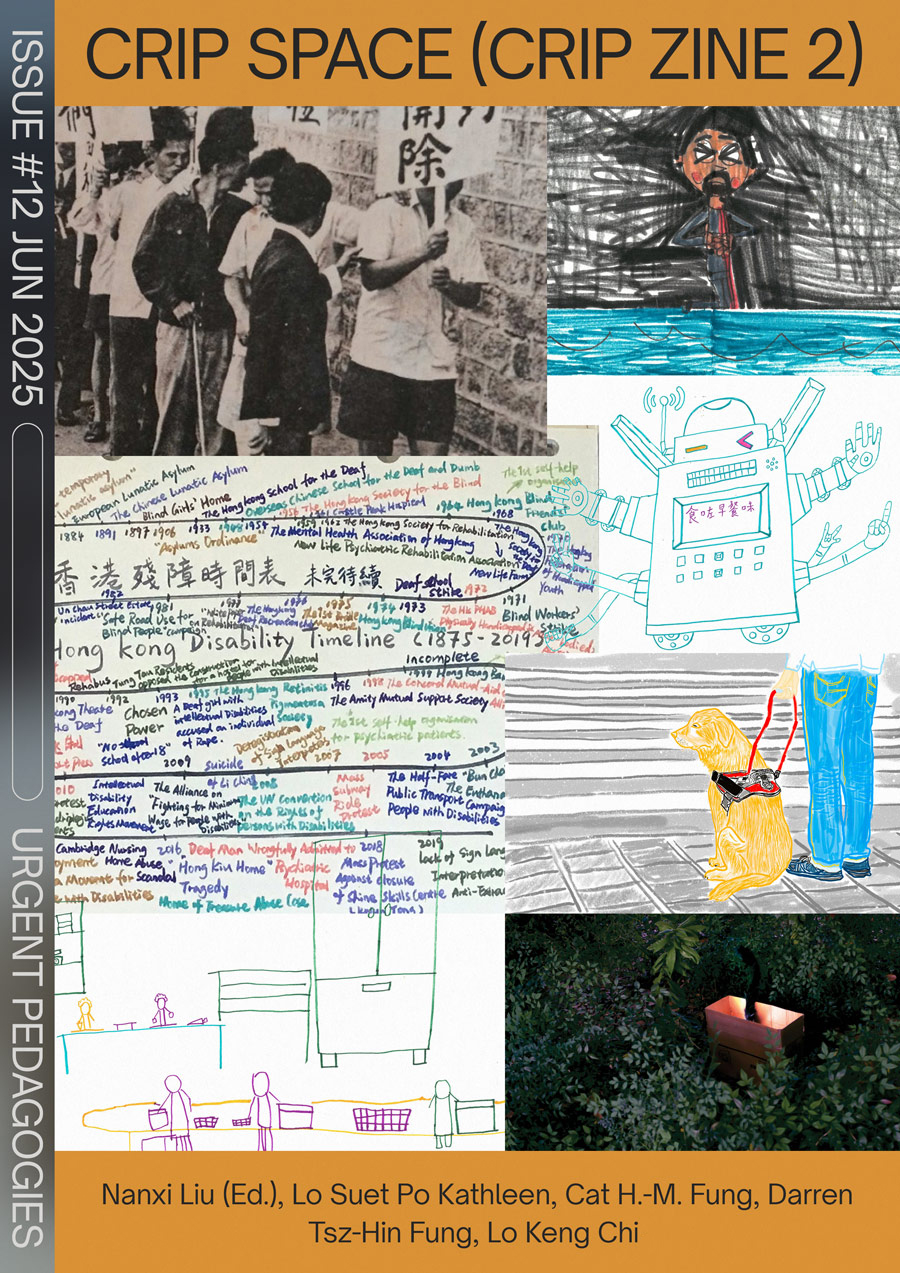

Viewing Disability Justice Through the Lens of Disability Spaces

Nanxi Liu

CATEGORY

Nanxi Liu examines the evolution of Disability spaces in Hong Kong, critiques the medical model’s dominance in defining Disability and its impact on funding and service provisions.

(Content Warning: This article discusses potentially distressing topics such as suicide, sexual violence, and discrimination.)

“Voyager, there are no bridges, one builds them as one walks.”

—Gloria Anzaldúa [1]

One morning in March 2013, I attended my first monthly dance gathering with the Symbiotic Dance Troupe in Hong Kong as a volunteer. At that time, I had only been in Hong Kong for six months to study, and my Cantonese was at a beginner’s level; I could only manage the simplest self-introductions and expressions of thanks. The prospect of applying for internships at local arts organisations seemed nearly impossible, as almost all of them required proficient Cantonese communication skills. I was fortunate to find this first volunteer opportunity because the organisation was willing to accept a mainland Chinese person who did not speak Cantonese. Due to the language barrier, I became particularly attentive to body language.

At that first gathering, I danced in a circle with two or three dozen dancers with Disabilities, including wheelchair users, blind people, Deaf participants, those with intellectual Disabilities, and others with physical Disabilities. Each person used movement to describe their name, physical state, and feelings, expressing the areas where they hoped to be understood and cared for. For the first time, I felt acutely aware of my lack of body language skills, whilst simultaneously marveling at the confidence and brilliance radiating from the dancers with Disabilities. During the two-hour gathering, my body and mind seemed to enter a world where no words were needed, and we all understood each other.

At the end of the gathering, I realised that the staff were nervously reminding everyone to board the Rehabus [2] on time and return to their care homes. My body returned to reality, and I was about to reach out to assist a wheelchair user in leaving when a staff member stopped me, saying, “You don’t need to offer help unless she asks for it. They have their own abilities and choices.” This statement made me reflect for a long time and sparked my desire to stay in Hong Kong to learn and work.

Having grown up and lived in mainland China for twenty-five years, I had always been surrounded by six relatives with Disabilities: a cousin who reportedly suffered from intellectual Disabilities due to a severe fever in childhood; a visually impaired male cousin; an uncle who had mobility issues due to polio; an intellectually Disabled woman who was arranged to marry my uncle; the daughter of that uncle and his wife; and an uncle who had long-term mental health issues and had previously committed domestic violence. All six relatives always stayed at home. In the rural areas of China, where support for people with Disabilities is nonexistent, my grandmother and aunts took on the labour of caring for the Disabled family members for many years.

As my grandmother got older, the responsibility of caring for my uncle was shifted to an “arranged marriage”. There has always been a “tradition” in rural China of introducing Disabled people from different villages to marry each other. Without institutional support, families have to rely on relatives and friends to help one another. However, the woman my uncle was arranged to marry, my aunt-in-law, did not seem capable of taking on the caregiver role. I still vividly remember my quiet and withdrawn aunt-in-law often bedridden when I was 12 years old. Later, when my aunt-in-law had a child, the family anxiously murmured that the child must have inherited her intellectual Disability.

One day, I suddenly overheard my father and a different aunt crying as they spoke. My uncle had committed suicide. I didn’t have the chance to understand him more. My aunt told me that my uncle had tried many times before—jumping into a river, drinking pesticides—each time the family worked hard to “save” him, even sending him to a psychiatric hospital in a nearby town, but this time, there was simply no way to help. At that time, still in high school, all I could think about was getting into university so I could leave. I became one of those “fortunate ones”, distancing myself from my family and the responsibilities of caregiving.

After arriving in Hong Kong, I encountered another mainland Chinese person on my way back home one year, someone who also wanted to stay in Hong Kong. As we chatted about our impressions of the city, the other person said, “I’ve always been curious why there are so many Disabled people in Hong Kong; I often see many blind individuals, wheelchair users, and people with various Disabilities on the streets.” I was taken aback by this comment, yet it also brought a sense of clarity, and I responded, “Because the streets and public spaces in Hong Kong are accessible to people with Disabilities, whilst most Disabled people in mainland China are stuck at home and rendered invisible.”

Throughout the years of engaging and collaborating with Disabled friends in Hong Kong, I have carried a deep sense of guilt within me. Whilst I received learning, care, and support from the Disabled community in Hong Kong, my grandmother and aunts were still tirelessly caring for our Disabled family members. I felt as though I was unable to do anything to help them. I could only comfort myself by saying that I wasn’t ready yet and that I needed to work hard in Hong Kong to learn everything I could about Disability.

From 2013 onwards, I have been involved in work related to Disability arts in Hong Kong. Initially, I worked for an NGO called Centre for Community Cultural Development (CCCD) that promotes inclusive and community arts, which helped establish the Symbiotic Dance Troupe. I worked there full-time for about six to seven years, and during this time and now, I have been working with the Hong Kong International Deaf Film Festival.

In such a small NGO that lacked consistent funding, the scope of my work in arts administration was incredibly broad. It encompassed everything from applying for grants, organising budgets, coordinating events, promoting activities, recruiting volunteers and participants, contacting instructors, booking venues, arranging sign language interpreters and audio descriptions, booking Rehabuses, ensuring that events were accessible, documenting through photography, compiling event reports, organising financial statements, answering questions from funders, addressing financial audit inquiries, and ultimately, managing the final project report.

Essentially, every inclusive arts project was a one-person arts administration job. Furthermore, due to long-term funding being at least 30 to 50% less than the proposed budget, I had to continuously apply for new project funding each month whilst simultaneously managing approved projects. My overtime hours were consistently high, sometimes exceeding 140 hours a month. One time, I went over three months without a day off. There were times when I worked until 5 am and then returned to work at 11 am. Year after year, I was physically and mentally exhausted, yet I had to keep motivating myself, telling myself that this work, promoting inclusive arts, was incredibly meaningful. If I didn’t do it, it would affect future funding and even jeopardise the already fragile finances of the NGO.

During the most hectic years of my work, particularly from 2019 to 2021, the Hong Kong Social Welfare Department launched the “Arts Development Fund for Persons with Disabilities” for the first time. This was Hong Kong’s first annual funding programme focused on developing the arts for people with Disabilities. Prior to this, we had to compete fiercely with numerous mainstream arts organisations and independent artists for the Hong Kong Arts Development Council’s project funding—which was available only twice a year—or seek support for artistic development from social welfare and medical funds, whilst also navigating collaborations with various welfare organisations and self-help groups for people with Disabilities. Long-term, we found ourselves caught in the middle of the arts and social welfare sectors, feeling insufficiently “artistic” and not as capable as those organisations providing the most basic “Disability welfare”.

The application guidelines for the “Arts Development Fund for Persons with Disabilities” stated that its goal was “[…] to enhance arts knowledge of PWDs [people with Disabilities], foster their interests in arts and explore their potential through the provision of elementary and/or continuing arts programmes and help PWDs who have great artistic potential to strive for excellence and develop their career in performing, visual and creative arts.” [3]

In those years, CCCD, the organisation that I worked for, received funding for four consecutive 18-month Disability arts projects. The funding amount was approximately double that of the usual Arts Development Council grants, but the workload was several times greater. Not only did we have to hold activities or courses every month, but we also had to submit detailed reports every three months, detailing the number of “service users” and “beneficiaries”, the duration of each activity, and explaining any discrepancies and changes between what was initially planned with reality. Every small adjustment would lead to incessant inquiries from the Social Welfare Department staff. I experienced instances where I was questioned over the phone for an hour, repeatedly answering every question on the forms. At the 12-month and 18-month project milestones, we had to submit even more detailed reports and financial statements, meticulously calculating every cent spent. Each time we submitted a report, it was preceded and followed by countless phone calls.

I no longer resembled the person who initially participated in the monthly gatherings of the Symbiotic Dance Troupe, with the time and energy to engage in and enjoy moments of dancing, creating, and being inspired by friends with Disabilities. Instead, a significant amount of my time was consumed by navigating through endless forms and phone calls. After hanging up the phone time and time again, I just wanted to scream and cry, feeling on the brink of collapse. The completion of the projects, as evaluated by the Social Welfare Department, seemed more like a fulfillment of beneficiary quotas rather than a genuine effort to develop Disability arts or nurture Disabled artists. During those chaotic overtime hours, I experienced severe burnout, depression, and suicidal tendencies, and I had to seek help from a psychoanalyst at my own expense.

All of this led me to have significant doubts and confusion about my work and the so-called career in Disability arts. Consequently, I began reading relevant literature and attempted to write research proposals to apply for a PhD to study Disability justice and Disability arts in Hong Kong. However, after three consecutive years of applications to four different universities and five different potential supervisors in Hong Kong, I faced rejection every time. Feeling completely disheartened, I was fortunate to meet a group of friends who were equally concerned about Disability justice. Starting in March 2022, we formed a study group that initially met every two weeks to read Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s book Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice, whilst also discussing the current situation in Hong Kong. Later, with the support of Asia Art Archive, we published the first issue of Crip Zine. [4]

Crip Zine 1, photo by Nanxi Liu.

The term “Crip” has sparked a lot of internal discussions within our reading group. In Piepzna-Samarasinha’s book, it is used frequently, with a footnote stating:

“‘Crip’ is a word used by many people in disabled communities as a fuck-you, in-your-face reclaimed word, short for cripple— similar to how queers have reclaimed the word ‘queer’. Not everyone likes it or uses it; people have complex feeling about it, and it’s not great for abled people to use it.” [5]

This footnote has been very enlightening for me. On the one hand, I am deeply inspired by “Crip” as a redefinition of identity politics, and it can also serve as a verb to break old concepts and established frameworks. On the other hand, I remain reflective and vigilant about my privilege as a non-disabled person. Recently, I have noticed that more and more people are using the term “Crip” — due to a series of Crip Art events organised by the group named c.95d8 — including claims that, “Since we are all going to be disabled eventually, why don’t we put down the labels of ‘able-bodied’ and ‘disabled’ and embrace the Crip identity together?” [6], and even suggesting that Disability is a state that anyone can experience, asserting that everyone has “Crip time”, such as asking, “Is your period your Crip time?” Seeing these discussions raises questions for me. I understand that perhaps we need to find common ground to achieve some form of connection that transcends barriers, but at the same time, this amplified and generalised use of “Crip” may obscure or oversimplify the struggles faced by Disabled individuals who have long endured discrimination, pain, and poverty.

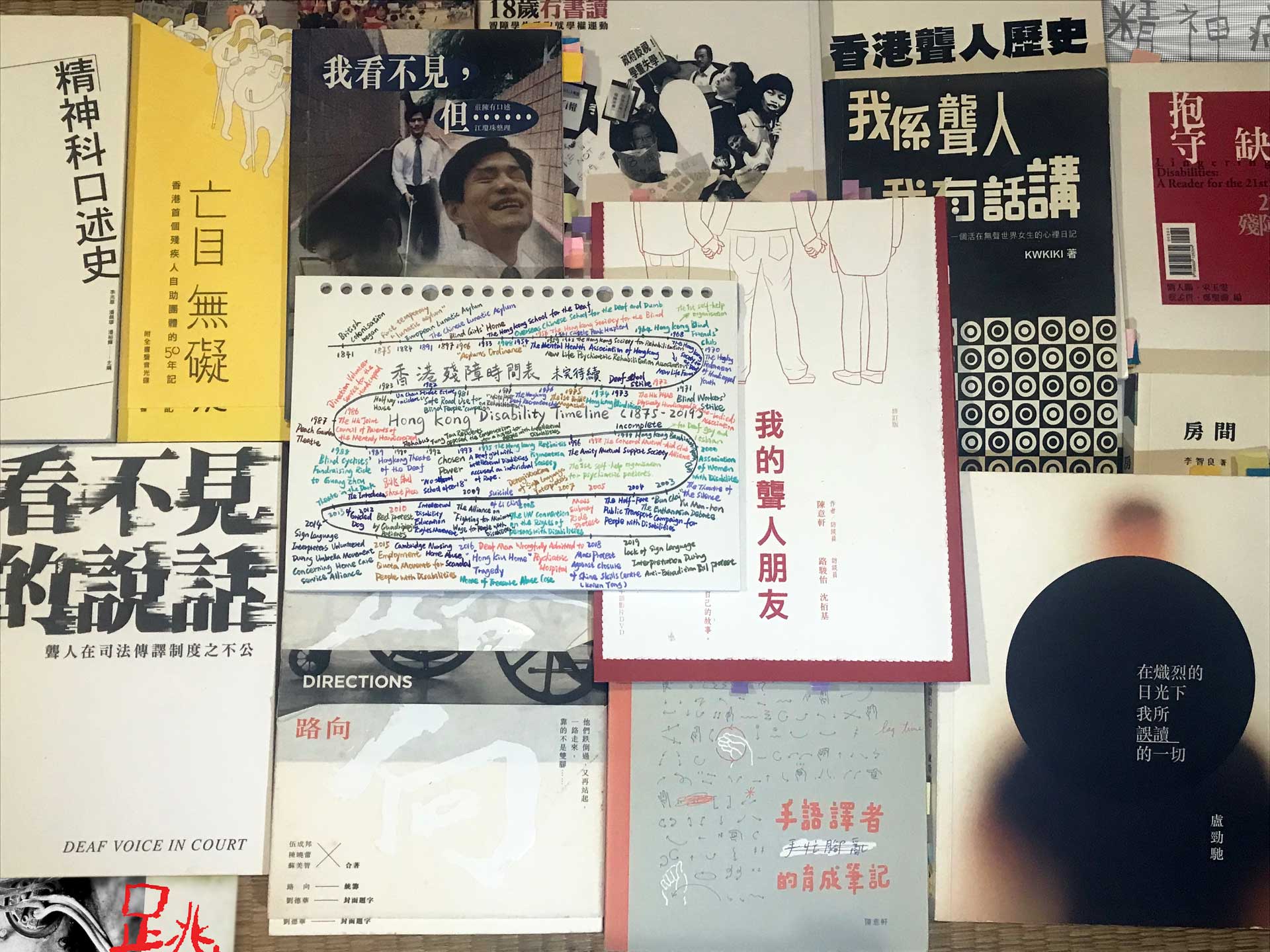

In the English-speaking world, there are rich discourses and literature on Disability studies, whilst the Chinese discourse on Disability studies in Hong Kong remains sparse. The current situation of Disabled communities in Hong Kong and the history of the Disability movement are still scattered across various timelines on the websites of Disability organisations and groups, institutional historical reviews, autobiographies of Disabled people, oral histories, and sometimes sensationalised news reports. Through the writing process of Crip Zine 2, we have collectively organised and discussed Crip Space. I have spent time reading and compiling a timeline of the Disability movement and history in Hong Kong. However, in just a few months, I have not been able to compile it completely, only the brief records of major events from 1875 to 2019. Through this timeline, I have felt the ongoing struggle of Disabled people in Hong Kong over the years, and I am pained by the persistent discrimination, violence, and tragedies that are ongoing.

“I described disability as a series of sites that include the spaces of the body but that extend into a more public arena of communities and institutions. If we think of disability as located in societal barriers, not in individuals, then disability must be seen as a matter of social justice.”

—Michael Davidson [7]

From the historical perspective of Disability spaces in Hong Kong, the earliest spaces were dominated by churches, doctors, and government-led social welfare organisations and service centres, where Disabled people were students, workers, service users, people who were “treated” or isolated, and also regulated. Former president of the Hong Kong Blind Union, Chong Chan Yau, recalled in his oral autobiography, “Those who provide services for blind people often treat them as their property, as if they have the right to control the destinies of others. They consider issues from the perspective of the institution’s reputation and self-esteem, without understanding or respecting our feelings.” [8] The earliest self-help organisation for Disabled people in Hong Kong, the Hong Kong Blind Union, was established in 1964 precisely because blind people were dissatisfied with the government and the services led by Hong Kong Society for the Blind, leading them to spontaneously organise and manage their own spaces.

The rise of the self-help Disability movement in Hong Kong is, on the one hand, a response to the oppression and neglect faced in Hong Kong, the extreme shortage of Disability services, and the limitations, barriers, exclusion and discrimination faced by Disabled people in education, survival, healthcare, employment, and living environments. For example: in 1971, blind factory workers protested against unreasonable wages; in 1973, students from a school for the Deaf went on strike demanding sign language education; in 1986, parents of people with intellectual Disabilities took action to establish a parents’ association in response to the shortage of services for adults with intellectual Disabilities; and in 2008, the “No School After 18 – Intellectual Disability Education Rights Movement”, initiated by students with intellectual Disabilities and their parents, objected to the Education Bureau of Hong Kong’s amendment to deny financial assistance and further education to students with intellectual Disabilities who had reached the age of 18, which became the first major legal battle for Disability education rights in Hong Kong.

Due to the inability to rely on the support and assistance provided by the system and institutions, more and more Disabled people, long-term patients, and caregivers have spontaneously organised together to establish self-help organisations and mutual aid groups. [9] At the same time, some self-help organisations have been inspired and influenced by overseas Disability movements. For example, in 1974, two blind representatives from the Hong Kong Blind Friends’ Club attended the 2nd International Federation of the Blind Conference held in West Berlin, where they learned about self-help movements for visually impaired people worldwide. Upon returning to Hong Kong, the Hong Kong Blind Friends’ Club suggested renaming their organisation to the Hong Kong Blind Union, emphasising the fight for rights rather than just engaging in social activities. Similarly influenced by overseas self-help movements, in 1993, four individuals with intellectual Disabilities and their parents travelled to Toronto to attend the People First international seminar, and after returning to Hong Kong, they founded Chosen Power, claiming to be “the first self-help organisation for friends with intellectual Disabilities in Asia that is not affiliated with any service unit”. The People First advocacy movement was originally founded in 1968 in Sweden by a group of parents of children with intellectual Disabilities. [10]

According to information from the Hong Kong Society for Rehabilitation’s online platform on self-help organisations, Shohub (launched in 2018), write that by the end of 2016, approximately 200 self-help organisations and about 100 mutual aid groups had been established across Hong Kong. However, the list of self-help organisations provided by the Hong Kong Society for Rehabilitation is entirely constructed within the framework of the medical model, categorising all Disabilities arbitarily under different “disease” entries. For instance, the list includes “hearing impairment” but does not mention “Deaf”, even though there is the Hong Kong Association of the Deaf. [11] Furthermore, the list shockingly includes “gender identity disorder” to refer to transgender people.

After the flourishing of self-help groups in Hong Kong during the 1990s, many of these groups transitioned into registered non-profit entities or companies. By 2001, the Social Welfare Department began to establish funding to support Disability self-help groups. Consequently, the number of self-help groups getting funding in 2001 was 38 groups, and this number increased to 104 groups by 2024. The funding applications, which occur every two years, are insufficient to support the ongoing operations of Disability self-help organisations, yet they influence many organisations to adopt a “welfare institution” model. To continue applying for funding, these organisations must fit themselves into the medical model’s definition of “patients”, as the key items in funding applications must specify who the “service users” are. Therefore, in the Social Welfare Department’s funding list, the Hong Kong Society of the Deaf, which advocates for Deaf identity, is categorised as serving “hearing-impaired individuals and their families”, whilst the Rainbow of Hong Kong Limited, which claims to voice for the rights and welfare of the “LGBT+” community, is categorised as serving “persons with gender identity disorder and their families”. Similarly, Gender Empowerment Limited, an organisation actively promoting transgender information, also falls into this category.

Operating a space in Hong Kong is extremely costly, requiring long-term investments in rent, workforce, and materials. Between limited funding and challenging realities, many Disability self-help organisations seem to be struggling to find a balance. Looking at the historical context of the Disability movement in Hong Kong, the development of rehabilitation policies under colonial governance involved significant participation from doctors and medical professionals in the early process of Disability organisations advocating for welfare, such as the Disability Allowance. For example, the founder of the Hong Kong Society for the Deaf, founded by Hong Kong’s first ENT (ear, nose and throat) specialist Dr George Choa Wing-Sien, suggested to the government in 1976 that “deaf individuals” be classified as “disabled persons”. Subsequently, in 1978, the Hong Kong Society of the Deaf called for a Deaf assembly advocating for Deaf people to receive Disability allowances.

Various practical limitations have made it difficult for Hong Kong’s Disability self-help organisations to operate outside the framework of social welfare funding. The development of Disability arts also largely relies on the spaces and funding provided by Disability welfare institutions. Disability arts are often framed as “expressing ability arts” or “inclusive arts”, with the former emphasising the potential of Disabled people to participate in artistic expression and the latter focusing on the inclusive participation of both Disabled and non-disabled people.

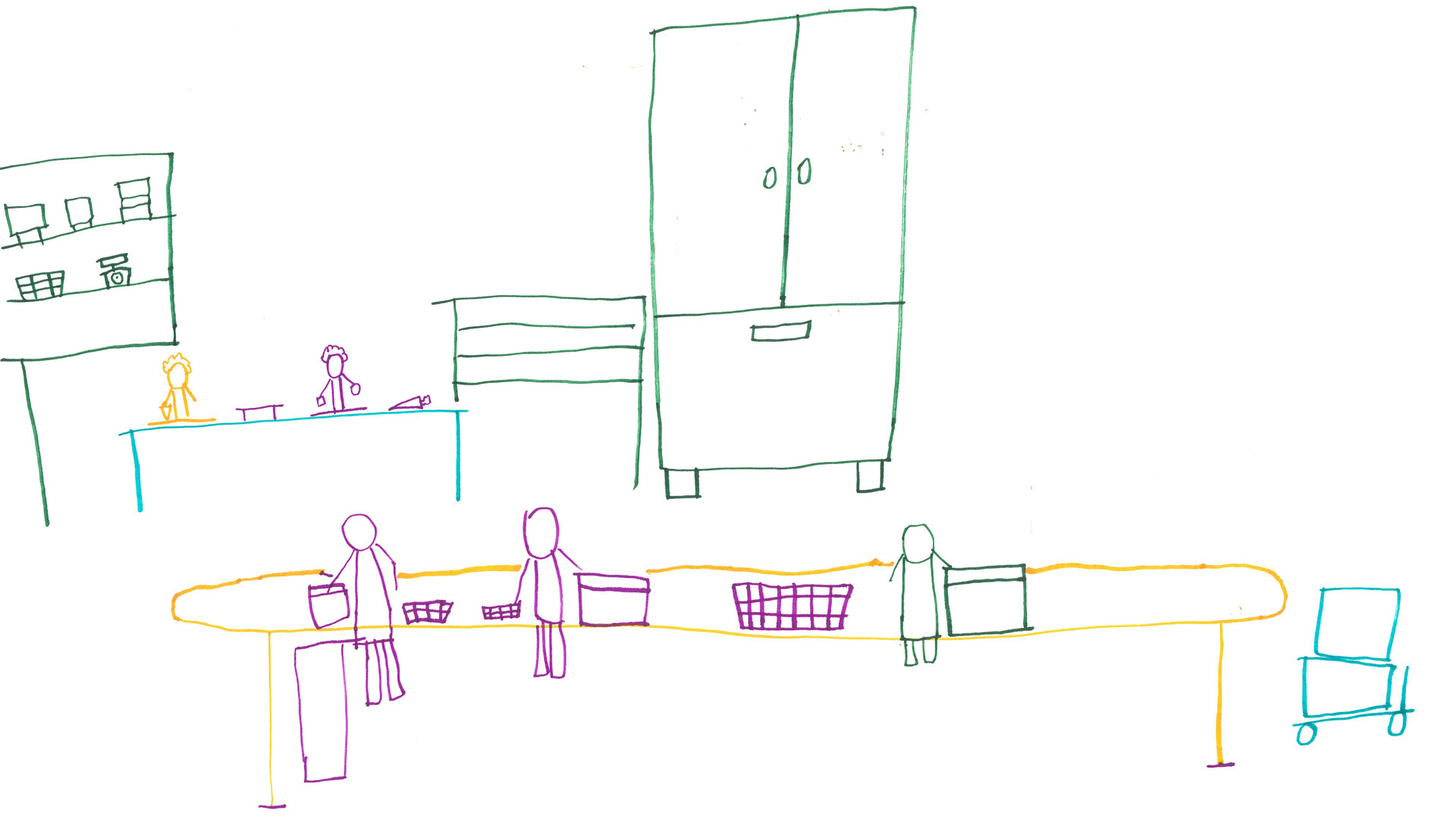

Sheltered workshop, drawing by Felix @weighty.design.studio, St James’ Settlement. Image courtesy of Weighty Design Studio

In Hong Kong, the spaces that are open and accommodating to Disabled people are far wealthier and more diverse than those in mainland China. There are special schools for Disabled children, vocational training centres for Disabled people, sheltered workshops [12], residential homes for Disabled people, Disability welfare organisations, and self-help organisations for Disabled people. From the Hong Kong Disability Timeline (1875-2019), we can see how many movements organised and led by Disabled people in the past have changed the public and opinion spaces of this city. For example, in 1981, blind people protested on the streets to initiate a movement for road safety, urging changes to the accessibility of public spaces and the installation of pedestrian crossing sound devices.

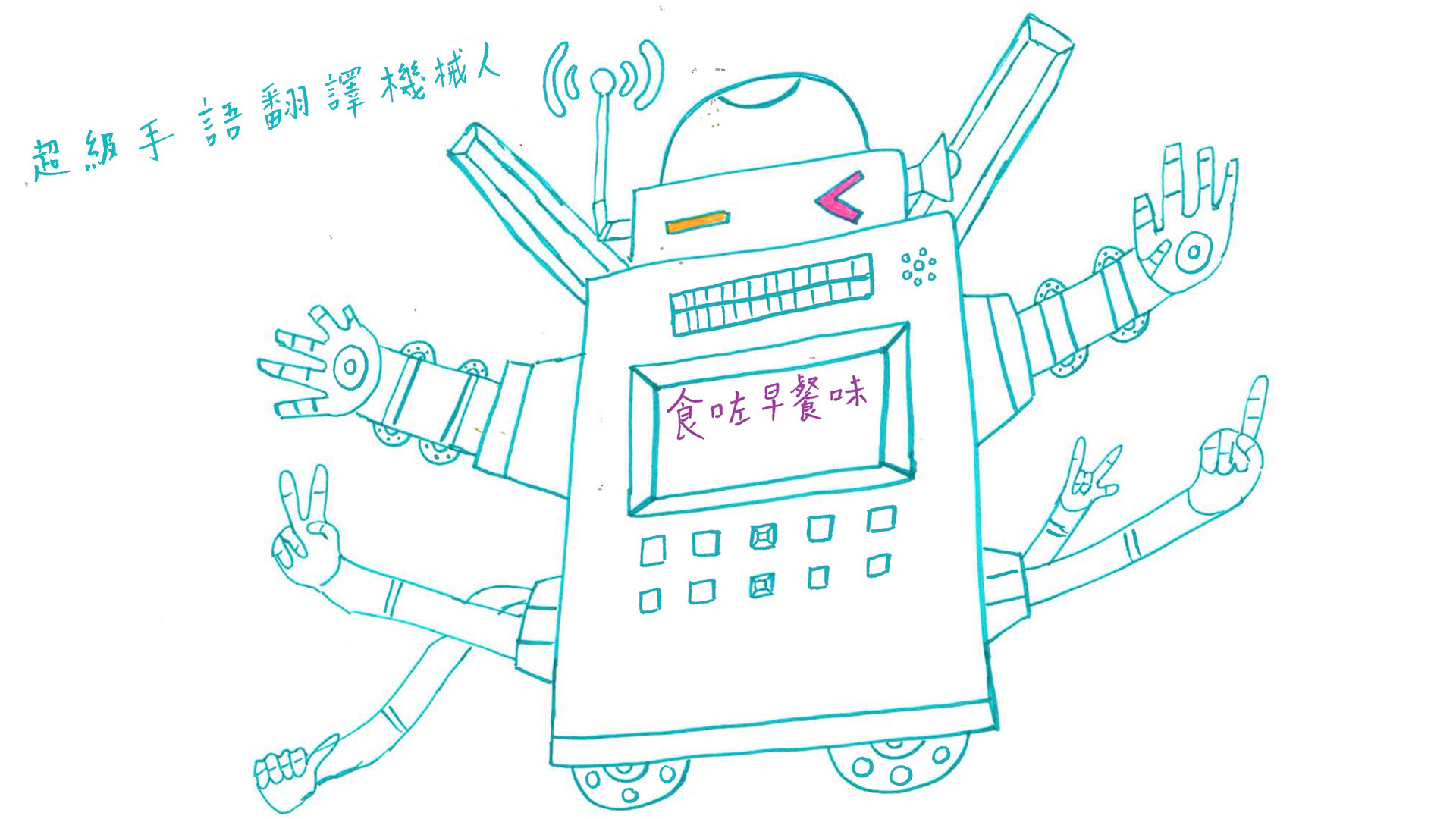

Due to the shortage of services for adults with intellectual Disabilities in Hong Kong in the 1980s, many people with intellectual Disabilities found themselves without options after graduating from special schools. Consequently, parents of people with intellectual Disabilities spontaneously organised to advocate for policy support from the government. When a “halfway house” (a term used by the Social Welfare Department to describe transitional dormitories for people with Disabilities) faced continuous protests from residents and was halted in Cho Yiu Chuen, people with intellectual Disabilities and their parents proactively held a press conference and protest titled “People with Intellectual Disabilities Are Also Human”, attempting to change societal misunderstandings and discrimination against people with intellectual Disabilities. Similarly, Deaf people and sign language interpreters have made continuous efforts to increase sign language interpretation in various fields, including news broadcasting, hospitals, clinics, and judicial institutions.

However, despite the development of rehabilitation policies in Hong Kong for nearly 50 years since 1976, many long-standing issues remain unresolved. One major issue is the chronic shortage of residential spaces in care homes, with long waiting times and poor living conditions. Meanwhile, the legal rights of Disabled people to be free from violence and abuse in care homes are not adequately protected. Since 2016, the waiting time for government-subsidised care homes was extended from 8 to 16 years, leaving many Disabled people who have not been allocated subsidised homes to reside in private facilities.

In subsidised homes, the minimum floor area per person is 8 square metres, whilst the “Residential Care Homes (Persons with Disabilities) Ordinance” has lowered this space standard to 6.5 square metres. [13] Consequently, the living conditions in private homes are even smaller and worse. Between 2014 and 2016, several reports surfaced regarding multiple private homes subjecting Disabled people to violence and abuse, including the notorious Hong Kiu Home tragedy [14], Cambridge Nursing Home Abuse Scandal [15], and the Home of Treasure Abuse Case [16]. When Disabled people sought legal recourse, they often found it difficult to receive fair treatment. For example, in 1993, a mentally Disabled Deaf girl testified in court against a person who raped her. During the trial, the survivor broke down under pressure, and the judge decided to terminate the hearing, allowing the defendant to be released on the spot. This incident sparked strong protests from many Disability groups, including the Hong Kong Joint Council of Parents of the Mentally Handicapped, which took over 10 months to formulate 17 recommendations for “assisting individuals with intellectual Disabilities to testify in court”. However, when the Hong Kiu Home tragedy occurred in 2014 and 2016—the founder of this private care home Cheung Kin Wah was charged for raping a female resident with Disabilities in 2014 and sexually violated two Disabled residents in 2016—the Department of Justice repeatedly deemed witnesses unsuitable to testify, leading to the withdrawal of criminal charges for sexual assault, leaving the survivors to pursue civil proceedings with their families.

Similarly, the judicial system’s unfair treatment of Disabled people has long been evident in the Deaf community. According to a report by Ming Pao newspaper, “From 1997 to 2016, there were fewer than 10 sign language interpreters qualified to serve in Hong Kong’s judicial institutions, whilst there are over 150,000 Deaf and hard-of-hearing people in Hong Kong, resulting in a ratio of 1 interpreter for every 3,000 Deaf and hard-of-hearing people.” [17] In 2016, there was an incident when the police, lacking knowledge of sign language and failing to seek assistance from a sign language interpreter, mistakenly sent Mr Liu, a Deaf person, to a hospital, which also failed to arrange for sign language interpretation, leading to Mr Liu being sent to a psychiatric hospital instead. [18]

Many Disabled people who cannot enter subsidised care homes or afford private facilities are forced to continue living with their families. On Chosen Power’s website, there is a list documenting 25 caregiver tragedies that occurred between 2010 and 2020, with sources from case records highlighted in Hong Kong news. [19] Many of those incidents involved both caregivers and those they cared for committing suicide or caregivers killing those that they cared for before taking their own lives. One of the most extreme and tragic cases was the 2019 Sai Kung murder case, where a cult leader and a mother abused her intellectually Disabled 21-year-old daughter to death under the pretext of “exorcism”. Each incident is heart-wrenching, stemming from desperate and helpless families.

“A representative from the Concerning Home Care Service Alliance pointed out that according to statistics, there are 200,000 cohabiting caregivers in Hong Kong, but the organisation believes that the actual number is much higher. They criticised the lack of caregiver-centred policies in Hong Kong, with only one policy requiring income and asset limits, which is a monthly caregiver living allowance of HK$2,400.” [20]

Meanwhile, the annual expenditure of the Social Welfare Department has risen from HK$90.5 billion in 2020-2021 to HK$127.4 billion in 2024-2025, yet the availability of residential spaces in care homes has not changed significantly, except for a slight increase in the number of nursing homes for severely Disabled people and assisted living facilities. Other types of residential units for people with Disabilities remain unchanged.

The standard Disability allowance is HK$2,095 per month and the highest is HK$4,190 per month. Those who are deemed “capable” of working in sheltered workshops receive a monthly wage (referred to as training allowance or incentive payment) of HK$850, which amounts to only HK$26.5 per day, falling short of Hong Kong’s statutory minimum wage of HK$42.10 per hour. In reading all this information, the news, data, and tragedies surrounding Disability spaces in Hong Kong, it prompts a profound reconsideration of the deep connections between Disability and structural violence, class, and unequal wealth distribution.

Facing such harsh realities, how do we continue to discuss Disability justice? How can we discuss identity politics but not also reflect on Disability from the perspective of social justice? Disability studies often emphasise that everyone will eventually become Disabled. [21] Regardless of whether one embraces a Crip identity, we are reminded by those who have suffered for a longer time, those who have been excluded or forgotten by society and systems that are in place, those who are continuously stigmatised in so-called “normal” society, and the countless Palestinians who are still experiencing a genocide and being debilitated by colonial oppression, over many decades. These reminders highlight that Disability is not just an identity; it is also a brutal reality of injustice and a hope for breaking power structures from the margins.

As I organise and read through all the materials related to Disability issues, I find myself constantly reflecting on my previous work and the current direction of discussions and efforts with my friends at Crip Zine. It seems that Disability space in Hong Kong is still in a process of negotiation between welfare systems and Disability rights advocacy. Embracing Crip as a proud Disability identity remains a minority within the Hong Kong Disabled community, and the Crip space we have discussed may not yet have fully emerged. However, by continuing our discussions and actions, I hope that Crip Zine can become a cultural and spiritual space that dismantles and deconstructs the misunderstandings, neglect, discrimination, and violence surrounding Disabilities, through organising, discourse, and imagination. We aim to connect people across different Disabilities, moving towards another possible world.

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

Gloria Anzaldúa, Foreword to the Second Edition, This bridge called my back: writings by radical women of color, editors, Cherrie Moraga, Gloria Anzaldua, NY: Kitchen Table, Women of Color Press, 1983.

2.

Established in 1978, Rehabus operates the largest fleet of accessible buses in Hong Kong.

3.

Guide to Application for a Grant from the Fund, Arts Development Fund for Persons with Disabilities: https://www.swd.gov.hk/storage/asset/section/337/en/Guide%20to%20Application%20for%20a%20Grant%20from%20the%20Arts%20Fund_EN_6th%20batch.pdf (accessed 17 Jan 2025)

4.

https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/library/crip-zine-issue-01-how-may-i-address-you–01 (accessed 11 Dec 2024)

5.

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice, Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019, p48.

6.

https://www.instagram.com/reel/C9UlPNZAqCC/?igsh=MTN2djEzZHEycnBsYw== (accessed 20 Feb 2025) Translation by the author.

7.

Michael Davidson, Concerto for the Left Hand: Disability and the Defamiliar Body (Corporealities_ Discourses of Disability) (2008, University of Michigan Press), p194.

8.

Translated from Chong Chan Yau autobiography 莊陳有口述,江瓊珠整理,《我看不見,但⋯⋯》,進一步多媒體有限公司,1998,73頁。Translation by the author.

9.

In the Hong Kong context, mutual aid groups refers to non-registered self-help groups for the Disabled or patients with chronic disease and their caregivers. Different from the western understandings of “mutual aid”, many Hong Kong mutual aid groups were founded under the social welfare system or even with funding from the system, to encourage peer support. Reference from Shohub: https://shohub.hksr.org.hk/course/startup4-1/ (accessed 2 Feb 2025)

10.

https://thearcmov.org/history-of-people-first (accessed 2 Feb 2025)

11.

Here is a list for self-help organisations in Hong Kong, which names all groups under “patient”, categorised with all kinds of “illness terms” from medical system: https://shohub.hksr.org.hk/static_page/shosearch (accessed 2 Feb 2025)

12.

From the definition of “Sheltered workshop” on the website of the New Life Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association (NLPRA): “Sheltered workshops provide people in recovery of mental illness and people with disabilities with a working environment specially designed for vocational training through an income-generating work process.” NLPRA was the first Disability organisation that started to introduce sheltered workshops in Hong Kong. While the so-called “income-generating work” only gives a very low salary to Disabled people.

13.

https://theinitium.com/article/20161021-hongkong-carehomescandal (accessed 2 Feb 2025).

14.

http://www.hongkiu.org/issue.htm (accessed 10 Feb 2025)

15.

https://news.mingpao.com/ins/%E6%B8%AF%E8%81%9E/article/20231116/s00001/1700040083263 (accessed 10 Feb 2025)

16.

https://www.hk01.com/article/309348?utm_source=01articlecopy&utm_medium=referral (accessed 10 Feb 2025)

17.

【手語・權】「千手翻譯員」邵日贊 https://www.mpweekly.com/culture/cu0001/%E6%89%8B%E8%AA%9E-%E8%81%BE%E4%BA%BA-%E6%AE%98%E9%9A%9C%E4%BA%BA%E5%A3%AB-22434 (accessed 11 Jan 2025) Translation by the author.

18.

https://www.inmediahk.net/node/1047422 (accessed 10 Jan 2025)

19.

http://www.chosenpower.org/%e9%81%8e%e5%8e%bb%e5%8d%81%e5%b9%b4%e4%b8%8d%e5%96%ae%e6%98%af%e6%99%ba%e9%9a%9c (accessed 11 Jan 2025)

20.

https://www.hk01.com/article/524117?utm_source=01articlecopy&utm_medium=referral (accessed 13 Jan 2025) Translation by the author.

21.

Susan Wendell, Toward a Feminist Theory of Disability, Lennard J. Davis edited, The Disability Studies Reader (second edition) p245.

has a background in literature and cultural studies, and has been engaged in inclusive and community arts work in Hong Kong for over ten years. She has been involved in curating, self-publishing, performance art creation, and research. Currently, she is striving to become a researcher in Disability justice, restarting her learning in Hong Kong Sign Language, and is soon to become a mother.