Future fiction: an explorative method for self-learning

Marc Neelen and Ana Džokić, STEALTH.unlimited

CATEGORY

“Pressured to find a way out, to plot a necessary long-term strategy to secure ‘our’ survival, we once more decided to call upon future fiction to make a jump ahead.”

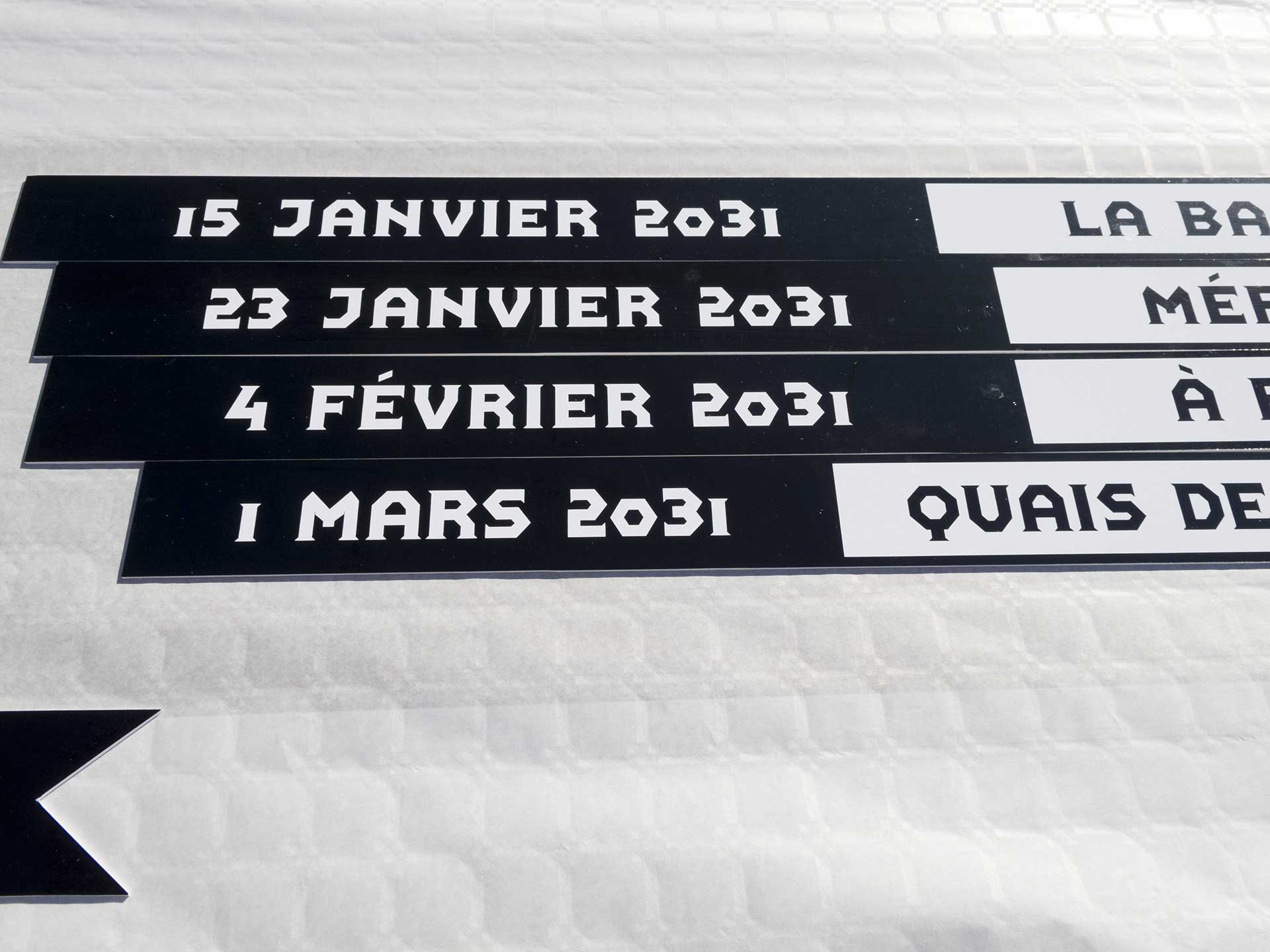

Date tags, part of Once Upon a Future exhibition, Bordeaux, 2011. Photo by STEALTH.unlimited

How can we desire something if we can’t even imagine it yet? How do we anticipate what could cross our path – or obstruct it – if we can’t picture the voyage to arrive there? And to choose the right companions for such a journey, if we can’t envision where to start from? These questions have confronted us increasingly during the last decade while exploring alternate urban futures that might lay ahead. Thus, for us, future fiction has become a method not only to grasp aspirations better but equally to “preview” how such different realities could unfold.

Using future fiction as a playful but equally powerful tool has been a long story in the making. In 2011, a few years following the start of the Global Financial Crisis, we delved into a universe of pioneering communities to understand how they might envision a city (in part) co-created through their collective actions. Their city was Bordeaux, and time seemed right to offer such a future perspective. As large-scale urban developments got stalled across Europe, it looked like space for a different take on the city had opened up. This broader context and a generously funded urban biannual (under the artistic direction of Michelangelo Pistoletto) allowed us, co-curator Emil Jurcan and the architecture center arc en rêve, to envision a horizon different from the usual autopilot neoliberal course. We started from the question: How would the future look if citizens’ collective capacity would grow and become Bordeaux’s primary driving force? It resulted in a piece of social fiction in the format of a novella and exhibition. Once Upon a Future became an imaginary fast-forward to a possible Bordeaux of 2030 – giving an unexpected twist to that target year by which the city authorities aimed to surpass the magic threshold of one million inhabitants.

What started from the ambitions of remarkable but vulnerable pioneering communities on the ground in our hands grew into the silhouette of a 2030 urban reality – in which they are no longer marginalised underdogs but have instead become dominant practices. Working with writer and philosopher Bruce Bégout and a dozen local graphic and comic artists, a still rather abstract future suddenly acquired personalities and names, precise locations, dates and events, colour, smell. It got narration, voices, rhythm and pace. It counted breakthroughs and defeats. It became possible to identify with it, absorb it, or reject it. And in the latter, one could choose to plot a different trajectory instead. Although, to a large extent (still) wishful thinking, drawing it out became an important, empowering and insightful method. To the featured local groups, it opened a possibility to place their endeavours into a larger whole, propelled far enough in time to detach from daily preoccupations. To ourselves, it proved a confrontational experience. Would we be ready to wait some twenty years for such a different city to arrive, or should we instead start acting in that direction?

Once Upon a Future exhibition view at Les Abattoirs, Bordeaux, 2011. Photo by STEALTH.unlimited

Back from Bordeaux and following years of project-based work, we turned our focus back to our home bases, from where STEALTH started – Rotterdam and Belgrade. With friends and colleagues in both places, we initiated the slow and tedious process of co-constructing a future “on the ruins of the collapsed system”.[1] Learning by doing, in real-time, real space, real life, putting together pieces of a puzzle of two long-term community engagements, responding to the unsustainability of the current housing condition. In Belgrade, with Ko Gradi Grad setting up a new breed of non-speculative housing cooperatives, and in Rotterdam, with Stad in de Maak, working with the “toxic assets” of stranded Dutch welfare housing. However, by the late 2010s, following a decade of aftershocks, opportunities opened up in the cracks of the Global Financial Crisis were quickly closing again. What started as ventures into collective, out of the market territories got at risk to get stalled, outpaced by a speculative real-estate apparatus churning at a high pace.

While previously we could identify ourselves as “misfits” of sorts, by that point, too many of us were misfitting. It had become a matter of survival in an increasingly insecure world. Our cities simply no longer support our lives: apartment prices collide with our income situation, spaces do not match our work reality or job mobility, economies do not centre around people but rather around financialised assets, while much of this seems a form of plunder rather than anything else. It is no longer clear who or what does not fit: we, or reality out there, increasingly at odds with a future-proof context for our lives.

Pressured to find a way out, to plot a necessary long-term strategy to secure “our” survival, we once more decided to call upon future fiction to make a jump ahead. The occasion this time was given by the 2019 Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism and its “Collective City” thematic exhibition curated by Beth Hughes and Francisco Sanin. Two close friends and younger colleagues – Jere Kuzmanić and Predrag Milić – joined us in imagining where we would find ourselves ten years ahead. On-track, derailed, or clinging onto some misfitting reality in our enclaves or parallel societies? Fast forward some months, and there we were for an exercise in collective survival. The actual site was the grounds of a reclaimed illegal garbage dump, peculiarly set at the intersection of Hungary, Serbia and Croatia. A patch of fluid territory defined by a constantly shifting Danube river. Reclaimed was not just the site, but also the makeshift encampment: constructed from repurposed construction leftovers, found logs, and fatalities of consumer culture: outdated radios, furniture, expelled fridges. For the days to come, this somewhat post-apocalyptic scenery kept us on edge. When power faded and the freshwater pump receded, we had to resort to buckets of murky water from a dead-end branch of the Danube. Its smell was ominous, but this is where the fish for our lunch arrived from. Apparently, you can have it all.

Site of the “post-apocalypse”, Bezdan (The Abyss), 2019. Photo by STEALTH.unlimited

We brought along the book Radical Technologies: The Design of Everyday Life by Adam Greenfield. Its ominous black cover provided a travel guide of sorts for decades to come, featuring several scenarios derived from the cookbooks of futurists and corporate foresight departments. Against the backdrop of the seeming post-apocalypse of the reclaimed garbage dump and daily electricity blackouts, we choose for the context projected in the Widening Gyre. In words of Greenfield introduced as: “[…] a pathway in which a thermodynamically sustainable alternative for proof-of-work is discovered, and blockchain-based cryptocurrency goes on to fulfil all the expectations its original champions held for it. This precipitates the withering of the state everywhere on Earth. With the government’s ability to sustain itself on tax revenue decisively undercut, it crumbles and fades – but does so before any kind of societal-scale coordinating process that might be able to replace it has had time to evolve.” Now, how do our current endeavours perform in such circumstances? And are we well accompanied for such a trajectory?

In response, we decided to plot survival strategies that might fall upon three communities in our three cities. First, the residents of Split, an abandoned tourist destination after the last budget flight had left town. They re-purpose abandoned hotel facilities as a work-from-home environment. Second, in Belgrade, an outskirt community next to the airport finds itself in the way of shifting global food supply lines after climate change robs entire nations of their subsistence. As their neighbourhood gets threatened to get bulldozed to make a runway extension, they construct a community-owned energy plant on-site to save the district. And finally, a group of “misfits” in Rotterdam, with their future running out, come up with a daring plan to adopt the wreck of an iconic green investment gone bust. Three communities uncomfortably propelled into an imaginary future.

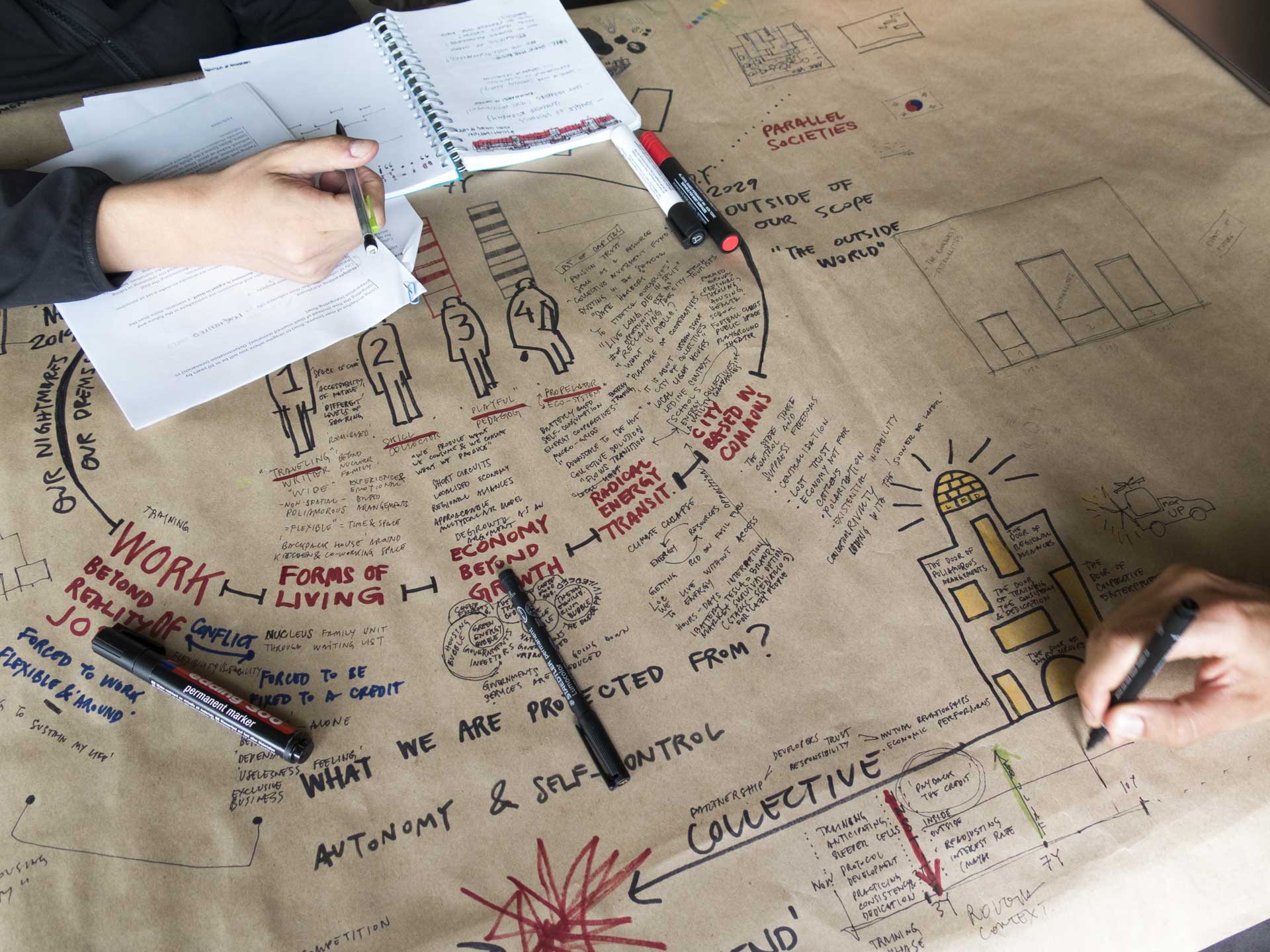

Drafting future scenarios 2029, process for Enterprises of Survival, Bezdan, 2019. Photo by STEALTH.unlimited

Sketching the various future scenarios on thick brown packaging paper has been something incredibly liberating. For one, it helps to articulate the boundaries, the difficulties and the challenges that are ahead. And equally, it functions as a drafting tool for those futures that might be desired. At the same time, anticipating the scope, speed and impact of possible futures remains a tricky endeavour. Like, it would take less than a year to find Split actually abandoned by budget flights, its tourist facilities wrecked by a tiny string of ribonucleic acid known under the name Covid-19. In Belgrade, a community we are part of is meanwhile gathering around a future solar power plant. And in Rotterdam, our street under threat of eviction is right now looking for the next wrecked opportunity to inhabit. Sometimes the future is uncomfortably nearer than one had imagined.

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

In the words of Paul Kingsnorth and Dougald Hine in the 2009 manifest Uncivilisation: The Dark Mountain Manifesto

are architects working and living between Belgrade and Rotterdam. In 2000 they founded STEALTH.unlimited. Although initially trained as architects, for over 15 years their work is equally based in the context of contemporary art and culture. Through intensive collaboration with individuals, organisations and institutions, STEALTH connect urban research, visual arts, spatial interventions and cultural activism. Ana Džokić was trained as an architect at the University of Belgrade and completed a two-year postgraduate program at the Berlage Institute in Amsterdam. In May 2017 she received PhD at the Royal Institute of Art (KKH) in Stockholm, with a practice based research titled Upscaling, Training, Commoning. Marc Neelen received his degree in architecture at the Delft University of Technology in Delft, and from 2012-2017 held the position of a visiting professor at the University of Sheffield, School of Architecture.

STEALTH’s curatorial interventions are a base for projects that, since 2004, mobilise thinking on shared future(s) of the city and its culture in a/o Teasing Minds at Kunstverein Munich, Archiphoenix at the Dutch Pavilion at the Architecture Biennial in Venice, the Tirana International Contemporary Art Biennial, IMPAKT festival Matrix City in Utrecht, the fiction-based project Once Upon a Future for the Evento biannual in Bordeaux, and the exhibition A Life in Common with Cittadellarte – Fondazione Pistoletto in Italy.

Their spatial interventions, since 2006, include a 600 m2 interactive installation at Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam, a public art commission for a schoolyard in Knivsta, Sweden, made in collaboration with artist Marjetica Potrč, a three months long hands-on intervention in public space made in collaboration with Röda Sten Konsthall and the local community of Gothenburg, a cultural development node out of recycled materials in a slum neighbourhood of Medellín, Colombia, made with the art group El Puente_lab.

For about fifteen years STEALTH investigates the urban developments in Western Balkans, starting from their Wild City research on the massive unplanned transformation of the city of Belgrade since the 1990s. Since 2009, STEALTH have been running four editions of the Cities Log research that investigate the roles of different players in the development of cities in the region. A(u)ction, the Novi Sad edition of this project received Ranko Radović Award in 2011. As part of Unfinished Modernisations project, they produced Kaluđerica from Šklj to Abc in 2012, an illustrated narrative on a dream of just legalisation of this, one of the largest informal settlements in the Balkans.

Since 2010 STEALTH co-initiated the platform Ko gradi grad (Who Builds the City) in Belgrade and within it in 2012 the long-term community based project Smarter Building. In 2013 they formed Stad in de Maak (City in the Making) association in Rotterdam to, through a ten-year long process, tackle the “toxic assets” of the stranded Dutch welfare housing.

As for Once Upon a Future in PDF format (English): https://stealth.ultd.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/booklet_EN_web.pdf