Building spaces for learning together in freedom

Interview with Gustavo Esteva by Magnus Ericson and Pelin Tan

CATEGORY

Gustavo Esteva discusses the urgency and needs of Universidad de la Tierra /Unitierra (University of the Earth) – which is an autonomous university and an alliance of collectivities engaged in learning through action, based in Oaxaca. From his ideas and long experience in how to create spaces for learning, he explains a decolonial attempt of an urgent pedagogical initiative that fights for indigenous people’s rights.

Gustavo Esteva at Universidad de la Tierra, Oaxaca. Still from Re-learning Hope: A Story of Unitierra, a film by Udi Mandel and Kelly Teamey.

Universidad de la Tierra /Unitierra (University of the Earth) is an autonomous university and an alliance of collectivities engaged in learning through action, based in Oaxaca, Mexico. It attempts to respond to the recognition, particularly among indigenous peoples, that the dominant state-supported educational structure prevented children from learning what they needed to know to continue living in their communities and contributing to the common good of their communities and the sustainability of their territories.

Magnus Ericson: To give us a background, can you tell us a little how Universidad de la Tierra or Unitierra was founded and how it all started?

Gustavo Esteva: Well, we were born as an expression of social struggle and we are still associated with social struggle. In 1997 at the Indigenous Forum of Oaxaca – Oaxaca is the state where I live and where the majority of the population are indigenous people – a public declaration was presented after a year of discussions. It claimed that the school has been the main tool of the state to destroy the indigenous people. And they were just reclaiming a historical truth; education in Mexico was created in the 19th century to de-Indianize the Indians. And in a very real sense they succeeded, millions of people entered the system as indigenous people and came out as citizens of fourth or fifth category but no longer indigenous people. Then the indigenous people of Oaxaca were saying basta! enough! We don’t want more of that! And they started to close the schools and kick the teachers out.

You can imagine the scandal, and the front page in the papers were saying “they are barbarians, this is not possible! We cannot allow this to happen!” And there was a lot of political and economic pressure on them, but some persisted and kept their schools closed. Then, a good anthropologist decided to teach the parents a lesson and he produced some tests to compare children going to school with those not going to school. And to his surprise, and the surprise of many people, he discovered that the children not going to school, of course, knew everything about the community, how to live in the community, the meal plan and everything. But they also knew better than the other children about what their schools supposedly should be teaching, for example, reading, writing, arithmetic, and they were even able to answer the questions about geography or history.

This was a really great surprise, but of course the communities were very, very happy with this outcome. The same communities were really enjoying this opportunity for the children to learn in a different way, came to us with their concerns. What will happen with the young men and women, once they learn everything they can learn in the community, but are still interested in learning more? Since they don’t have any diploma or any certification of their studies, they will not be able to continue their studies.

So then, with them and for them we created the Universidad de la Tierra. It is a coalition of indigenous and non-indigenous organizations. Jaime Martínez Luna, a brilliant Zapotec intellectual, gave us our name. He said that this university should keep its feet on the ground and on the earth, and it should care about Mother Earth.

We adopted the principle of learning by doing, meaning we don’t have teachers, we don’t have curricula, we don’t have classrooms. We learn by doing whatever we want to learn with someone doing that, with someone who knows how to do that, and is ready to share what she or he knows with other people. We are not involved in any form of professional formation, because we find the professions counterproductive. Basically, all the professionals disqualify the wisdom, the knowledge and the abilities of normal people. We are trying to de-professionalize ourselves. We don’t have a political agenda, we take on the political agenda of the social movements in Oaxaca and we follow what they want to do, what they want to learn, and what they want to create. This is how we have been working now for 20 years, following that path and learning many things from the communities and from the young men and women who come to learn with us.

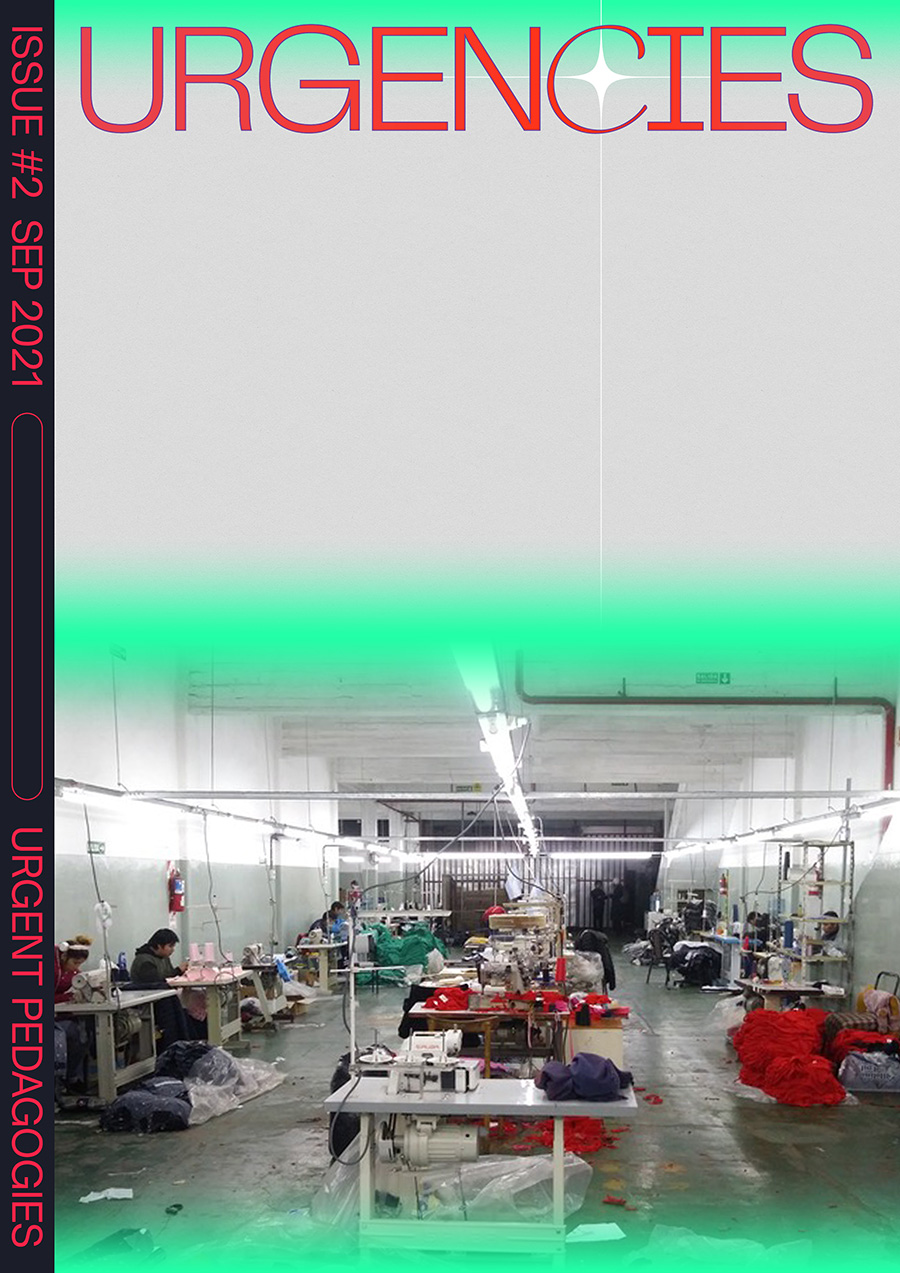

Unitierra in Oaxaca. Still from Re-learning Hope: A Story of Unitierra, a film by Udi Mandel and Kelly Teamey

Magnus Ericson: Can you tell us a little bit how your practice and your personal journey through different kinds of engagement somehow lead up to this? I know that you have a background working in different kinds of political, public and private spheres, and through different encounters with pedagogy. I know that you have met and collaborated with Ivan Illich and it would also be interesting to hear about this. Perhaps it’s a long story but…

Gustavo Esteva: Yes, it’s a long story, but I will try to make it short; and it is in fact two different stories, one is my personal story. I was part of the first generation of new professionals in Mexico, the market was waiting for us and we had great, great success. I became a Personnel Manager in Procter & Gamble, when I was 19 years old and a little later, I also became a Personnel Manager in IBM Mexico. I received a lot of prestige and money, but both companies fired me because I refused to do what they asked me to do. And after trying to continue to work through my own professional bureau, I decided to abandon this profession when I was 23 years old, because I discovered that it was impossible to live honestly this way, and to work within the corporations in the corporate world with this profession I had.

Because of the condition in Mexico and the world, in the time of Fidel Castro in Cuba, there was a great mobilization in Mexico. I became a leftist and then a Marxist, and I joined a group that was going to create the first guerilla in Mexico. It was the time of Che Guevara and he was the model for us and for all of us in Latin America, and we had the moral obligation to start the revolution with a guerilla.

We asserted that movement and we started to learn how to become violent, and after a spectacular failure we abandoned the idea of violence but not the ideals of the revolution. And since the main idea of the guerilla is to seize the power, we joined the government to seize power. In the seventies we got a populist president in Mexico, and then suddenly, I got an immense amount of power. I was at the presidential house every week, and I was involved in cabinet meetings and participating in many different ways in the orientation of the government’s fantastic development programmes. Then because of the success of these programmes in the seventies, during this populist president’s time, suddenly I faced the immediate danger of becoming a minister. I quit because by that time, I knew that the government was not the place to produce the change we needed. The government was for control and domination, and not really for the deep change that we were dreaming about. So, then we created, with some friends, independent organizations to work from the grassroots and since then, I have been working with the people, and basically with the indigenous communities and with peasant and urban marginalised communities in Oaxaca and around Mexico.

I was mentioning that I must include another story, because when I was in my twenties and my first daughter entered school age, I started to look around for a good public or private school to which I could trust my beloved daughter. I could not find one. And then with some friends I created an alternative to school, what was then in the sixties called an “active school” in the lines of Freire. We added one year every year for my daughter to be able to continue her studies. When she ended High school we closed the school, that was really a very beautiful school. We had tried with Freire’s ideas, but also by using ideas from for example Waldorf, Montesori and other approaches for alternative education.

But after 11 years of experimenting with this beautiful school, we discovered that the problem was not the quality of the school, but the school itself. And then my daughter did not continue studying at university, but tried to follow an alternative path. We continued with different kinds of experiments until I met with Ivan Ilitch in 1983. When he was at the peak of his fame in the early seventies, he was just sixty kilometres from the place where I was living. But for us in the Marxist left, he was just a reactionary priest and we assumed that it was not interesting to read him. Of course, he was talking against the capitalist education and health system in the capitalist society, but we assumed that in a socialist society we will have good education and health service, like Cuba had already demonstrated was possible.

But in 1983, just by accident, I met with Ivan and I immediately liked what he was saying. I started to frantically read all his stuff and we became friends, and collaborated until the end of his life; and I discovered many, many things with him and of course the radical critique of education. It was because of what I learned with Ivan that I discovered that the question was not to really to create an alternative education and different forms of alternative education, but alternatives to education. We need to abandon the very idea of education, I even wrote a book called “Escaping Education”. We need to run when someone tries to educate us – as the whole society was trying to do. I think it is important to say that ten years after publishing ”De-schooling Society”, he wrote a brilliant essay, saying that he had been barking at the wrong tree. Because the question was not just about the school, but the whole of society that was educating us and forming us in a certain way. And that was more or less the two stories in one, that I think can be pertinent for our conversation today.

Pelin Tan: Gustavo, can I ask you… I was curious about the fact that in 1996, you were the informal advisor of the negotiation of San Andrés Peace Accords between the Mexican Government and the Zapatistas, and then you were very engaged as a mediator. I know that the Zapatistas have a school themselves with an alternative curriculum and so on. Can you tell me a little bit about the differences and similarities between your school and theirs, and why you didn’t join their model? Perhaps I can ask you what was triggering you to relate your school to social and political movements, and engaging indigenous communities?

Gustavo Esteva: First of all, the Zapatista schools are not really schools. Like with many other things, they put their label on something that is radically different. For example, in the Zapatista schools they don’t have teachers or curriculums. They are promoters of education because they still use the term “education”. They came together in the mornings to a place with their children, and they started by discussing what to do and how they wanted to explore different things. They were open, they listened to many different views, and they accepted teachers that were trying to educate them. They listened and they were following them for some time and then they said, thanks but no thanks. We are not interested in that kind of education, that kind of school or that kind of orientation. They have a radically different view on learning, and learning in freedom – and all rooted in their own communities. But you cannot talk about one Zapatista school because all of them were different. Every community makes decisions and they don’t have a system of education. They don’t have a program to educate all the children in a certain way, or to create a specific way of being a Zapatista. They were open to many differences and different Zapatista communities had different conditions for learning.

They invited about six or seven thousand people for the “Escuelita”, the little school, to teach about Zapatista life. Then these people, and myself included, were distributed over many different communities, not just the most functioning ones, but also communities with a lot of problems. All of us, in different conditions, were learning with the communities – without a curriculum, without any specific programs – how they lived. They set us up with a person to respond to our questions. The curriculum was our questions – this is what they would teach us. Then of course we learned many different things, because we were in different communities. That is in a real sense the opposite to a pedagogy or to a curriculum or a school.

Zapatista school. Still from Re-learning Hope: A Story of Unitierra, a film by Udi Mandel and Kelly Teamey

Then I would like to go back to 1994 when the Zapatista uprising started. I was, like millions of people, very, very excited and I was in the streets supporting them; and on the second day, I was asking myself, Gustavo, what’s happening to you, why are you so enthusiastic about this movement that is an army and a violent uprising? For thirty years you have been against violence and you abandoned the idea of violence, why are you so excited? And then I read again Gandhi when I discovered a story that I did not know before; Gandhi had suffered an attempt and then his son asked his father: What should I do if a guy comes trying to kill me, or hurt me? Should I preach non-violence? Gandhi laughs and says: when you are the weak one, the only thing that you must not be is a coward. If non-violence is the supreme virtue, cowardice is the worst sin. Then you must not be a coward. And for the weak perhaps there is no other option than violence. If I am preaching non-violence to the people in India, it’s because they are strong. I don’t see why 200 million people are afraid of 150 000 British because they are strong. They should use non-violence, that is the best way to achieve political goals.

This was a brilliant lesson for me, and I think it is a very good story to understand the Zapatistas. Because they were suffering and dying like flies, and they were in an extreme degree of oppression. They said that the only thing left for them was their dignity, and they were using their dignity for the uprising, and they therefore started the armed uprising as a last resource. They did not assume that they would seize power and occupy the state, they were very weak. They assumed that they would die, that they would be exterminated, but perhaps because of their deadly sacrifice they thought that the society might react. They have tried everything, including that impressive march of two thousand people walking into Mexico City. Nobody heard them, neither the society nor the government, and then they tried the guerilla as a last resource. Then after seeing millions in the streets, and also getting support, we were telling them that we are with you, we are supporting you, but we don’t want more violence. When the government declared a ceasefire because of our pressure, twelve days after the uprising, the Zapatistas immediately stopped. And since then, twenty six years later, they have never again used their weapons. They still have their weapons, but they are not using them, not even for self-defense.

They embrace non-violence, also because now they are strong and no longer weak. A few months later, when the dialogue with the government started, famous Sub-comandante Marcos confessed in public that they were prepared to fight, that they were not prepared for dialogue, but that they wanted to learn. And they started the dialogue, and when this first dialogue failed, they started a second dialogue in 1995, and invited more than a hundred advisors. I was one of them, selected as one of twenty for the negotiations with the government. We were advisors only for the negotiations with the government, we were not really advising the Zapatistas, or the movement or whatever. We were advising them as kinds of mediators between the government and the Zapatistas. We participated in this round of negotiations that resulted in the San Andrés Peace Accords after six months. In the process, they convened the National Indian forum because they wanted to present not only the Zapatistas’ views but also the view of the indigenous people. And then indigenous people from the whole country came in January 1996 to present their views. The Zapatistas brought them to the negotiation table to include them in the agreements of San Andrés.

Magnus Ericson: In what way did this influence today’s situation for the indigenous population in Mexico?

Gustavo Esteva: Only in one sense, because the agreements have not been translated into law, constitutions or administrative practice. So, what we learnt with the Zapatistas is that we cannot trust the government, and we cannot hope for change from the government or the institutional system. We learnt that we need to follow our own path – only in that sense, it had an influence.

Magnus Ericson: So, this has meant that you have to work mainly from bottom up now?

Gustavo Esteva: Yes, that is the main idea. Instead of trying to have any kind of arrangement or thinking that we may have a left government – like we supposedly have now – or progressive policies, we know that it is not possible to really get anything from the government, except oppression and aggression. We need to protect ourselves from the government, instead of asking the government to do something productive.

Magnus Ericson: And perhaps create possibilities of empowerment through, for example, education? But I should of course not use the term “education”…

Gustavo Esteva: No, “learning”. This is very important for us, and what we learnt from the Zapatistas is that using nouns like education or health creates a radical, brutal dependency of someone. If you say that you need education, then you need an educator to educate you, and if you think you need health, you need someone offering you health services. But then if you instead of using nouns use verbs, you reclaim your agency. If you are talking about learning, you are then coming back to your own capacity to learn. No one is learning for you. You are the person learning, and you are the person eating, healing and dwelling, and you have the agency again to follow your own path in freedom. And this is why we don’t use the term education.

Magnus Ericson: It would be interesting to hear from you about what kinds of urgencies you are facing now in Mexico and of course in relation to the context of Unitierra. It would be nice if you could tell us about the current situation – even if I suppose many struggles are still the same?

Gustavo Esteva: Yes of course we can discuss, but I just want to clarify one thing: as advisors we were not advising the Zapatistas about their movement, only in relation to the negotiation with the government. When the negotiations ended, we ended our engagement with the Zapatistas. I have been invited by them for many different kinds of activities, but no longer as an advisor. But I was honoured with that invitation back then, for a very, very precise activity.

Pelin Tan: Yes, this is totally clear. But Gustavo, we’re interested in, as Magnus said, both what topics you are engaging in, and what kind of educational strategies you are using at Unitierra?

Gustavo Esteva: We are not engaging in any kind of education. We are abandoning the very idea of education, all forms of education. We don’t want to educate anyone, and we don’t want to be educated. We are learning together, and we are learning in freedom, and that is our basics. Sometimes when people put pressure on us, and ask us what is the pedagogy you are using at Unitierra?, we say that we are not using any pedagogy, and if they insist, we say that we use the pedagogy used with babies. Babies learned difficult and complex things such as thinking, talking or walking without any pedagogy, without any teacher and without any educator. We learn those complex activities ourselves – but of course in interaction with others, with people that are talking and walking and thinking. This is the principle that we apply. We learn with people doing the kind of things that we want to learn, and we are learning together, all the time. This is how we learn with others, in interaction with others, and basically learning is changing your relation with the others. And, of course, we learn with the Zapatistas, and then I will elaborate a little around this, because Mexico is today a disaster area. It is a horror! As you perhaps know, we are today the most violent country on Earth, worse than Syria that has had a civil war for many years. The five most violent cities on Earth are in Mexico, with an amazing level of inequality. We produce some of the richest men on earth, and some of the poorest people. We have many people, more than half of the people in Mexico, classified as in extreme poverty. We are suffering from all kinds of violence in a very patriarchal, racist and sexist society.

And then we are dealing with another horror – which is of course not only affecting Mexico, but the whole world. The Guardian was right when they stopped using the term “Climate Change” and instead they said that we are facing a “collapse”. And yes, we are in a collapse, we no longer have the climate we used to have, and we don’t know anything about the new climate, and we don’t know if it is compatible or not with human life – and the social, political collapse is even worse. This means that all the institutions that we established to govern us, are today in a state of final collapse and are falling apart. This is very clear looking at the situation in Mexico. We are living in that final collapse, with the old idea of climate, and with the old idea of a socio-political system – with the economy, and the public policies, and institutions, and all different aspects. At the same time, we have perhaps, because of this, some of the most beautiful experiences – of a new world that is emerging in the womb of the old. One way to describe this is that when we started Unitierra, more than twenty years ago, we discovered some fantastic experiences from collective communities that, beyond the Zapatistas, were challenging the dominant regime, and that were trying to follow an alternative plan and that alternative path. This was foremost an anti-patriarchal path. This implied basically two things: suppressing and eliminating all hierarchies, and putting life and caring for life at the very centre of the social organization.

The second principle was to look for sufficiency, the principle of sufficiency instead of the premise of scarcity. The premise of scarcity, in the economic society, implies basically that you assume that the ends are unlimited, but your means are limited. And then you need to solve the question of the allocation of resources, how to allocate those limited means to unlimited ends, and then you have the economic problem, and you have the economic society. We find that assumption foolish, or immoral, and then we assume that we have ends according to our means, and that they are proportionate to our means – and then we are looking to have enough to live a good life, in our own definition of what a good life is.

The third principle that we adopt is autonomy. Autonomy in every aspect. Autonomy for eating, learning, dwelling and for every aspect of our life, we are constructing autonomy. To give an example, the application of a principle – that is a Zapatistas principle: in Unitierra there are not only the people that come here to learn something with us and our friends, but there are people that want to “work” for us. But because we are trying to avoid work, to abolish work, work meaning all the activities that you need to do because you have a job, because you need to produce something to get some money, etc. Then the people that are coming to Unitierra to work, define what they like the most. What kind of activity gives them joy and excitement, and they can start doing that, they decide how much time they will dedicate to that activity. And then at the end of the month they present a receipt to collect the money they need for their sustenance. No one is hiring them, and they don’t have a boss. They are really free and trying to joyfully do what they like to do. And they are doing this for Unitierra, and for the activities and commitments that Unitierra has for these communities of Oaxaca.

This is more or less the same principles that we learnt from the Escuelita among the Zapatistas. This is life in the communities. And then what you have in Oaxaca, with the Zapatistas in different parts of Mexico, is people living just for their survival, just to be able to live in the midst of the horror of the collapse of everything; they are creating a whole new way of doing things, living and constructing and dwelling and doing everything.

Because we were doing this kind of exercise, we discovered some friends in India that were doing something similar. And then, together with Ashish Kothari, Shrishtee Bajpai and others, in May 2018 we created what we called the Global Tapestry of Alternatives (GTA) [1]. We wanted to weave together different kinds of alternatives that are anti-patriarchal, anti-capitalist, anti-democratic, etc.

Magnus Ericson: All these actions or activities seem to be based on sharing and on hospitality. As I’ve understood it, there are different Unitierras, and they’re all functioning based on the different context and conditions, on different local issues and needs?

Gustavo Esteva: This is for us a very, very important point. And I think this can be of interest for you. First, we started and we decided to keep the notion of scale, we must not grow too much. We must keep a human scale, we should be small. And then because people were interested in Unitierra, we invited them to create their own Unitierras. It is not a brand, it’s not a system. They are inspired by what we are doing, and then they create community-Unitierras, there are several Unitierra communities in Oaxaca. There are other Unitierras in other states of Mexico, such as Chiapas or Puebla, there are Unitierras in the United States in the Bay Area in California, in Toronto in Canada, there are two in Colombia, there is one in Catalonia in Spain, there’s one in Japan. Everyone is autonomous and independent, following their own paths.

For us, it is very important, first, the principle of scale. The notion of sense of proportion to keep this at a human scale; but second to be rooted, to be localized. For us, this idea of the concrete space in which you live, to which you need to adapt – that is for us a fundamental importance. It is not adopting an abstract universal principle or Utopia, but adapting to each context. Also, the Zapatistas at the time said: “please don’t imitate us, try to organize yourself in your own way, in your own context, it should be completely different to try to organize your life in Mexico City than in the Lacandon Jungle in Chiapas”. They are not presenting a model of how to live, how to do things. They are inviting people to follow their own inspiration, their own context and their own localization. It is really a very, very important point for us.

And I think that the virus, COVID-19, is perhaps teaching the whole world that specific lesson. We have now, as you may know, The World Localisation Day [2] on June 21st. All over the world they will celebrate the importance of being rooted, or being at your place, or trying to localize yourself and to find yourself not running from one place to the other, and being an abstract resident, but instead trying to inhabit your place, to create your own place, to shape your own place in a certain way.

Magnus Ericson: And all these strategies that come from the indigenous people that have been operating locally, I think, really show the clash between modernity and these New Worlds.

Gustavo Esteva: Yes, it’s called New Worlds or New Societies, and it is really a different kind of relation with the earth, with others, learning from others, having a mutual learning with the rocks and the animals and the plants and the people. Having a really different kind of relation with Mother Earth, and with other humans. Yes, it’s a different attitude, a different moral and attitude, and I think this is precisely the time for this.

We needed it. In a very real sense, we are saying that this current moment, these terrible moments in which we are living today – and it’s a moment of danger of course – not only because of the virus, but because of the authoritarian moves that we are experiencing all over the planet, and in a drive towards a society of control. Then we are saying that the main battle will be waged in the stomach, that depending on what we do with the stomach, we will have different outcomes. People learn it because of confinement, because of the virus, to have to stay at home and to be fed by the system. They are calling Uber eats, or someone bringing food to their homes, and in many cases, cooked food, already prepared food. The restaurants survived through producing food that is ready to take with you, or to bring to your home. And then there were people who learned how to be fed by the system, and to be fully dependent on the system to be fed. And if that principle wins, if people adopt that pattern, then we will see the final destruction of the planet, then agribusiness will really destroy the planet and the planet will produce more pandemics, every year, and we will have the end of the world, as we know it very, very soon. The path of destruction can be accelerated because of this.

But I hope – this is my hope; what I am seeing is something radically different. People are discovering that they need to produce, and through the principles of Via Campesina. This is the biggest organization in the history of humankind. Hundreds of millions of peasants together, and what they say is that you need to define, by yourself, what you will eat, and then to produce this yourself. And this is exactly what is happening. First of all, it’s mainly small producers, mainly women, who are feeding 70% of the people on earth. This means that agribusiness, which controls more than 60 percent of the food resources on Earth, are only feeding thirty percent of the people. They are destroying the planet for only these thirty percent. Then beyond that, many people started to produce food at home.

This started in many different ways: one very famous case started in Cuba during the special period when the Soviet Union vanished, and they had no money to buy their food. They discovered that after fifty years of revolution they were importing seventy percent of the food, and they had a very industrialized agriculture and they had no dollars to import fertilizers or chemicals. And then there was hunger in Cuba, and people started to produce food at home in the small spaces they had. And today in Havana, they are producing sixty percent of what they eat in Havana. This shows the potential of urban production of food and many people are doing that everywhere. We have spectacular cases in the United States, for example, about how to produce food at home in the cities. During COVID-19, this has been an explosion. Suddenly in many states of the United States, seeds disappeared because people were buying like mad, to cultivate food at home. There are some stories that illustrate the point: in New York there was a sudden lack of yeast when people started to produce their own bread. Thousands of families started to make bread at home again – they had this tradition, but they stopped doing that. And when they started because of COVID-19, there wasn’t any yeast to be found in New York… I have many stories of this kind, meaning everywhere people are really trying to produce their own food.

Urban agriculture workshop with Edgardo Leonel García García. Still from Re-learning Hope: A Story of Unitierra, a film by Udi Mandel and Kelly Teamey

Dry toilet workshop with Cécar Añorve. Still from Re-learning Hope: A Story of Unitierra, a film by Udi Mandel and Kelly Teamey

And this creates a different relation with the world, and different relation with others. We are saying that if you produce your own tomatoes, you can produce reactionary tomatoes or revolutionary tomatoes, because if you are doing it just because it is the fashion, it’s just for you and you are buying the seeds and the chemicals, etc., then they are reactionary tomatoes. But if the tomatoes are the seeds of community – if you are exchanging seeds and the tomatoes and you are creating something like commons in the city, then those are revolutionary tomatoes! You are creating something different.

Magnus Ericson: I wanted to ask you more in detail about what kind of issues you’re dealing with within Unitierra, in Oaxaca and how. If you could give some examples. I’m also interested in how this idea of the commons and how a space like Unitierra could also be a way of sharing ideas about the commons?

Gustavo Esteva: Yes, of course it is a place like a common. We are creating commons, all of us connected with Unitierra, and we’re doing different activities. We have had weekly open conversations. Every Wednesday we meet at four o’clock, and then we have an open conversation, for twenty years now, and this has been an opportunity to learn from many, many people from many, many different parts that come together. Now we are coming together in a virtual way because it hasn’t been possible to be together in one place. And this is one way of learning. Of course, in a basic way we are sharing, which is our way to learn in freedom, but we’re also sharing different ways of creating autonomy and living with sufficiency – and we have created autonomy in eating, and healing, and dwelling, and playing, and everything – all different aspects of daily life. And just to give you an example: one of our basic principles of Unitierra, and of our commons, is to have interculturality, the full recognition, to be hospitable to the otherness of the other, and to practice what we call the intercultural dialogue. Then we are all the time in the beautiful, virtual challenge of interacting with others, with people of different cultures, not only the 16 different ethnic groups of Oaxaca, but people coming from other countries, from other cultures to visit us.

I can give you a very concrete example of what we are doing right now. Most indigenous communities of Oaxaca don’t have medical services, and they have been basically abandoned by the system. During COVID-19, they have not been offered any support and they are victims of the dissemination of all kinds of confusion and misinformation. In the communities, we now have opposite convictions, you have some people that say, no, no, this is an invention of the government, the virus does not exist, and they are completely ignoring it. Other people who are living in terror are really afraid of the information that is spreading. We are working with them, with the communities with whom we have close relations with, and we are creating a kind of experiment, juxtaposing different kinds of medical traditions, allopathic, homeopathic, Ayurveda, and the traditional ways of healing in their communities with the healers and the Midwives etc. trying to create different attitudes for prevention, and different attitudes for treatment of the virus. And then we are working with all of them with different attitudes, with a campaign that we call “against fear – hope”, then we are trying to nourish hope with examples and practices, and we’re using radio and many other ways to disseminate the best information available, the basic information about the virus and experiences about what to do, how to react before the virus and after the battle. This is the kind of thing that we do in our practice.

Pelin Tan: I’m just curious, and this may be a last question: this knowledge and practice of indigenous communities, their relation with Earth, their relation with nature and so on, I think this is today an example of a kind of “resistance knowledge” or “heritage knowledge”. You talked a little bit about that, but I would like to know more. I mean, for example, what is the role of elderly people in such collective learning and unlearning situations, and what is the role of women here?

Gustavo Esteva: Let’s start with the last part, that for us is a very critical, very important part of our experience. In the indigenous communities, their combination of all patriarchal traditions with modern sexism created something like hell for women. Many women, living and experiencing that kind of hell, were forced to take steps forward, and started to lead social change. Something happened in such a spectacular way, that we started to talk about the feminization of politics. Because they were living in a completely different way than men, and doing something very different.

This evolved to March 8th, when they had this magnificent march where they basically said that they would dismantle the normalization of patriarchy. No more patriarchy would be accepted as a normal way of being, or as a normal state of things. And then what we are now discovering – something that is really at the very centre of Unitierra, and in our daily life – which is to follow the inspiration of women that are creating a different attitude about everything. And with them, we put life at the centre, really caring for life and abandoning the patriarchal obsession, the patriarchal prejudice that human creations are better than natural creations. The perhaps most well-known example is that we can destroy native seeds, and replace them with artificial seeds produced in labs, with GMO etc., etc. – destroying the planet and destroying native seeds because of the idea that human creations are better. But we are abandoning these principles because of the women, because of the lessons given to us by women.

And yes, one of the main points that women are bringing to us, is how modern society has abandoned the old people. It is assumed that they are these impossible human beings, because they are no longer productive, and they put them in horrible nursing homes, expelling them from daily life and condemning them to a very miserable life. But the women are telling us how important it is for the communities to respect the elders, and listen to them. I can even express this in a very personal way: my partner, my “compañera” Nicole and I, are in the council of elders of Unitierra, and we are saying that an elder should be a person that should be respected and listened to, but you don’t necessarily need to do what they say. In Unitierra, sometimes they ask us for our opinion, sometimes they do what we say and sometimes they don’t. This means that it is not associated with power, but it is about listening to someone, to respect their experience and to know that this is the way in which culture has been transmitted from one generation to the next. We really try to care for old people, to respect them and to give them a very special place in the communities. This is of course very, very important in the indigenous communities. They have not abandoned their elders, they have a deep respect for their elders, and whenever something important happens, they go to the elders to ask for their opinion. They are not seen as the bosses, but the people with respect in their communities – and yes of course they have this relation with Mother Earth too, which we abandoned in modern society.

For us, it has been fundamental to “de-learn” what we are. We were educated in a certain way, with the idea that we are individuals – and we are not. We can learn from the indigenous peoples that we are knots in nets of relations and that every I is a we, and then we can see that we are alive and flourishing in all their communities. We are trying to learn how to reconstruct ourselves as “wes”, creating commons in the cities, creating also something for those people who are fully individualized and who don’t have anything that he or she can call community behind them. We are showing that through friendship, we can recreate the commons – friendship is the stuff that can help us. It’s not an ideology, it’s not a doctrine, it’s not a project – it is friendship. This gratuity of friendship is the stuff that can create the possibility of new commons in the modern cities.

This conversation took place online between Oaxaca, Mardin and Stockholm, 17th June 2020, then transcribed and edited.

1.

Global Tapestry of Alternatives www.globaltapestryofalternatives.org

2.

World Localization Day www.localfutures.org/events-calendar/other-past-events/world-localization-day-june-21-2020/

was an independent writer and grassroots activist. He has been a central figure in a wide range of Mexican, Latin American, and international nongovernmental organizations and solidarity networks, including Universidad de la Tierra en Oaxaca. In 1996, he was an advisor to the Zapatistas in their negotiations with the Mexican government. A prolific writer, he is the author of more than 40 books, published in seven languages. He has also written hundreds of essays. He is a columnist in Mexico’s leading daily, La Jornada, and writes occasionally for The Guardian. Among his academic honors: an Honorary Doctorate (Honoris Causa), the National Award for Political Economy, and the National Award for Journalism. has served as president of the Mexican Society of Planning and the 5th World Congress on Rural Sociology and Chairman of the Board for the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development. Gustavo Esteva passed away in March 2022.

is a Project Manager at IASPIS, responsible for the design, crafts and architecture related programme. He has a background as curator, project coordinator and educator. Between 2014 and 2018 he developed and managed two experimental postgraduate courses on socially-engaged critical practice; Sites and Situations and Organising Discourse, at Konstfack University College of Arts, Crafts and Design, Stockholm. Between 2009 and 2014 Magnus Ericson was a Senior Advisor/Coordinator and Curator for a new design-related programme at Arkdes, Sweden´s National Center for Architecture and Design, in Stockholm. Between 2007 and 2009 he was assigned as a Project Manager at IASPIS to pursue and develop the activities within the fields of design, crafts and architecture. Together with Ramia Maze he was the author and co-editor of DESIGN ACT Socially and politically engaged design today – critical roles and emerging tactics (Berlin, Sternberg Press 2011).

is the 6th recipient of the Keith Haring Art and Activism and fellow of Bard College of the Human Rights Program and Center for Curatorial Studies, NY, 2019-2020. She is a sociologist, art historian and currently Professor, Fine Arts Faculty, Batman University, Turkey. Tan is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Arts, Design and Social Research, Boston; and researcher at the Architecture Faculty, University of Thessaly, Volos (2020-2025). She is the co-curator of the Cosmological Gardens project by CAD+SR and she was the curator of the Gardentopia project of Matera ECC 2019. Tan, was a Postdoctoral fellow on Artistic Research at ACT Program, MIT 2011; and a Phd scholar of DAAD Art History, at Humboldt Berlin University, 2006. Her field research was supported by The Japan Foundation, 2011; Hong Kong Design Trust, 2016, CAD+SR 2019. She was a guest professor at Ashkal Alwan, Beirut 2021; Visiting Professor at School of Design, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, 2016 and at the Department of Architecture, University of Cyprus, 2018. Between 2013 and 2017 she was an Associate Professor of the Architecture Faculty at Mardin Artuklu University. She is a member of Imece refugee Solidarity Association and co-founder of Imece Academy; advisor of The Silent University and the pedagogical consortium of Dheisheh Palestinian Refugee Camp, Palestine. In 2008 she was an IASPIS grantholder.

Unitierra website: https://unitierraoax.org/english

Re-learning Hope: A Story of Unitierra, a film by Udi Mandel and Kelly Teamey: https://vimeo.com/172681670