Climate Post-Script at the Eleventh Hour

Suha Hassan

CATEGORY

The following consists of three interconnected components that provide insights through a geographically grounded temporal perspective. The first component features a series of reflective, rhetorical questions that aren’t explicitly answered by the subsequent sections; instead, all three parts work together to provide insights into the challenges encountered when establishing the first iteration of the AA Climate Cartographies course in Khartoum.

Date: Fri, 13 Sept, 23:00

Site: Stockholm

I write this prelude after clicking on an email sent by a friend that informs me about the looting of artefacts from the National Museum in Khartoum. I was unsure why I was sent this article, as this friend had previously contacted me requesting that I copy-edit the text for the National Museum for the MSc,[1] and update the website to inform people—someone— that things are being looted. Then we could circulate it widely via our Instagram accounts, which at best reaches a few influencers who follow our main account as well as our personal ones. I felt obliged to do something, so I replied to an email from the upcoming meeting for the Board of Directors of the Society of Architectural Historians (SAH) inquiring from one of the board members, and without cc’ing everyone else, if it would be appropriate to share this news with the rest of the Board, as statements of cultural solidarity have been reconsidered in the Society since the genocide in Gaza started. In this, the Society is not dissimilar to many other institutions in “democratic” countries who have decided it is best to ignore the violence abroad and to focus on their own political discord. The email I sent was my attempt to unburden myself by passing it on, like the chain letters that we are told will lead to a curse if we fail to forward them. I think to myself: do I really care about these objects? The reality is I care more about the city that died on April 15, 2023, and will never be the same. Or shall I say on June 3, 2019? Or maybe it was June 30, 1989? Or perhaps January 1, 1956? A city that was destined to die since its independence.

I want to argue that the year 1956 has had the greatest impact on the city. The doomed year of state formation, that would lead to a series of events propelling us into the current state of affairs: an armed conflict. I still find it difficult to use the word war; an armed conflict seems more reasonable, a fight between two sides carrying arms…the definition of a war. I want to use the former term to avoid having to address the societal issues that have led to the war, and to shift the burden to the military: the military alone, with its militia, caused this. Yet I have become more aware recently that the military does not reside in barracks, that a militarised state resides everywhere, in the urban planning ministry, the electricity infrastructure, the dams that generate the power, the water distribution, the heritage site, the traffic police officer, the secret police officer who reveals to you his position to demonstrate his power, the lyrics of a song, the body sway during a dance, the patriarchy, and—more dangerously—the mind. And it is perhaps the latter site, the mind, which is of interest for this issue. I make up a story that the looted objects are now with a Janosik of archaeology, who is keeping them safe in the cold archives of their institute to return them one day, once the wa…armed conflict is over, once the museum can ensure their security. Over a year ago I gave a presentation in a panel on repatriation at Sharjah Art Foundations’ March Meeting.[2] I wanted to share through my presentation how the importance of museum objects retreats in comparison to the loss of land, of spaces we know, and of spaces we connect to. The objects become secondary, because they are part of an implanted memory, whilst the loss of what we know is what is missed. Museum objects are not often part of our daily lives. I aimed to give a critique of the nation state, as I questioned what the difference is between Khartoum and Warsaw in housing in the museum objects from Nubia that belonged to people considered marginal and displaced by nation building projects. I digress…

The mind. When I started to write this prelude, I intended to talk about the colonisation of the mind, and how difficult it is to get rid of it because it is partially our fault, not only the coloniser, but the colonised, whose blame for the coloniser leaves little room for assuming agency, and with it a space of power. I am not in any way absolving the coloniser from their extractive forces, but I think there is a need to be more self-reflective. What does a National Day of Liberation mean? That we have successfully mimicked our coloniser and stepped into their world system? What would a true liberation day look like, one where we are no longer in the shackles our current civilisation imposes? How can we speak about climate change, which I am happy to let you know you will read more about in this text, satisfying the “woke” liberal within you who knows the correct discourses. I digress again. How can we speak – or to quote Greta Thunberg – “dare we speak” on climate change when our current system enforces borders so violent that even those fleeing wars cannot seek refuge? Borders might be the most dangerous human-created catastrophe that will ensure that the world population will be controlled by trapping them within human-made lines, allowing them to be killed. We have seen this from Libya to Syria, to Sudan, to Yemen…to Gaza…the inability to move has killed people. I digress…hopefully for the last time.

The colonised mind. I often reflect on an article written by Mohamed Nabeel in which he emphasises the need to use of the word ihtilal and not istimar for colonisation in Arabic.[3] It is often the second word that is used, istimar, and it is derived from the root ʿmr. One of its meanings is “to revive the land.” There are other forms of the word, such as ʿmār and mʿmār, which are related to architecture.[4] What does it indicate when we ourselves perpetuate through language that it is the coloniser who performs this action of “constructing the land” on our behalf? Language, in all its forms—the textual expression, the audible, the illegible, the visual, the map—can either limit or liberate our imagination. As Walter Mignolo writes, that coloniality is what continues today, expressing that the coloniser remains through the worlds they have constructed over past centuries.[5] A different form of colonisation remains that is perpetuated through more obscure methods, language, in all forms and expressions including maps. Mapping is a world-building exercise, through which we are able to imagine new realities. Today, the collective consciousness is shifting as these hidden structures become exposed through multiple -icides. How can we confront the colonisation of the mind, of our thinking, of our views? That would require confronting ourselves, our belief systems, and much more. How has pedagogy contributed to or been affected by this in the land of the confluence of the Nile River? And what pedagogy of the environment develops under militarised, post-colonial, not yet liberated conditions?

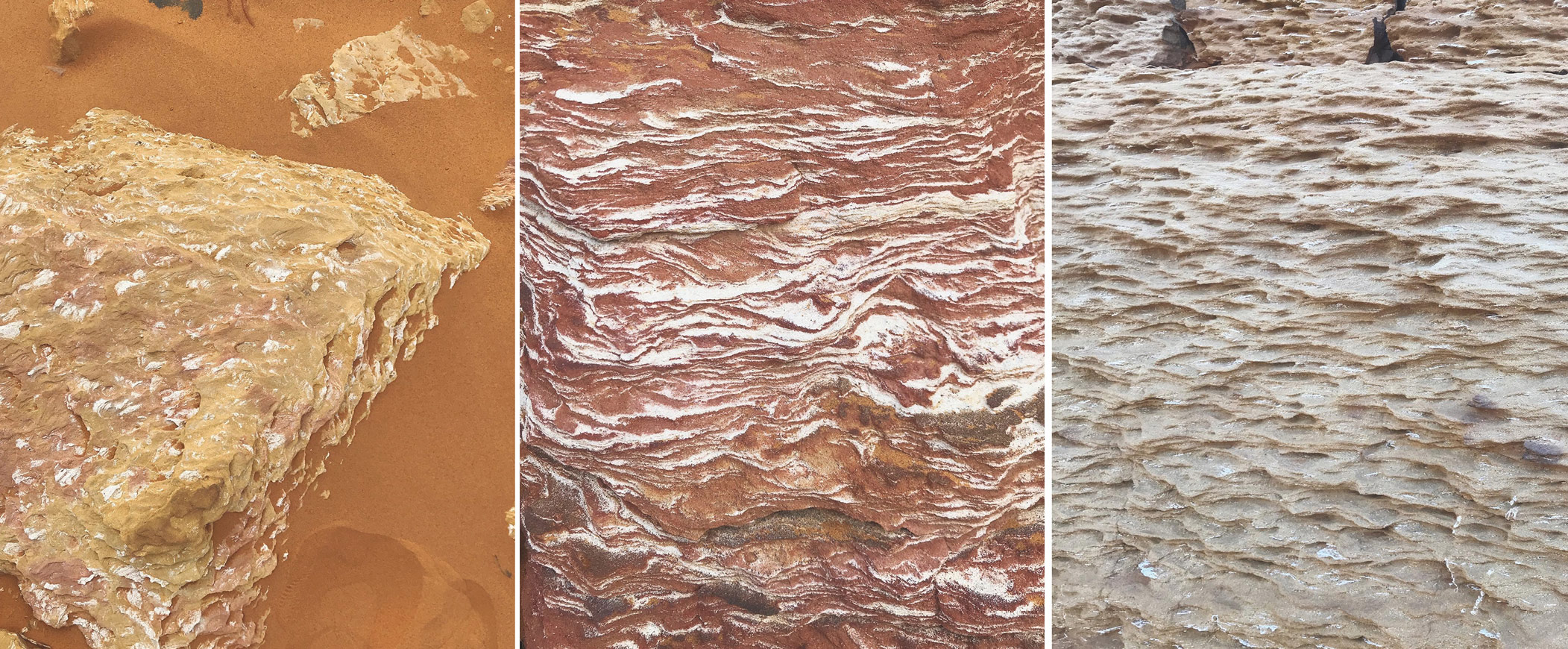

The banks of the Nile, Khartoum, August 2015. Photo by Suha Hasan

Date: Sunday, January 1, 1956

Site: Khartoum

Some answers to these questions require an interrogation of the history of modern education in the country and how it was shaped by coloniality and its intertwinement with the military. A connection that can ominously be made geographically, as the first university’s housing is called the Barracks, once serving the colonial army, today serving as university students’ housing. This coincides with ‘modern education’, used here to describe a rupture from previous education systems in the late 1800s in Sudan, at a national scale that would influence both the education system and political life and social structures. It also encompasses the establishment of the first higher education institute in the country. This shift in education can be considered a shift from systems connected to ideologies and religious practices towards systems that prioritise economic production, which was becoming the new doctrine. Although educational facilities were in the service of the economy, they quickly became the battlefields for their political and religious ideologies of youth arriving from different cities, in addition to spaces for discussions on colonisation and liberation, and conflicting ideas about traditional and modern lifestyles. They would also shape the future of the country as graduating classes entered society; they brought visions of how to guide the country in new directions.[6]

The preceding education systems included now-obsolete education programmes in Christian Nubia, religious Islamic schools that had existed for centuries, secular schools established by the Egyptian authorities in the nineteenth century, and missionary schools.[7] The consolidation of power in the hands of the British administration after the battle of Omdurman led to the introduction of large-scale changes. From that time onwards, education was closely intertwined with the British involvement in the land of the Nile Confluence, its constitutional developments, and its liberation struggles.[8] The new approach to education transformed educational facilities into sites of conflict and power struggles. Some claimed that this was a way for the British to make amends after the battle of Omdurman, while others claimed that education was needed to coordinate with the demands of setting up the government’s civil service, as well as those of the industrial development that was needed for the economy.[9] Elsewhere, education was seen as a means of civilising people and making them less “fanatic,” a word that seemed to be associated with any attempt to escape from British domination.[10] Therefore, modern education was seen as a method of shaping individuals’ characters to adhere to certain morals whilst shaping their skills to become part of the economic production machine and the administration. The expansion of schools during the first half of the century was driven by market demands, an increasing demand for education for girls, and missionary efforts.[11]

During this first period, future landmark educational buildings, such as the Gordon Memorial College and the Kitchener School of Medicine at Khartoum, were established. These would later be united, first as University College Khartoum, then as the University of Khartoum.[12] The inception of the university was to celebrate the fallen General Gordon, who was killed by the Mahdi army—a blow to empire—and as a result also sainted. Furthermore, Gordon Memorial College was also developing a qualified military force and low-ranking government administrators. This coincides with the emergence of new education systems for girls. Unity High School was established as the Coptic Girls School in 1903, becoming the Unity School for Girls in 1928 and then the co-educational Unity School in 1985; similarly, Babikir Badri’s school for girls in Rufaa began in 1907, followed by Al-Ahfad, that would later become the first university for women.[13] The first national educational plan was launched in 1938, but its goals were not reached as the Second World War increased the costs of materials and labour.[14] A second educational plan, known as the Brown Plan, was launched in 1946 and was renegotiated in 1949 to develop separate legislations for North and South Sudan reflecting the continuous marginalisation of the South and a border drawn long before the official separation.[15] At this time, three high schools were established whose alumni’s professional and political careers would influence Sudan’s future: Hantoub, Wadi Sedna, Khor Taqat.[16] The first government after independence used the school system to build consensus amongst a diversified population by sending people from one area to study in a school in another area. After official independence in 1956, further expansions occurred.

Architecture was not only a venue for educational activities but a crucial process through which the maximum benefit of knowledge exchange could be achieved. Early on, conversations about how the space would assist students in learning were common, from choosing the right site for an educational facility to orienting the building to achieve the best lighting and ventilation. To further emphasise this connection, in 1961 UNESCO established the UNESCO School Construction Bureau for Africa in Khartoum (USCBA). The unit was initially tasked to “design buildings for three African countries with different types of tropical climates”.[17] It was directed by an architect who had studied educational methods in the UK.[18]

Educational facilities significantly affected the post-independence condition. Students debated concepts ranging from political and religious ideologies to ideas about colonisation and liberation. As these students graduated and began to shape the future of the country, they brought with them their vision of how to construct a nation that was new and different.[19] The new vision required architects that would construct it and so, appropriately, the Department of Architecture was established in 1957, one year after independence. In fact, prior to that, and coinciding with movements to gain independence, four students were sent by the Ministry of Works headed by Mirghani Hamza, a civil engineer, to study architecture at Leicester University whilst the architecture department was being established at University of Khartoum. Abdullah Hamid, Abdel Moneim Mustafa, Hamed Alkhawad, and Hashem Mohamed Osman would return and work at the Ministry, whilst in Khartoum the Technical Institute started to provide training for architect assistants. The Minister then established the Department of Architecture.

In 1957, the Dean of the School of Engineering addressed thirteen students from the 1955 intake in the School of Engineering informing them about a new field of study, architecture, that they would learn more about from a professor who would arrive shortly from England. Two weeks later, they found themselves listening to a lecture by Alick Potter who explained to them what architecture was and requested volunteers to join the programme. Four students raised their hands: Bolis Saleeb Abdulmalik, Christo Lambrianos, El-Amin Muddather, and Omer Alagra. They had one condition, that they would still receive training in civil engineering. Ever since then architecture studies were closely connected to structural engineering. The building used for the department where they would study was a five-by-five storage unit that was part of the national museum. It was retrofitted with a false ceiling, electricity, two window openings, fans, and seatings for four students. Whilst they continued taking courses with the other engineering students, in this room they consumed Bannister Fletcher’s History of Architecture, the tree, and carried out their studio projects, often sleeping in the room. Two of the architects would later be commissioned to design educational buildings within the University of Khartoum.[20]

The establishment of the Department of Architecture can be seen as part of the desire to fulfil the requirements of the nation-building project. The act “to construct” can be seen echoed in school anthems and all the way across time to the 2018 protests “to build a new.”[21] Yet, as argued earlier, “to construct” has become an action that is constrained by a “tree of architecture,” which grows in one direction, and which does not allow for growth in new directions that would lead to the exploration of new terrains, liberating spaces, different poetics, and a knowledge that can find roots elsewhere. These limitations are clear in the pedagogical approach in the department, which has remained true to the early years of its formation, with the exception perhaps of expanding to include new tools and technologies. Yet the conversations have remained those of a strongly rooted tree.

First batch of architecture students at University of Khartoum: Photo courtesy of Durham Archives

August 2021, December 2021

Site: Zoom

The relationship between the Architectural Association (AA) School, Nubia, and the climate cartographies course has an intriguing background, when reflected upon in retrospect. It is connected to Abdulla Sabbar, who led a short experimentation in architecture education between 1964-1965. He is an alumnus of the University of Khartoum and the AA, who hailed from Ashkit, a border city between the first and second Nile Cataracts that is now submerged by water.[22] He graduated as part of the fourth intake at the University of Khartoum in 1964 and started the architecture programme at the then University of Sudan, that was part of the government’s revolutionary vision at the time. He was sent on a scholarship to study in the AA School’s Tropical Architecture programme and he continued there for another year after the programme and completed a second master’s in urban planning.[23] By the time he went back to Khartoum, the architecture programme he had established was shut down, and the university demoted to a technical college, due to shifts in the balance of political power. Abdulla Sabbar had been to the AA School before, when he carried out his twelve-month apprenticeship at the architect Denys Lasdun’s office in London during his second undergraduate year. He would often attend lectures at the School. The apprenticeship was part of the programme at the University of Khartoum that aimed to expose students to other geographies, so they could learn and bring back with them new skills.

Abdulla Sabbar brought back with him in 1963 two tools that the government which sent him did not expect or predict, and that would cause him a lot of agony as a student. He brought a camera, gifted to him alongside a map from his employer who requested he take photos of Le Corbusier buildings in Europe. Abdulla Sabbar followed the suggested route, took the photographs, annotated them and sent a copy to Denys Lasdun while keeping another copy at his school in Khartoum. The other tool he brought back from London was the revolutionary fervour of the times. According to Abdulla, what shocked him the most were the revolutionary sentiments in the streets of the heart of the Empire. He returned with these sentiments to the capital of the newly forming Sudan and found out that his village Ashkit was about to be submerged. Abdulla Sabbar discovered the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia, and asked to join the campaign, using the loss of his village as his reason. He worked with William Y. Adams’s team and was able to access all the sites undergoing archaeological excavations on the Nile from Aswan in Egypt to Dal in Sudan. He actively documented these trips and his village before it was flooded with the limited film he had, two rolls of film with 36 exposures each. During these trips he would often engage in conversations promoting protests and would actively start to join protests against the construction of the Aswan Dam. This led him to prison, from where he completed his architecture studies and submitted his graduation project. His first project after graduation was housing for the wardens of the prison he was in.

This anecdote provides a close reading of one of many stories from Nubia at the time. The erasure of Nubia has in many ways invented it in the imagination of others. For example, today one of the largest centres for Nubian Studies is in Warsaw, a result of the Polish archaeological expedition that revealed the Faras Cathedral, which highlights the Christian heritage of Nubia.. In fact, there is more information on Nubia in Warsaw today than there is in institutions in Khartoum. Nubia disappears or is at best diluted with the formation of the nation state, while it becomes part of the formation of a nation state in Eastern Europe. Perhaps, then, to study Nubia in the context of Sudan becomes an attempt to reject the nation state project, to rethink independence and to explore spaces that have been marginalised, to attempt to understand new narratives. Yet, as mentioned above, thinking through Nubia would only become more apparent when setting up the course.

Ironically, the Climate Cartographies course started because of the flooding of the Nile in 2019. The increase in flooding resulted in large displacements of people along the riverbanks. It was necessary to understand this problem beyond the limitations of the usual international organisation reports, and this dictated bringing together interdisciplinary expertise that included architects, artists, community groups, scientists, archaeologists, bio-archaeologists, and so on. The programme, that was initially intended to be set up as a PhD programme at an institution in London or Stockholm, was afforded the opportunity to be hosted at the AA School. Choosing a heritage site became a deliberate choice, as it became an avatar for the people who would allow these conversations without subjugating those affected by the floods. Furthermore, to protect a heritage site often seems to require a more urgent action, as opposed to protecting people. As a result, these sites are often very well researched and documented, and present a lot of data. Although heritage sites are political, and come about as a result of politics, they are also a climate archive that charts the environmental changes through the deep historical investigation that goes on around them.

Cartography was used in the course as the language of expression, because of the agency it affords the students to engage in world building. Map making is the production of a system of codes that enable an understanding and a communication of a far larger and more complex reality. This idea of mapping out new historical narratives draws from James Corner’s ideas, put forth in his chapter, The Agency of Mapping.[24] He discusses the importance of producing new maps, and not tracings or replicas of other maps, as mapping can be a form of producing new and unseen realities, whether it involves drawing relations on a physical map or drawing relations through references to history and historical accounts. Deleuze Gilles and Félix Guattari see that all maps are a production of the natural process that takes place when different agents encounter an environment; within this interaction, new maps are continuously being produced.[25] As architects, we can relate to this: not only do we read maps, but we are continuously producing them to shift the paradigm of the viewer. Muhammad al-Idrisi’s map of the world continues to beautifully depict how a drawing can centre and decentre.[26] More contemporary projects, such as the Million Dollar Blocks at Colombia Centre for Spatial Research and a People’s Guide to Los Angeles visualise inverted readings of spaces in the city, whilst Forensic Architecture’s A Cartography of Genocide (2024) is an examples of how mapping can afford us new ways to communicate counter narratives.[27]

From the barracks of the University of Khartoum, to the landscapes of Nubia,, the course explored new ways of engagement, understanding the limits imposed by the context, yet attempting to find opportunities from this same context to discover new ways of thinking and imagining that could break away from the repetitive readings of the context that have often limited our imaginations.[28]

Abdulla Sabbar’s personal archive documenting his village before it was flooded, Dubai, 2023. Photo by Suha Hasan

This has been commissioned and uniquely presented for Urgent Pedagogies, published as part of Urgent Pedagogies Issue #11: Climate Cartographies.

Climate Cartographies was partly supported by the British Institute of Eastern Africa, the British Academy, and the architecture firm Iskan.

1.

Modern Sudan Collective. https://www.modern-sudan.com/

2.

Sharjah Art Foundation, ‘Reparations and Repatriation: New Developments and Discourses’, Esra Akcan, Manthia Diawara , Suha Hasan, Salamishah Tillet, and Salah M. Hassan (Moderator). March Meeting 2023, 12 March 2023. https://www.v1.sharjahart.org/sharjah-art-foundation/events/march-meeting-2023-reparations-and-repatriation-new-developments-and-discou

3.

Mohamed Nabeel alerts us to the importance of using another word in Arabic in ql iḥtlāl! Lā tql istʿār! [Say Occupy! And don’t say ‘to construct’!], Al Jazeera, May 24, 2017, accessed November 1, 2024, www.aljazeera.net/blogs/2017/5/24/قل-احتلال-ولا-تقل-استعمار

4.

Suha Hasan, Epilogue, in ‘Spaces of Writing History in the Postcolonial City: Edits, Erasures, Inscriptions’, PhD diss., KTH Royal Institute of Technology, 2022, 280.

5.

Walter D. Mignolo. ‘Delinking: The Rhetoric of Modernity, the Logic of Coloniality and the Grammar of De-coloniality’. Cultural Studies 21, no. 2–3 (2007): 449–514.

6.

Willow Berridge. “Colonial education and the shaping of Islamism in Sudan, 1946–1956.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 46, no. 4 (2019): 583-601.

7.

Lilian Sanderson. “A survey of material available for the study of educational development in the modern Sudan, 1900-1963.” Sudan Notes and Records 44 (1963): 69-81; Yusuf Fadl Hasan. “Interaction between traditional and Western education in the Sudan: an attempt towards a synthesis.” Conflict and harmony in education in Tropical Africa (2021): 116-133; Iris Seri-Hersch. “Education in colonial Sudan, 1900–1957.” Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of African History (2017); Intisar Soghayroun El Zein. “The Nilotic Sudan.” The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Archaeology (2020): 402-404; Sudan [Condominium, 1899-1955], Education Department: Annual report of the Education Department, 1935-1938 (8v) (Khartoum, [1935-1938]), Sudan Durham Archive.

8.

Mamoun Sinada. “Constitutional development in the Sudan contemporary with the evolution of the University of Khartoum.” Sudan Notes and Records 61 (1980): 77-88.

9.

James Currie. “The Educational Experiment in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1900-33. Part I.” Journal of the Royal African Society 33, no. 133 (1934): 368-369.

10.

James Currie. “The educational experiment in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1900-33. Part II.” Journal of the Royal African Society 34, no. 134 (1935): 41-59; Samuel Thomas Adrian Grinsell. “Urbanism, environment and the building of the Anglo-Egyptian Nile valley, 1880s-1920s.” PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, 2020, 54.

11.

Lilian Sanderson. “A survey of material available for the study of educational development in the modern Sudan, 1900-1963.” Sudan Notes and Records 44 (1963): 69-81; Yusuf Fadl Hasan. “Interaction between traditional and Western education in the Sudan: an attempt towards a synthesis.” Conflict and harmony in education in Tropical Africa (2021): 116-133.

12.

Ashley Jackson. “Gordon Memorial College, Khartoum,” in Buildings of Empire. Oxford University Press, USA, 2013, 194-219.

13.

Heather J Sharkey. “Christians among Muslims: the church missionary society in the Northern Sudan.” The Journal of African History 43, no. 1 (2002): 51-75; Amna E. Badri. “Educating African women for change.” Ahfad Journal 18, no. 1 (2001): 24-35; Lilian Sanderson. “The Development of Girls’ Education In The Northern Sudan, 1898‐1960.” Paedagogica historica 8, no. 1-2 (1968): 120-152.

14.

Abuelgasim A. Salih. “A study of technical teacher training in the Sudan and in England and Wales.” PhD diss., Loughborough University, 1984.

15.

Abuelgasim A. Salih. “A study of technical teacher training in the Sudan and in England and Wales.” PhD diss., Loughborough University, 1984.

16.

Salaheldin Farah Bakhiet and Huda Mohamed. “Gifted education in Sudan: Reviews from a learning-resource perspective.” Cogent Education 9, no. 1 (2022).

17.

Kamal El Jack. “Regional school building centre for Africa, Khartoum.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 6, no. 3 (1968): 417-419.

Gerd Biermann, November 1, UNESCO School Construction Bureau for Africa (USCBA), Khartoum, Sudan, Report on Activities and Results and Conclusions from 1961 – June 2, 1963, UNESCO, December 26, 1963.

18.

L. Garcia del Solar. Report on the Activities of UNESCO’s Regional Educational Building Institute for Africa (REBIA). UNESCO, August 1971: 7.

19.

Willow Berridge. “Colonial education and the shaping of Islamism in Sudan, 1946–1956.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 46, no. 4 (2019): 583-60.

20.

El-Amin Muddather, interview on Zoom, August 11, 2024; Bolis Saleeb Abdulmalik, interview on Zoom, February 25, 2024.

21.

‘Building a new’, chant from the 2018 protests in Khartoum; ‘we are building’, Unity School Anthem.

22.

Abdulla Sabbar shared his story during multiple interviews carried out between 2022-2024.

23.

In recent years there have been many conversations through publications and exhibitions regarding the impact of the AA Tropical Arhitecture program, see Ola Uduku, “Modernist architecture and ‘the tropical’in West Africa: The tropical architecture movement in West Africa, 1948–1970”, Habitat international 30, no. 3 (2006): 396-411; Bushra Mohamed, Christopher Turner, and Nana Biamah-Ofosu (curators), 2023, Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa exhibition, Venice Architecture Biennale, V&A; Albert Brenchat (curator), 2023, As Hardly Found in the Art of Tropical Architecture exhibition, AA School.

24.

James Corner, ‘The Agency of Mapping: Speculation, Intervention and Critique’, in Mappings (Critical Views), ed. Denis Cosgrove, (Reaktion Books, 1999), 213– 252.

25.

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. ‘Introduction: rhizome’, in A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987, 3-25.

26.

Muhammad al-Idrisi. Nuzhat al-mushtāq fī ikhtirāq al-āfāq, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, 1553.

27.

See Forensic Architecture, A Cartography of Genocide, 2024, https://gaza.forensic-architecture.org/database; Laura Kurgan, ‘Million-Dollar Blocks’, in Close Up at a Distance: Mapping, Technology, and Politics, MIT Press, 2013, pp.187-204; Laura Pulido, Laura R. Barraclough, and Wendy Cheng. A people’s guide to Los Angeles. Univ of California Press, 2012.

28.

I want to express my gratitude to Hanaa Motasim M. Ali, Matthew Ashton, Sadaf Tabatabaei, Stany Babu and Tatiana Pinto for their close reading of the text, as well as their valuable feedback and insightful questions. Additionally, I would like to express my appreciation to Malý Berlín in Trnava, Slovakia, for granting me a residency in a creative environment where this text started to develop.

is an architect and founder of ASH, an architecture practice based in Stockholm, Sweden, which provides design and consultation services for heritage and cultural management. She has lectured and taught in universities in Bahrain, Egypt, Singapore, Slovakia, Sweden, Sudan, and the UK. She trained as a journalist while studying architecture. Suha founded Mawane, a platform for urban research based in Bahrain and is a founding member of the MSc [Modern Sudan collective]. Both platforms enable researching and sharing the outcomes through public art exhibitions, talks, and workshops.

Architectural Association School of Architecture Visiting School Climate Cartographies: https://climatecartographies.aaschool.ac.uk/

Modern Sudan Collective. https://www.modern-sudan.com/