To my students: On open processes, social imaginary and praxis

Katya Sander

CATEGORY

“It is often said that ‘imagination knows no limits.’ Well, I disagree. Imagination has limits indeed. There are boundaries to what we can imagine, since our fantasies are always connected to our experiences, whether psychologically or professionally. Thus, these limits are much closer than we would like to admit.”

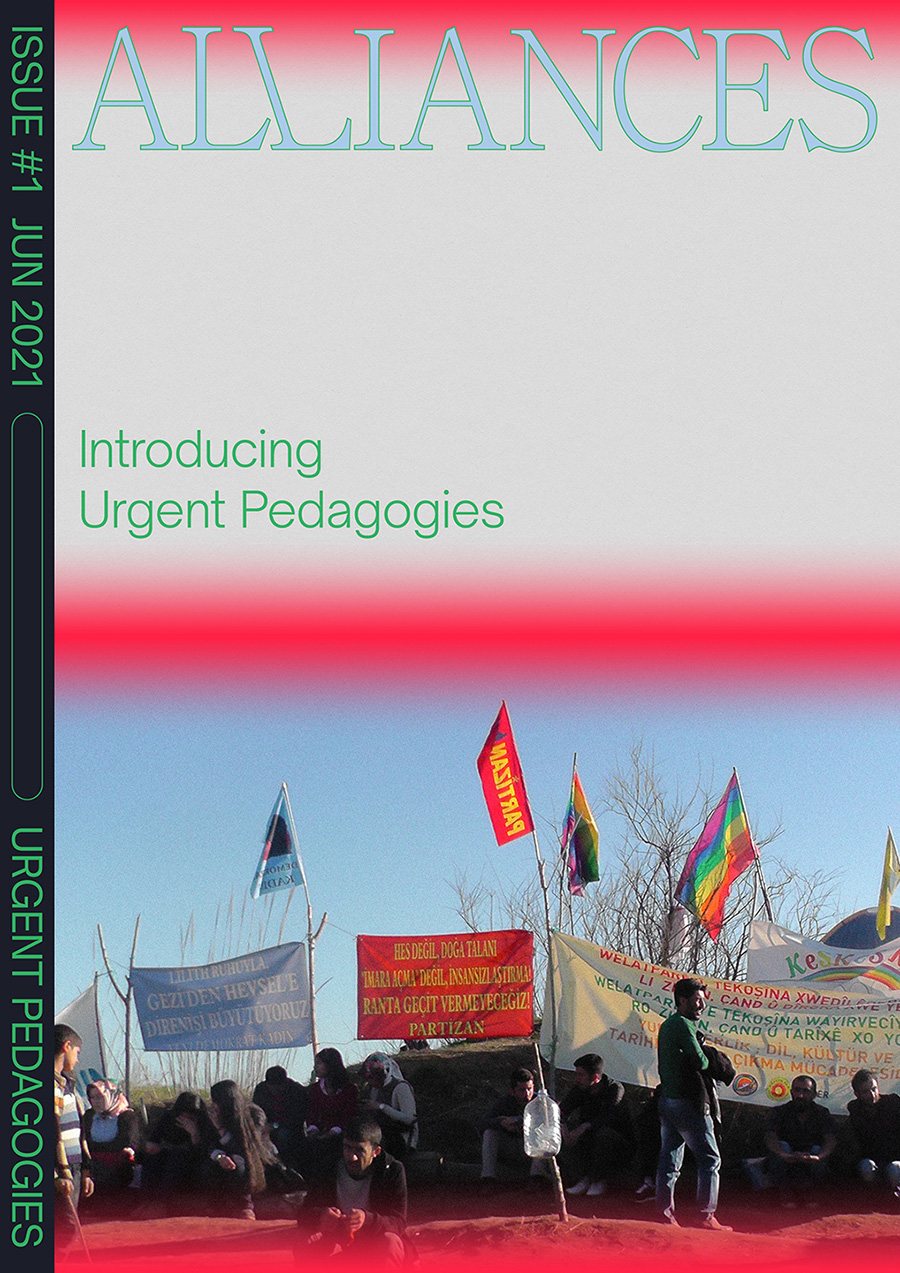

Workshop with Nordlands Kunst og Filmskole, Lofoten, Norway. Photo: courtesy of Nordlands Kunst og Filmskole

If we investigate the greatest discoveries, inventions, or works of art and science, and the contexts they derived from, we soon understand that most so-called ‘new’ ideas appear very closely related to something that was right next to them. It is only when inventions and innovations travel outside of their immediate contexts and discourses that these ideas might suddenly seem so different and so radically new. It is in these instances that we – often too liberally – bandy around the highly ideological designation of the genius to describe our incomprehension of how someone came up with this, and our amazement at their ability to even imagine it, let alone articulate and produce it! However, most artists, researchers and scientists will tell you a different story: When we try to push our imagination, what we mostly do is to mix and re-combine already known concepts, questions, and circumstances to arrive at new relationships and figures: We ask well-known questions in new contexts, or we insert logics from other disciplines into a specific framework, for example. We repeat, re-make and re-model. We use what is around us and what we already know, to find ways towards imagining something else.

This might be quite obvious, especially for artists, scientists. We use what we already know, and we push and twist, investigate, experiment, mix, challenge, shift, and use our intuition and experience from there until we reach a slightly different place. From here, perhaps something else can be known and articulated than before. Or perhaps something similar can be known again, anew, in a different form, allowing this knowledge to operate in a different way. We set out in this activity without knowing exactly where we are going to end – since the very point is that we cannot ourselves imagine it clearly from the beginning either. In other words, we begin our work without a clear goal or result in view. Perhaps with a hunch, an idea or a vision, but never with a clear picture of what lies ahead, and what may be the final results. We may have a direction, but no destination or even destiny.

Let us call this an open process: entering into an explorative process with tactics and strategies for working, with the experience and knowledge of materials, drawing upon previous experiments, but without an explicit end in view.

One of the core competences of artists is the ability to work with open processes – being able to enter into, uphold and navigate a working-process without knowing beforehand precisely what the results might be. Some artists even excel in being able to keep this openness as long as possible – and still be able to end with something we can recognise, but also understand as ‘new’. This kind of work is not exclusive to artists. Many scientific researchers understand this, and for example farmers or traditional craftsmen with a high level of local and material knowledge have historically understood their work in similar terms: To operate through customs, rules, skills and tools, but informed by lived experience, as well as by the resistance and collaboration of materials themselves. This, I would argue, has historically been as formative when reaching new outcomes as any pre-planned result, often perhaps even more decisive.

Insisting on the importance of imagining how things could be otherwise, and maintaining an open process of futurity is becoming ever more rare in most lines of work today. We live in times permeated by a logic through which ‘work’ is defined and validated by quantifying it; measuring for example productivity and time-management efficiency. What is regarded as a valuable work-process nowadays is mainly one aimed at not ’wasting’ resources – especially time – by working without knowing exactly what the goal is and how to define it, and therefore without being able to plan precisely how to best reach it. We live in the paradigm of quantification, in which quantitative information – i.e. definable units from where processes and results can be measured – has become the dominant form of information used for coordination, evaluation, and indeed validation. However, the open process as that which does not prescribe its result, cannot even enter into calculation, as what is calculated are the means according to desired ends, i.e. productivity. We can thus ask how the logic of quantification can produce something new or unforeseen, unless as in the sense of failure and mistake in an act of counting or calculating?

The implementation of numeric technologies in society at large, but also indeed the educational structures, standardization procedures, bureaucratic management, and political decision-making are based on the logic of quantification, and the open process is a luxury for the few and privileged, or a hobby for those who have spare time.[1] Open processes still exist, of course, but since they tend to be less measurable, they are also less recognized, formalized, and therefore less validated.[2] Most of us are paid only for the work that can be measured. Not only researchers, designers and artists will recognize the tendency that central parts of their work are becoming invisible and thus unpayable, domestic and care-workers have known this for a long time, since their ’product’ is something as ambiguous, un-measurable and un-quantifiable as the caring and servicing of others.

In our current political context there is almost no political imaginary outside the quantifiable. This makes art and its institutions fragile, and difficult to defend politically. At the same time, though, it is exactly this quality that shows us that it is an area perhaps much more potentially valuable than ever before, since the ability to imagine something else, has to come from somewhere. It will not suddenly pop up, out of nowhere. It has to “be around”; it has to live in places and pockets where it is considered ’real’ and valuable, insisted on, nurtured, practiced and thus maintained.

As artists, our work is about finding and understanding what the goal could be, rather than knowing it beforehand. This is what makes artistic practices potentially important. But this is also what keeps our profession under constant threat. Exhibition as well as educational institutions in the age of benchmarking and documented efficiency need to constantly and at an ever more detailed level be able to define in precise units what they do; units that can be counted and compared. How many spectators, how many students, how many years, how many study-points, how many courses, how many hours tutoring, how many opening hours, etc. The paradigm of quantification makes it difficult to argue value outside of parameters of measurability, and those who do it, appear easy to dismiss. Structurally, it makes art institutions seem ‘weak’ and easy to argue against; easy to cut back. They make soft and easy targets for politicians eager to play “strong men”.

However, what may seem as a weakness for an institution, might actually also be a central requirement, in that it does not insist too hard on its boundaries – its discipline – and can therefore possibly be negotiated and changed: Something else can be suggested from here. It is a fine balance – to be able to rest on an institutional weakness produced by a paradigm that cannot recognise its core values, yet to keep existing so that this weakness can exactly unfold as potential; a potential for a framework where other worlds can be imagined. How to negotiate this balance?

Imagination does not exist by itself, isolated, from individual to individual, in smaller or larger doses. Rather, it exists in close relationship to our surrounding life-worlds, and what can be thought and dreamt up in these. Imagination is contextual. Imagination is produced and maintained by interaction with people and things around us; it thrives on what we experience others being able to imagine, and on what we are able to communicate as imaginable to each other. Imagination is collective and social: Only through imagining together with others, can we push our capacity to imagine. “That which seems possible to imagine” in a given context, could also be called the imaginary.[3]

The French-Greek philosopher Cornelius Castoriadis defines the imaginary as the capacity humans have to create other forms of individual and social existence. Furthermore, Castoriadis suggests to understand social imaginary as the set of values by which our community or society operates: institutions, laws, symbols – all the instances through which people in a given community imagine their social whole; its realities and possibilities. In Castoriadis’ thinking, institutions are central to the notion of social imaginary, since they mediate rules – or systems and patterns – by which we live; by which we organise and thus transcend being mere individuals. For Castoriadis, ‘the central imaginary significations of a society … are the laces which tie a society together and the forms which define what, for a given society, is “real”‘.[4]

Let us look at a few examples of such institutions: The very idea of representative democracy involves a certain imaginary – and though we today often credit ancient Greek culture for the idea of ‘democracy’, most people in the feudal systems up until the 17th and 18th century would not have considered it possible. However, today, our society has a wide net of institutions and systems for upholding the way in which we choose to be ruled. Likewise, the idea of ’law’ involves the imaginary that most people adhere to (or they will be punished), in order for it to function. We see a number of central institutions in place and central to our society: not only laws being decided through formalised processes, and written into important texts, but also buildings such as courthouses, police stations, or prisons, all with very specific and explicit rules for behaviour. But also something as mundane as parenthood could be seen as an institution, teaching children what kinds of actions are allowed, and which ones are not socially acceptable. The children of course have to trust their parents that they are right. Our trust is central for maintaining institutions and the rules and patterns they project onto us. Another example often used is our monetary system: It relies on our trust that money will not lose its value (too soon). National banks, numbered notes, signatures and images of kings and queens, great buildings or important landscapes, along with very regulated ways in which such notes and coins are to shift hands, is what makes up our monetary system and at the same time our trust in it. The moment we lose trust, it risks collapse.[5] Social imaginaries are tied to the institutions manifesting in them; institutions establishing rules and patterns of behaviour, grounding certain ideas of what the social is, of what society is, of what value is – what we believe and trust it is – and what can thus be understood as real and as possible within this society.

The notion ’the social’ covers an all-encompassing web of relations, connecting or assembling people, things and ideas at large into that which we regard as society. Within the social, different collectives might appear, interweave, compete or co-habit. “A collective” can be thought of in the lines a collection; a number of individuals acting or working together by choice, because they have something in common. The mere choice to act collectively might be what they share, but more often specific relations or situations are shared by people choosing to act or work together. For example, the simple choice of not eating meat any longer, could be interpreted as a ’collective action’: a number of people choose to do this, deliberately, in order to change a specific situation or relation, and to show others that it is possible. It becomes part of the social imaginary.

The social imaginary consists of shared ideas of what is ’real’ and thus what is possible, and it exists between people whose imaginaries are bound up to those ideas.It is obvious that the notion of the social imaginary is linked to ways of life – and thus to politics: How can we live, why, or why not? Castoriadis suggests the notion of autonomy in relation to politics. ‘Autonomy’ in a political sense describes the ability to recognise and analyse social imaginaries, and to develop and suggest changes. In other words, to deliberately and specifically act in order to change the existing social imaginary. For Castoriadis, political autonomy signifies the ability to think and act politically in relation to the social imaginary one is part of; to want to change relationships to and in the world, and to be able to mediate and thus share and spread dreams of other ways of existing.

For us, perhaps the notion of artistic autonomy comes to mind, and it is perhaps not unrelated: the right or ability to suggest whatever one would like to, unhindered by social rules for how to behave; according to what patterns. However, while the notion of artistic autonomy stems from a time when artists sought to free themselves from the duty to service the church and the state, it has also played a role in forming the myth of the free (male) ‘genius’ individual, acting heroically and on his own. Instead, to use the notion of autonomy in Castoriadis, makes us understand that it involves a collective endeavour, to deliberately wish for changes, and to join others with similar wishes in order to help each other develop and make visible other suggestions for what could be possible; other ways of being and living. Autonomy has to be understood in the sense of an awareness of how society can be self-instituted. Autonomy in this sense is an articulated project, to purposely live, act, and think in specific ways, and not others. In Castoriadis’ idea of political autonomy, one chooses to recognise a commonality with others, and to develop acts or ways of acting together based on this recognition. Autonomy in this sense is collective, and can also be understood in terms of scale: a nation, a city, a religion, or a club with its members, a political party or, if you will, a gang of saboteurs. Also in terms of kinship, with the human or non-human, it is a connection you make and insist on, not one you inherit and uphold.

In teaching art, the notion of autonomy in relation to collective imaginary is perhaps one of the most central notions in upholding the value and importance of an open process. Since the open process is difficult to validate in the framework of quantification, we need to insist on it for different reasons: We need to be able to trust each other to agree that there are indeed other ways of valuation, and that these can bring us towards different ways of thinking, acting and living – towards other social imaginaries.

But exactly in relation to imagining political action and what it could be, it is clear that the open process should not belong exclusively to artists and those working in the so-called creative industries. Rather, today, – in light of the current political, economic, and especially climate-related crisis – the necessity for being able to push the boundaries for what we can imagine, for what it is even possible to imagine, is overwhelming and a matter of utmost urgency. It is my contention that only through collective imaginaries insisting on the reality and necessity of radically open processes in order to explore what we cannot yet imagine, can we perhaps begin to meet these needs.

Indeed, if radical imagination is today seen as the property, even duty of art, and if rigorous methodology is the remit of science, technology and modern industry, we are now in a historical moment where the radical imagination and capability to experiment is needed everywhere, not in order to supply a market with ever more new gadgets to consume, but in order to imagine how we – collectively – can live in the future, and not least how we can live together with each other, and with and within the world at large. It is, ultimately, not just a question of living, but indeed of survival.

What does it mean to teach artistic practice in the light of open processes and collective imaginaries?

Let me take a detour. Since we teach “art” within our educational system, it seems obvious that art can be “taught”. The premise of the art school is that of a school in its current institutional form: there are disciplines, methods, histories, materials, things to know, crafts to master, skills to pursue – and all these ordered within a set of hierarchies: Some of them are ranked higher than others, some have to be learned before one is allowed to move on to others. The very notion of a ‘degree’ – to obtain a degree through studying – describes this well: a degree of knowledge or skill as a point on a scale. At the same time though, we also have to recognize that the core of what young artists have to learn is exactly not to order their competences and knowledge on a single scale; one ranked before the other. Rather, they have to understand in what ways they each are different, bringing different kinds of competences into a group, and in what ways they can find and build on commonalities. They have to learn to practice their abilities, and through this practice elaborate and develop their methodologies and working processes, inventing new ways of making and thinking. They have to practice how to make use of their actions and tools in dialogue with different contexts, materials and situations. They have to practice the courage to maintain an open processes, the ability to operate in its partial blindness, being able to trust yet develop their own ways of working, building on experience, dialogues, experiments and further learning, and bringing all this into what we can call an artistic praxis.

I deliberately invoke the notion of praxis – from Greek – inspired by thinkers like Plato and Aristotle, but also as invoked by Hannah Arendt.[6] Praxis is related to – but not the same as – ‘practice’ understood as ‘rehearsing’: Repeating an action or gesture in order to understand, learn and develop through doing. Praxis refers to the act of engaging, applying, exercising, and realizing ideas. It implies ways of thinking and ways of imagining. A praxis is a way of taking action in the world, in relation to a set of rules, patterns, skills and knowledge, and in relation to what this world consists of in a given particular situation. An artistic praxis is the continuous enactment, engagement and realization of thoughts, ideas and theories in everyday life. It is pursuing ideas and thoughts until they exist – as articulations, examples or models – for others to meet and engage with. In this sense, an artistic praxis involves making visible. Having an artistic praxis means being in constant negotiation with our surroundings and how we see them; an ongoing thinking, application, dialogue and embodiment of theories, feelings, and ideas, not only for our own enjoyment, but also to make for others to see, experience and perhaps follow. A praxis explores possibilities in order to make them visible – but also to make the exploration itself visible, and thus possible to join. Exploration as model, example, score.

A praxis is a continuous activity. Yet, as described, it does not translate into simply ‘producing one piece of art after another’. Rather, the notion of praxis brings us to the realm of ethics, where actions are assessed on their own and not in relation to a specific end or a specified goal.

Giorgio Agamben explains the difference between morals and ethics through the idea of “means to an end” or “means with no ends”.[7] In politics, a moral argument is always “we have to do X to obtain Y”. In other words, actions are defined by their goal, and evaluated in relation to this goal. The action is only valuable, then, if it gets us to the goal it is designed for. In ethics, however, action stands alone, without a goal. To take an ethical stance is to say for example “we simply do not do this, no matter what the consequences are”. The end does not justify the means. In other words, in the realm of ethics, actions stand alone, and are not evaluated in relation to any goal.

Agamben suggests the notion gesture for an action that can stand alone, without an end:

What characterizes gesture is that in it nothing is being produced or acted, but rather something is being endured and supported.

Agamaben describes a gesture as something that can “endure and support”. What is being endured and supported in an artistic praxis is not only the idea that “something else can be done” – that the work might lead us on new or different routes or directions, or other ways of thinking something we already knew. It is also the suggestion of this to others; the wish to communicate or mediate this possibility as such, making it a social and collectively recognized potential – making it part of a social imaginary. In that sense, an artistic praxis is never alone; it leans on other praxes working in similar fashions, and it helps support them, maintaining that we take space and time for this kind of activity.

Does this mean that the activities related to an artistic praxis are only ‘activities’ that do not produce “anything”, no artworks, nothing to show? No. Rather, staying with Agamben, there is a way out of the reductive dichotomy between “producing something” as a goal, or producing nothing at all. The question is how we understand the idea of “production”. Here, Agamben reads the ancient Roman scholar Varros´ ideas on gestures, and notices that,

if producing is a means in view of an end, and praxis is an end without means, the gesture then breaks with the false alternative between ends and means that paralyzes morality and presents instead means that, as such, evades the orbit of mediality without becoming for this reason, ends.[8]

Gesture here is not connoting empty gesture, as in false and hollow with no real intention or consequence. Instead, gesture is understood as making a means visible as such. The gesture is making the activity of supporting and enduring visible and possible to present to others – to exhibit. In that sense, a gesture is very far from empty, since it aims at mediating – showing, demonstrating, explaining – that this activity is possible; it is part of what is real. A gesture is the exhibition of mediality, Agamben notices, suggesting that we can understand the activity of “exhibiting” very differently from just putting artworks into a showroom. When we make exhibitions as part of our praxis, it is also a demonstration of mediality itself; the fact that we live in language and thus can make means visible as such. Thereby, an exhibition also becomes a suggestion: “look, this is possible to do” – not just in general, but in specific to each single articulation on show. It is not only an object or an image, it is also at the same time a gesture: If this is possible, then what else is also possible?

Instead of teaching students to argue for their choices by the logic of “I want to do X, because then the result will be Y”, I try to help students learn how to develop each a praxis in which it is possible for them to ask “if I do this, then what?”

The aim of an art school thus should not be to produce subjects for a table of ranking, be it academic ranking, the art world or art market-ranking, but rather for the students to learn to participate in active worlding of their own contexts, art worlds as well as life worlds. This involves engaging in activities which have do with world making as poetic, and finding or experimenting with ways in which to engage and sustain in these worlds (rather than adhering to this or that institution and its criteria). It is exactly by dreaming and realizing their own versions of the world, that they take part not only in Art, but in the potential of art and the art of living.

An art school should be an institution in which part of the social imaginary is to insist on the possibility and value of students and teachers helping each other to act collectively autonomous, to deliberately work on imagining together what could be possible and how to make these possibilities visible: ways to work, questions to ask, processes to engage in, commonalities to share.

As always, a social imaginary depends on trust, insistence and hard work in the form of continuous practice – both in terms of teaching as well as learning. Different kinds of groups and relationships in and around an art-school might share and be able to build on very different kinds of social imaginaries, and they might be able to operate more or less autonomous, each in their way. It is part of my job as a teacher to help students understand that they are depending on these groups and their imaginaries; on the contexts and frameworks they decide to join and thus decide to also be part of keeping alive – enduring and supporting. Be it a global sub-culture, or a local group of friends, be it through conviction or activism, through love and affection, or through enjoyment and pleasure, we have to understand that we can in fact choose to endure and support each others´ capacities to imagine other worlds; other ways of being and taking action in the world.

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

In visual art for example, a few selected individuals are allowed to have “open processes” and even be paid generously for them. Still today they are called “geniuses” in order to justify the payment, and through this myth, their names alone sometimes generate enormous prizes.

2.

It is no coincidence that when teaching young artists, I often observe how background in terms of privilege, access to resources, and class often plays a much larger role in succeeding afterwards, than any idea of “talent”. Much more than it is recognized and discussed. We need to ask ourselves who these young people are, who dare to invest their entire education and a lot of work into an area of work that could potentially be “worth” nothing, because it can only be evaluated as either “genious” or else something not measurable? Who has the courage to actually experiment, meaning to “fail” so blatantly and so often, in order to uphold an open process – and where does this courage come from?

3.

The modern use of the notion the imaginary as a noun, stems from French literature (André Gide), philosophy and psychoanalysis, where especially Jean-Poul Sartre and Jaques Lacan popularized the use of it, Lacan using the imaginary as one of three central terms for psychoanalysis: The Symbolic, the Real and the Imaginary. Later, philosophers such as Louis Althusser, Giles Deleuze and Cornelius Castoriadis used the notion to each their specific mode of analysis: Deleuze describes the imaginary “by games of mirroring, of duplication, of reversed identification and projection, always in the mode of the double,” (Deleuze, Gilles. 2004 [1972]. “How Do We Recognize Structuralism?” Pp. 170–92 in Desert Islands and Other Texts, 1953–1974, edited by D. Lapoujade, translated by M. McMahon and C. J. Stivale. New York: Semiotext(e). ISBN 1-58435-018-0.) Cornelius Castoriadis defines the imaginary as the capacity humans have to create other forms of individual and social existence. (Castoriadis, Cornelius. 1996. “La société et vérité dans le monde social-historique, Séminaires 1986–1987, La création humaine I. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. p. 20. Klimis, Sophie, and Laurent Van Eynde. 2006. L’imaginaire selon Castoriadis: thèmes et enjeux. Publications Fac St Louis, p. 70. French: “[L]’apparition chez les humains de l’imaginaire aussi bien au niveau de l’être humain singulier (imagination) qu’au niveau social (imaginaire social ou imaginaire instituant).”)

4.

Cornelius Castoriadis, The Imaginary Institution of Society, 1975.

5.

Just this winter, we saw a US-election and the events around recognising its institutions and thus the election-results as real, being contested and “put to test” as some commentators called it.

6.

Arendt, Hannah: The Human Condition (2018) University of Chicago Press. In her book, Arendt actually uses the notion praxis in order to understand and describe political action. She suggests a distinction between ”praxis” and ”poesis” in order to understand praxis as doing, but a doing with a purpose outside of itself, yet still different from creation (poesis). Arendt sees action as always part of a web of intersecting interactions between people, who don’t necessarily share a common goal. She insists that free people do not share all their convictions or have a common will. Praxis is also related to seizing a moment or taking initiative according to one’s beliefs, and by doing that, inspiring others to join or to do the same.

7.

Agamben, Giorgio: means without end. Notes on Politics (2000). University of Minnesota Press, pp. 56 – 57

8.

Ibid.

is an artist living and working in Berlin, teaching, writing and exhibiting internationally. Her main artistic interests are around the processes through which images, languages and spaces become institutionalised and appear as naturalised, and how these processes influence our way of inhabiting and understanding the world. Katya Sander is Professor at Nordlands Kunst og Filmskole in Kabelvåg, Lofoten, where she is in charge of developing structures and frameworks for teaching, learning and researching artistically for the school at large; i.e. for students as well as for academic staff. Together with Professor Pelin Tan she initiated the research hub Resilient Infrastructures as an example of a framework for content- and interest-driven research in an art- and film-school.

Nordlands Kunst og Filmskole in Kabelvåg, Lofoten www.lofotenkunstfilm.no/offline