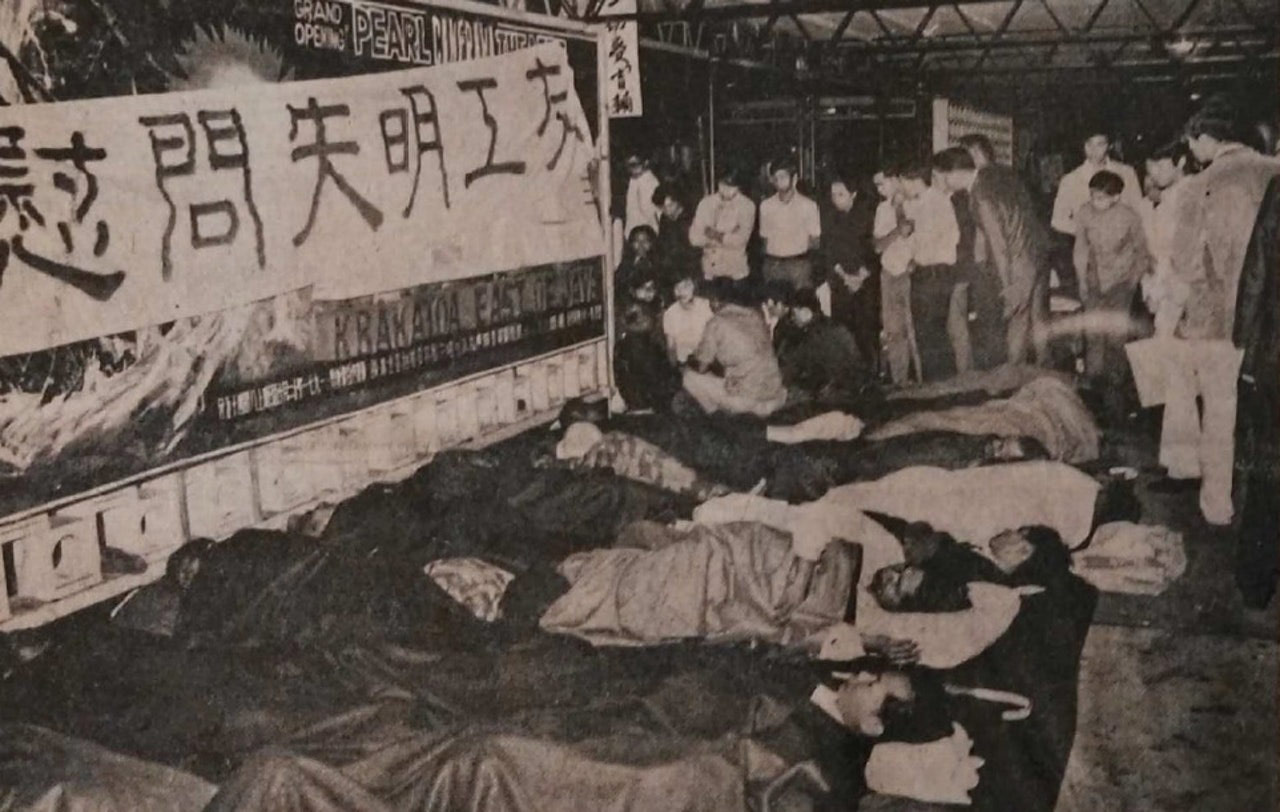

Hong Kong Disability Timeline (1875-2019)

Compiled and Edited by Nanxi Liu

CATEGORY

Most of the textual records are based on existing literature, institutional chronologies, oral history books, news reports and organisation websites, with sources in the footnotes. This is a preliminary record and we hope to expand it in the future.

Regarding the definition of Disability, I have referred to the guidelines of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) and have included various physical and mental Disabilities.

1875

After Hong Kong was colonised by Britain in 1841, no government doctors were employed in the early years. People with mental illness were often deported. Europeans with mental illness were temporarily placed in Victoria Gaol, a prison, before being repatriated to their home countries for treatment. However, “Chinese lunatics” [1] were chained in the dark and distressful cells of Tung Wah Hospital, known as the “Mad House”, without any treatment, waiting to be sent back to China. It was not until 1875 that the British colonial government established the first temporary “lunatic asylum” [2] on Hollywood Road, Hong Kong Island (which later became the Police Married Quarters, now known as PMQ). [3] Around 1880, it was relocated to a site which later became the Government Civil Hospital on the Hospital Road.

1884

The British colonial government established the European Lunatic Asylum. [4]

1891

The Chinese Lunatic Asylum was opened at a lower site (currently the Eastern Street Methadone Clinic) to accommodate Chinese psychiatric patients. [5]

1897

A German Lutheran missionary organisation, the Hildesheimer Blindenmission, sent Ms Martha Postler, a female missionary, to establish the “Tsau-kwong” to provide shelter for four Blind girls. Initially, it only accepted female Blind children and was known as the “Blind Girls’ Home”. [6] Later, it was relocated to To Kwa Wan, Kowloon, at a new facility, which was completed in 1901, accommodating 50 Blind girls. In 1906, a new wing was added to house 20 more Blind girls. [7] In 1913, the construction of the Ebenezer Home for Blind Girls’ permanent campus on Pok Fu Lam Road was completed. During World War I, girls in the Ebenezer Home moved to the Ming Sam School for the Blind in Guangzhou. In 1941, during World War II, the Pok Fu Lam facility was taken over by the Japanese occupation government, and the Blind girls were moved to Kwu Tung in Sheung Shui. Due to outbreaks of lung diseases, malaria, and other infectious diseases, many girls passed away, and only 18 girls survived after the war. In 1948, the Blind girls returned to the Pok Fu Lam facility. [8] Later, the Ebenezer Home for Blind Girls changed its name to the Ebenezer School & Home for the Visually Impaired.

1906

The British colonial government passed the “Asylums Ordinance”. It was the first time that the detention and care of people with mental illness was formally legislated. The separate “asylums” for Westerners and Chinese were merged into the Victoria Mental Hospital, which was affiliated with the National Hospital. It had four male wards and one female ward, with a total of 84 beds. Treatment services were provided by a part-time general physician. The government had no plans to expand psychiatric services, as it considered many patients to be temporary residents of Hong Kong and believed that some could be sent to the John G. Kerr Refuge for the Insane in Fangcun, Guangzhou, for treatment. This transfer collaboration with the John G. Kerr Refuge for the Insane stopped in 1949 when the People’s Republic of China was established. [9]

1933

Hong Kong residents Lee Luk-wah and Chan Lai-fong travelled to Yantai, China, to attend a teacher training programme at the Yantai School for the Deaf. In September 1935, with church support, they founded the Hong Kong School for the Deaf (Chun Tok School), the first special school for Deaf students in Hong Kong. During the Japanese occupation, the school was closed for seven years. It reopened in 1948 and continued operation until 2004, when it stopped admitting Deaf students and converted into a mainstream school. The school emphasised oral and lip-reading education, and sign language was strictly prohibited. If students were caught using sign language, teachers would write their names on a piece of paper, hang it around their necks with a rope, and make them stand in the hallway as punishment. Apart from the Chun Tok School, there were three other Deaf schools, all founded by foreign missionaries: Kai Shing School, Caritas Magdalene School and the Lutheran School for the Deaf. All of these Deaf schools focused on oral education, with only the Lutheran School for the Deaf incorporating a small amount of sign language. [10]

1948

A Deaf educator, Mr Chan Cheuk-cheung, founded the Overseas Chinese School for the Deaf and Dumb on Hong Kong Island, introducing Shanghai Sign Language to Hong Kong. [11] In 1956, a branch was established in Kowloon, using sign language as the primary mode of instruction. However, the school closed between 1975 and 1976. Later, several of its teachers joined the Deaf Children’s Society, which was run by the Social Welfare Department, and other teachers transferred to other Deaf schools. As a result, Shanghai Sign Language was spread to different Deaf communities in Hong Kong. [12]

1954

The Mental Health Association of Hong Kong was officially established. The founders included Professor Yap Pao-meng, Hong Kong’s first psychiatrist, and Dr Irene Cheng, a scholar. [13]

1956

The Hong Kong Society for the Blind was established, modelled after the Royal National Institute for the Blind (RNIB) in the UK. It opened seven vocational training centres that provided traditional job training for visually impaired people. [14]

1959

New Life Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association was founded by Dr Stella Liu, the first female psychiatrist in the Victoria Mental Hospital, along with a group of people in recovery (PIR) of mental illness. Originally named the New Life Mutual Aid Club, it was reorganised in 1965 and renamed the New Life Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association. [15]

The Hong Kong Society for Rehabilitation was founded in 1959 by orthopaedic surgeon Dr Harry Fang Sin-yang. Initially, the concept of “rehabilitation” was aimed at people injured in industrial accidents during the 1950s and 1960s. [16]

1961

Castle Peak Hospital, a psychiatric hospital, opened. [17]

1962

The Hong Kong Society for Rehabilitation opened Hong Kong’s first rehabilitation hospital, which was also considered then the first accessible building in Hong Kong. [18]

1963

The Hong Kong Association for the Spastic Children was founded in 1963 by Dr Elaine Field, Professor in Paediatrics at The University of Hong Kong, and other professionals. It provided education and care for children with cerebral palsy. As services expanded to people of different ages, the organisation removed the word “Children” from its name in 1967, renaming it The Spastics Association of Hong Kong. In 2008, it was officially renamed the SAHK. [19]

The Hong Kong Society for the Blind established Asia’s first Sheltered Workshop for the Blind and set up a hostel for blind workers nearby. [20]

1964

A group of young blind people graduated from the Ebenezer School & Home for the Visually Impaired and became Hong Kong’s first blind manufacturing workers in the sheltered workshop for the blind [21] and telephone operators. Dissatisfied with the government and the Hong Kong Society for the Blind’s control over services for the blind, as well as the social discrimination and unfair treatment they faced, a group of blind people came together to establish Hong Kong’s first self-help organisation for people with Disabilities called the Hong Kong Blind Friends’ Club (HKBFC). This was the first organisation in Hong Kong that was organised and managed by the blind. Initially, they rented a rooftop classroom as a gathering place for blind people, organising activities such outings, a Chinese and Western music band, and singing competitions. In 1975, the organisation was renamed the Hong Kong Blind Union, emphasising advocacy for rights as their primary mission. [22]

1968

The Hong Kong Society for the Deaf was founded in 1968 by Dr George Choa Wing-Sien, Hong Kong’s first ENT (ear, nose and throat) specialist, along with other professionals and parents. [23]

The New Life Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association (NLPRA) developed both agricultural and industrial ‘Sheltered Workshop’ services. They rented farmland near the Castle Peak Hospital to establish the New Life Farm, which became Hong Kong’s first and only agricultural Sheltered Workshop. From NLPRA’s definition “Sheltered workshops provide people in recovery of mental illness and people with disabilities with a working environment specially designed for vocational training through an income-generating work process.” [24] Meanwhile, the first industrial Sheltered Workshop was set up in a male halfway house. [25]

1970

The Hong Kong Federation of Handicapped Youth was founded as a government registered charitable organisation managed by people with Disabilities. [26]

1971

Blind Workers Strike

Workers at the Hong Kong Factory for the Blind in To Kwa Wan protested against unreasonably low wages (ranging from HK$2 to HK$4 per day) and poor working conditions. Over 200 workers (out of around 300 in total) joined the strike and staged a sit-in protest at the Star Ferry Pier. The strike received support from student organisations, religious groups, and members of the City Council. On October 7, 1971, the Hong Kong Society for the Blind’s management unilaterally ended negotiations, triggering further discontent among Blind workers, who then staged another sit-in outside the factory. As a result, the chairman of the Hong Kong Society for the Blind, Arnaldo de Oliveira Sales, stepped down and workers successfully negotiated wage adjustments. [27]

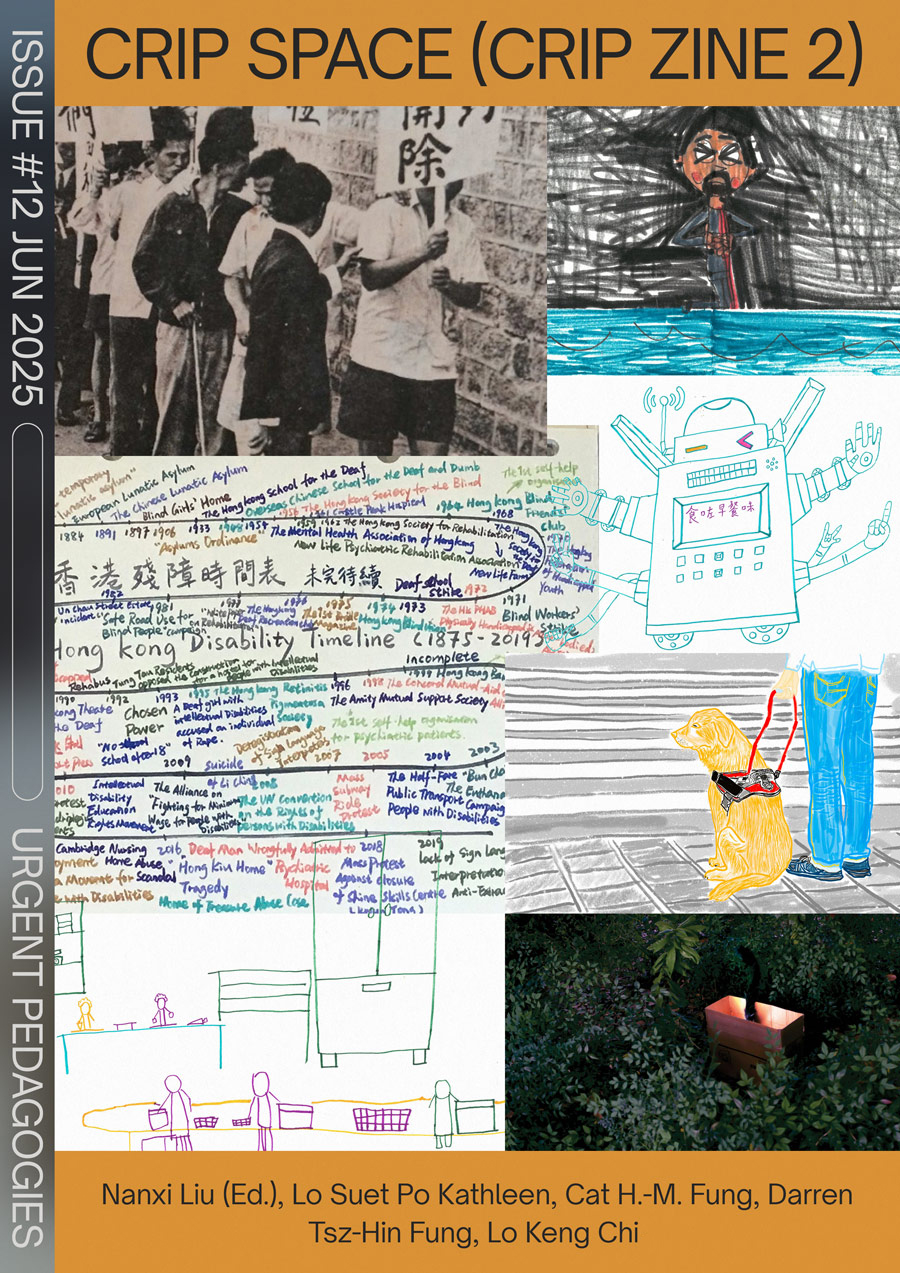

An old news photo showing the Blind Workers Strike at the Star Ferry Pier, November 1971. Photo from Government Records Service of Hong Kong.

1972

The Hong Kong PHAB (Physically Handicapped and Able-Bodied) Association was established, inspired by the concept “PHAB (stands for Physically Handicapped and Able-Bodied)” in the UK in the 1950s. The term “PHAB” represents the integration and equal participation of both people with Disabilities and able-bodied individuals. In the 1970s, the founder of the UK PHAB Association, Mrs Mary Robinson, introduced the concept of “Opportunity Not Pity” to Hong Kong. [28]

Due to internal disagreements within the Hong Kong Blind Friends’ Club regarding whether to help the Blind workers’ strike, and the executive committee of HKBFC not giving direct support to the Blind workers, some committee members left and formed a new organisation, The Hong Kong Federation of the Blind. [29]

1973

Deaf School Strike

50 students from the Hong Kong School for the Deaf (Chun Tok School) hung large banners during lunchtime with black Chinese characters on white cloth, displaying slogans such as “Strike” and “We Demand Sign Language”. They protested against the school’s strict oral-only teaching policy and demanded sign language education. [30]

The Hong Kong Society for the Blind established Hong Kong’s first Braille and Talking Book Library with a Talking Book Production Studio. [31]

1974

Two representatives from the Hong Kong Blind Friends’ Club, Lee Bobby and Chau Yin-hang, attended the 2nd International Federation of the Blind Conference. They learned about the global blind community’s self-advocacy movements and realised that, unlike in Hong Kong, blind people in Western countries could become lawyers, teachers, and scientists. Upon returning to Hong Kong, they strategically shifted their advocacy efforts. Instead of just criticising the government, they actively shared success stories from abroad. This inspired some employers to proactively reach out to blind organisations and offer jobs to blind people. Influenced by the Western Disability rights movement, they proposed renaming the Hong Kong Blind Friends’ Club to Hong Kong Blind Union, with a stronger focus on fighting for rights. [32]

1975

The first Braille magazine, Advocacy Quarterly, was published (later evolving to become The Voice). However, due to high printing costs and the limited Braille literacy among newly Blind members, Advocacy Quarterly was discontinued after two years, with the fourth issue published in 1977. [33]

1976

The Hong Kong Deaf Recreation Club was established by a group of volunteer Deaf people. In 1978, it was renamed as the Hong Kong Deaf Recreation Association, and between 1986 to 1988, it was officially renamed the Hong Kong Association of the Deaf, emphasising sign language, autonomy, and Deaf identity. [34]

The Hong Kong Society for the Deaf suggested to the government that Deaf people should be included as “people with Disabilities” in the 1976 mid-year population census. [35]

The Hong Kong government published its first Hong Kong Rehabilitation Program Plan (RPP). [36]

1977

The Hong Kong government released the “White Paper on Rehabilitation: Integrating the Disabled into the Community: A United Effort”. [37]

1978

The Hong Kong Blind Union transformed its first Braille periodical into the world’s first Cantonese audio magazine entirely produced by Blind people, called The Voice. It featured news, music performances, radio dramas, and discussions on global issues affecting visually impaired communities. [38]

The Hong Kong Deaf Recreation Association (later became Hong Kong Association of the Deaf) held a Deaf studies meeting in The Hong Kong Council of Social Service, as a campaign for Disability allowances for Deaf people. [39]

The Hong Kong Society for Rehabilitation launched Hong Kong’s first accessible transport service Rehabus, which initially operated two vehicles. [40] By 2023, the fleet had grown to 204 buses, however in 2024, there were over 20,000 reported cases of service refusals. [41]

1981

“Safe Road Use for Blind People” Campaign

The Hong Kong Blind Union published the “Declaration of the Rights of the Blind” and a report on education recommendations. They organised protests to raise public awareness about the safety challenges blind people faced when using pedestrian pathways. According to the 50th anniversary commemorative book published by the Hong Kong Blind Union: “[In 1981] The MTR had just begun operations but did not accommodate people with Disabilities. Few pedestrian crossings had auditory signals for visually impaired people. Sidewalks were full of hazards, including uncovered roadworks and illegally parked vehicles. To address this, the Blind Union launched the ‘Safe Road Use for Blind People’ campaign, where members placed warning stickers on illegally parked cars to raise public awareness. Additionally, they designed bus route number cards to help blind people identify and board the correct buses.” [42]

The Kwai Chung Hospital, a psychiatric hospital, was established. [43]

1982

Un Chau Street Estate Incident: “Anne Anne Kindergarten Stabbing”

A tragic incident at the Anne Anne Kindergarten in Un Chau Street Estate shocked Hong Kong. A man with mental illness attacked children in a public housing estate, leading to widespread fear and discrimination against psychiatric patients. In response to public pressure, leading psychiatrists in Hong Kong introduced the Priority Follow-Up (PFU) system, which categorised certain psychiatric patients as high-risk for violent relapse. This system extended hospital stays for some patients, imposed stricter discharge procedures and was based more on social concerns than medical evidence, reinforcing negative stereotypes about mental illness. [44] This incident inspired the 1986 film The Lunatics, which was criticised for stigmatising psychiatric patients.

1983

Following the Un Chau Street Estate Incident, the government decided to build more halfway houses for psychiatric patients in public housing estates. However, residents of Sha Tin’s Sun Chui Estate strongly opposed the plan. At a community meeting attended by government officials and the New Life Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association, some residents threw dead rats to protest against the halfway house. [45] After two years of public education efforts, the Sun Chui halfway house finally opened in 1986. Before 1982, Hong Kong had only six halfway houses. After the Un Chau Street Estate Incident, the number increased to over twenty in a short period. [46]

1986

The Direction Volunteer Service for the Handicapped was founded. The founder met a group of severely physically Disabled patients who had no family members and friends and visited them. The society’s ignorance of their needs invoked their self-pity. They came together to form Direction Volunteer Service for the Handicapped to strive for their own welfare, resources and opportunities. In 1991, Direction Volunteer Service was officially registered as a non-profit-making association and in 1994, became a member agency of the Hong Kong Community Chest. In 1995, it changed its name into the Direction Association for the Handicapped. Since April 1, 2006, the Association operates as a limited company. [47]

The Hong Kong Joint Council of Parents of the Mentally Handicapped was founded. In the early 1980s, there was a severe shortage of services for adults with intellectual Disabilities. Thousands of special school graduates stayed at home, unable to apply their education and skills. In 1986, a group of parents of children with intellectual Disabilities formed a self-help group to advocate for their children’s rights. [48]

Kwok Ah-Nui Incident

The media exposed the case of six-year-old Kwok Ah-Nui, who was allegedly imprisoned by her mother, who had mental illness, in a public housing unit in Kwai Hing Estate. The Social Welfare Department, together with the Royal Hong Kong Police Force, Fire Services Department, District Office, and Housing Authority, broke into the home and took the girl to a children’s home, while her mother was forcibly admitted to Kwai Chung Hospital for psychiatric treatment. The Social Welfare Department’s actions were heavily criticised as an abuse of power. [49]

The Parents’ Association of Pre-School Handicapped Children was founded from a support group formed by parents of Disabled children. It was registered as a non-profit charitable organisation in 1987 and later became a registered company in 2001. [50]

Arts with the Disabled Association Hong Kong was formed as a non-governmental organisation in 1986, following the success of the first Hong Kong Festival of Arts with the Disabled. [51]

1987

The Hong Kong Blind Union established the “Peach Garden Theatre”, a theatre group for visually impaired performers. The name symbolises “brotherhood and unity” which was inspired by “The Oath of the Peach Garden” in the 14th-Century Chinese novel Three Kingdoms. [52]

The government attempted to redefine “Mental Disorder” in July 1987. The government submitted the Mental Health Amendment Bill to the Legislative Council, proposing to include people with intellectual Disabilities under the definition of “mental disorder”. This sparked outrage and fear among parents of children with intellectual Disabilities, who strongly opposed the amendment. [53]

1988

Blind Cyclists’ Fundraising Ride to Guangzhou

The Hong Kong Blind Union organised a charity cycling event where Blind participants rode to Guangzhou to raise funds for the Guangzhou Blind Children’s School Library. The funds were later expanded to support assistive devices and benefited two other Blind schools in the Guangdong Province. [54]

1989

Opposition to a Rehabilitation Centre in Kwun Tong

The Mental Health Association of Hong Kong proposed a multi-purpose rehabilitation centre in Kwun Tong, but local district council members and residents strongly opposed it, leading to the project being suspended. [55]

Inspired by the 1986 visit of the National Theatre of the Deaf (USA) to Hong Kong, the Hong Kong Theatre of the Deaf was established. [56]

Residents of Cho Yiu Chuen, Kwai Chung, opposed the opening of a hostel for people with severe intellectual Disabilities in their neighbourhood. In response, the Hong Kong Joint Council of Parents of the Mentally Handicapped launched the campaign “People with Intellectual Disabilities Are Human Too”, condemning the discriminatory attitudes of the residents. [57]

1990

Rehabus refused to serve people with intellectual Disabilities. [58]

Residents of Fortress Hill, North Point, opposed the establishment of a special school in their district. [59]

1992

Residents of Tung Tau Estate, Wong Tai Sin, opposed the construction of a hostel for people with intellectual Disabilities in their estate, delaying the project. [60]

For the first time, four people with intellectual Disabilities and one parent were supported by volunteers to attend the International Self-Advocacy Conference in Canada. They were inspired by the People First movement, which was founded in Sweden in 1968. [61] In 1993, they attended another international conference in Toronto. In 1994, they formed a preparatory committee for a Hong Kong self-self group called Chosen Power, Asia’s first self-help group organised by people with intellectual Disabilities. [62]

1993

Residents of Laguna City, Lam Tin, protested against the construction of a day care centre for people recovering from mental illness in their neighbourhood. [63]

In September, a Deaf girl with intellectual Disabilities testified in court, accusing an individual of rape. However, on the sixth day of the trial, the survivor broke down in tears due to stress, and Judge Woo Kwok-hing decided to terminate the hearing, leading to the immediate release of the defendant. This case sparked public outcry, and the Hong Kong Joint Council of Parents of the Mentally Handicapped, along with other parent groups and social organisations, launched the Equal Justice for All campaign, demanding reforms in the legal system to ensure fair trials for people with Disabilities. [64] As a result, the Chief Justice appointed Judge Wang Kin-chau to lead a cross-departmental working group, which spent over 10 months developing 17 recommendations to assist people with intellectual Disabilities for testifying in court. In 1994, the working group introduced special procedures for vulnerable witnesses, including: allowing pre-recorded testimonies; providing trained interpreters or facilitators; and modifying courtroom questioning styles to be more accessible.

Sign language research and training programmes started at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Decades of research efforts made the university become renowned for being the first academic institution in the Asia-Pacific region to specialise in sign linguistics research and Deaf training. [65]

1995

The Hong Kong Retinitis Pigmentosa Society, a self-help organisation for people with retinal degenerative diseases, was founded in March 1995. In 2002, it was renamed to Retina Hong Kong to serve people with hereditary blindness-related conditions. [66]

The Direction Volunteer Service for the Handicapped was renamed the Direction Association for the Handicapped, becoming Hong Kong’s first organisation for people with spinal cord injuries and quadriplegia. [67]

A patient-led organisation called Care for Your Heart was founded by heart disease patients and their families. [68]

The Hong Kong government released the second “White Paper on Rehabilitation–Equal Opportunities and Full Participation: A Better Tomorrow for All”. [69]

1996

The Amity Mutual Support Society was established as Hong Kong’s first self-help organisation for psychiatric patients. [70]

A baker was accused of raping a woman with intellectual Disabilities, but the case was dropped because the victim was unable to undergo cross-examination. [71]

1997

The Hong Kong Blind Union developed the first Cantonese screen-reader software for DOS-based computers. However, it could only read text files and could not allow users to fully navigate the computer interface. [72]

1998

A self-help group for people recovering from mental illness, the Concord Mutual-Aid Club Alliance, was officially registered as a non-profit organisation. In 2002, it was recognised as a charitable institution by the Inland Revenue Department. [73]

Since most services for the visually impaired were concentrated in Kowloon, the organisation Care the Visually Impaired was founded to provide services specifically for visually impaired people living on Hong Kong Island. [74]

The Hong Kong Neuro-Muscular Disease Association was founded, as a self-help organisation for people with neuromuscular disorders and their families. [75]

1999

The Hong Kong Bauhinias Deaf Club, Hong Kong’s first self-help group for gay and lesbian Deaf people, was founded. [76]

The Hong Kong government’s Labour and Welfare Bureau introduced the Disability Registration Card, commonly known as the “White Card”, for people with Disabilities residing in Hong Kong. However, many people in Hong Kong believe that the “White Card” users are people with mental illness, more and more people use the term “White Card” to ridicule people whose behaviour is different from “normal”, and it has become one of the terms used to stigmatise psychiatric patients and people with Disabilities. [77]

2000

The Association of Women with Disabilities Hong Kong, was established as Hong Kong’s first self-help organisation advocating for the rights of women with Disabilities. However, due to a lack of a new executive committee, it dissolved in November 2022. [78]

The Theatre of the Silence was founded by a group of hearing impaired theatre artists in Hong Kong. [79]

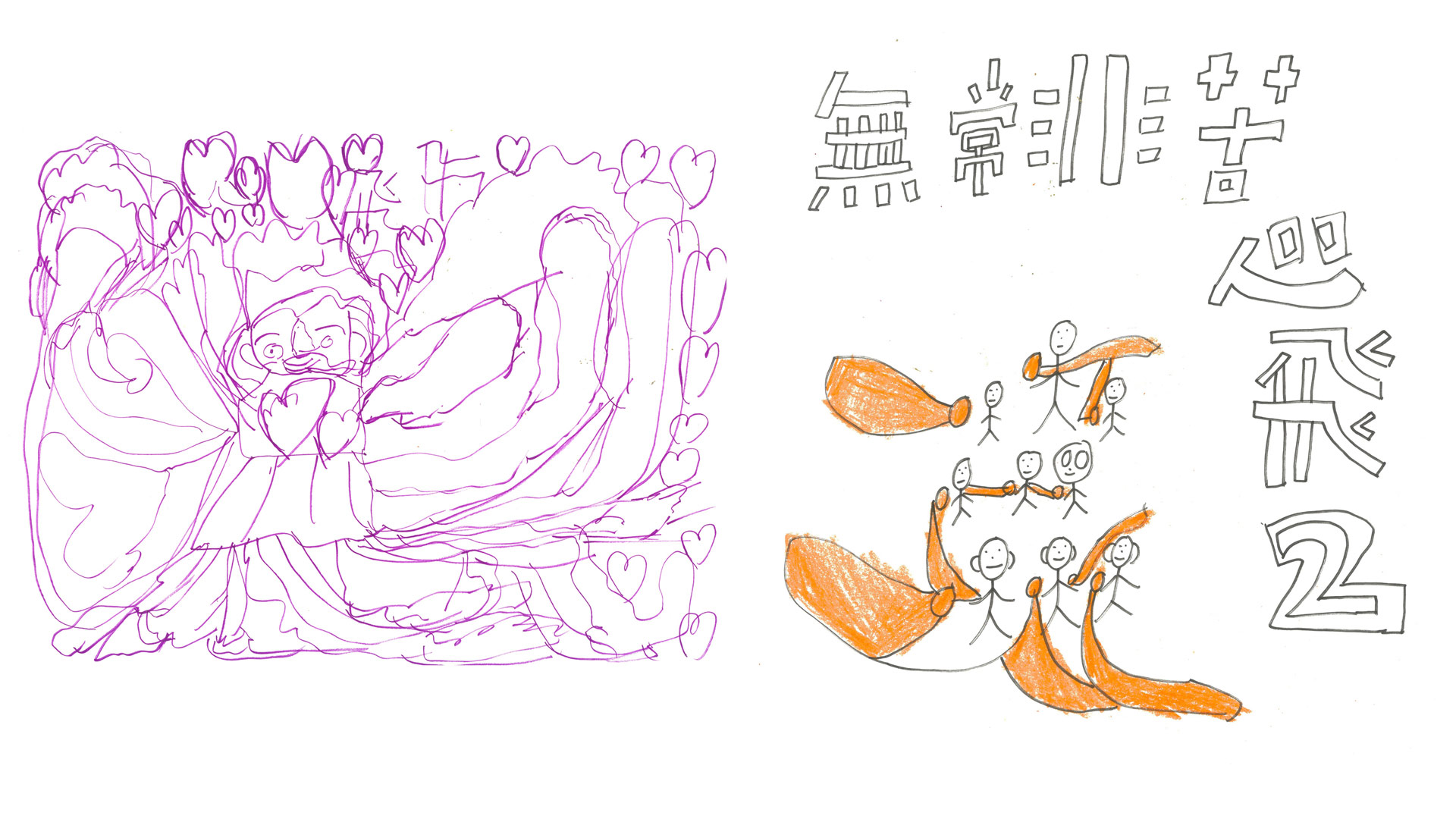

Dancing Heart Troupe, drawing by Lai Yee (left) and Vincent (right) @weighty.design.studio, St James’ Settlement. Image courtesy of Weighty Design Studio

Dancing Heart Troupe was established by the St. James’ Settlement for mainly people with mild intellectual Disabilities and Down syndrome. [80]

On August 24, Yu Man-hon, a 15-year-old boy with autism and intellectual Disabilities, went missing. He was originally travelling home with his mother on the MTR. At Yau Ma Tei Station, he suddenly left the train. Surveillance footage showed him arriving at the Lo Wu border checkpoint at 1:29 PM. Immigration officers, mistaking him for a Mainland Chinese citizen, sent him across the border to Shenzhen. He was never seen again. [81]

2003

“Bun Chai” (Tang Siu-bin) and the Euthanasia Debate

Mr Tang Shiu Bun, known as “Bun Chai”, became quadriplegic following an accident in 1991. After 12 years of suffering, he wrote a letter to then Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa, requesting euthanasia. His request sparked a major public debate—not about euthanasia itself, but about the government’s neglect of people with severe Disabilities. Due to public pressure, the government introduced a monthly caregiver allowance of HK$1,115 for eligible quadriplegic patients, with a maximum reimbursement of HK$4,296 per month. Bun Chai later moved out of the hospital into public housing, with all medical and caregiving expenses covered by the Social Welfare Department. [82]

The Chinese University of Hong Kong officially established The Centre for Sign Linguistics and Deaf Studies in November. [83]

2004

The Half-Fare Public Transport Campaign for People with Disabilities, a coalition of over 40 Disability organisations launched a campaign to demand half-price public transport fares for people with Disabilities. During 2005-2006, they held large-scale assemblies and a city-wide petition collecting 40,000 signatures. In 2009, the MTR introduced fare discounts for people with Disabilities. In 2012, the HK$2 Public Transport Scheme for eligible Disabled people was implemented—after eight years of advocacy. [84]

2005

Mass Subway Ride Protest

700 people with Disabilities participated in a protest ride on the MTR, demanding fare discounts and better accessibility measures. [85]

2007

Deregistration of Sign Language Interpreters

The Hong Kong Council of Social Service suspended the registration system for sign language interpreters, citing the low pass rates in qualification exams. As a result, for the next nine years, Hong Kong had fewer than 10 officially recognised sign language interpreters, creating severe shortages in legal and public service settings. Meanwhile, the judiciary maintained a separate list of 11 part-time sign language interpreters, who provided exclusive services for court cases. The Hong Kong Police Force also relied on the same limited group of interpreters. [86]

2008

Hospital Authority Introduces Free Sign Language Interpretation

The Hospital Authority began offering free sign language interpretation for public hospitals and clinics. However, many Deaf patients and medical staff were unaware of the service. In 2017, a Deaf person named Chun Yi Connie Lo, reported that she requested sign language interpretation five times in the emergency room but was denied each time. [87]

A group of Deaf people dedicated to promoting sign language established the Hong Kong Sign Language Association. [88]

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities took effect in China and Hong Kong on August 31. [89]

Suicide of Li Ching

The suicide of Li Ching, a hard-of-hearing person, raised public awareness about employment discrimination against Deaf and hard-of-hearing people. Her sister, Li Lai, along with other volunteers, founded Silence, a comprehensive support centre for Deaf and hard-of-hearing people. [90]

2009

The Alliance on “Fighting for Minimum Wage for People with Disabilities”

Disability rights advocates opposed the government’s plan to assess Disabled workers separately under the Minimum Wage Ordinance. At the time, Sheltered Workshop participants received only HK$21 per day in “training allowances” (which increased to HK$26.5 in 2014). The average monthly pay was just HK$850. By 2009, only 13.2% of working-age Disabled people were employed, yet the minimum wage law offered no guaranteed protections for them and allowed employers to justify lower wages through “disability assessments”. [91]

“No School After 18” – Intellectual Disability Education Rights Movement

In April 2009, the Education Bureau verbally notified all special schools that unless a student formally applied for an extension, they would be forced to leave at the age of 18, regardless of whether they had completed 12 years of education. This triggered the “No School After 18” Intellectual Disability Education Rights Movement, Hong Kong’s first major legal battle for Disability education rights. On May 26, parents formed the Grand Alliance for Special Education Rights and held a protest assembly, condemning the lack of consultation before implementing the policy. On June 25, Tang Wai-ting, a student with intellectual Disabilities, filed a judicial review against the Education Bureau, citing violations of the Disability Discrimination Ordinance and the UNCRPD. On August 24, The High Court rejected Tang’s case, ruling that the policy did not constitute discrimination. On August 31, nearly 100 students with intellectual Disabilities and their parents protested in Central, demanding the right to continue their education. Tang Wai-ting appealed the case and filed a complaint with the Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC) in October. The Education Bureau reversed its policy, removing the age limit and increasing funding for special schools in November. [92]

Symbiotic Dance Troupe

A diverse dance troupe was founded, featuring performers with mobility impairments, visual impairment, Deafness, and intellectual Disabilities. [93]

Introduction of Audio Description for the Blind

The Hong Kong Society for the Blind began promoting audio description services for films. In 2010, Hong Kong held its first public cinema screening with live audio description, featuring the film Team of Miracle: We Will Rock You. [94]

2010

Short Press – A Mental Health Advocacy Publication

A group of psychiatric survivors self-published a magazine called Short Press, challenging the medicalisation of mental illness and exposing the collusion between psychiatry and the pharmaceutical industry. The magazine argued that mental health issues should be understood as social oppression rather than purely medical conditions. It was first published in April, with 2,000 copies printed. They carried a banner that said “Grassroots Psychiatric Patients Demand the Right to Public Spaces” during the protest in the Half-Fare Public Transport Campaign for People with Disabilities. [95]

Vancouver International Deaf Education Conference

The Vancouver International Deaf Education Conference formally acknowledged and overturned the infamous 1880 Milan Congress decision, which had banned sign language in Deaf education worldwide. Hong Kong’s Deaf community celebrated this milestone. [96]

The Hong Kong TransLingual Services (HKTS) was established and has since become the interpretation service contractor for public hospitals and clinics under the Hospital Authority. As of May 2020, HKTS has only 16 interpreters who can provide sign language interpretation services, and all of them are employed on a freelance basis. Interpreters are not required to be on-call at all times and will take cases when available and decline when unavailable. Interpreters in hospitals are paid at a lower hourly rate of HK$100-$200 per hour, whereas the rate for court-appointed sign language interpreters is more than HK$300 per hour. [97]

The First Hong Kong International Deaf Film Festival

On September 17, 2010, Hong Kong hosted its first international film festival dedicated to Deaf cinema. This festival was co-organised by the Hong Kong Association of the Deaf, the Asian People’s Theatre Festival Society, Hong Kong Arts Centre and City University of Hong Kong. [98]

Bed Protest by Quadriplegic Patients

On November 14, a group of quadriplegic patients held a protest march while lying on hospital beds, demanding better healthcare, nursing, and caregiving subsidies. [99]

2011

Mental health activists from Short Press joined the July 1 Protest with the banner “Psychiatric Patients Demand the Right to Public Spaces”. They later published their second issue of Short Press in August. [100]

2012

Introduction of Guide Dogs to Hong Kong

The first guide dogs were introduced from the United States. However, by October, two of Hong Kong’s first guide dog users faced severe discrimination: MTR staff, shopping malls, and restaurants refused to let them enter with their guide dogs. Lane Crawford Harbour City’s security guards demanded that the blind people wear identification labels and that their guide dogs wear masks to “reassure other customers”. [101]

2013

“Chun Tok School Incident” – Abuse Allegations at Deaf School

Former students of Chun Tok School revealed extensive abuse, including bullying, physical punishment, and sexual violence from teachers. This led to the formation of several Deaf advocacy groups to monitor and investigate the case. [102]

Theatre in the Dark

Blind theatre artist Chan Hin-wang founded Theatre in the Dark, which uses complete darkness to create immersive theatrical experiences that go beyond visual storytelling. [103]

Deaf Protest Against Lack of Sign Language in News Broadcasts

On December 27, three Deaf people—Cheung Yin-fan, Tiu Hiu Lan and Wong Keung—filed a formal complaint with the Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC), demanding that TV news should provide sign language interpretation. However, when the Deaf activists arrived at the EOC headquarters, they discovered that the commission itself had failed to arrange any sign language interpreters, ironically discriminating against the very people filing a discrimination complaint. [104]

2014

Five-Year Protest Against Mental Health Centre in Sha Tin

Residents of Mei Wai House, Sha Tin, protested for five years against the establishment of a mental health centre in their neighbourhood. The centre was finally approved in 2019. [105]

Protest Against the Closure of the Sign Bilingual Education Programme

In June, the Sign Bilingual and Co-enrollment in Deaf Education Programme, developed by the Centre for Sign Linguistics and Deaf Studies at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, was set to lose its seven-year funding from The Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust. Despite its success, the Education Bureau refused to provide funding, leading to the closure of the primary school section. The advocacy group Deaf Power organised a protest march from Chater Garden to the government headquarters, demanding that the government support sign bilingual education. Around 250 protesters participated, holding banners and chanting “Sign Language Education is the Government’s Responsibility”. A short play was performed to highlight how the lack of sign language education forces Deaf people into social exclusion. [106]

Sign Language Interpreters Volunteered During the Umbrella Movement

During the Umbrella Movement from September, a group of sign language interpreters voluntarily provided real-time interpretation for Deaf protesters at demonstration sites. They also launched the “Occupy Sign News Initiative” on Facebook, where they interpreted key terms such as “civil nomination”, “NPC Standing Committee”, and “civil disobedience” into Hong Kong Sign Language. [107]

Concerning Home Care Service Alliance

The Concerning Home Care Service Alliance was formally established on May 31, and in May 2020, it officially became a tax-exempt charitable organisation. The alliance was formed by more than 10 groups of elderly people and people with Disabilities, non-governmental organisations and frontline social work organisations, with the aim of focusing on the problems of home care services, such as long waiting times, bundling of services, severe service workforce shortage, mismatch of service resources, lack of short-, medium- and long-term planning, etc. [108]

2015

Employment Quota Movement for People with Disabilities

The Alliance on Employment Quota System of Persons with Disabilities was formed by over 30 Disability self-help and rehabilitation groups. They advocated for a mandatory employment quota system requiring public and private organisations to hire a set percentage of Disabled employees. They proposed progressive measures to ensure that Disabled people with work capabilities have access to jobs. [109]

Cambridge Nursing Home Abuse Scandal

A luxury elderly care home in Tai Po, Cambridge Nursing Home, was exposed for abusing elderly residents by stripping them naked on the terrace before bathing them—a violation of human dignity. In 2023, a Hong Kong film In Broad Daylight was made based on this scandal. [110]

The Audio Description Association (Hong Kong) was established to promote audio description services for visually impaired people. [111]

2016

Hong Kong “Hong Kiu Home” Tragedy

Hong Kiu Home, a private care home for people with Disabilities, was shut down after its founder was accused of sexual assault. Founder Cheung Kin-wah, a registered social worker, had previously been arrested in 2014 for sexually assaulting three female residents with intellectual Disabilities. Similar accusations had been made against him as early as 2002, but the case was dropped due to “witness incompetence”. Several unresolved deaths had occurred at the home, including a 14-year-old autistic boy who jumped out of a window. On October 20, the Social Welfare Department officially revoked Hong Kiu Home’s licence, making it the first private care home to shut down under the new licensing system. On the same night, over 500 people gathered outside the Social Welfare Department headquarters, demanding long-term reforms in the care home system, judicial processes, and staff qualifications. This tragedy was adapted into the film In Broad Daylight (2023). [112]

Home of Treasure Abuse Case

Another care home for people with Disabilities, Home of Treasure in Kwai Chung, was exposed for: tying a severely autistic adult male resident to a bed with his hands bound; restricting residents’ toilet use by tying them to toilets; and providing poor-quality meals, often just rice with vegetables and siu mai dumplings. This tragedy was adapted into the film In Broad Daylight (2023). [113]

First Live News Programme with Sign Language Interpretation

In April, Hong Kong aired its first live current affairs programme with sign language interpretation, This Morning. Due to scheduling issues, the programme was notified to go off air after broadcasting its final episode on October 22, 2021. Following this, Deaf people are only 4.17% likely, compared to hearing people, to receive current affairs information through public broadcasting media. [114]

Recognition of Sign Language Interpreters Increased

By July, the Social Welfare Department formally confirmed the qualifications of 51 sign language interpreters. From 1997 to mid-2016, there had only been 10 certified interpreters in Hong Kong. With over 150,000 Deaf and hard-of-hearing people, the interpreter-to-Deaf ratio was 1:3,000. [115]

Deaf Man Wrongfully Admitted to Psychiatric Hospital

In November, a Deaf man, Mr Liu, had an argument with his family. His mother mistakenly reported him as “mentally ill”. Police officers, unable to communicate in sign language, did not seek an interpreter and relied solely on the mother’s account. Liu was forcibly taken to Tuen Mun Hospital’s emergency room. Due to a lack of sign language interpretation at the hospital, he was wrongfully committed to Castle Peak [psychiatric] Hospital for seven days. His employer mistook his absence for job abandonment and fired him. [116]

2017

Motion to Recognise Hong Kong Sign Language as an Official Language Rejected

A proposal to recognise Hong Kong Sign Language as an official language was debated in the Legislative Council. Some lawmakers opposed it, claiming Hong Kong lacked a standardised sign language system. The motion was ultimately rejected. [117]

Hong Kong Deaf Museum Opened

The Hong Kong Deaf Museum was established online to preserve and document the history of the Deaf community in Hong Kong. [118]

2018

Mass Protest Against Closure of Shine Skills Centre (Kwun Tong)

On November 18, more than 800 people protested against the closure of Shine Skills Centre in Kwun Tong, the only vocational training centre in Hong Kong providing skills assessments for people with special educational needs (SEN). Protesters formed a human chain around the campus, symbolising their determination to protect the school. Banners displayed slogans such as “Support Shine! Oppose Closure!” and “Shine Nurtures Talent, Closure is Cruel”. [119]

2019

Lack of Sign Language Interpretation During Anti-Extradition Bill Protests

By July, the anti-extradition protests had been ongoing for over two weeks, with the government holding multiple press conferences. However, none of these provided sign language interpretation, making it difficult for Deaf people to access critical information. A survey showed that 48% of Deaf people did not know that the extradition bill had been suspended due to lack of accessible news coverage. [120]

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

Art Facilitation and Hospital Archives Subcommittee, Brief History of Psychiatric Service in Hong Kong, the Institute of Mental Health, Castle Peak Hospital https://www3.ha.org.hk/cph/imh/images/aboutUs/subcommittee/Booklet_Traditional.pdf (accessed 1 Feb 2025)

2.

Ibid.

3.

李兆華、潘佩璆、潘裕輝編輯,《戰後香港精神科口述史》,香港:三聯書店,2017,25頁。

4.

Art Facilitation and Hospital Archives Subcommittee, Brief History of Psychiatric Service in Hong Kong, the Institute of Mental Health, Castle Peak Hospital https://www3.ha.org.hk/cph/imh/images/aboutUs/subcommittee/Booklet_Traditional.pdf (accessed 1 Feb 2025)

5.

Ibid., 596.

6.

香港失明人協進會編著,《亡目無礙》,香港:圓桌精英,2015,51頁。

7.

https://www.ebenezer.org.hk/tc/1897-1911 (accessed 2 Feb 2025)

8.

https://www.ebenezer.org.hk/en/1912-1953 (accessed 2 Feb 2025)

9.

李兆華、潘佩璆、潘裕輝編輯,《戰後香港精神科口述史》,香港:三聯書店,2017,26-27頁。

10.

陳意軒著/訪談員,路駿怡、沈栢基訪談,《我的聾人朋友》,香港:圓桌精英,2013,77頁。

11.

Felix Sze, Connie Lo, Lisa Lo, Kenny Chu, Historical development of Hong Kong Sign Language, Sign Language Studies, Volume 13, Number 2, Winter 2013, pp. 155-185 (Article), Gallaudet University Press.

12.

陳意軒著/訪談員,路駿怡、沈栢基訪談,《我的聾人朋友》,香港:圓桌精英,2013,77頁。

13.

https://www.mhahk.org.hk/index.php/journal2024w (accessed 10 Jan 2025)

14.

https://www.hksb.org.hk/en/aboutUs/35272/%E7%99%BC%E5%B1%95%E6%AD%B7%E7%A8%8B/ (accessed 11 Jan 2025)

15.

https://www.nlpra.org.hk/en/about/founder (accessed 11 Jan 2025)

16.

https://www.rehabsociety.org.hk/about-us/hksr-introduction (accessed 18 Dec 2024)

17.

https://www3.ha.org.hk/cph/imh/images/aboutUs/subcommittee/Booklet_Traditional.pdf (accessed 20 Dec 2024)

18.

https://www.rehabsociety.org.hk/about-us/hksr-introduction (accessed 18 Dec 2024)

19.

https://www.sahk1963.org.hk/en_content.php?id=16 (accessed 18 Dec 2024)

20.

https://www.hksb.org.hk/en/aboutUs/35272/Milestones (accessed 10 Dec 2024)

21.

https://www.hksb.org.hk/en/product/18322/%E7%9B%B2%E4%BA%BA%E5%B7%A5%E5%8E%82%E4%BA%A7%E5%93%81 (accessed 10 Dec 2024)

22.

香港失明人協進會編著,《亡目無礙》,香港:圓桌精英,2015,89頁。

23.

https://www.deaf.org.hk/ch/milestone.php (accessed 1 Feb 2025)

24.

https://www.nlpra.org.hk/en/our_services/vocational%20rehabilitation%20services (accessed 21 Feb 2025)

25.

Ibid.

26.

https://www.hkfhy.org.hk/en/about/main/1 (accessed 18 Dec 2024)

27.

香港失明人協進會編著,《亡目無礙》,香港:圓桌精英,2015,90頁。

28.

https://hkphab.org.hk/en-gb/about-us-en/development-history-en (accessed 10 Feb 2025)

29.

Tsui, Kai-ming, Education and Empowerment : a Case Study of Blind Social Activists in Hong Kong, (Master of Philosopy Thesis, Chinese University of Hong Kong). Retrieved from CUHK electronic theses & dissertations collection.

30.

陳意軒著/訪談員,路駿怡、沈栢基訪談,《我的聾人朋友》,香港:圓桌精英,2013,92頁。

31.

https://www.hksb.org.hk/tc/aboutUs/35272/%E7%99%BC%E5%B1%95%E6%AD%B7%E7%A8%8B (accessed 10 Feb 2025)

32.

香港失明人協進會編著,《亡目無礙》,香港:圓桌精英,2015,121-122頁。

33.

香港失明人協進會編著,《亡目無礙》,香港:圓桌精英,2015,145頁。

34.

香港聾人協進會,《香港聾人歷史(第一冊)》,2011,2頁。

35.

https://www.deaf.org.hk/ch/milestone.php (accessed 10 Feb 2025)

36.

https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr06-07/english/panels/ws/papers/ws0709cb2-2348-1-e.pdf (accessed 11 Feb 2025)

37.

https://www.eduhk.hk/cird/publications/edpolicy/03.pdf (accessed 7 Jan 2025)

38.

香港失明人協進會編著,《亡目無礙》,香港:圓桌精英,2015,145頁。

39.

香港聾人協進會,《香港聾人歷史(第一冊)》,2011,30頁。

40.

https://www.rehabsociety.org.hk/transport/rehabus/history (accessed 8 Jan 2025)

42.

香港失明人協進會編著,《亡目無礙》,香港:圓桌精英,2015,126頁。

43.

https://www.ha.org.hk/visitor/ha_visitor_text_index.asp?Content_ID=100162&Lang=ENG&Dimension=100&Parent_ID=10179&Ver=TEXT (accessed 21 Dec 2024)

44.

https://www.ha.org.hk/visitor/ha_visitor_text_index.asp?Content_ID=100162&Lang=ENG&Dimension=100&Parent_ID=10179&Ver=TEXT (accessed 21 Dec 2024)

45.

李兆華、潘佩璆、潘裕輝編輯,《戰後香港精神科口述史》,香港:三聯書店,2017,215頁。

46.

https://www.nlpra.org.hk/tc/our_services/hh/25 (accessed 11 Feb 2025)

47.

https://www.4limb.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2009-2010%E5%B9%B4%E5%A0%B1.pdf (accessed 20 Jan 2025)

48.

https://www.hkjcpmh.org.hk/zh-hant/history (accessed 20 Jan 2025)

49.

李兆華、潘佩璆、潘裕輝編輯,《戰後香港精神科口述史》,香港:三聯書店,2017,43頁。

50.

https://www.parentsassn.org.hk/about (accessed 14 Jan 2025)

51.

https://www.hkdanceyearbook.org/main/dance/eng/group_details.php?id=1-30# (accessed 14 Jan 2025)

52.

香港失明人協進會編著,《亡目無礙》,香港:圓桌精英,2015,128頁。

53.

https://www.hkjcpmh.org.hk/zh-hant/rule (accessed 13 Jan 2025)

54.

香港失明人協進會編著,《亡目無礙》,香港:圓桌精英,2015,132頁。

55.

https://www.mhahk.org.hk/index.php/about/milestone (accessed 20 Dec 2024)

56.

https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/199910/16/1016109.htm (accessed 13 Jan 2025)

57.

https://www.hkjcpmh.org.hk/zh-hant/history (accessed 21 Dec 2024)

58.

Ibid.

59.

Ibid.

60.

https://www.hkjcpmh.org.hk/zh-hant/estate (accessed 21 Dec 2024)

61.

https://thearcmov.org/history-of-people-first (accessed 21 Dec 2024)

62.

http://www.chosenpower.org/aboutus/history/%e5%8d%93%e6%96%b0%e7%99%bc%e5%b1%95%e5%8f%b2-1995-1999 (accessed 21 Dec 2024)

63.

https://www.hk01.com/article/226024?utm_source=01articlecopy&utm_medium=referral (accessed 15 Dec 2024)

64.

https://www.hkjcpmh.org.hk/zh-hant/courtcase1993%20 (accessed 21 Dec 2024)

65.

http://www.cslds.org/v4/about.php (accessed 8 Dec 2024)

66.

http://www.cslds.org/v4/about.php (accessed 8 Dec 2024)

67.

https://www.4limb.org/%E7%B0%A1%E4%BB%8B (accessed 13 Dec 2024)

68.

https://www.careheart.org.hk/?page_id=20 (accessed 11 Dec 2024)

69.

https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/200210/22/1022121.htm (accessed 7 Dec 2024)

70.

https://www.amss1996.org.hk/aboutus (accessed 10 Dec 2024)

71.

https://tinyurl.com/tvbnewsaboutdisabilitylaw (accessed 6 Jan 2025)

72.

香港失明人協進會編著,《亡目無礙》,香港:圓桌精英,2015,149頁。

73.

https://concordorghk.wordpress.com/about (accessed 7 Jan 2025)

74.

https://www.ctvihongkong.org (accessed 7 Jan 2025)

75.

https://hknmda.org.hk (accessed 6 Jan 2025)

76.

http://hkbdeafc.weebly.com/about-hkbdc-38364260443204338598.html (accessed 11 Dec 2024)

77.

https://tinyurl.com/whitecardintro (accessed 11 Jan 2025)

78.

https://www.facebook.com/awdhk/?locale=zh_HK (accessed 8 Jan 2025)

79.

http://www.tos.org.hk (accessed 6 Dec 2024)

80.

https://www.hkdanceyearbook.org/main/dance/eng/group_details.php?id=1-25 (accessed 2 Dec 2024)

81.

Carol A. G. Jones, Lost in China? Law, Culture and Identity in Post-1997 Hong Kong, Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 May 2015, pp. 114 – 140.

82.

https://www.hksccm.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=532 (accessed 8 Dec 2024)

83.

http://www.cslds.org/v4/about.php (accessed 8 Dec 2024)

84.

https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr05-06/chinese/hc/sub_com/hs01/papers/hs010227cb1-990-1-c.pdf (accessed 9 Dec 2024)

85.

https://www.deaf.org.hk/documents/news/RP/news_8_7_2005_2.htm (accessed 11 Nov 2024)

86.

https://www.hk01.com/article/278812?utm_source=01articlecopy&utm_medium=referral (accessed 10 Nov 2024)

87.

https://ubeat.com.cuhk.edu.hk/166_手語傳譯缺聾人求醫苦不堪言 (accessed 11 Nov 2024)

88.

香港聾人協進會,《香港聾人歷史(第一冊)》,2011,11頁。

89.

https://www.lwb.gov.hk/en/highlights/UNCRPD/index.html (accessed 12 Dec 2024)

90.

https://www.silence.org.hk/en/background (accessed 10 Dec 2024)

91.

https://youtu.be/HPFQpEq22no?si=XXLZ5Sz4p9FUvyKo (accessed 11 Jan 2025)

92.

http://orientaldaily.on.cc/cnt/news/20091102/00176_006.html (accessed 9 Jan 2025)

93.

https://www.hkdanceyearbook.org/main/dance/eng/group_details.php?id=1-3 (22 Dec 2024)

94.

https://www.hksb.org.hk/en/newsDetail/8320090 (accessed 4 Jan 2025)

95.

https://shortpress.wordpress.com (accessed 4 Jan 2025)

96.

https://mydeaffriends.wordpress.com/%E5%B0%8F%E5%B8%B8%E8%AD%98/%E5%9C%8B%E9%9A%9B%E8%81%BE%E4%BA%BA%E6%95%99%E8%82%B2%E6%9C%83%E8%AD%B0 (accessed 13 Jan 2025)

97.

https://ubeat.com.cuhk.edu.hk/166_手語傳譯缺聾人求醫苦不堪言 (accessed 13 Jan 2025)

98.

https://hkac.org.hk/en/press_release_detail/?u=jVeHVZzsiFE (accessed 11 Oct 2024)

99.

https://www.inmediahk.net/%E6%88%91%E8%A6%81%E5%9B%9E%E5%AE%B6%EF%BC%8C%E8%B7%AF%E9%9B%A3%E8%A1%8C%EF%BC%81%EF%BC%81%EF%BC%81%E5%85%A8%E7%99%B1%E7%97%85%E4%BA%BA%E7%97%85%E5%BA%8A%E9%81%8A%E8%A1%8C (accessed 20 Jan 2025)

100.

https://shortpressaction.wordpress.com (accessed 11 Jan 2025)

101.

https://evchk.fandom.com/zh/wiki/%E9%A6%99%E6%B8%AF%E5%82%B7%E5%81%A5%E5%85%B1%E8%99%95%E8%A8%8E%E8%AB%96 (accessed 11 Jan 2025)

102.

真鐸事件監察聯盟 https://www.facebook.com/groups/490822594306939 真鐸學生權益關注組https://www.facebook.com/concernchuntok 聾人站出來!不再啞忍!https://www.facebook.com/deafpeople.standup (accessed 11 Jan 2025)

103.

https://www.tidhk.com (accessed 10 Jan 2025)

104.

105.

https://www.hk01.com/article/226012?utm_source=01articlecopy&utm_medium=referral (accessed 8 Jan 2025)

106.

https://tinyurl.com/deafprotest2014 (accessed 11 Jan 2025)

107.

https://tinyurl.com/signlanguage2014 (accessed 7 Jan 2025)

108.

https://chomecaresa.home.blog/%e5%9c%98%e9%ab%94%e7%b0%a1%e4%bb%8b (accessed 20 Jan 2025)

109.

https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr12-13/chinese/hc/sub_com/hs51/papers/hs510224cb2-891-5-c.pdf (accessed 20 Jan 2025)

110.

https://news.mingpao.com/ins/%E6%B8%AF%E8%81%9E/article/20231116/s00001/1700040083263 (accessed 16 Jan 2025)

111.

http://audeahk.org.hk/index/en/home (accessed 11 Jan 2025)

112.

http://www.hongkiu.org/issue.htm (accessed 11 Jan 2025)

113.

https://www.hk01.com/article/309348?utm_source=01articlecopy&utm_medium=referral (accessed 11 Jan 2025)

114.

115.

https://www.mpweekly.com/culture/cu0001/%E6%89%8B%E8%AA%9E-%E8%81%BE%E4%BA%BA-%E6%AE%98%E9%9A%9C%E4%BA%BA%E5%A3%AB-22434 (accessed 13 Feb 2025)

116.

https://www.inmediahk.net/node/1047422 (accessed 14 Feb 2025)

117.

https://sites.google.com/view/hksladvocates-official-recog/home (accessed 17 Jan 2025)

118.

www.facebook.com/deafmuseum2017 (accessed 15 Jan 2025)

119.

https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/society/article/2173813/opposition-relocation-job-training-centre-disabled-teenagers (accessed 13 Dec 2024)

120.

https://www.inmediahk.net/node/1065752 (accessed 15 Jan 2025)

has a background in literature and cultural studies, and she has been engaged in inclusive and community arts work in Hong Kong for over ten years. She has been involved in curating, self-publishing, performance art creation, and research. Currently, she is striving to become a researcher in Disability justice, restarting her learning in Hong Kong Sign Language, and is soon to become a mother.