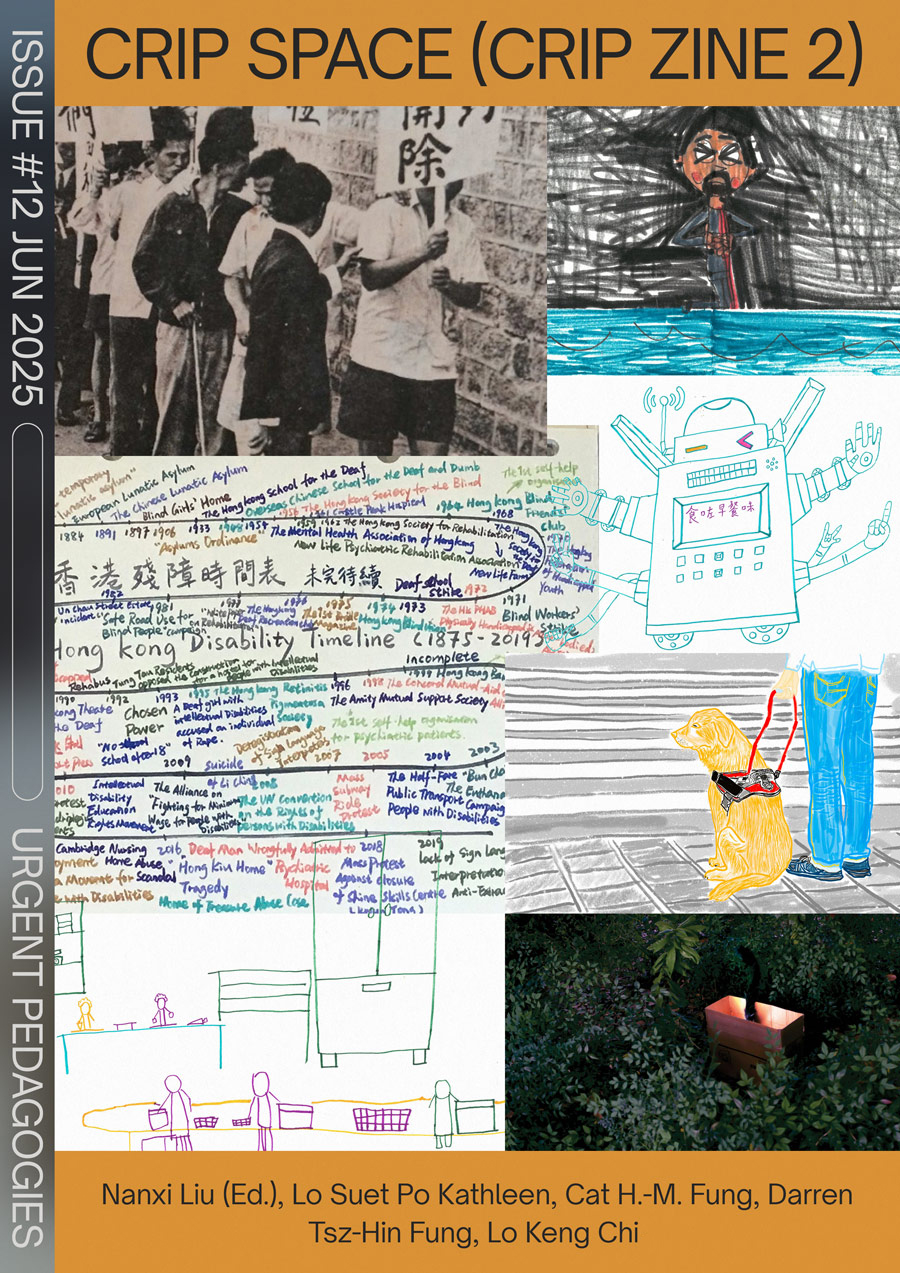

Might as Well Leave It to Medication?

Lo Suet Po Kathleen

CATEGORY

Lo Suet Po Kathleen calls for a reevaluation of how society perceives and treats mental health, urging a focus on therapy, community support, and the recognition of the deep-rooted social issues that contribute to mental health struggles.

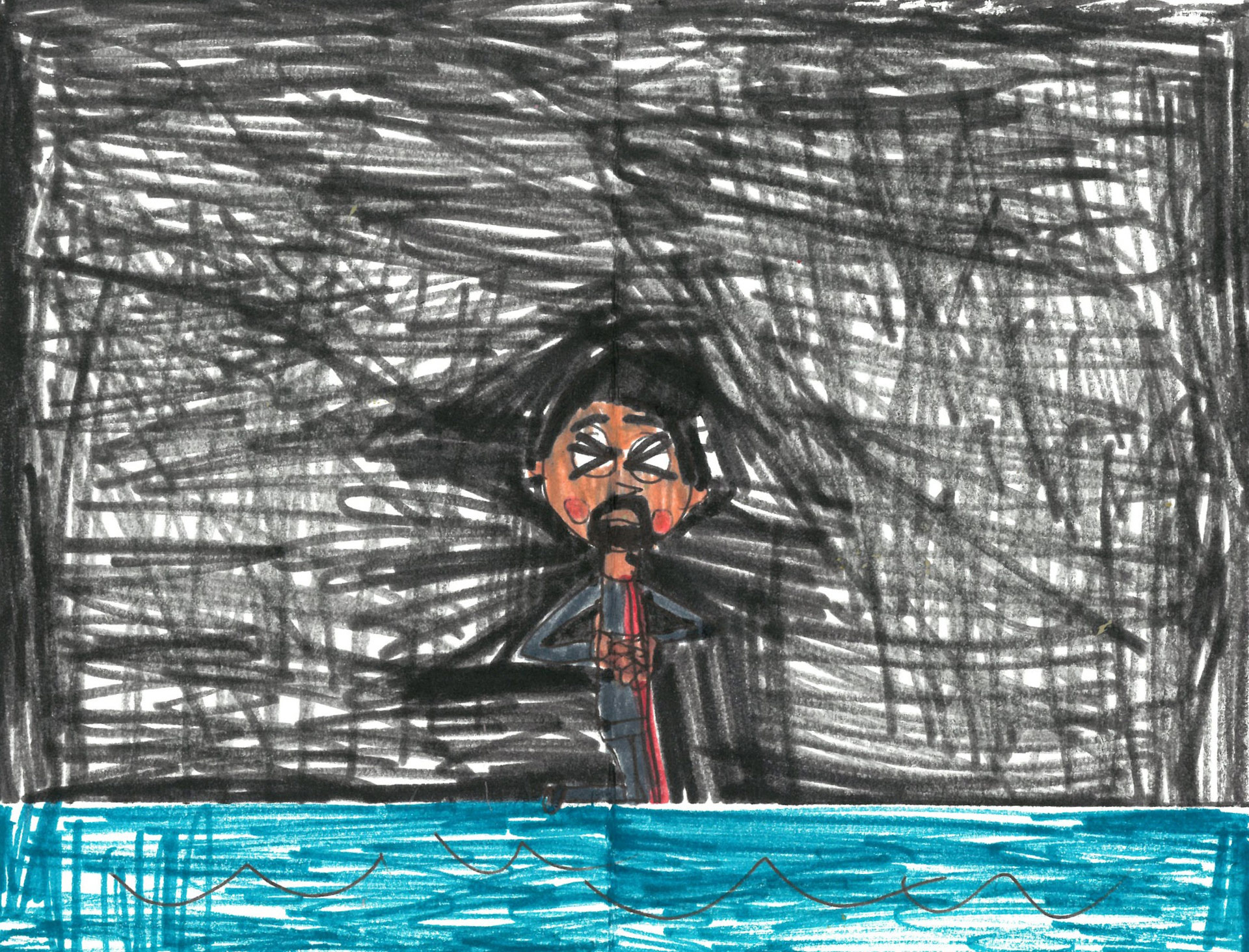

Marginalised communities are often considered outside the normative system and are difficult to understand. In 2023, I decided to enter the local transgender community with my camera, as a heteronormative Disabled artist, to learn from their culture and knowledge, and explore the label “marginalised”.

I established connections with the Hong Kong transgender community and explored identity, intersectionality and the diversity of humanity. I did this over a two-year period, by taking portrait photos and opening many dialogues: on gender constructs; the simultaneous existence of dominance and subordination; unique struggles that constitute marginalised identities; and specifically on the nature of portrait-making in modern times.

In my personal Disability experience, I have been diagnosed with psychosis and this pathological label has, for years, led me to feel lost in the medical system.

At the end of the day, how does a person become “marginalised” in society?

In 2017, I experienced a month-long episode of anxiety and panic. Just as the month was about to end, I managed to reset myself. It was the first time I had ever gone through something like that, and for peace of mind, I decided to seek medical advice. Even though I told the doctor that I felt fully recovered, they still diagnosed me with schizophrenia — a label that has now permanently been attached to my medical records.

To “prevent relapse”, the doctor prescribed psychiatric medication. So, I took it and kept taking it. Four years later, the doctor told me that I couldn’t stop. They explained that without the medication, I would have an 80% high chance of relapsing.

For four years, I had no symptoms at all, for example, hallucinations or uncontrollable thoughts, yet I was constantly battling the severe side effects that disrupted my work and daily life.

Why was I taking medication for a condition I no longer had, knowing that the side effects were doing more harm to my body?

Am I supposed to stay on them for a lifetime?

I started discussing tapering off the medication with my medical team. But under immense pressure from my family, social workers, and doctors, I struggled with self-doubt.

I ultimately refused to go through “hospitalisation for medication trials”. I refused to go through months of testing all the psychiatric drugs you could name on my body, to find one with the “least side effects”.

This experience made me realise the medicalisation of daily life and the importance of body autonomy.

I’ve been off medication for years, with approval from the doctors, and feel much more refreshed and energetic. Yet every time I mentioned it, there would be slight panic: “Not taking meds is dangerous!”

A year ago, I accepted a media interview. The final published version heavily emphasised the benefits and necessity of taking medication, leaving out much of my perspective. So, I stopped bringing it up.

Let’s be real: every Hong Konger has stress and emotional struggles.

“Nine out of ten Hong Kongers have mental illness; the tenth is just undiagnosed.”

Mental health risks are deeply embedded in daily life, affecting everyone — so why is my choice of stopping medication such a big deal?

I once had a brain scan that showed that I naturally produce high dopamine levels making me more hypersensitive. But before anyone jumps to conclusions — let’s not over-medicalise it.

The term “highly sensitive person” (HSP) is a more relatable and widely accepted way to describe my condition.

In today’s world, with constant digital stimulation, most people are becoming more sensitive. Maybe we should all get brain scans.

I won’t deny that I do have mental health challenges. “Referencing” (association of unrelated matters) is a psychosis symptom often used to explain patients’ hypersensitive mental experiences. In my view, these experiences are spiritual or religious — but they’re not hallucinations nor signs of insanity.

If you haven’t experienced it, you wouldn’t understand the difference.

My spiritual experiences aren’t visual or auditory hallucinations. They merely involve sensing the energy of the universe, the chemistry between all things on the level of collective unconsciousness. Through my body, I can perceive higher dimensions of existence.

The term “synchronicity” would be much more concise and precise:

“It refers to meaningful coincidences or events that appear to be related but lack a causal connection, often interpreted as a sign of deeper significance or alignment. The concept is widely associated with the Swiss psychologist Carl Jung.” (from Wikipedia)

Simply put: the universe is vast. Humans are not the only form of life.

Highly sensitive people are simply more attuned to higher-dimensional interactions — meaning they could be easily overwhelmed by sensory feelings.

I won’t deny that life experiences have shaped my flaws as a human being, creating difficulties and stress in everyday life. Especially when society tends to define people by their weaknesses, adding even more pressure.

These factors make me mentally vulnerable, but taking medication will not improve my mental health. Repeat this, until you fall asleep.

Highly sensitive people overanalyse everything. We notice small details that others miss — details that connect to larger issues 99% of the time.

This ability helps solve problems, yet people dismiss it as “anxiety”.

I don’t feel anxious from rational problem-solving. But hostility and negative emotions from others do make me uneasy.

Mental illness exists on a spectrum — it’s not just a rigid medical definition of pathological pureness.

In a Clubhouse discussion (an audio-based social networking service), I once asked a young psychiatrist:

“If OCD [obsessive-compulsive disorder] treatment aims to regulate dopamine for ‘fear extinction’, wouldn’t therapy be more important than just prescribing antidepressants?”

Most psychiatric meds function like anaesthetics — they numb highly sensitive people to make them less sensitive. But what is the downside? Addiction, severe side effects, and long-term damage.

Even after years of taking meds, people often fall back to their initial state once they stop. Meds exacerbate family issues, disrupt social life, and affect work performance — patients end up fighting side effects every single day.

Now, sure, there’s a new drug this year with “the least side effects ever”. So, is there still a reason not to take them? Instead of taking meds with passion and loyalty, why not plant trees and do good deeds?

Mental illness does not originate from a lack of medication at birth. It stems from deep-rooted societal issues. For example, social media is addictive by design. One viral post can trigger mass anxiety. Should we rely on social workers to fix that?

Why doesn’t psychiatric treatment focus on therapy, counselling and community support, instead of just pushing meds? The more unresolved the social issues are, the more mental health diagnoses we will see. Yet society’s main concern is whether we’re taking our meds or not.

Hospitals force patients into long-term sedation instead of addressing trauma and root causes. Shouldn’t re-training the brain and body be the real solution?

Society still clings to the belief that “if you’re sick, see a doctor”. But do medical diagnoses actually stigmatise patients instead of helping them?

A clinical psychologist responded in the Clubhouse session:

“Unfortunately, I don’t know why. The healthcare system is overloaded. Quick solutions mean meds are the first-line treatment. Resources aren’t focused on psychotherapy.”

- Patients can request a referral to a psychologist at the public hospital — but the queue takes years.

- Subsidised counselling exists — only for permanently low-income residents.

- Private therapy is available — only for the permanently wealthy.

Recently, some organisations have started offering free counselling services — sometimes up to ten sessions. For three years, I had therapy sessions where someone simply listened to me. Counselling is a temporary release — a moment to put down the burden. But once you step out, do the problems actually get solved?

Family trauma, education pressures, social dynamics, workplace survival — an endless list of struggles. In the end, people just say:

“It’s a personal issue. You couldn’t handle society’s demands.”

So, to “fix” personal issues — we might as well leave them to medication, right?

Photography by Lo Suet Po Kathleen, image courtesy of the author

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

is a self-baked photographer since 2020, she has been exploring arts and photography with a focus on understanding marginalised communities. Her artworks include photography, poetry, writing, experimental music and video. Kathleen initiated the art project “Variety of Beings”, conducted interviews and portrait photos for 20 transgender people in Hong Kong. Her works were showcased in her solo exhibition and a photobook, which was shortlisted in Cross All Borders 2024: Hong Kong Competition Showcasing New Visual Artist with Disabilities.