Villager pedagogies and backpack organisers in Hong Kong

Michael Leung

CATEGORY

“For now and in the myriad message groups and activities that have come from the Land School we persist, as “backpack organisers” who use whatever tools, methods and strategies that we can when facing unjust dispossession and destruction of everyday life.”

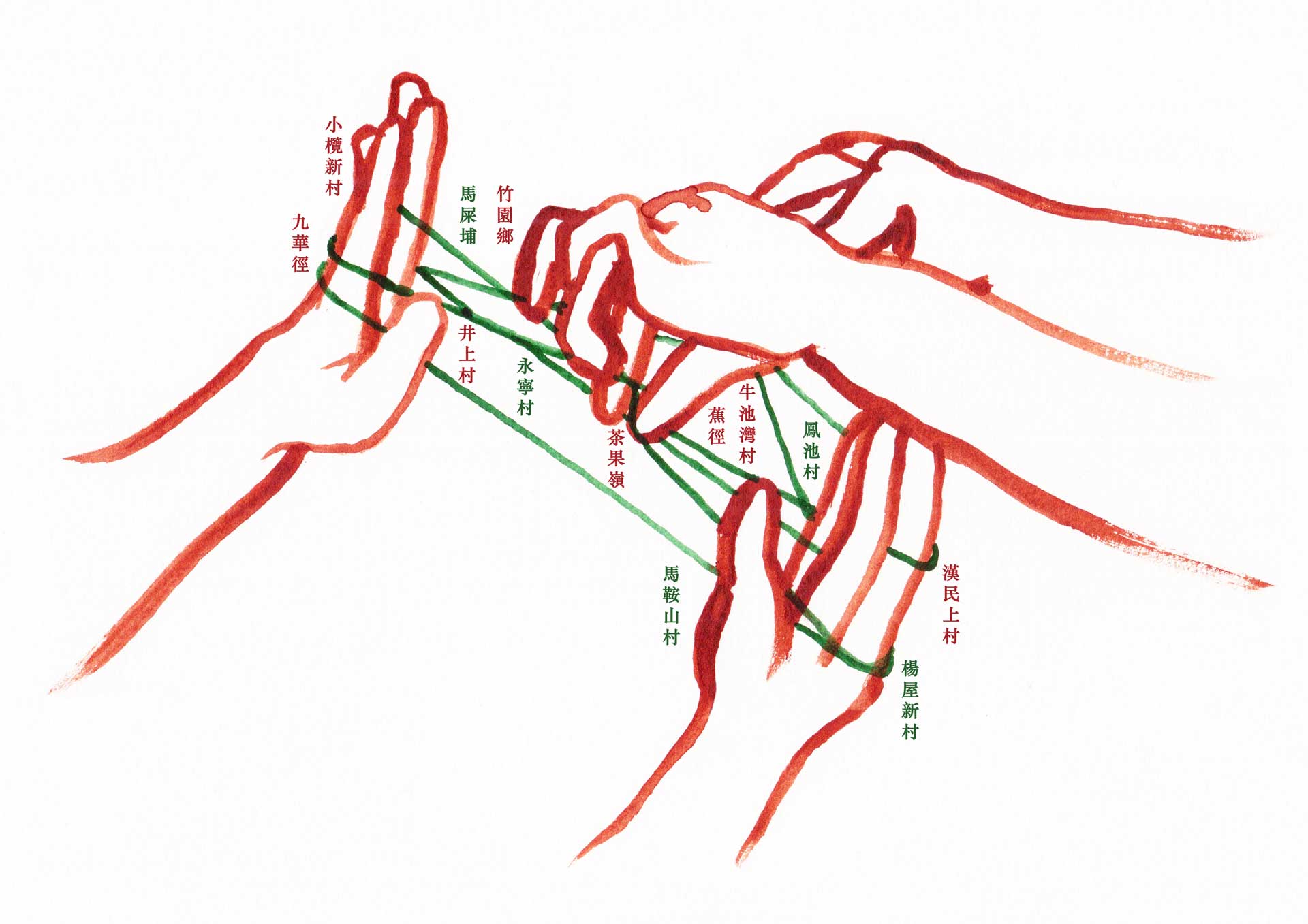

Part-time Pedagogies: Introducing Three Places for Emancipatory Learning timeline, watercolour painting by Michael Leung, 2018[1]

It is already the end of January 2021 and one year since the outbreak of COVID-19. This morning the Hong Kong government ended an “ambush” lockdown, a 4 am spontaneously-announced 48-hour confinement in the neighbourhood of Jordan in Hong Kong—five blocks away from where I write. Writing about urgent pedagogies, recognises the biopolitical entanglements that have created the current muted situation where critique, practice and emancipation can be interpreted as dissent and sedition.

This essay continues on from the ideas in a former text entitled, Part-time Pedagogies: Introducing Three Places for Emancipatory Learning, an essay and timeline painting published online by non-profit arts institution Asia Art Archive. It builds on my part-time university affiliations and daily practice—acknowledging the precarities, privilege and potentialities of part-time lecturing—and shares how an alternative and radical pedagogy can keep growing in the Hong Kong context, amidst the ongoing pandemic, the evolving anti-extradition bill movement (since June 2019) and under the all-encompassing national security law (imposed in June 2020).

The aforementioned timeline painting illustrates two jackfruits, one unpeeled in 2017 and another peeled in 2018. The latter jackfruit is near a yellow banner and looks right going beyond the page. The yellow banner, in its original form, is around 1.7 metres wide and made by Wang Chau villager Ms. Cheng for the 2018 Wang Chau Jackfruit Festival. The annual festival started in 2017 and was conceived in a meeting between villagers, the Wang Chau Green Belt Concern Group and land protectors from a previous land resistance in Ma Shi Po Village in Fanling, Hong Kong (2016). [2]

The inaugural jackfruit festival came after three years of resisting the Hong Kong government’s development plan in converting three greenbelt villages in Wang Chau—home to 500 people, 1,057 trees and multispecies inhabitants—into nine public housing blocks to accommodate 4,000 units (significantly reduced from the originally proposed 17,000 units).

The “strategic” three phases of development and various government, developer, rural committee and gangster relations are described in (self-)published texts entitled, Flowers (Soil and Stones, Souls and Songs), The Emergence of the Jackfruit Woman and Wang Chau Village: (Non-)Indigenous Wisdom, Amidst Eviction.[3] The texts share my relationship and solidarity with the village and all its inhabitants since meeting them in February 2017.

2020 Wang Chau Jackfruit Festival at the Au Yeung family home, Fung Chi Village, Wang Chau, 11 July 2020. Photograph by Kevin Cheng.[4]

In 2017, the jackfruit festival was co-organised by villagers, the concern group and supporters (like myself) to share the villagers’ jackfruit produce with the public, their stories and plight in keeping their homes and protecting the green belt. The festival is a public event and has taken place four times. During the jackfruit festivals visitors could: learn when and how to open the sticky jackfruit; participate in banner making workshops; learn how to grow and use different (medicinal) plants such as 貓鬚草 (Cat’s whiskers) and 魚腥草 (Fish leaf) at the Plant Sharing stand; join village tours that included 打水 (“hitting water,” a method of collecting water from a well); silkscreen print on Pang Jai fabric market-made furoshiki cloths; paint murals together; watch (and engage) with performance artists; participate in discussions with NGOs, academics and activists from other land struggles; read printed matter on the villagers’ resistance; upcycle natural materials into anthropomorphic jackfruits; decorate and make jackfruit masks; write messages of support under a five-metre long timeline; discover jackfruit recipes such as a vegetarian jackfruit curry and jackfruit mead; drink herbal tea grown and served by Ma Shi Po villagers; weave baskets with Choi Yuen Tsuen villagers; sing along to songs written during the villagers’ resistance; join the Jackfruit Tree Adoption Project; and more![5]

The conviviality happenings at the jackfruit festival may seem slightly distant from the urgency of villagers keeping their homes, however the event highlights the importance of participation, making the journey, and further illuminates opportunities for people to engage in prefigurative politics. In other words, to borrow from the Research Group on Collective Autonomy, actively ‘[…] take a position against all forms of illegitimate authority, all forms of oppression and domination which are considered to be interconnected and mutually reinforcing: capitalism, imperialism, colonialism, patriarchy, heteronormativity, and sometimes anthropocentrism and ableism.’[6] Prefigurative politics is practiced in everyday life, through the repetition of convivial encounters and happenings, individually and collectively, and weaved together to form a network of mutual aid; that can be constantly repaired and shared with other movements. This is how pedagogy can be urgent, when future movements don’t need to start from zero, again.

Bitter leaf from Wang Chau Village planted by villager Goo Jei in a communal farm near her new home,

Siu Hong, 23 January 2021. Photograph by Michael Leung.

In previous Hong Kong land struggles and the ongoing Wang Chau movement, the rallying slogan 不遷不拆 (No Eviction, No Demolition) is/was common. Unfortunately the villagers, concern group and supporters’ numerous attempts in communicating with the government were to no avail, and through the implementation of inequitable policies and top down land rezoning enforced by security guards and the police, the strategic and gradual dispossession of villagers’ homes has accelerated since July 2020. A day before his passing I was reminded of anthropologist David Graeber’s ‘against policy (a tiny manifesto)’ and that, ‘By participating in policy debates the very best one can achieve is to limit the damage […].’ [7] Today, the several remaining villagers, their homes and gardens (in Wang Chau and elsewhere) continue as places of knowledge production through the cultivation/relocation of plants, gifting of clippings and produce, and the passion to stay connected to the land—even when their homes become construction sites or if they live elsewhere.

Since coming back from a five-month Europe trip in June 2020, I have been going to the New Territories, the urban/rural/mountainous northern part of Hong Kong, at least three days a week.[8] I go to the New Territories to support the remaining Wang Chau villagers and witness the eviction (sometimes by taking drone footage), teach my friend’s son English as part of a gift economy, and to purchase organic vegetables from Mapopo Community Farm in Ma Shi Po Village.

At the beginning of December 2020 I made an application to join the “Land Primary School” (土地小學), a four-day camp organised by Land Justice League who are a Hong Kong activist group that focuses on sustainable development, preserving the natural environment, agriculture, housing, and democratic land planning.[9] The application included five thesis-length questions such as, ‘2. What problems does Hong Kong agriculture face and how should it proceed?’[10] Fortunately I was accepted and invited to join a messaging group for further updates.

13 villages in Hong Kong proposed for development by the government, 14 November 2020.

Watercolour by Michael Leung.

The pre-camp gathering happened on 20 December 2020 in Ma On Shan Village, one of 13 villages proposed for development by the government—my second visit to the former mining village. The gathering of 16 people included Ng Cheuk-hang, a member of Land Justice, asking us all what we expect to learn from the Land School and what constitutes a village—the latter sticking with me when visiting other villages.

Whilst tying up some tall heirloom tomato plants, TV a farmer friend asked me last week, “When you go to Wang Chau every week, do you ever feel like you don’t know what you’re doing there?” I said no, and elaborated.

At Wang Chau, some villagers have been practicing a prefigurative politics, even during the dispossession of their homes and gardens. I have seen villagers: reconnect/pirate their water and electricity supply after the government unjustly cut them off; build tool sheds that border on the government’s development zone; patiently photograph their Chinese medicinal plants and publish them into a zine; practice traditional bone-setting from their home; run a Chinese medicine clinic from a storage container; “illegally” modify electric bicycles with trailers to help transport metal for recycling; make use of fenced public space for growing food; share storage space with late night food vendors and their carts; rent out affordable housing to others; and socialise around mahjong tables under self-built shelters in public space. In other words the villagers have shown how to survive and thrive in one of the most expensive places on this planet; before the government decided to evict them.

In a recent text, anonymous authors write, ‘We find potentialities in our shared sensitivity: that sense of urgency that pushes us to seek new ways of living — to want to change this world; that feeling of belonging that pushes us to act, and likewise to risk everything. How can we unleash these potentials?’[11] Some Wang Chau villagers have been world-building, together; even amidst precarity. As an artist-researcher and supporter, I want to be there to bear witness and share those few remaining weeks with the villagers—in situ with soil under my fingernails, and in my writing, so that we persist in building a more livable world together.

Back to the Ma On Shan pre-camp, villagers Tamara and Hong walked us through the mining history of the village and shared stories: one relating to a small shed, made from natural materials and built against a large rock, that was previously used as a kitchen to steam cha guo (tea cakes) for the miners in the 1960s; and another story of how their family continue to upkeep a 134-year old grave, whose ancestors have only visited once in several decades. This was the first time third generation Ma On Shan villagers had organised such a comprehensive tour, one that will happen again and include a four-hour walk in total darkness from one side of the mining cave to the other.

Land School “shoe barricade,” Shun Sum Yuen, 29 December 2020. Photograph by Michael Leung.

The seventh Land School started on 27 December 2020 and brought us to a Shun Sum Yuen, a commercial flower garden in San Tin run by farmer Shun Gor, who in 2016 started welcoming people to volunteer and grow rice together.[12] The school’s 24 participants came from different backgrounds: from secondary school students to Earth Science graduates, from graphic illustrators to theatre producers. Following our circle of introductions we discussed the importance of self-organised villager-led movements, and how we, as supporters, can share information and support when needed, so as to not “hijack” movements but allow them to develop naturally and at a pace comfortable for the villagers.

I recall villager Mr. Chan’s observation that in Wang Chau there are actually two simultaneous movements: one by the villagers who want to keep their homes and rural life, and the other by “outsiders,” those who are committed to protect the land and biodiversity in and beyond Wang Chau. I agree that there can be multiple and overlapping movements—part of whatever is left or possible of the anti-extradition bill movement too.

When we befriend villagers and share life, our relationship with the village transforms and our politics sharpen. In April 2020 amidst the pandemic, movement-builder Thenjiwe McHarris said, ‘This is a moment of learning, a moment of growing, but this is also a call to action. We are in a moment of crisis but we’re also in a moment that is requiring us to be our boldest, most powerful selves.’[13] How can words that emerge from other movements responsibly influence our own, and nourish us and the actions to come? How do we work together to abolish all forms of oppression and domination?

Sharing and lunch at a villager’s home, Banana Path, 28 December 2020. Photograph from the Land School messaging group.

On the second day of the Land School we visited Banana Path (Tsiu Keng), a thriving farming village that the government has planned to zone, clear and manage as an 80-hectare “Agri-Park,” replacing farmers’ spacious village homes with rented 15-square-metre “basic lodging units” for “temporary resting.”[14] During breakfast a farmer called Ah Fan Jei shared her farming experiences with us. During our discussion she expressed her curiosity to know more about the school’s participants—what the younger generation think about how land should be used in Hong Kong, how to make organic produce more accessible to people in Hong Kong, how to mobilise the support of wealthy friends, etc. We shared ideas before walking to another villager’s home which is radically sustainable. The Land School is a web that connects people to specific contexts and communities, and creates possibilities to solve challenges together, on-site—allowing a radical pedagogy to expand.

The rest of the Land School included: farm tours; lectures from artists, historians, community organisers and social workers; engaging workshops; manual and automated farm work; and in-depth discussions—that continued until 2 to 4 am! Throughout the school I kept reflecting on my relationship to Wang Chau and the villagers, and what else could be done during an inequitable eviction. For now and in the myriad message groups and activities that have come from the Land School we persist, as “backpack organisers” who use whatever tools, methods and strategies that we can when facing unjust dispossession and destruction of everyday life.

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

https://aaa.org.hk/en/ideas/ideas/part-time-pedagogies-introducing-three-places-for-emancipatory-learning [22-10-2021]

2.

https://dungbak.tumblr.com [22-10-2021]

3.

https://insurrectionaryam.tumblr.com/texts and Michael Leung, “Wang Chau Village: (Non-)Indigenous Wisdom, Amidst Eviction”, British Art Studies, Issue 18, https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-18/mleung [22-10-2021]

4.

www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=3035411116496829&id=194035600634409 (www.tinyurl.com/1ourd9xs)[22-10-2021]

6.

Émilie Breton, Sandra Jeppesen, Anna Kruzynski and Rachel Sarrasin (Research Group on Collective Autonomy), ‘Prefigurative Self-Governance and Self-Organization: The Influence of Antiauthoritarian(Pro)Feminist, Radical Queer, and Antiracist Networks in Quebec’, in Aziz Choudry, Jill Hanley and Eric Shragge, Organize! Building from the Local for Global Justice (Oakland: PM Press, 2012): 157.

7.

David Graeber, Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology (Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2004): 9.

8.

https://insurrectionaryam.tumblr.com/2020 [22-10-2021]

9.

www.facebook.com/landjusticehk [22-10-2021]

10.

https://landjusticehk.org/2020/11/14/2020 [22-10-2021]

11.

https://illwilleditions.com/re-attachments [22-10-2021]

12.

www.instagram.com/shunsumyuen [22-10-2021]

13.

www.facebook.com/WorkingFamilies/videos/1001191743609133 [22-10-2021]

is an artist/designer, researcher and visiting lecturer. He was born in London and moved to Hong Kong eleven years ago to complete a Masters in Design at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. His projects range from collective agriculture projects such as The HK FARMers’ Almanac 2014-2015 to Pangkerchief, produced by Pang Jai fabric market in Sham Shui Po. Michael is a visiting lecturer at Hong Kong Baptist University where he teaches social practice (MA). He is currently doing his PhD at the School of Creative Media, City University of Hong Kong. His research focuses on Insurrectionary Agricultural Milieux, rhizomatic forms of agriculture that exist in local response to global conditions of biopolitics and neoliberalism. In 2014 Michael started writing fiction, self-publishing and reading them in public space. He contributes monthly to Fong Fo, an artist zine printed on the 21st of each month.

Michael Leung website: www.studioleung.com