Learnings/Unlearnings: Resources, Frameworks and Concepts for Playful Built Environment Learning

Anna Keune, Marta Brkovic Dodig, Angela Million, Rosie Parnell, Claudia Carter, Simeon Shtebunaev, Hannah Klug, John Wood, Claudia Carter, Emma Jones

CATEGORY

Welcome to Learnings/Unlearnings Reader #2: Resources, Frameworks and Concepts for Playful Built Environment Learning, guest edited by Anette Göthlund and Meike Schalk. The Reader includes contributions from the section “Conversing: Environmental Learning Discourses” from the conference Learnings/Unlearnings: Environmental Pedagogies, Play, Policies, and Spatial Design, which took place in Stockholm in September 2024.

The contributions in Reader #2 focus on the multifaceted realm of theory and discourses that shape and broaden our understanding of environmental learning, as well as how they have shaped hands-on formats, methodologies, and “concept-tools” for action (Frichot 2016).

A recurrent topic in contemporary educational, cultural, and societal discourses concern the need for different literacies. The following contributions see spatial literacy and climate literacy as part of an education in sustainability and the environment. Originally used in relation to reading, writing, and the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, exchange, and use communicative tools, the concept has since expanded to encompass visual literacy, media literacy, AI literacy, and even civic literacy, among others. The importance of bringing this concept to discussions about environmental pedagogies becomes clear with UNESCO’s definition, which connects literacy to democratic values: “Literacy involves a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and wider society” (UNESCO 2017). Literacies entail a combination of multiple ways of communicating and making meaning, including such modes as visual, audio, spatial, behavioral, and gestural (New London Group, 1996).

In her contribution, Anna Keune gives three recommendations for the design of learning spaces. She notes that despite the charge to serve all people, fields within the built environment struggle with gender- and race-related discrimination and inequalities. Therefore, broadening participation and promoting parity among diverse groups of people within the built environment is an important concern that, as she argues, needs to be addressed when designing learning environments that recognize a wide range of cultural practices and acknowledge a variety of people as legitimate contributors. In the three recommendations for the design of learning environments that have implications for the design and implementation of curricula and pedagogical practices in built environment education, Anna discusses ways to achieve equities in built environments fields, including strategies such as “designing for material diversity,“ “designing for recognition” and “designing for empathy.” Anna shows how these recommendations can enhance participation in the built environments sector.

In the contribution by Marta Brkovic Dodig, Angela Million, and Rosie Parnell, Built Environment Education (BEE) is characterized as an evolving but still fragmented field. The authors identify a need to establish a shared framework, fostering collaboration, and advancing BEE as a recognized educational discipline. Through interviews with BEE practitioners within various institutional settings, internal workshops, as well as document analysis and a literature review, BEE situates itself within a broader educational framework. An important contribution and achievement in establishing the field was the mapping of the pedagogical underpinnings, including its concepts and methodologies, presenting BEE as “Pedagogies of Space.” A forthcoming handbook—Built Environment Education for Children and Youth: Establishing the Field—captures and synthesizes the findings of the study, seeking to learn from, and to bring together, the ever-growing global BEE community.

How can children and young people, who are at the center of our efforts and activities when working in the field of environmental learning, be included, regardless of our diverse roles as educators, architects, artists, or urban planners? Today many young people express fears and concerns about climate change and its effects. How can we inspire them to mobilize climate action? Claudia Carter and Simeon Shtebunaev collaborated with thirteen teenagers in Birmingham, aged 14–18, with the aim of engaging young people in climate literacy and action guided by the notion of “think global, act local.” Inspired by an action-research approach, they applied a STEAM and Design-Thinking infused co-design method, working with young people to explore climate change realities at a local scale. The key output was the playable board game “CLIMANIA: The Climate Action Game,” which focused on adaptations within an urban sustainability context. The game has since been used as a tool for education in formal and informal settings, for engagement, advocacy, discussion, action-informing, and as a professional development tool.

Hannah Klug puts forward a “Pedagogy of Resonance” as a spatial framework to explore informal urban settlements in Lima as learning spaces that form between communities and their environments. She discusses “resonances” through the work of the Peruvian student collective IntuyLab, that initiated a long-term participatory design project to build a community center in the Alto Perú neighborhood, of which she was part of. Hannah’s contribution recognizes the geographical situatedness of discourses that engage with the exploration of theoretical perspectives and debates in the understanding of environmental learning from diverse cultural standpoints. In a crises-ridden world, she argues that architecture offers the potential to foster critical and inclusive spatial practices for future generations. Her contribution shows how working in collaboration with informal neighborhoods can transform architecture education.

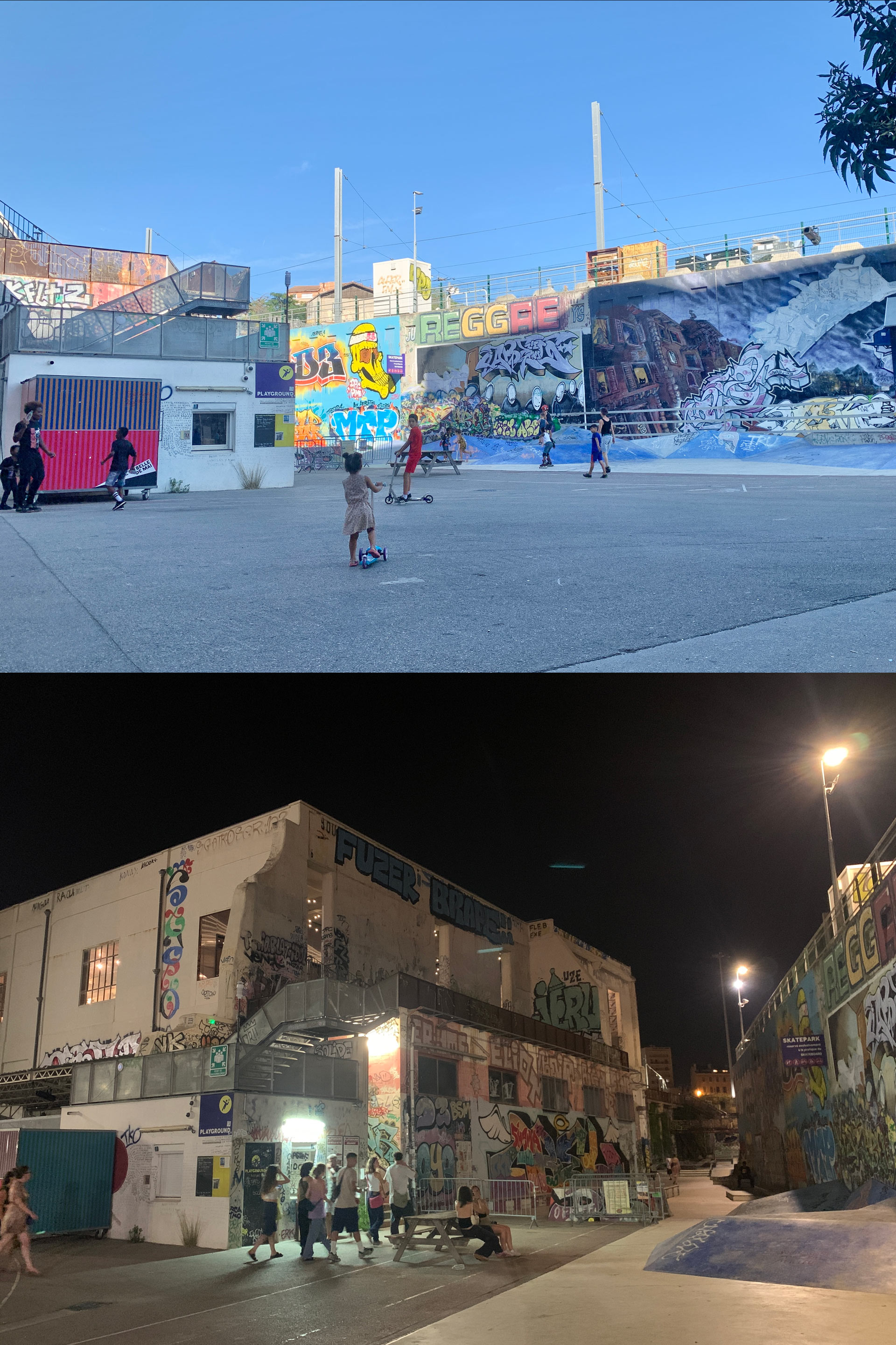

John Wood offers “Fields of Play” as an urban concept and “instrument” for environmental designers, enabling identification, the acquisition of social skills, and sensitivities for diverse societies. Fields of Play are hereby characterized as ephemeral, fluid, spatio-temporal, and ambiguous spaces that invite play. Through the case study “La Friche” in Marseille, John discusses the example of the public square, Platforme, designed by ARM Architecture, as a possible space of encounter with curated and unprogrammed spaces and elements, where children can play by day, while adults can listen to music at night. Conceptually, “Fields of Play” depart from the thinking of social spaces as fixed categories, or for prescribed uses and users, but rather as spaces capable of provoking chance encounters across different generations and diverse social groups, encouraging relationships within and across them.

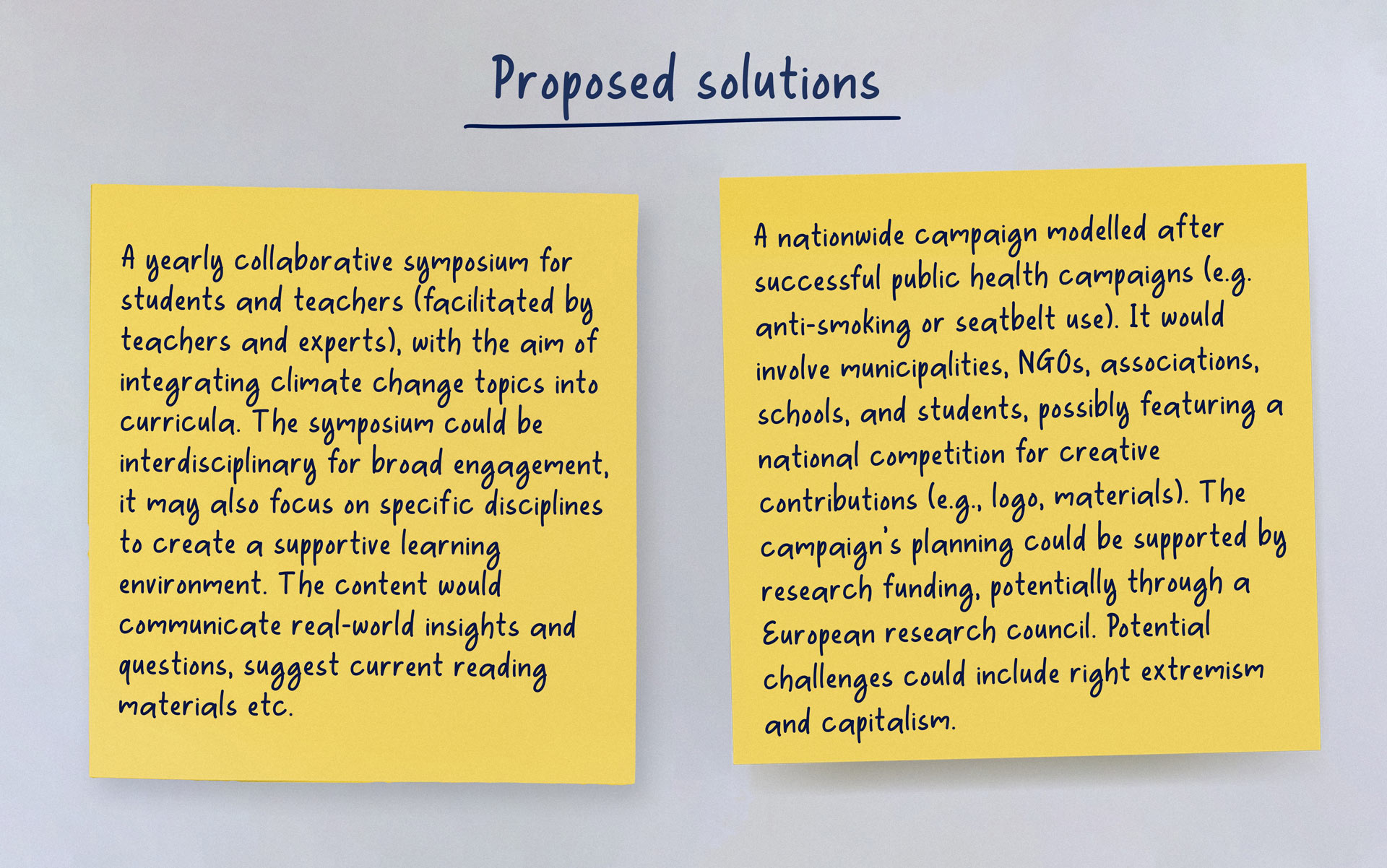

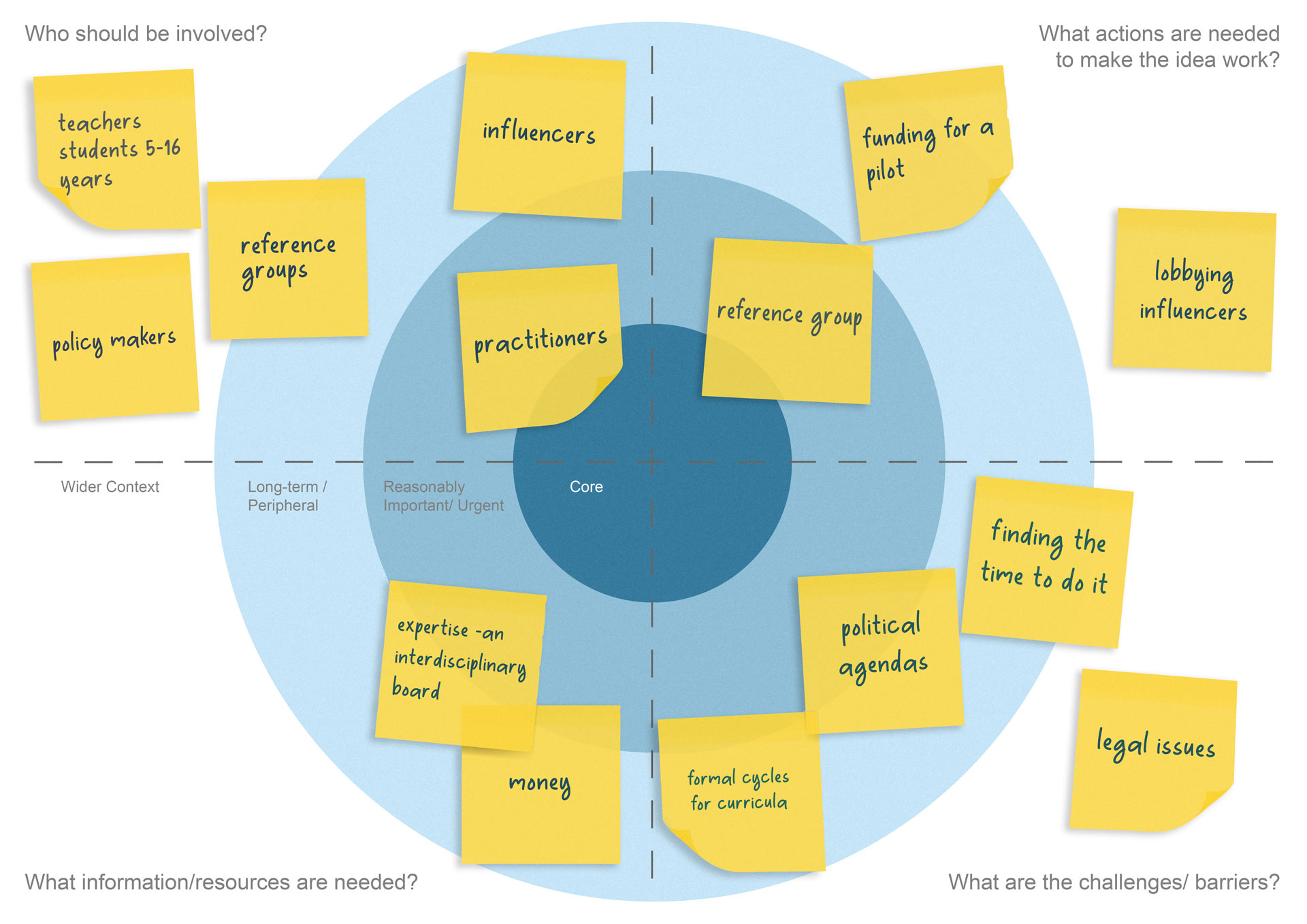

At the Learnings/Unlearnings conference Claudia Carter and Emma Jones invited the participants to join a workshop to explore how the use of STEAM methods can facilitate discussions and ideations among staff and students in environmental and sustainability education (the authors took part in the workshop!). Carter and Jones argue that adding the A (for Arts) to STEM (Sciences, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) opens for transdisciplinary pedagogies and new ways for students and teachers to become more applied, multi-skilled, and holistic in their inquiry and creations. Taking the participants’ own knowledge and understanding as a starting point, the workshop enabled us to experience a STEAM approach in practice. The workshop included a warming-up and a mind mapping exercise that created a platform for self-reflection, sharing experiences, and the development of ideas for advancing environmental and climate literacy in our local educational settings.

References

Frichot, Hélène. 2016. How to Make Yourself a Feminist Design Power Tool. Baunach, Germany: AADR (Spurbuchverlag).

The New London Group. 1996. “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures”. Harvard Educational Review, Vol 66, Nr. 1.

UNESCO. (2017). “Literacy.” UNESCO Institute for Statistics. http://on.unesco.org/literacy-map

Contents

Designing for Broadening Participation in Built Environments Education: Insights from Learning Sciences Research

Anna Keune

Youth selecting tangible materials for generating AI-based arts. Photo: Anna Keune

The built environment fields, including architecture, urban planning, and construction, substantially contribute to how people live and learn together. These fields innovate settings that can address human needs and inspire new arrangements and activities among groups of people. Despite the charge of the built environment fields to serve everyone, the built environment fields face inequities. For instance, key actors in the built environments fields that monitor equitable participation and access to the field identified that race and gender-related discrimination has been increasing. Such inequities have a detrimental impact on people’s lives because not all groups of people are participating in and contributing to the design of the built world. Certain needs and activities are at risk of being overlooked or even dismissed. Thus, broadening participation and facilitating parity across groups of people in the build environments fields is an important charge. This charge has foundational roots in the design of learning environments that acknowledge a wide range of cultural practices, that recognize a diverse range of people as legitimate contributors, and that build strength from a place of empathy.

In this contribution, I develop three recommendations for designing learning environments that have implications for the design and implementation of curricular and pedagogical practice in built environments education. The principles are based on three research studies that are grounded in learning sciences scholarship. The learning sciences focus on understanding how people learn by studying authentic learning experiences (e.g., Kolodner, 2004). This includes creating theories about learning, emphasizing the processes involved in learning, and applying these learning theories to create new learning environments. Following this, learning scientists study whether and how learning takes place within such novel environments by using methods that are aligned with learning theories and new designs. The studies in this paper are based on constructionist and socio-material approaches to learning (e.g., Papert, 1980). Constructionist approaches to learning amuse people internalize complex ideas through the manipulation of tools and materials in the design of personally meaningful projects (e.g., Fenwick et al., 2010). An underlying contribution of socio-material approaches is that introducing novel materials can generate transformative disruptions because it invites new ways of doing domain-relevant learning.

The three recommendations shared here are intended to support the design of learning environments to broaden participation. The first recommendation emphasizes the importance of incorporating a diverse range of materials that connect to underrepresented practices. The second recommendation suggests to design for recognition, which involves prominently displaying student work to make connections within the field visible. The third recommendation highlights designing for empathy, collating for opportunities that utilize familiar techniques to encourage critical engagement with less familiar ones. I will illustrate these recommendations by drawing on three qualitative empirical research studies.

Designing for material diversity

Designing for diversity involves incorporating less common materials socio-historically linked to underrepresented groups within a field. To illustrate this design recommendation, I draw on research that examined traditional fiber crafts as a context for computational learning (Keune, 2022; Keune, 2024). By exploring textile production as computational, the research highlights its potential to expand computing cultures, which has been linked to enhancing persistence among underrepresented groups in fields like computing (Buechley, 2006; Peppler & Glosson, 2014). While the broader study covered several crafts, I focus on fabric manipulation techniques such as smocking, where sewists connect dots on a grid to create three-dimensional fabric forms. I drew on the constructionist theory of learning that suggests that while individuals may gravitate toward one effective method, supporting a range of approaches alongside dominant practices can help broaden computing cultures. Through artifact analysis sessions with computer science experts, I investigated their understanding of algorithmic design in middle school students’ sewn projects.

Computer science experts identified sewing relates to algorithms as a novel material for computing education. The analysis showed that sewing offers three different opportunities for practicing algorithms: (1) a graphic representation of algorithms, which involves drawing matrix patterns to plan projects; (2) a performative approach, in which the act of stitching translated graphical patterns into a reliable routine of stitches; and (3) a syntactic perspective, which emphasizes verbal and written formalization of patterns, exemplified by a pseudocode translation (i.e., a description of the steps used for crafting with computer programming conventions) used to analyze youth projects over time. Overall, this research shows that sewing holds promise as an additional material for teaching computational concepts. By advocating for material diversity, the research highlights opportunities to enhance pedagogies through unconventional materials, promoting a broader range of learning experiences and facilitating comparisons between different ways of knowing.

Designing for recognition

Design for recognition is a recommendation for making and building spaces that aim to influence long-term learning trajectories. This approach advocates for prominently displaying student work to highlight their connection to a field. Overall, the maker movement in K-16 educational settings has attracted people to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields (Barton & Tan, 2018; Buchholz et al., 2014; Pinkard et al., 2017). The design recommendation shared here is grounded in ethnographic research conducted in maker educational settings that have shown potential for engaging underrepresented people in STEM (Keune & Peppler, 2019; Keune et al., 2019; Keune et al., 2021). The study focused on young makers and their projects, particularly a jukebox piano created by a young woman. Utilizing audiovisual data, including project photographs and online posts, the analysis used a multimodal approach to examine the disruptions of materials layered on the piano, its spatial placement within the makerspace, and its representation in online networks.

The young woman transformed an old piano into a jukebox by adding electronics and craft materials, enabling it to play songs from a playlist when its keys were pressed. The design highlighted connections between her project and engineering, illustrating a blend of craft and engineering practices and demonstrating her presence in a field where women are often underrepresented. Over three years, I observed the project’s evolution and increasing visibility in the makerspace. The piano’s relocation enhanced the young woman’s recognition among peers, leading to public acknowledgment of her engineering skills and motivating her to pursue an engineering college major. Designing for recognition is a powerful way to counter inequities by ensuring young people are acknowledged. By making youth projects visible, we can impact life trajectories.

Jukebox piano. Photo: Anna Keune

Designing for empathy

Design for empathy emphasizes the importance of using familiar tools and techniques to encourage critical discussions about unfamiliar technologies, particularly in AI. As AI tools become increasingly prevalent in education, there is a pressing need for young people to understand AI ethics (Holmes et al., 2022; Morales-Navarro, 2023). The study investigates how familiarity with tangible arts-making can serve as a way into AI literacy and engineering (Keune et al., 2024; Letourneau et al., 2021; Peppler et al., 2020). The research involved 12 young women participating in the summer camp at a university setting in Germany, where they engaged in activities that combined personal drawings with AI-generated expansions and integrated tangible materials into their digital outputs. We analyzed the interactions using OECD AI ethics principles (OECD, 2021), such as human growth, sustainable development, and well-being, including how AI enhances creativity as well as transparency and explainability, like making it possible to understand outcomes of AI systems.

The analysis showed that designing for empathy, for instance, by engaging with AI through familiar arts practices, allowed the participants to critique the AI’s creative output and fostered discussions around several AI ethics principles, including creativity and transparency. The participants said that the AI did not adequately support creative expression, and the AI’s outputs were criticized for lacking transparency regarding the decision-making processes, raising concerns about accountability. The research suggests that design for empathy by incorporating familiar artistic practices can facilitate a deep engagement with new digital tools and their ethical implications, creating positive learning experiences and encouraging broader participation in discussions about AI ethics. The study highlights the potential for integrating traditional methods with emergent technologies to enhance understanding among young learners.

The design recommendations hold implications for built environments and curricular and pedagogical practice that seek to counteract inequities. The recommendations can enhance participation in the built environments sector. Incorporating a diversity of materials can equip learners with insights into the relevance of various domains, allowing them to practice transferring skills across different contexts. A student-centred approach in design for recognition emphasizes the significance of effectively sharing and showcasing student work to foster long-term engagement. The work calls to identify long-term spatial opportunities that enable learners to transition from a reluctance to embrace a field to actively pursuing future prospects within the field. Lastly, design for empathy, particularly through integrating familiar elements into educational practices, is essential for preparing students to critically analyze emerging tools and technologies and their implications for addressing human needs within the field.

References

Barton, Angela Calabrese, Edna Tan, and Yasmin B. Kafai. 2018. STEM-Rich Maker Learning: Designing for Equity with Youth of Color. New York London: Teachers College Press.

Buchholz, Beth, Kate Shively, Kylie Peppler, and Karen Wohlwend. 2014. “Hands On, Hands Off: Gendered Access in Crafting and Electronics Practices.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 21 (4): 278–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2014.939762.

Buechley, Leah. 2006. “A Construction Kit for Electronic Textiles.” In 2006 10th IEEE International Symposium on Wearable Computers, 83–90. Montreux, Switzerland: IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISWC.2006.286348.

Holmes, Wayne, Kaska Porayska-Pomsta, Ken Holstein, Emma Sutherland, Toby Baker, Simon Buckingham Shum, Olga C. Santos, et al. 2021. “Ethics of AI in Education: Towards a Community-Wide Framework.” International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education 32 (3): 504–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-021-00239-1.

Keune, Anna. 2022. “Material Syntonicity: Examining Computational Performance and Its Materiality through Weaving and Sewing Crafts.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 31 (4–5): 477–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2022.2100704.

Keune, Anna. 2024. “Learning within Fiber-Crafted Algorithms: Posthumanist Perspectives for Capturing Human-Material Collaboration.” International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning 19 (1): 37–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-023-09412-1.

Keune, Anna, Santiago Hurtado, and Živa Simšič. 2024. “Exploring AI Ethics through Educational Scenarios with AI Generative Arts Apps.” In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference of the Learning Sciences – ICLS 2024, edited by Robb Lindgren, Tutaleni I. Asino, Eleni A. Kyaza, Chee Kit Looi, D. Teo Keifert, and Enrique Suárez, 1818–21. International Society of the Learning Sciences https://doi.org/10.22318/icls2024.651304.

Keune, Anna, and Kylie Peppler. 2019. “Child-Material Computing: Material Collaboration in Fiber Crafts.” In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL) 2019, edited by Kristine Lund, Gerald P. Niccolai, Elise Lavoue, Cindy E. Hmelo-Silver, Gahgene Gweon, and Michael Baker, 913–14. Lyon, France: International Society of the Learning Sciences.

Keune, Anna, and Kylie Peppler. 2019. “Materials‐to‐develop‐with: The Making of a Makerspace.” British Journal of Educational Technology 50 (1): 280–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12702.

Keune, Anna, Kylie A. Peppler, and Karen E. Wohlwend. 2019. “Recognition in Makerspaces: Supporting Opportunities for Women to ‘Make’ a STEM Career.” Computers in Human Behavior 99 (October):368–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.013.

Keune, Anna, Kylie Peppler, and Maggie Dahn. 2022. “Connected Portfolios: Open Assessment Practices for Maker Communities.” Information and Learning Sciences 123 (7/8): 462–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-03-2022-0029.

Kolodner, Janet L. 2004. “The Learning Sciences: Past, Present, Future.” Educational Technology 44 (3): 34–40.

Letourneau, Susan M, Dorothy T Bennett, ChangChia Liu, Yessenia Argudo, Kylie Peppler, Anna Keune, Maggie Dahn, and Katherine McMillan Culp. 2021. “Observing Empathy in Informal Engineering Activities with Girls Ages 7–14.” Journal of Pre-College Engineering Education Research (J-PEER) 11 (2). https://doi.org/10.7771/2157-9288.1354.

Morales-Navarro, Luis, Yasmin B. Kafai, Francisco Castro, William Payne, Kayla DesPortes, Daniella DiPaola, Randi Williams, et al. 2023. “Making Sense of Machine Learning: Integrating Youth’s Conceptual, Creative, and Critical Understandings of AI.” In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference of the Learning Sciences – ICLS 2023, edited by Paulo Blikstein, Jan Van Aalst, Rita Kizito, and Karen Brennan, 1640–49. International Society of the Learning Sciences. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2305.02840

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2019. “Recommendation of the Council on Artificial Intelligence.” OECD Legal Instruments. OECD. https://oecd.ai/en/assets/files/OECD-LEGAL-0449-en.pdf.

Peppler, Kylie, and Diane Glosson. 2013. “Stitching Circuits: Learning About Circuitry Through E-Textile Materials.” Journal of Science Education and Technology 22 (5): 751–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-012-9428-2.

Peppler, Kylie, Anna Keune, Maggie Dahn, Dorothy Bennett, and Susan M Letourneau. 2020. “Designing for Empathy in Engineering Exhibits.” In Proceedings of the 2020 Constructionism Conference, edited by Brendan Tagney, Jake Rowan Byrne, and Carina Girvan, 80–81. ACM.

Pinkard, Nichole, Sheena Erete, Caitlin K. Martin, and Maxine McKinney De Royston. 2017. “Digital Youth Divas: Exploring Narrative-Driven Curriculum to Spark Middle School Girls’ Interest in Computational Activities.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 26 (3): 477–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2017.1307199.

Built Environment Education for Children And Youth: Scoping the Field

Marta Brkovic Dodig, Angela Million, Rosie Parnell

Built Environment Education (BEE) for children is a dynamic yet fragmented field, characterized by a diversity of approaches and initiatives across museums, architecture centers, cultural organizations, design sectors, universities and schools (Brković Dodig, 2018; Million et al., 2018; Parnell et al., 2008). However, this lack of connectivity has posed challenges to the consolidation and development of a cohesive BEE framework. This paper seeks to address this fragmentation by presenting the scope of a study aimed at defining BEE as an educational field. It explores the theoretical and practical dimensions of BEE while situating it within broader educational frameworks. A forthcoming handbook – Built Environment Education for Children and Youth: Establishing the Field – captures and synthesises the findings of the study, seeking both to learn from and to bring together the ever-growing global BEE community (Brkovic Dodig, Million, Parnell, forthcoming).

First efforts to foster collaboration and knowledge-sharing have gained momentum through international initiatives. The Alvar Aalto Institute’s “Soundings” workshops (2004-2007) (Parnell, 2004) and the “Get Involved” symposium at the Venice Architecture Biennale (since 2012) or the 1st International Biennial of Education in Architecture for Children and Young People – LUDANTIA (2018) (Navarro Matínez et al., 2018) are notable examples of attempts to bring larger groups of practitioners together. These events revealed a strong demand for support, collaboration, and the sharing of experiences. However, documentation of processes and international dissemination of practice-based research in BEE remain relatively scarce, hindering the field’s ability to exchange practices and insights globally.

The purpose of this study is to provide an overview of BEE, from its historical contexts, through its global practices, towards a framework that situates BEE within the broader educational landscape (Brković Dodig et al., 2020; Million et al., 2019; Million & Parnell, 2017). By theorising its pedagogical foundations and identifying its unique contributions, this research aims to lay the groundwork for the recognition of BEE as a distinct educational field. Furthermore, this work seeks to open the field to empirical research and generate new insights, laying the groundwork for a robust pedagogical framework.

This paper focuses on describing the overall research design and delves into the pedagogical underpinnings of BEE as a continuous and evolving discourse. It argues that now is the right time to define the field of BEE pedagogy (Million & Hock, 2020; Parnell, 2010), given the increasing recognition of its importance in fostering children’s spatial awareness, creativity, and engagement with their built environments. It contributes to establishing a shared pedagogical foundation for BEE, inviting practitioners and researchers to participate in an ongoing dialogue to shape its future.

The research design underlying this study forms the foundation for both the analysis and the structure of the resulting handbook (Brkovic, Million, Parnell, forthcoming). It begins with a broad overview of the BEE field, examining its theoretical underpinnings, sources of motivation, and historical development. Empirical literature on the impacts of BEE provides additional insights into its importance and effectiveness in fostering children’s engagement with their built environments.

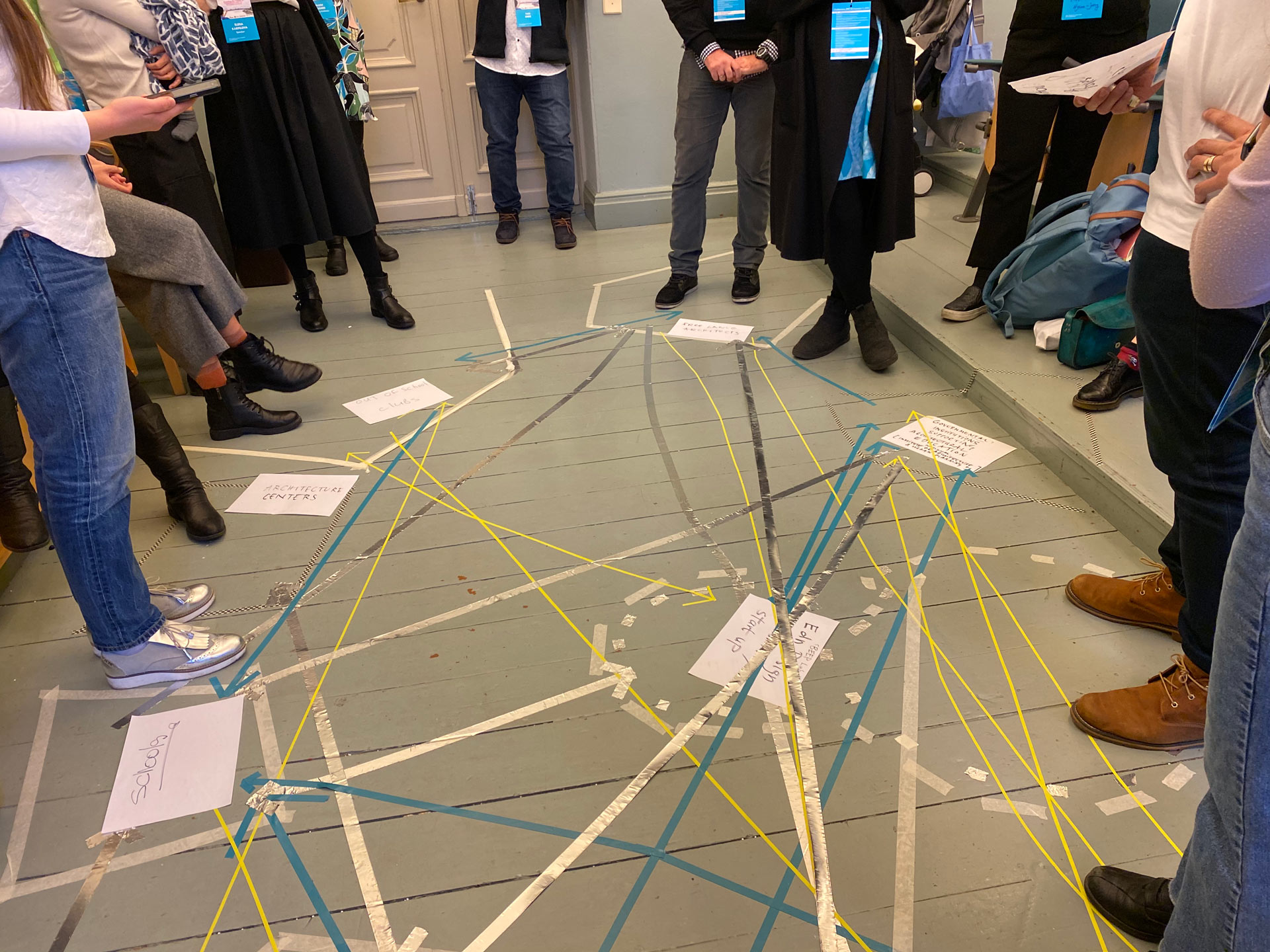

To capture the diversity of practices, the study incorporates interviews with BEE practitioners within various institutional settings – including museums, architecture and built environment centres, academia, private initiatives and organizations, out of school clubs and schools – complemented by desk-based document analysis and literature review. Further insights were drawn from internal workshops with BEE practitioners (Figure 1) and initiatives such as the Golden Cube competition, organized by the International Union of Architects (UIA) Architecture and Children Working Group since 2011, and Ludantia, the 1st International Biennial of Education in Architecture for Children and Young People held in Spain in 2018, which showcased projects primarily from the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking world.

Workshop on BEE institutional settings and framing policies during the ARKKI-Conference in Helsinki, 2019. Source: authors

Contributions from colleagues in Africa and Asia enriched the research, though the inherently local nature of BEE—often communicated in native languages and tied to specific cultural contexts—posed challenges to achieving fully balanced global representation (Figure 2). While the study acknowledges a global north and Anglo-centric perspective, particularly in its beacon studies, it successfully includes examples from other regions, such as Japan, Indonesia, South Korea, Singapore, China, India, Iran, Egypt, Mexico, Argentina, Costa Rica, and Turkey.

Workshop with BEE practitioners on global conditions, gaps and future action, Berlin, 2019. Source: authors

The core research explores the work of BEE providers, categorized by types of institutional settings, including schools, museums, architecture centers, design practices and community organizations. It investigates their motivations, policy frameworks, program formats, and pedagogical tools, as well as the challenges and successes experienced by those working in the field. The analysis is further supported by the presentation of two to three beacon studies, offering in-depth accounts of successful practices and the conditions that enabled them.

The success of BEE relies on the diverse and interconnected system of providers that bring a wide range of perspectives, resources, and expertise to the field. Each provider type contributes uniquely to BEE, offering specialized approaches while often collaborating with others to achieve shared goals. Our research identified and explored six key categories of providers:

Networks and Private Practice

Networks and private practitioners play a pivotal role in BEE by facilitating tailored programs and creating platforms for collaboration. These independent efforts often bring innovative approaches to education and focus on specific community needs, drawing from the unique expertise of their members.

Out-of-School Clubs

Out-of-school clubs provide flexible and informal learning environments where children can explore built environment topics through creative and hands-on activities. These programs often emphasize accessibility and personal interpretation, fostering a strong connection between children and their local surroundings.

Primary and Secondary Schools

Schools integrate BEE into their curricula through project-based learning, interdisciplinary approaches, or extracurricular activities. From early childhood education to secondary levels, these programs engage students in understanding, analyzing, and designing their built environments, often aligning with broader educational goals.

Universities

Universities contribute to BEE by offering outreach programs, research initiatives, and teacher training that incorporates the built environment as an educational resource. They serve as a bridge between professional disciplines and community education, fostering aspirations and awareness of spatial design.

Museums

Museums dedicated to architecture, urban studies, or cultural heritage provide immersive learning experiences through exhibitions, workshops, and interactive displays. These institutions act as hubs for intergenerational and community-based learning, connecting historical and contemporary perspectives on the built environment (Brković Dodig, 2018).

Professional Bodies and Architecture Centres

Professional organizations and architecture centers support BEE by developing educational materials, hosting public events, and advocating for inclusive design practices. These entities often facilitate collaborations between practitioners, educators, and policymakers, emphasizing the importance of informed public engagement in spatial development.

While each provider type has distinct strengths, overlaps among them highlight opportunities for collaboration. Specifically, schools emerge as central partners to all other institutional settings examined in this study, reflecting the aim to integrate and enhance BEE within school education. Private initiatives and networks, including freelance architects and architecture enthusiasts, also frequently collaborate across most institutions, leveraging their flexibility to deliver BEE content effectively. In contrast, institutions like out-of-school clubs or museums focus on their specialized yet continuously evolving BEE curricula, programs, and formats.

Public bodies, including city and town administrations, regional and state-led initiatives, though not categorized as standalone providers, play a vital role in supporting BEE. They often fund programs, set policy frameworks, and provide logistical support, enabling the work of other providers. This interconnected educational landscape of providers and supporters illustrates the collaborative nature of BEE. Strengthening partnerships between these actors enhances the reach and impact of programs, fostering a more cohesive and inclusive approach to built environment education.

In order to define BEE as a distinct educational field, it is essential to capture and describe its pedagogical foundations. This not only positions BEE in relation to other fields of education, such as arts education or education for sustainability, but also highlights its unique contributions to fostering spatial literacy and critical engagement with the built environment.

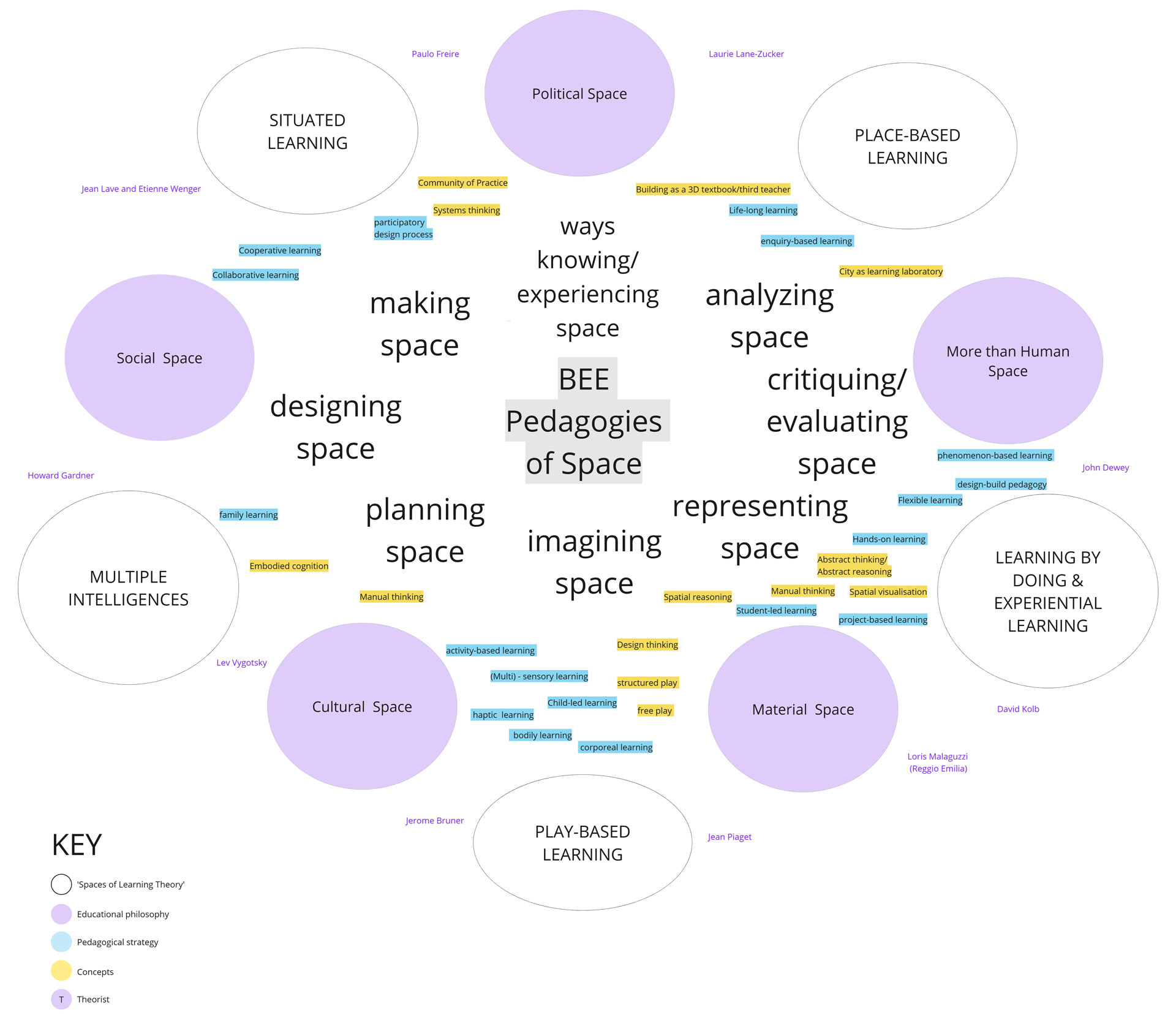

The pedagogical foundations of BEE reflect a rich interplay of educational concepts and methodologies (Figure 3), derived from the study of six institutional settings. Through our research into the practices of various providers, we constructed a conceptual framework illustrated through a figure that represents the pedagogical underpinnings of BEE. This diagram is not exhaustive; it does not encapsulate all institutional settings or the full breadth of BEE providers, and individual actors may associate with different aspects of the framework to varying degrees. The identified concepts, theorists and strategies have been explicitly named in the interviews and documents of the providers, while the educational philosophies also include terminology assigned by us the researchers based on the presented BEE work.

Pedagogical Underpinnings of BEE. Source: authors

We conclude that the core of BEE – as understood by its practitioners – is rooted in philosophies and theories of situated, place-based and play-based learning, coupled with frameworks such as multiple intelligences and learning by doing. Each of these philosophies can be interpreted to sit comfortably within a holistic understanding of experiential learning, as espoused by Beard & Wilson (2018). This foundation supports active, hands-on, and experiential methods that enable learners to engage with political, socio-cultural, and more-than-human worlds. These methods extend from the local to the global, emphasizing the material spatial world while prioritizing values such as social and environmental justice, inclusivity, and reciprocity.

BEE pedagogies, as seen in the practice of BEE educators studied, aim to develop knowledge, skills, understanding, and attitudes that revolve around ways of knowing and experiencing space. Key aspects include designing, making, and planning spaces, as well as analyzing, evaluating, representing, and imagining them. These practices ought to enable learners to form a holistic understanding of their built environment and its implications for society and ecology.

The learning theories underpinning BEE also take a pragmatic, ecological orientation, embracing and extending cognitive, constructivist, and socio-cultural theories of learning. These approaches foreground the role of material, political, and more-than-human spaces in processes of learning. The so-called ‘folk pedagogies’ (Bruner 1999) , of individual BEE practitioners reflect a range of different emphases regarding the various ‘spaces of learning theory’ and educational philosophies represented in this diagram. Existing learning theories and educational philosophies are synthesized and reinterpreted in the context of BEE, providing a fresh theoretical and pedagogical framework, which is further refined and clarified in the forthcoming handbook. Through its flexibility and adaptability, BEE addresses the unique demands of specific educational contexts.

Built Environment Education (BEE) is an evolving field characterized by a dynamic range of providers, pedagogical approaches, and diverse practices, all united by a shared vision of fostering spatial literacy and meaningful engagement with the built environment. By consolidating the scope of BEE and theorising its practices, this work seeks to establish it as a distinct and recognized educational field. Developing BEE presents both opportunities and challenges, including the need for broader global representation, the integration of new theoretical perspectives, and the continuous adaptation of pedagogical tools to address the demands of a changing world. As we continue to shape the field of BEE, we invite you to engage with the accompanying handbook, scheduled for publication in 2025. This resource offers in-depth insights into the pedagogical and practical dimensions of BEE and provides a foundation for ongoing exploration and dialogue. We encourage you to reflect on how your work aligns with the frameworks and practices discussed. This conclusion is not a definitive endpoint but an open invitation to collaborate, contribute, and advance the field together.

References

Beard, Colin, and John P. Wilson. 2018. Experiential Learning: A Practical Guide for Training, Coaching and Education. London: Kogan Page Publishers.

Brković Dodig, Marta. 2018. “Built Environment Education for Children – Museums in Focus.” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Urban Design and Planning 171 (1): 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1680/jurdp.16.00014.

Brković Dodig, Marta, Sarah Klepp, and Angela Million. 2020. “Cultural Heritage as Built Environment Education Resource: Pupils and Teachers Evaluating Learning within Lost Traces Project.” In Education Applications & Developments V. Advances in Education and Educational Trends Series, edited by Mafalda Carmo. Lisbon: inScience Press.

Brković Dodig, Marta, Angela Million, and Rosie Parnell. Forthcoming 2025. Built Environment Education for Children and Youth: Establishing the Field. London: Routledge.

Bruner, Jerome. 1999. “Folk Pedagogies.” In Learners and Pedagogy, edited by Jenny Leach and Bob Moon, vol. 1, 4–20. London: Open University Press.

Million, Angela, Thomas Coelen, Felix Bentlin, Sarah Klepp, and Christine Zinke. 2020. Educational Institutions and Learning Environments in Baukultur: Moments and Processes in Built Environment Education for Children and Young People. Ludwigsburg: Wüstenrot Stiftung.

Million, Angela, and Leonie Hock. 2020. “Quo Vadis Baukulturelle Bildung? Eine Einordnung der Baukulturellen Bildungspraxis.” Kulturelle Bildung Online, February 10, 2025. https://doi.org/10.25529/92552.538.

Million, Angela, and Rosie Parnell. 2017. “The Educative Planner.” disP – The Planning Review 53 (2): 78–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/02513625.2017.1341120.

Million, Angela, Rosie Parnell, and Thomas Coelen. 2018. “Policy, Practice and Research in Built Environment Education.” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Urban Design and Planning 171 (1): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1680/jurdp.2018.171.1.1.

Navarro Martínez, Virginia, Jorge Raedó Álvarez, and Xosé M. Rosales Noves, eds. 2018. LUDANTIA. I Bienal Internacional de Educación en Arquitectura para a Infancia e a Mocidade. Pontevedra: Colexio Oficial de Arquitectos de Galicia. https://issuu.com/colexiooficialdearquitectosgalicia/docs/ludantia_i_bienal_actas_web.

Parnell, Rosie. 2004. “Soundings for Architecture: An Educational Workshop for Adults and Young People.” Children, Youth and Environments 14 (2): 229–241.

Parnell, Rosie. 2010. “A Space for Learning, the Next Step—Education or Participation?” In A Space for Learning, edited by Rachel McAree and Alice Clancy. Dublin: Irish Architecture Foundation.

Parnell, Rosie, Judith Torrington, Lisa Procter, Nikki Ward, and Clare Elliott. 2008. The Change Project: Engaging Children and Young People with Architecture and the Built Environment. Executive Summary. Report for the Paul Hamlyn Foundation.

CLIMANIA - Creating Climate Change Literacy Through a Co-produced Board Game

Claudia Carter and Simeon Shtebunaev

The CLIMANIA board game laid our ready for 2-6 players. Photo: BCU

Climate change is a complex issue affecting all people and sectors. Much research exists explaining the challenges and trends from across multiple disciplines, yet policies and political actions globally, nationally and locally to keep global warming below dangerous levels are only slowly forthcoming. Similarly, climate change knowledge, debate, training and action amongst professionals and the public are still astonishingly marginal or poor. Specifically, awareness of the contributions to accelerated climate change by the built environment (including old housing stock) alongside transport, is lagging behind expected emission improvements to which the UK (and other countries) have committed to achieve by 2030 and 2050 (CCC 2024). In terms of suitable responses, urban retrofitting, for example, is not yet at the forefront of policy, public awareness or action (Harrop 2018). At the same time, especially young people suffer from climate anxiety and what an uncertain future means for them, leading to mental and physical health problems and feeling disempowered (Wu 2020).

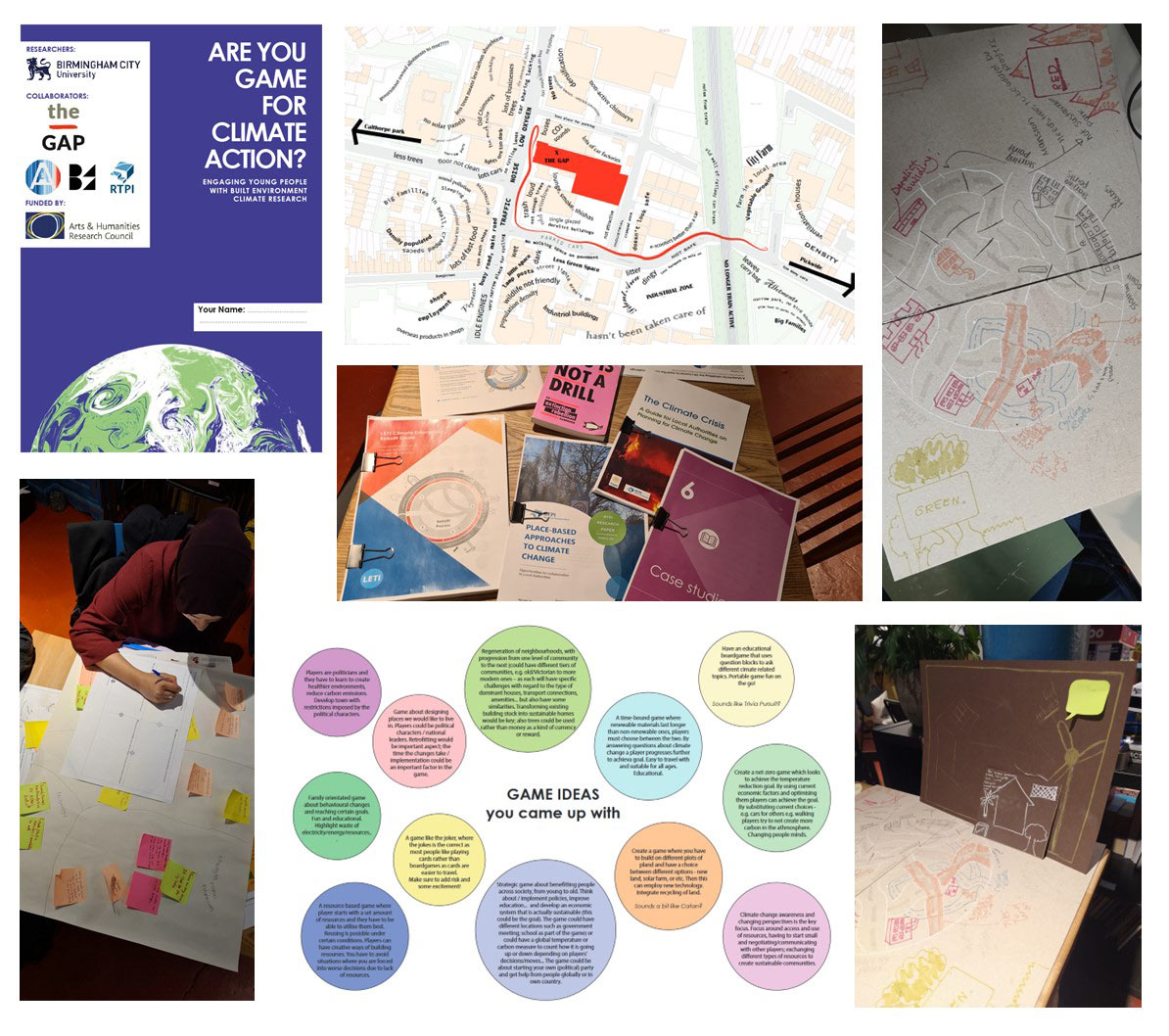

In 2021, in connection with the preparations for the climate conference COP26 in Glasgow, the opportunity arose to be part of a set of short projects funded by the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council aimed at engaging young people in climate literacy and action. Adopting ‘think global, act local’ (Geddes 1915), we focused on a local Birmingham ward in the top 10% most-deprived wards nationally, with an above average young population. The Balsall Health area has a post-industrial built profile with aging buildings, unkept urban environment yet some imposing Victorian buildings signalling past grandeur. Unaided, local climate action may fail to fully understand how climate research can be relevant to neighbourhood action and their homes, in an area of pressing issues such as low air quality, dirty streets and poorly insulated buildings.

We recruited thirteen teenagers, aged 14-18, by partnering with a local youth café and art centre – GAP Arts – tapping into existing community connections and youth networks. Our other project partners were Anthropocene Architecture School, the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI) West Midlands and the Birmingham Architectural Association. The Climate Action Game project ran seven two-hour workshops between November 2021 and January 2022 to produce the game prototype with additional refinement and testing continuing until March 2022. The first four workshops presented game-making basics and climate literacy about challenges faced by the construction and built environment sector. The participating teenagers received training by planners, architects and a climate activist and, supported by the two lead researchers, also acted as peer-researchers to collect further information from their friends and local community about key issues discussed. The final three workshops, facilitated by visual artists and academics, developed the boardgame prototype which was then tested and refined through engaging 100+ local people via intergenerational community game events and the Retrofit Balsall Heath community development group which emerged during this time and which has been using and playing CLIMANIA to aid their work.

Resources, Experiential Research Findings, and Game Development Activities during the Climate Literacy and Game-making Workshops, November-December 2021. Collage by Claudia Carter, drawing on photos taken by the project team.

We used a STEAM[1] and Design-Thinking infused co-design approach (Burns et al. 2020; Carter et al. 2021) drawing on our action research experience to help the young people develop climate literacy, research skills, game design and visual art skills and inspired them to mobilise climate action. Planning, architecture and arts professionals supported various workshops, adding variety of methods, voices and styles to the learning, sharing and co-producing activities. Refreshments and snacks were also offered for each of the late afternoon to early evening sessions, creating a welcoming and nurturing atmosphere for the teenagers who attended the project workshops after a full school day. The recruited participants were also paid for their time (in vouchers based on living wages for the age group), signalling appreciation of their time and input and their status as project partners.

From Prototyping and Testing to Launching CLIMANIA, January-March 2022. Collage by Claudia Carter, drawing on photos taken by the project team.

The key output, a playable board game ‘CLIMANIA: The Climate Action Game’, focuses on retrofit within an urban sustainability context (neighbourhood scale). The game’s name and focus and the prototype’s basic design, rules and features were decided by the participating teenagers and then translated, designed and refined into the final game by the project coordinators. CLIMANIA is for 2-6 players and includes different types of knowledge questions that need answering about climate change (amber coloured fields and 99 question cards) and retrofit (green coloured, 45 question cards) to move from one of the six available homes (bungalow, flat, detached, semi-detached, end-terrace, mid-terrace) near the edge of the board to the middle (a safe communal area) and on the way aiming to gain five retrofit parts for their chosen home respectively. We drew the technical details in the game from existing technical guidance and used 21 retrofit options based on current technologies and available graphics (LETI 2021). These retrofit solutions relate to five aspects/areas of home retrofit: the roof/loft space, openings (windows, doors), the build fabric (walls, floors), services and systems (heating, cooling), water (supply, use) and renewables (solar systems).

Furthermore, the reality of big or unexpected climate change related events were integrated through ‘Changing-Planet’ scenarios (red fields and 18 cards) and ad hoc social, environmental, economic and political scenarios through purple Joker fields and 18 scenario cards. This mix of game elements along with timing the play duration (i.e. the world is heating up and hence limited time for climate action) reflects some of the real-life complexity and dynamics and makes the game educational but also varied and fun. The resulting gameplay allows players to adopt a competitive or collaborative approach, closely mirrroring real-life climate co-operation scenarios.

Professionals and students play a giant version of CLIMANIA at the Architecture is Climate Exhibition at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London, March 2023. Photo: Simeon Shtebunaev

We found that the STEAM and Design Thinking approach and engagement techniques enabled successful co-design with young people. Furthermore, the serious play and game design proved to be effective means to disseminate complex climate research, create climate awareness, and stimulate climate action. CLIMANIA has shown to be engaging and break down complex ideas; and for people from all kinds of walks to learn through curiosity and enjoyment. The game can be played as competitively or collaboratively as the players wish and decide. Green and amber cards need reading out by a co-player for whoever’s turn it is to answer; this way all players hear and learn during each turn; some questions and situation cards spark discussion and group involvement to further highlight the benefits of communal elements and the need for equity in climate mitigation and adaptation.

The game making process duration was tight and the materials and knowledge shared largely pitched at undergraduate level. We did not oversimplify or skirt round issues but explained and were supportive as required. The process provided participants with choices (e.g. different working groups and elements) to help make the sessions and collaboration interesting and manageable. We also used existing frameworks, materials and templates (e.g. for climate change teaching and for the design of the game) to be time and resource efficient and not reinvent the wheel.

In its first two years the game was downloaded over 2000 times in 60+countries across the globe. Locally and nationally, the game has been used as a tool for education in formal and informal settings, for engagement, advocacy, discussion, action-informing, and as a professional development tool. Simeon Shtebunaev also featured in a British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) podcast for BBC Radio 4’s ‘Arts & Ideas’ series on COP26 talking about the game-making process and its relevance. In November 2022, ‘CLIMANIA – the Climate Action Game on Retrofit’ received a commendation in the TET Inspire Future Generations Awards as the best online resource; and in 2023, we won the RTPI’s Sir Peter Hall Award for Excellence in Research and Engagement for the CLIMANIA game and the research-engagement project which produced it. We thus feel that the project achieved its aims of providing climate education about the built environment through the game-making process and for the output to act as a teaching tool and a community game to understand how the players’ local built environment can adapt and help achieve the climate targets set by the Paris Climate Agreement.

Social media campaign images created by Simeon Shtebuanev for the launch of CLIMANIA in March 2022 featuring short quotes by the project coordinators, team members and participants. Collage: Claudia Carter

References

Bertrand, M. G. and I. K. Namukasa. 2020. STEAM education: student learning and transferable skills, Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 13 (1): 43–56.

Burns, K., C. Carter, Z. Ahmed and S. Sisay. 2020. The use of design thinking in non-design contexts – a journey and experience. In: M. Evans, A. Shaw and J. Na (Eds) Design Revolutions: IASDR 2019 Conference Proceedings. Volume 4: Learning, Technology, Thinking. Manchester Metropolitan University, The International Association of Societies of Design Research, pp. 708–718. ISBN 978-1-910029-62-6. http://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/626771/.

Carter, C., H. Barnett, K. Burns, N. Cohen, E. Durall, D. Lordick, F. Nack, A. Newman and S. Ussher. 2021. Defining STEAM approaches for Higher Education, European Journal of STEM Education (Special Issue STEM & Arts Education), 6 (1): 13. https://doi.org/10.20897/ejsteme/11354.

CCC. 2024. Progress in reducing emissions: 2024 Report to Parliament. Climate Change Committee, 18 July 2024. https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/progress-in-reducing-emissions-2024-report-to-parliament/

Geddes P. 1915. Cities in Evolution. London, UK: Williams and Norgate.

Harrop, J.N. 2018. Sustainability Awareness and the Built Environment, PhD Dissertation, Cranfield University.

LETI (Low Energy Transformation Initiative). 2021. Climate Emergency Retrofit Guide, available at: https://www.leti.uk/retrofit.

Wu, J., G. Snell, and H. Samji. 2020. Climate anxiety in young people: a call to action, The Lancet Planetary Health, 4(10), e435-e436. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30223-0

Contextualizing Architecture Education: Resonant Learning Processes in Lima’s Informally Built City

Hannah Klug

“No one educates anyone else, no one educates themselves alone, people educate one another, mediated by the world.”

—Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1967)

As global crises mount, the necessity of reevaluating humanity’s relationship with the environment and the world we inhabit becomes increasingly urgent. Starting from this holistic perspective, education, particularly in architecture and urban planning, holds a significant responsibility, and offers potential to foster critical and inclusive spatial practices for future generations. This ongoing research investigates how collaborative learning in informal urban areas can transform architectural education, challenging traditional knowledge paradigms, redefining the planner’s role, and equipping future practitioners to tackle present and emerging urban challenges. It raises the question of how the informally built can be used as an educational setting in architecture education to co-produce knowledges that contribute to a contextualized architectural practice.

Overview on Alto Perú neighbourhood. Understanding the urban context, Lima, Peru. Photo: IntuyLab

Lima, Peru, home to nearly eleven million inhabitants, represents the focal point of this study. The city’s high urban informality—seventy percent of its built environment is informally built—and its socio-political instability challenge traditional approaches to planning and architecture. Despite thirty-three architecture schools in the metropolitan area, curricula often reflect westernized frameworks inherited from colonial governance, limiting their relevance to Lima’s multidivergent realities. The informally built city, characterized by high levels of uncertainty, is frequently treated as a subject of research, rather than a collaborative learning space, however these parts of the city show innovative strategies of spatial adaption and habilitation. After Fujimori’s dictatorship ended in 2000 Lima’s activist student movement of independent architecture collectives regained strength, aiming to free academia from conservative perspectives, and connect architectural education with the city’s peripheral areas—primarily informal settlements. Embedded in this context, this research reimagines Lima’s informally built city as a resonant learning environment and analyses an exemplary collaborative learning space, created in the context of the Design-Build project, Centro Comunal Alto Perú, a pedagogical experiment initiated by the former student collective intuyLab, in collaboration with local and international universities, architecture students, a local NGO and the families of the neighbourhood Alto Perú. The study aims to analyse the pedagogical space, generated by these experimental learning initiatives, through their spatial practice and the knowledge co-produced within it.

Construction site in Alto Perú neighbourhood, Lima, Peru. Photo: Hannah Klug

The pedagogical space created by these learning initiatives can be described as a “learning assemblage”—a concept developed by the geographer McFarlane (2011), which recognizes the city as a space where critical urban learning occurs spontaneously and continuously. Here, learning takes place through the transformation, linking, and reflection of lived experiences (Kolb&Kolb, 2005), and, due to its collaborative nature is understood as a co-production of knowledges between different actors, including students, teachers, and neighbours (Polk, 2015; Watson, 2014). In this context, the concept of “space” plays an important role, as a relational construct created through the interplay of interpersonal relationships and the built physical environment (Lefebvre, 2005, Löw, 2022). Understood in this way, the city becomes a resource for knowledge co-production, shaping the experiencing and learning subjects within it, while being shaped by them in return. Spatial practitioners have a special role and responsibility in this ongoing interplay, as they design the built environment, which in turn influences the subject’s experiences in space. As a “resource,” however, the city as a vibrant interactive learning platform is not infinitely available, and its preservation depends on our active and conscious stewardship to maintain it (Rieniets et al. 2014).

Resonant Learning Space

To better understand the phenomenon of the pedagogical learning space formed between individuals and their environments, this study draws on “Experiential Learning Theory” (Kolb&Kolb, 2005) and “Resonance Pedagogy” based on the sociologist Hartmut Rosa’s theory of “Resonance” (Rosa, 2022), both of which identify the social and built context as fundamental components of the learning process. According to Rosa, resonance is a “specific mode of relating to the world” that emerges through interactive and meaningful experiences between individuals and their environments. The quality of lived experiences shapes how individuals perceive and act in the world, influencing how they learn and develop, both personally and professionally. This relationship determines whether individuals view challenges as opportunities or threats (Rosa, 2022)—a key factor in problem solving within unstable urban contexts.

Contextual Knowledge Co-production

Unlike the academic context, knowledges in the informally built city are often co-produced through fluid processes characterized by constant uncertainty. These processes are rooted in co-production (Watson, 2014; Polk, 2015), which encompass collaborative efforts where urban actors share knowledges, experiences, and competencies to create solutions for societal problems (Polk, 2015). For architecture and urbanism, such situated and contextual spatial knowledge is essential for developing projects that sensitively respond to the real needs of a place and its inhabitants.

Based on a hermeneutic approach, the qualitative research examines how the informally built city as pedagogical learning space can be described and what are the knowledges co-produced in it? These questions were addressed through a case study on the collaborative learning project, The Rolling Community Centre of Alto Peru, led by the student collective intuyLab.

Construction site. Collaborative carpenter workshop with youngsters in the neighbourhood, Lima, Peru. Photo: Hannah Klug

In 2015 the Peruvian student collective IntuyLab initiated an eight-year long participatory design project to build a community centre in the Alto Perú neighbourhood, a place marked by drug dealing and violence in public space, as well as vulnerable housing conditions. The project integrated co-production processes involving local architecture students, neighbours, and a local NGO, alongside partnerships with international universities. Over several phases, participants engaged in tactical urbanism, placemaking interventions, and participatory design. The process was characterized by uncertainty and conflict, that led the organisers to rethink and change the project several times. A mobile version of the community space was collectively built and completed with a group of youngsters from the neighbourhood in 2023, who are nowadays activating the Rolling Community Centre and the neighbourhood with cultural and sportive activities for the younger ones. Through participatory observation, collaborative working on the construction site, and a series of semi-structured interviews conducted by the author, insights were drawn on the experiential learning space, which was created throughout the project.

A Processual Learning Space

The collaborative learning experiences in the constantly changing context of the informally built city focus on the processual—something that is defined as certain or planned can change at the very next moment. Here, the only constant seems to be the process itself. In the context of the analysed project this insight was difficult to grasp for students and teachers, who had a settled time schedule, in contrast to the statements from locals, which demonstrated that they did expect difficulties within the process. The community centre project, which started with an architectural design in 2018, experienced several moments of crisis—caused by internal conflicts of interest, shootings in the neighbourhood, and the global pandemic of Covid 19—before finally being developed as a mobile version that ultimately responds even better to the needs of the children, the possibilities of the neighbourhood, and the NGO. Architecture practice, which usually aims at the completion of an object or a space, finds it challenging to recognise an open-ended process as the core of a project. The project showed that moments of crisis and conflict were essential to reflect on the ongoing processes, inviting opportunities to realise adjustments.

Learning by doing. Carpenter workshop with youngsters of the neighbourhood, Lima, Peru. Photo: Hannah Klug

A Resonant Learning Space

Preliminary results from the qualitative analysis of the studied case reveals dimensions of a resonant pedagogical space–as defined by resonance theory–such as the experience of self-efficacy, or moments of uncontrollability identified by the students, teachers, and neighbours, which were later transformed by them into learning experiences. These findings suggest that the informally built city represents a pedagogical space capable of fostering significant learning experiences, which in turn have a significant impact on students’ professional practice. Key components such as self-efficacy, the role of uncertainty, and crisis experiences stand out prominently. These components, based on the current state of research, seem to strengthen the resonant axes between the learning subjects, and the learning content, as well as the institutional context, thereby creating a positive relationship between the participating students, and the surrounding world—in this case the neighbourhood marked by urban informality.

A Space of Multiple Knowledges

As mentioned above, in the informally built city, collaboration between architecture student collectives, neighbours, NGOs, and universities unfolds through sometimes unstable and unplannable processes. Within these dynamics, multiple knowledges are co-produced, often serving as a valuable supplement to architecture students’ university education. The knowledges they acquire in the city are project-orientated action knowledge, technical expertise in construction methods, and social skills related to communication and collaboration. It’s interesting to note that the knowledges identified align with the resonance axes of Rosa’s model, offering valuable insights for teaching practice to consciously stimulate specific learning processes among architecture students.

The Rolling Community Centre in action. Activating the street with art classes. Photo: Proyecto Alto Perú

Mutual Transformation: Learning Means to Teach – Teaching Means to Learn

In the unstable context of the informally built city the roles of the various actors, especially the teachers, are repeatedly scrutinised. Recognising the informally built city as a learning space requires a sufficiently flexible curriculum that can adapt flexibly to local conditions. Due to its direct practical relevance, teachers also act here as executive planners. Their actions and behaviour as project coordinators are perceived by the students as a direct learning reference. Therefore, it is not just learning-by-doing, but also teaching-by-doing. This again emphasises the holistic approach that the learning context of the informally built city requires. The collective learning experience amongst all participants create a sense of belonging to the project, and with it a social sustainability for the realised project. In Alto Perú, participating youngsters are independently installing the rolling community centre nowadays in public spaces to implement activities for the younger children there.

Lima’s informal urban areas offer profound opportunities for collective resonant learning, providing architecture students with experiences that reshape their professional practice and perspectives, fostering contextualized knowledges, and preparing future planners to address urban challenges with sensitivity and resilience. Resonance theory offers a valuable lens for advancing architectural education, emphasizing the importance of meaningful interactive learning experiences that transform both individuals and the environments they engage with. These conclusions offer an expansion of Rosa’s theoretical model and challenge the traditional role of the teacher, positioning them as a collaborative participant in the learning process. How these conclusions can be integrated into current pedagogical practice warrants further exploration and is part of a bigger study.

References

Kolb, Alice Y., and David A. Kolb. 2005. “Learning Styles and Learning Spaces: Enhancing Experiential Learning in Higher Education.” Academy of Management Learning & Education 4 (2): 193–212. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2005.17268566.

Lefebvre, Henri. 2005. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. . Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Löw, Martina. 2022. Raumsoziologie. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Wissenschaft.

McFarlane, Colin. 2011. Learning the City: Knowledge and Translocal Assemblage. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Polk, Merritt, ed. 2015. Co-Producing Knowledge for Sustainable Cities: Joining Forces for Change. New York: Routledge.

Rieniets, Tim, Nicolas Kretschmann, Myriam Perret, Kees Christiaanse, and Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich, eds. 2014. Die Stadt als Ressource: Texte und Projekte 2005-2014, Professur Kees Christiaanse, ETH Zürich. Berlin: Jovis.

Rosa, Hartmut. 2022. Resonanz: Eine Soziologie der Weltbeziehung. 6. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Watson, Vanessa. 2014. “Co-Production and Collaboration in Planning—The Difference.” Planning Theory & Practice 15 (1): 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2013.866266.

Fields of Play as Instruments for Cohesion in the Social Spaces of Diverse Societies

John Wood

In his book The Uses of Disorder first published in 1970, Richard Sennett argues that a defining feature of adult identity as opposed to the adolescence is the ability to identify oneself based on action rather than attributes or characteristics, to be equipped with the skills to navigate contradiction and multiplicity and understand one’s own identity as inextricably related to the people and places around us (Sennett 2021, 135). Sennett argues that the urban environment provides a healthy disorder which enables the development of these skills and sensibilities. However modern urban social spaces, increasingly privatised, segregated and tightly controlled by singular public or private organisations (Bauman 2013, 3), bear little resemblance to the disorderly, cosmopolitan city that Sennett wrote about in 1970, so today’s and indeed tomorrow’s environmental designers can no longer simply rely on the messy, organically evolved urban environment to provide the civic complexity required to support the social development of its citizens. They will instead need to find their own methods for creating it.

An activity we are familiar with when it comes to productive disorder is play. A quick glance through the literature on play will tell you all about the important developmental processes which take place when children play: they develop emotional resilience and independence, they learn to be good leaders as well as good team players, they develop important organisational and negotiation skills and test their physical capabilities (Huizinga 1970, 20, Cohen 2019, chap. 3). Through play children learn their strengths and also their limits, where they are able to trust their own ability as well as learning where they might need to collaborate or rely on others. Are these not the same attributes that Sennett sees as essential for all citizens to develop to enable them to positively contribute to a caring society? And yet so often we neglect to appreciate the significance of play outside of the realm of small children and the important contribution it might make to society at large.

Contemporary thinking around play is often directed at child’s play, a form of play mostly practised with a degree of exclusivity in that it is the main focus of the child’s attention for the duration of the activity. It is unusual to see non-children engaging in this kind of play other than perhaps when playing with children. Many of the most familiar forms of non-child play are sports or exercise-based activities, but these also can be problematic as the degree to which free play occurs within sports or exercise can be very limited. This kind of exclusive, inflexible, rule-bound ‘play’ is of relatively limited value in a social context because of its fixed boundaries, brittle rule structure and exclusive grounds for participation. Play is socially richer when it is inclusive and invites participation from across a broad age and ability range and socio-cultural spectrum, when it is dynamic and can therefore adapt to suit spatial influences and it can be engaged with on a range of levels, from spectating or low stakes involvement to deep immersion, levels which can also vary over time.

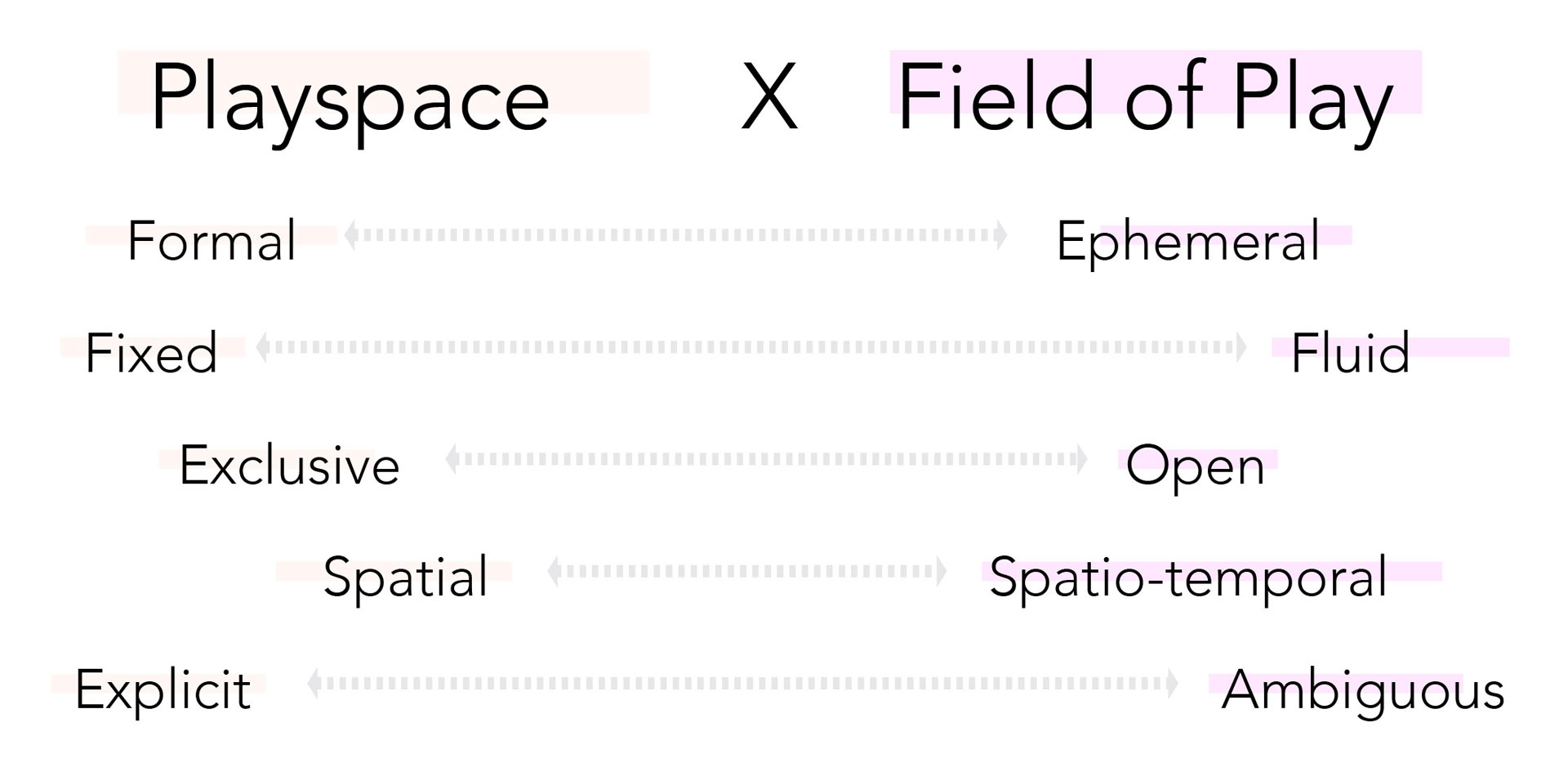

Defining characteristics of a field of play as compared to a play space.

In his book Play Matters play scholar Miguel Sicart shows us why it is the underlying attitudes and activities manifested in play which determine its true character, not the form of the play itself:

“Play has to begin somewhere, and it does so by occupying a context with its form, typically the rules of the game… Because play happens through form and is a way of being in the world, the cultural capital of the act of creating the form of play has dramatically increased… The form of play obsesses our culture. Of course, this is the wrong obsession, since what is important about play is not its form, which will, after all, mutate as part of play itself, but the activity or the attitude, that is, the process of engaging with the world and oneself through play.” (Sicart 2014, 84)

The social benefits of play are greatest where play is open, agile, flexible and ambiguous. Here the notion of a field of play becomes valuable. In contrast with a play space, which Sicart defines as “a location specifically created to accommodate play,” (Sicart, Play Matters, 51) fields of play are malleable. Play space is to some degree formally defined and fixed whereas fields of play are fluid, defined by the activities which take place within or affordances of the space itself and can easily change over time without physical intervention. A play space is exclusive in that there is a degree of expectation upon anybody entering that they engage in play more or less in accordance with the way it is intended for the space. A field of play is ephemeral and can transform to accommodate newcomers, it can appropriate an existing space at a moment’s notice, overlap with other spatial fields and disappear in an instant.

In the interests of making the concept more tangible, I propose the following working definition for fields of play:

A spatial system which has been appropriated or affords the possibility of its own appropriation through play.

This definition places emphasis on how a space is defined by the actions or expected actions of people rather than being defined by the physical characteristics of a space as we see in play space. It relates to physical characteristics only inasmuch as its physical characteristics provide opportunities for engagement between people and place, or more pertinently, between people in the spaces that they share. The characteristics which define a field of play might be ambiguous or non-specific, for example it may be simply the scale of a space which allows for activities to take place which would be difficult in other settings, or the presence of a visual connection between physically distinct locations like different levels. This ambiguity or openness is one of the characteristics which gives fields of play potential importance in a social context, removing barriers to participation and giving participants agency over the way that a space can be used and therefore understood.

This characteristic of the field of play, a space which is somewhat defined by the people who inhabit it, makes it an opportunity in the social spaces of diverse societies. Not only can these spaces provide a forum for different social groups to express their identity, they are also a place where that collective identity may interact with that of other social groups. These interactions allow social groups to become familiar with one another, understand each other, to learn to cooperate and even to manage conflict.

In order to understand the potential of these spaces more clearly I have analysed two key case studies: City Park in Bradford (UK) and La Friche in Marseille, (France). Both case study sites are in cities which can be to some degree characterised as places where immigrant communities have settled leading to a condition where there are distinct socio-cultural communities, living side by side. Through my case studies I sought to understand to what extent designers might use the concept of fields of play, to create conditions for vibrancy and social cohesion amongst cultural groups in the social spaces that they share.

In order to illustrate some of the elements of the field of play I will focus on an analysis of a particular space Plateforme at La Friche which is one of the main points of intersection between the site’s user groups. This abandoned tobacco factory turned creative campus presents itself as a public, community-facing space, an attitude which feels uncommon in the modern, commercial city. In the organisation’s own words:

“La Friche offers a variety of open-air spaces that are open to the public every day. These include areas for play and athletic activity; green spaces for picnicking, an area for playing pétanque; and benches and lounge chairs for sunbathing, reading, daydreaming… There’s even a barbecue!”

—lafriche.org 2020, ‘useful information’

Figure 2 shows two photographs of Plateforme. In each of the photographs the space can be seen as a field of play, in the daytime activated by children with roller skates and scooters, in the evening by young adults attending a music event in the former factory. The space also accommodates passers-by, creating potential for all of these groups to overlap at certain times leading both to chance encounters which serve to increase interaction and provide opportunities for bonds to be created amongst users.

Transformed in accordance with a design by ARM Architecture, Plateforme provides a carefully curated assemblage parts, all of which combine to provide fertile ground for fields of play. These may be categorised as:

- Loosely curated functional elements (skate ramps and picnic tables).

- Areas of unprogrammed space. (circulation routes, terraces and stairs)

- Implied but ambiguous spatial definition (a three lane running track, some changes in ground cover and partial barriers).

- Possibilities of chance interactions (a pedestrian through-route including a staircase and visually interconnected levels).

- Playful signalling (murals and street art).

Observing how the space is used it is clear that alongside intended uses of the space there are an equal number of unintended uses – parents using the skate ramps as a seating space while their children play, children using queue control barriers as football goals and passers-by using corridors and stair landings as terraces for people-watching. Many of these uses wouldn’t have been explicitly foreseen at the design stage, but the approach the designer has taken allowing spaces to overlap, using hard-wearing materials and simple, versatile forms and leaving spaces which are unprogrammed and loosely defined, all contribute to creating a rich ecosystem in which fields of play may emerge.

The challenges faced by the next generation of environmental designers are manifold, from fighting climate change to addressing shortcomings in fire safety; decolonialisation; to negotiating the relationship between artificial intelligence and society. Arguably the most urgent challenge in a society increasingly under threat to fear and hostility is the need to design places which promote acceptance and cohesion, to understand how our urban environment becomes an infrastructure which supports us in developing sophisticated social skills, educates us how to deal with conflict and creates the necessary conditions for learning how to care about one another. The notion of a field of play can help us to move away from thinking of social spaces in terms of fixed spatial definition or prescribed uses and towards thinking about how environmental designers can provoke chance encounters, facilitate agency and foster healthy relationships within and across social groups. Put simply, as instruments for cohesion in the social spaces of diverse societies.

Plateforme, La Friche la Belle de Mai in Marseille designed by ARM Architecture (now Caractère Spécial) shown in daytime and evening use depicting two distinct ‘fields of play’. Image by the author

Bibliography

Bauman, Z. 2013. Globalization : The Human Consequences. Wiley.

Bingham-Hall, J. 2022. “Cultural field : Kristell Filotico and Atelier Roberta’s addition to La Friche in Marseille throws the tension between spaces for the public and cultural production into sharp relief.” Architectural Review 1492: 40-49.

Cohen, D. 2019 The development of play. Routledge.

Huizinga, J. 1970 Homo Ludens: A study of the play element in culture. Temple Smith.

Jacobs, J. 1962. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Vintage.

Kristell Filotico Architecte. 2016. “Kristell Filotico Architecte.” Accessed 11 August 2024. https://www.kristellfilotico.com.

La Friche. 2020. “La Friche la Belle de Mai” Accessed 24 February 2025. https://www.lafriche.org.

Sennett, R. 2021. The Uses of Disorder: Personal Identity and City Life. Verso Books.

Sicart, M. 2014. Play Matters. The MIT Press.

Environmental urgent pedagogies for training and supporting the educators

Claudia Carter and Emma Jones

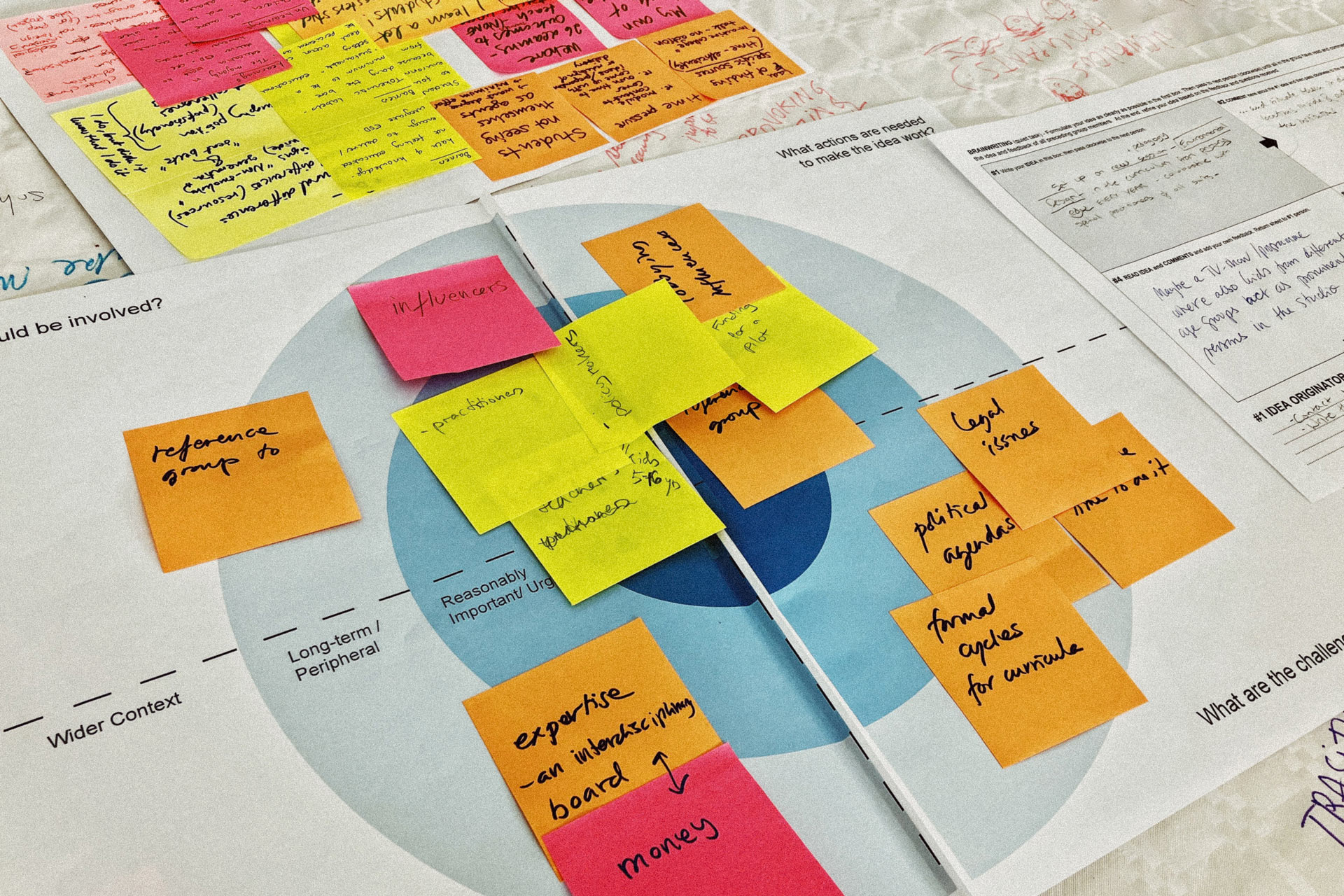

Figure 1: A photograph taken during the workshop, documenting the radial diagram task to explore a specific idea in terms of its participants, resources, actions and challenges. Photo: Anette Göthlund