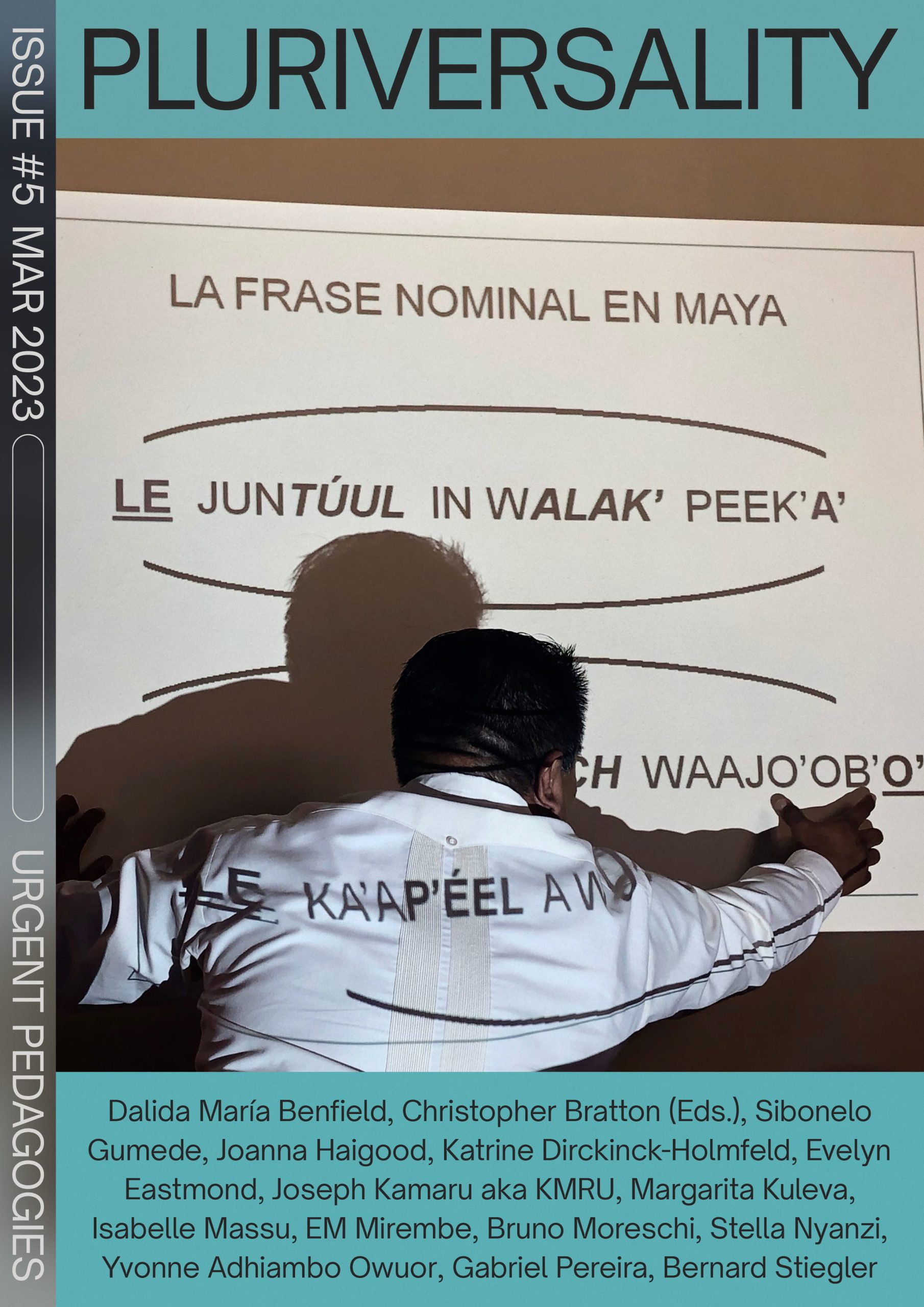

Temporary Stored

Joseph Kamaru aka KMRU

CATEGORY

Joseph Kamaru aka KMRU questions the colonial archive upon which European/Occidental thinking, schooling, and listening rely. Kamaru’s project, Temporary Stored, liberates the sonic beings of ancestors.

In his research, he situates listening practices, and in turn, the production of sound, as having the potential to revitalize subjectivities, against the objectification and racialization enacted by sonic colonialities. Kamaru’s liberation of sounds from the colonial archive includes first, accessing them, which is no small feat given their institutional enclosure; then, a close listening to them; and finally, re-mixing them with field recordings and synthesizers. This re-encantation honors his, and our collective, ancestralities.

Listening, too, is constructed around a Western scope of thought, narrowing the extent of what different listenings could produce and posit. Approaching a more pluralistic listening, I propose a Black listening approach, an auditory imagining through Blackness. Listening that seeks to engage with contemporary and socio-political cries through Black sonic thought, which a Black listening perspective could proffer a deeper view and dispositions of Other listening practices. White mishearing and auditory imaginings of Blackness have often been sanctioned, being a matter of life and death in most Black societies. Recent events are halting the usual silences surrounding the violent consequences of the racialisation of both sounds and listening, decolonizing listening practices, and exerting freedom to sound, safety, and diversity in everyday listening practices.

Blackness in sound and listening is equated with dangerous noises, outsized aggression, and threatening strengths. Although these sounds of resistance are heard or unheard, they have histories. There is a defect in the media, which represents that these circumstances and occurrences are not related to race or the identity of the people, and the majority wants to omit this conversation about sound in conjunction with the discourse of race. A proposition by Stoever (2016), however, on the sonic color line posits that listening operates as an organ in racial discernment, categorization, and resistance in the shadow of cultural dominance [1]. While race is thought of mostly in an ocular-centric dimension, sound and listening have served a greater part in producing the apprehension, oppression, and confrontation rendered in this discourse. Attitudes towards skin colour and visible phenotype differences, such as skin and hair colour and texture, categorize the power differentials resulting from an ideological, racialized visual gaze. Nonetheless, listening also operates in the same scope of racial discernment, categorization, and resistance, in the shadow of visual cultural dominance.

The role of the listener and the speaker is what results in these frictions of discrimination. Therefore, listening practices of modern aurality merge as a crucial activity of analytical and theoretical inquiry. Questions of who is listening, being listened to, and where, or with whom, one listens are critical to reflect upon while considering a Black listening perspective. Listening is often related to the spaces being heard or listened to. Hence, in this concept of Black listening, a posit for the notion of habitus is crucial. Pierre Bourdieu proposes the notion of habitus and asserts that individuals internalize practices, thoughts, perceptions, expressions, and actions due to historically, socially, and politically conditioned principles and processes accumulated over time. The social conditions in which the habitus are generated are constituted by the social conditions which are implemented.

Until now, it is still evident in the 21st century that an underlying unequal distribution of social power makes voices adhere to the binaries. The role of who is obliged to ask a question is an important element in the politics of listening to one another; therefore, one has to consider the mutuality of both speaking and listening, showing a willingness and to take seriously what the other has to say in order to work together and understand each other in the societal level, thus risking one’s differences and conflicts. This form of participation has a transformational dimension, as Salome Voegelin puts it on listening fragments: an ethic of transformation, a generative possibility. Through listening to the oppressed, there’s a potential possible to understand that there is an inequality listening gap and that the new modes of listening or speaking posited in current listening discourses are not covering the entire scope of the study, hence a deep reflection of what these different modes of listening should be filtered upon considering a larger scope of the sound and listening community [2].

African countries, diasporas, and Other geographies connected to the continent have been objectified by the West, particularly their cultural heritages. Statues, artifacts, instruments, sounds, and other tools have been taken from their natural surroundings, often by force and in the context of colonial violence. The objectification of Other humans as tools, resources, utensils, and labours are enabled by colonialism and racism. Museums and other institutions still harbour many of these objects from the Non-West. This objectification of rituals, spiritual beings, historical carriers, and cultural entities is in line with the dehumanization, othering, and Objectification of humans from the non-West [3]. It has been recently realized that institutions are enabling and constructing Otherness through the improper, unethical storing and archiving of these objects and histories. Most of this harbouring has only been legitimate to tangible heritage. The intangible, ephemeral, hasn’t been mentioned in the extortion, exportation, and looting of heritages. Museums and institutions have reduced the Other by temporarily storing histories framed by white thought.

Archives have always been framed in a guise that promotes a Western perspective of representations of the Other, a modernity in which the institutions and museums frame these archives and collections. These ways of representing the artifacts, either tangible or intangible, problematise the mode in which the knowledge or histories of the peoples are communicated. For example, most African traditions are passed across through apprenticeship and other oral traditions, which are usually put out of context when reconfigured in a Eurocentric dimension. Written sources in the West are deemed ontologically concrete and immune to individual distortion, whereas oral sources seem nebulous and subjectively constituted [4]. In line with Agawu’s thoughts, this connects with the normalization the West has tried to form on the Other. In relation to the oral archives, it also seems that there is a certain contextual fixity of the unknown. Archives of Africans are written, and are reflections of European bias and orderings of knowledge; therefore, descriptions of the archived objects and artifacts are mostly misinterpreted due to the lack of connection with the Object. The subjectivity of the so-called objects is usually neglected.

The objectificaton of these artifacts could be juxtaposed with the Othering already discussed. From an archival point of view, one must understand that these objects possess subjectivity, agency, and consciousness. As Ndikung mentions in his book, Those Who Are Dead Are Not Ever Gone, the Objects have feelings and desires; they possess agency and wield power over individuals and societies; this is why they are offered sacrifices and prayed to and appeased in various ways. They are not representations of ancestors but, indeed, ancestors themselves [5]. There should be an understanding that the difference of cultures does not disrupt the norms that each of them has individually, but the difference reifies a cultural thrive. Western museums, therefore, have to stop the objecthood of the artifacts and repatriate them to their subjecthood.

*

An archival-object listening thus could posit epistemic pluralities and transformative practice in which museums and institutions could return these ‘objects’ back to their places of origin. Although this process does take much effort, there needs to be an unschooling of the Western epistemologies and representations of the archives, as there is still ongoing internal colonialism. The colonial structures still dominate and affect Black, indigenous and people of color, as well as instituting a universal knowledge and objecthood on them.

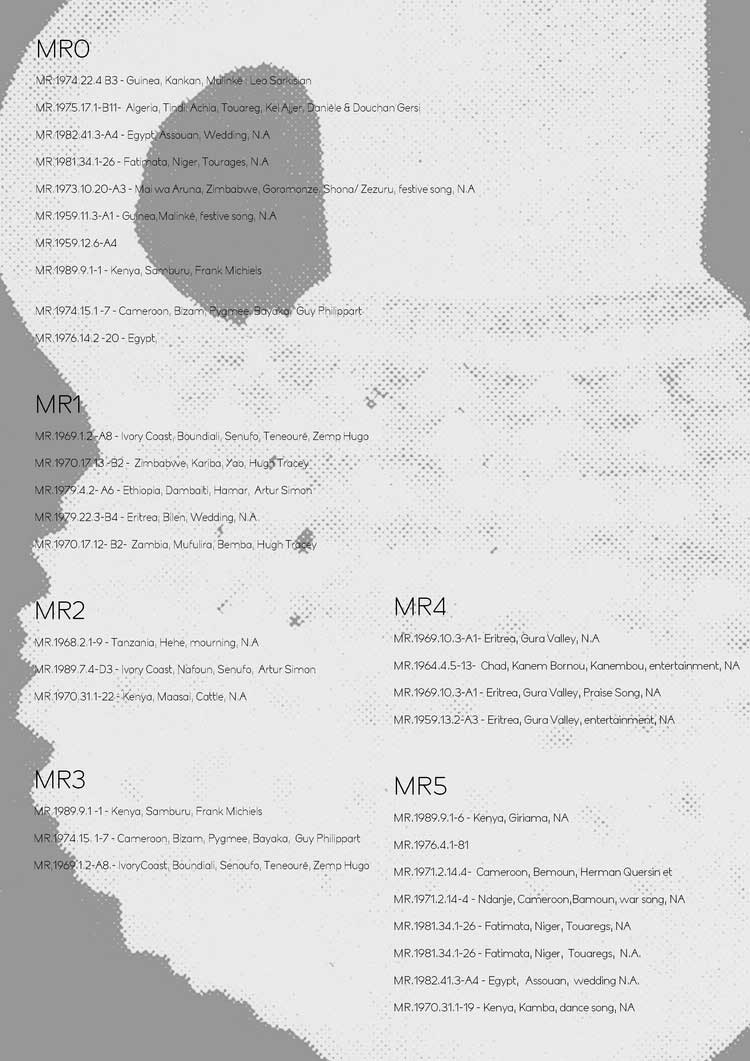

“MR0,” Temporary Stored, KMRU, 2022. Cover art courtesy Joe Gilmore

An ongoing extraction of cultural property has occurred in colonies outside Europe, leading to the objectification of artifacts, humans, tools, sounds, instruments amongst other materials. This harbouring of objects in museums and institutions is unethical and problematic as the so-called ‘objects’ are not regarded as objects in an African context. These are historical carriers, spiritual beings, and cultural entities that have been passed on over generations and are meant to be learned from and act as reflections of past and future histories, although these histories are not accessible to whom they belong to impetus imagined histories of the past. The occident has accumulated most of these archives and continuously reproduces a colonial pattern in this discourse.

Temporary Stored is a repatriation project which questions the significance of sound archives in museums. Using selected sounds from an archive from the Sound Archive of Royal Museum of Central Africa, six pieces are developed re-contextualizing what the archived sounds inform of the cultural heritage of countries in East and Central Africa. The tracks focus on narratives throughout different sounds from the archive, field recordings, and synthesizers, reconfiguring ways of thinking sonically through recorded past and (futures).

Temporary Stored, KMRU, cover art. Courtesy Joe Gilmore

Agawu, Kofi. (2003). Representing African Music: Postcolonial Notes, Queries, Positions (1st ed.). New York and London: Routledge.

Cusicanqui, Silvia Rivera. (2020). Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: On Decolonising Practices and Discourses. Cambridge, UK & Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Eidsheim, Nina Sun. (2019). The Race of Sound: Listening, Timbre, and Vocality in African American Music. Durham: Duke University Press,.

Fanon, Frantz. (1952). Black Skin, White Masks. New York: Grove Press.

Fanon, Frantz. (1988). Toward the African Revolution: Political Essays. New York: Grove Press.

Glissant, Édouard. (1997). Poetics of Relation. Trans. Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Hall, Stuart. (1997/2013). “The Spectacle of the ‘Other’.” In Representation: Cultural

Representations and Signifying Practices. Hall, Stuart, Evans, Jessica, and Nixon, Sean, Eds. London: Sage Publications.

Kanngieser, A.M. (2014.) “Toward a careful listening.” In Nanopolitics Handbook, The Nanopolitics Group, Ed. London: Minor Compositions.

Kanngieser, A.M. (2023) “Sonic Colonialities: Listening, dispossession, and the (re)making of Anglo-European nature.” In Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 08 February 2023. Access at https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12602

Lorde, Audre. (2017). Your Silence Will Not Protect You. London: Silver Press.

Levinas, Emmanuel. (2005). Humanism of the Other. Trans. Nidra Poller. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Mambrol, Nasrullah. (2017). “Alterity in Post-Colonialism.” In Literary Theory and Criticism. Access at https://literariness.org/2017/09/26/alterity-in-post-colonialism/

Ndikung, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng. (2018). Those Who Are Dead Are Not Ever Gone. London: AB Pamphlet Series, Archive Books.

da Silva, Denise Ferreira. (2016). On Difference Without Separability.

Stoever, Jennifer Lynn. (2016). The Sonic Color Line: Race and the Politics of Listening. New York: New York University Press.

Treanor, Brian. (2006). Aspects of Alterity: Levinas, Marcel, and the Contemporary Debate. New York: Fordham University Press.

Voegelin, Salomé. (2018). The Political Possibility of Sound: Fragments of Listening. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Parts I and II excerpted from Joseph Kamaru, The Black Other: Alterity, Sound, and Listening Practices, previously unpublished essay.

Temporary Stored is part of Urgent Pedagogies Issue#5: Pluraversality

1.

Stoever, Jennifer Lynn, The Sonic Color Line: Race and the Politics of Listening.

2.

Voegelin, Salomé. The Political Possibility of Sound: Fragments of Listening.

3.

Ndikung, Bonaventure, Those Who Are Dead Are Not Ever Gone, “Act I-V.”

4.

Agawu, Kofi, Representing African Music: Postcolonial Notes, Queries, Positions, 75.

5.

Ndikung, Bonaventure, Those Who Are Dead Are Not Ever Gone, “Act I-V.”

is a Nairobi-born, Berlin-based sound artist whose work is grounded on the discourses of field recording, noise, and sound art. His work posits expanded listening cultures of sonic thought and sound practices; propositions to consider and reflect on auditory cultures beyond the norms through compositions, installations, and performances. He has earned international acclaim for his ‘ambient’ recordings, including his album Peel, released on Editions Mego, sweeping 2020 end year lists from Pitchfork, RA, DJ Mag, Bandcamp to Boomkat, and many more. He has also earned international acclaim for his performances in far-flung locales as well as his most recent release, Temporary Stored. KMRU presents a monthly show on Internet Public Radio, guests on NTS and Rinse FM, organizes workshops for the Nairobi Ableton User group, is a core member of Black Bandcamp. He was a CAD+SR Research Fellow, 2020-2022.

Temporary Stored, KMRU, released July 2022: https://kmru.bandcamp.com/album/temporary-stored

KMRU website: https://kmru.info/

KMRU on bandcamp: https://kmru.bandcamp.com/

CTM 2023: “The Time for Denial is Over,” with Joseph Kamaru (KMRU), Ketan Bhatti, Pamela Owusu-Brenyah, Elia Rediger, Fabrizio Cassol, Kojak Kossakamwe, Patrick Mudekereza, Feb. 4, 2023. Access at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hTI5rRQotdc