Such hands-on practices transform the garden into an informal learning environment that nurtures curiosity and creativity.

Monika, an avid self-taught gardener with a deep interest in nature and art, works voluntarily as the garden’s principal curator. Her approach blends storytelling with spatial design to spark children’s imagination—for instance, attaching fabric eyes to trees to create “storytelling trees” or placing teddy bears as playful guardians to ignite curiosity. The garden’s aesthetics are often shaped through collective activities such as street doodling, stone painting, or decorating plants with paper snowflakes made by local schoolchildren. Most event ideas emerge through attentive listening to children and parents, and are frequently realised in collaboration with cultural practitioners, including authors, artists, architects, musicians, and youth workers.

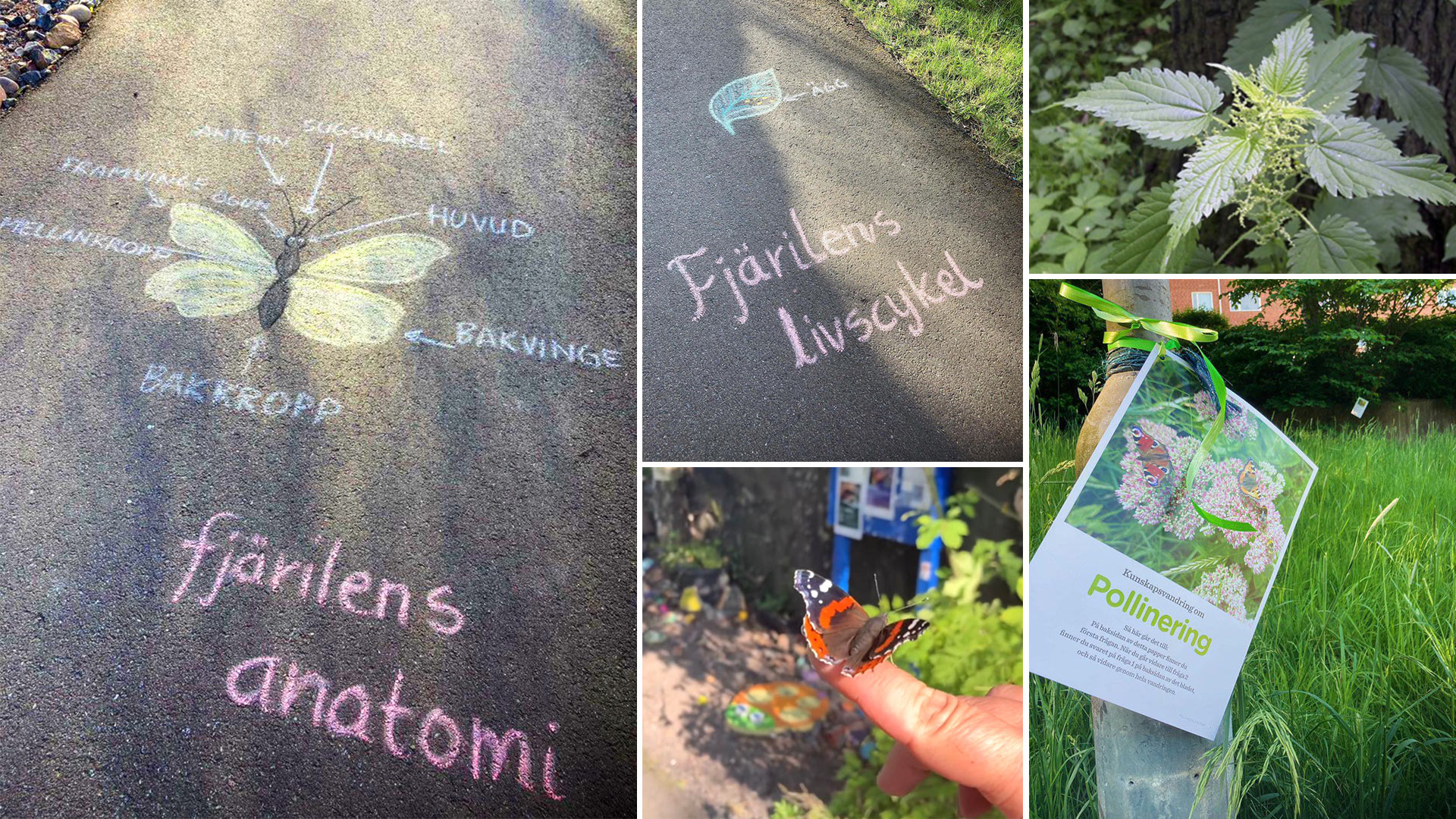

The educational potential of Safirträdgården lies in its playful and experiential approach. For instance, Monika uses butterfly drawings on pavements to introduce the life cycle of insects, prompting conversations about biodiversity, anatomy, and plant-insect interdependence. Quizzes and games rooted in local ecology further embed this knowledge in place-based learning. Seasonal acts like planting tulip bulbs in autumn instil patience and awareness of ecological cycles, while the annual harvest celebration introduces children to food origins through the cultivation of crops like corn, mustard, and wheat. Creative installations that offer apples and nuts to squirrels and birds encourage care for urban wildlife, turning the garden into a refuge for over 20 bird species.

Safirträdgården illustrates how a creative public space can function as a living classroom for environmental learning. Through a curation-with-care approach, it fosters ecological literacy, community bonds, and shared stewardship. As an interstitial space, it transforms everyday encounters into meaningful, place-based insights—deepening participants’ connection to both nature and one another.

Storyboard illustrating the gradual development of Safirträdgården through key moments. Visualisation: Sadia Sharmin

Collage combining illustration and a quiz at Safirträdgården to share knowledge about insect anatomy and the process of pollination. Photo: Monika Tildevik

In conclusion, Safirträdgården stands as a compelling example of how informal learning can flourish beyond traditional settings. Its activities seamlessly integrate environmental education with community action, highlighting a deep interconnectedness of social and ecological systems.

Safirträdgården reminds us that the capacity to imagine and enact change often begins not with grand gestures, but through small, sustained acts of care. It demonstrates how spatial practices rooted in trust, creativity, and collective responsibility can quietly subvert exclusion and nurture futures otherwise overlooked. When care is practised—not performed—it becomes a radical force for environmental and social transformation, capable of turning marginal spaces into sites of possibility.

References

Ardoin, Nicole M., and Joe E. Heimlich. 2021. “Environmental Learning in Everyday Life: Foundations of Meaning and a Context for Change.” Environmental Education Research 27 (12): 1681–1699. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.1992354.

Geertz, Clifford. 1998. “Deep Hanging Out.” The New York Review of Books 45, no. 16, 69.

Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Marsick, V. J., and K. E. Watkins. 1990. Informal and Incidental Learning in the Workplace. London, UK: Routledge.

Marsick, V. J., and K. E. Watkins. 2001. “Informal and Incidental Learning.” New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 2001, no. 89 (2001): 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.5.

Marsick, V. J., and K. E. Watkins. 2018. “Introduction to the Special Issue: An Update on Informal and Incidental Learning Theory.” New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 2018 (159): 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.20284.

National Research Council. Learning Science in Informal Environments: People, Places, and Pursuit. 2009. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12190.

Oakes, L. E., P. E. Hennon, N. M. Ardoin, D. V. D’Amore, A. J. Ferguson, E. A. Steel, and E. F. Lambin. 2015. “Conservation in a Social-Ecological System Experiencing Climate-Induced Tree Mortality.” Biological Conservation 192, 276–285.

Rogoff, Barbara. 1994. “Developing Understanding of the Idea of Communities of Learners.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 1, no. 4, 209–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039409524673.

Sharmin, Sadia. 2024. “In Between Fiction and Reality: Weaving Narratives of Care and Anticipation”. Master’s thesis in Architecture. Chalmers University of Technology.

Tahvilzadeh, Nima. 2021. “Kris och politik mot segregation: Generella eller selektiva åtgärder?” Externa Perspektiv Segregation och Covid-19 Artikelserie 13.

Tidball, K. G., and M. E. Krasny. 2011. “Toward an Ecology of Environmental Education and Learning.” Ecosphere 2, no. 2, 1–17.

Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Watkins, K. E., V. J. Marsick, M. G. Wofford, and A. D. Ellinger. 2018. “The Evolving Marsick and Watkins (1990) Theory of Informal and Incidental Learning.” New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 159, 21–36.

Krasny, Elke, and Lara Perry. 2023. “Introduction.” In Curating with Care, edited by Elke Krasny and Lara Perry, 1–10. London: Routledge.

Learning Practices of Care and Ecology in A British Intentional Community

Ziana S. Madathil

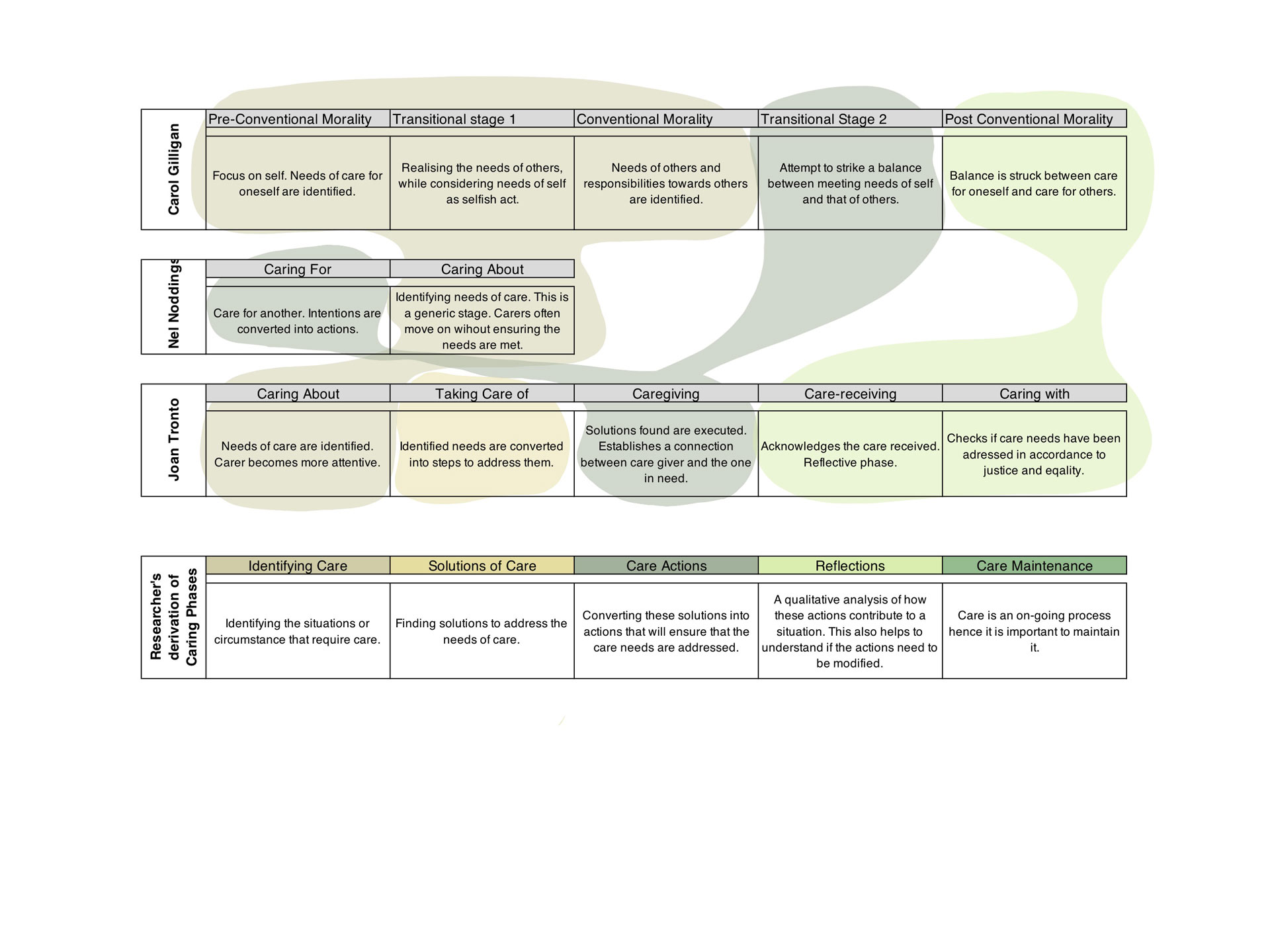

This research investigates the learnings from the impact of care ethics and practices in intentional communities by closely studying a specific British intentional community, The Old Hall, formed in 1974. This paper explores part of my empirical research into social and environmental caring practices in this community with a view to assessing their spatial influence on communal life. The practices in The Old Hall are better understood by critically analysing the care practices elucidated by three care theorists: Carol Gilligan, Nel Noddings, and Joan Tronto. Care ethics are often related to morality, societal issues, and feminism. Gilligan developed her theory on care ethics based on fundamental human relationships in society. She conceives relationships as an essential and vital aspect of human life (Pettersen 2008). Drawing parallels to her theory, Tronto defines ethics of care as an approach to personal, social, moral, and political life that commences from the fact that all humans need care, receive care, and provide care (Tronto 2009). The three of them have been among the earliest to document their ideas about caring practices. Although their theories focus on care from different perspectives, they describe their care theories by outlining phases. While Noddings’ care theories originate from women’s experiences, such as motherhood, which she considers a natural basis for care, Carol Gilligan’s theories differentiate between men and women, proposing that women are more empathetic and responsible than men, who tend to focus more on rules and principles. Conversely, Joan Tronto perceives care more as a moral and political concept, challenging traditional and ideological views of care associated with women. Their contributions towards moral development and caring ethics are explored to comprehend their ideologies and are examined in detail in this paper.

Intentional communities are groups of people living together, leading a lifestyle characterised by shared core values and a common purpose (Kozeny 1995, para 2). Lyman Sargent defines these communities as groups of people who have ‘chosen to live together to enhance their shared values or for some other mutually agreed upon purpose’ (Sargent 1994, p 15). They provide alternative living arrangements that challenge the contemporary social and political habitational structure, establishing inclusive and ecologically resilient ways of living. Such communities are ‘characterized by close relationships, shared common values, and can be found throughout the world in varying degrees of community integration’ (Lulavy 2019). In Britain, intentional communities gained popularity in the 1960s and 1970s. Led by reformer Gerrard Winstanley, the agricultural group of communards known as Diggers experimented with communal living and work, reflecting his social ideology that land should be a ‘common treasury for all’ (Knoppers 2012).

Due to climate change and its consequences, ‘there is growing interest in studying forms of habitation with a smaller ecological footprint and a greater coexistence with nature’ (Escribano, Lubbers, and Molina 2020, p1). Such intentional communities ‘fall within the category of grassroots innovations toward sustainable development’ (Sherry 2019, p1). The ecological practices these communities adopt are adaptative and routed to make a difference. This paper questions how architecture can facilitate learning and sharing ways of embodying the practices of social and environmental care adopted by such shared socio-spatial configurations to address ecological challenges.

Intentional communities and eco-living arrangements are significant steps towards addressing climate change, and ‘architectural design plays a crucial role in this process’ (Amar 2023, p1). Intentional communities are underexplored from an architectural perspective; therefore, this paper analyses the role of architecture in these settings by closely investigating the caring practices in The Old Hall.

Care is an enriching practice experienced by both the provider of the caring deed and the recipient of this deed. It can be described as a way of being that makes life habitable for other people, animals, and the planet. ‘Caring as a situated practice indicates a collective emergent capacity of taking care of and taking care for, a knowing accomplished as ongoing, adaptive, open-ended responses to care needs’ (Gherardi and Rodeschini 2015). Caring ethics strives to maintain relationships in the best possible way while ensuring that both the care-giver and receiver are not compromised in any manner. It is linked to the moral responsibilities that arise from various interdependent relationships that are consequently formed.

Carol Gilligan, Nel Noddings, and Joan Tronto are three feminist theorists who were among the earliest to document care theories and associated them with feminist principles. Berenice Fisher and Joan Tronto identify care as a ‘species activity which includes all the things done to maintain, continue and repair our world so that we live in it as well as possible’ (Fisher and Tronto 1990, p34). According to Noddings, caring is a phenomenon that ‘involves attention, empathetic response and a commitment to respond to legitimate needs’ (Noddings 2010, p28). Although their theories centre on the role of women and their needs, they suggest that care is not a trait defined by gender. ‘Care is a feminist, not a “feminine” ethic, and feminism, guided by an ethic of care, is arguably the most radical, in the sense of going to the roots, liberation movement in human history’ (Gilligan 2014, p101). Feminism, according to Gilligan, is stepping away from patriarchy.

All three theorists have a systematic approach to defining care theories by identifying different phases of care. Based on the similarities in these phases, I have curated a cumulative phase used to analyse the practices in The Old Hall. The phases I have formulated are:

Identifying Care – Care requirements and needs are identified.

Solutions of Care – Developing ways of addressing the identified needs.

Care Actions – Converting the solutions identified in the previous stage into actions.

Reflections – Analysing these solutions to check if they address the needs.

Care Maintenance – Steps taken to ensure continuity in providing and receiving care.

Although Gilligan, Noddings and Tronto mention the need for continuity in the caring process, the three of them do not recognise this as an independent phase of care. Identifying this as a gap, I have included Care Maintenance as the 5th stage.

Analysing Phases of Caring Practices