Learning decolonization, unlearning architecture

Andrew Herscher and Ana María León

CATEGORY

“Histories of modern architecture vividly participate in the relegation of Indigenous peoples to ahistorical temporality. Most vividly, perhaps, these histories do this by simply not contending with Indigeneity in the constructions of modernity they narrate.“

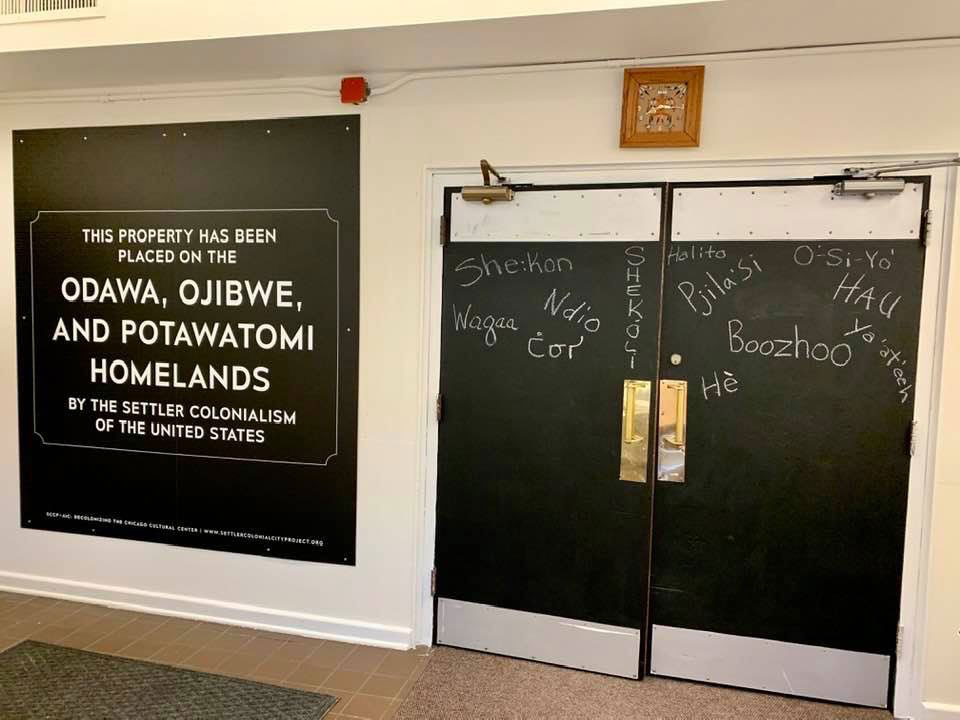

Decolonization and Indigenization: “This property” installation by SCCP for the Chicago Cultural Center relocated to the American Indian Center, Chicago, and subsequent annotation in Indigenous languages by members of the American Indian Center on neighboring doors. Photo: courtesy of Heather Miller, 2020.

Amidst all the relationships it avows to politics, history, culture, social issues, technology, and much else besides, architecture has been and remains enmeshed with colonialism. In early stages of settler and extractive colonialism, architecture was directly involved in the seizure, settlement, and exploitation of Indigenous land, along with the enforced and enslaved labor that cultivated and built on that land. And today, architecture remains indebted to colonial legacies through the property it occupies, the capital it is financed by, the materials it is constructed from, the underpaid migrant labor that continues to construct it, and the expertise that benefits from it through accumulations of social and financial capital. Anibal Quijano has vividly described the ways in which colonial logics, practices, and relations persist through a “coloniality of power” that outlives formal colonial regimes; examined against its grain, architecture across the globe is both an instrument and product of this coloniality.[1]

Consider, for example, unlearning the history of architecture. In received versions, these histories are structured by an absence of attention to colonialism, Indigeneity, and slavery. Before attending to these absences, however, it is worth considering their necessity in the light of their destabilizing presence—a presence that would reveal the colonizing dimensions both of architecture and its histories. These histories reserve historical agency for colonizers; if they do not ignore Indigeneity, then they almost always deploy it as a mere foil for colonial modernity, with Indigenous people posed as inhabitants of a timeless and unchanging nature that, depending on the narrative, colonizing modernities either improve or annihilate. As Jean O’Brien has written in her landmark book on this process, Firsting and Lasting, “Indians reside in an ahistorical temporality in which they can only be the victims of change, not active subjects in the making of change”—a subjectivity that colonialism reserves for white colonists and those assimilated into whiteness.[2]

Histories of modern architecture vividly participate in the relegation of Indigenous peoples to ahistorical temporality. Most vividly, perhaps, these histories do this by simply not contending with Indigeneity in the constructions of modernity they narrate. At the same time, these histories displace the role of racial capital and racialized labor as extraneous to architecture discourse and dismiss the role of enforced, displaced or migrant labor whose status is based on their adjacency to whiteness. This labor, in turn Black, Asian, and from Indigenous and mestizo groups in the Americas, has been structured by the displacement of Indigenous peoples deprived of their claims to land in other parts of the world.

Oriented instead around questions of aesthetic form, social function, authorial intention, technology, and political meaning and consequence, typical histories of modern architecture, like typical practices of contemporary architecture, do not engage Indigeneity, whether it is with respect to issues around land, labor, historiography, environmental epistemologies, or relations of human and non-human life. Think, for example, of the construction of canons, the notion of architectural autonomy, the discourse of modern planning, and other Eurocentric projects that elide the role of colonialism and white supremacy in their formation.[3] While at least registering the collaboration between modern architecture and colonialism as a theme, recent attempts at making the curriculum of architectural history more diverse, equitable, or inclusive also serve to advance colonial and colonizing histories by splicing “case studies” or “themes” into analytical categories and historical temporalities that are sedimented in colonialism.

Consider, too, unlearning architecture in design studio courses—courses in which notions of property and authorship underlie the discipline’s colonial mores. Ideas of “excellence,” in the studio as in the wider world, set parameters of worth established by the colonizer —from professional dialects, through cultural references, to access to the wealth that enables the cultivation of excellence in the first place. Supposedly universal standards of excellence center whiteness and white adjacency over positions based on a rejection of or lack of access to the wages of whiteness. Moreover, when studios engage “other,” “marginal,” “hidden,” “omitted,” or “different” peoples, histories, or epistemologies, this engagement often operates as a prophylactic inoculation, including the excluded in order to mark it as secondary, derivative, or not worthy of sustained disciplinary attention.

Consider, finally, unlearning the institutional reaction to architecture students who, after the murder of George Floyd, began to call out the anti-black racism and colonialism embedded in their courses, curriculums, student bodies, faculty composition, and relationships with surrounding communities. Many institutions responded to these calls with a series of quick fixes—gestures that were insufficient, ephemeral, and that prioritized gestures of solidarity over meaningful structural change. These quick fixes included an increase in Black, Indigenous, Asian, and Latin American scholars (conflated, not unproblematically, under the term BIPOC) invited for talks and short-lived adjunct positions, along with prominent features of students belonging to these groups on websites and other spaces of institutional appearance. [4]

The most widely-adopted quick fixes are oriented around initiatives promoting DEI—diversity, equity, and inclusion—as is the case at our own institution, the University of Michigan. [5] Urgent calls are being made, especially by students, for architectural curriculum to be “decolonized” and “anti-racist.” At the same time, administrations of schools of architecture are conflating “decolonization” and “antiracism” within pre-existing DEI plans, projects, and bureaucracies—conflations that allow white-run and colonially-based institutions to incorporate the appearance of change without changing their power structure, relationships with the land, and relationships with Indigenous and other non-white communities. This incorporation disempowers and depoliticizes both decolonizing and anti-racist projects—projects that are often in tension, and even sometimes in contradiction with one another. [6] Rather than subsume these frictions under the banner of depoliticized inclusion, academia can provide the space to discuss and understand these differences.

In the context of a settler colonial state such as the United States, we have learned from Indigenous communities and the Indigenous radical tradition that decolonization is first and foremost a political project: a rematriation of land to Indigeneity and the constitution of right relations with the land’s constituent parts. In the context of a racial state such as the United States, we have learned from Black communities and the Black radical tradition that the project of antiracism is also a political project: action against racism, and in particular anti-black racism, as well as the structures that promote and foster it. These projects are not always aligned: Scholars of the Black Atlantic, for instance, have theorized the connection to land of enslaved African populations deprived of their own Indigeneity and posed anti-blackness as constitutive of settler colonialism. Claims for reparations for Black populations may seem to run counter to Indigenous claims to land.

A third term, co-liberation, is helpful in understanding the common path shared by decolonial and anti-racist work. Co-liberation is based on the certainty that colonialism and racism dehumanize both those who are oppressed and those who are privileged, as those privileges require the oppression of others. The path towards co-liberation might begin with the acknowledgement of these dehumanizations and the histories of subjugation they are part of, but also prompt concrete action—actions towards unlearning architecture, learning decolonization, and placing ourselves in new relations with one another and with the land.

Unlearning architecture and learning decolonization require the transformation of architectural pedagogy. A decolonizing architectural pedagogy necessarily upends the discipline’s reliance on property; on authorship and claims to genius; on auratized works and claims of formal distinction; on racialized, underpaid, or still in many cases enslaved labor; on unacknowledged differentiations based on race, class, gender, and body ability. Decolonizing the discipline entails challenging academia’s reliance on settler colonialism, white supremacy, and patriarchal frameworks, as well as understanding the entanglements of those frameworks with one another. Finally, decolonizing the discipline necessitates betraying its own disciplinarity, its reliance on expertise, and its isolation from or savior relationship to the populations it claims to serve. A decolonized pedagogy might turn instead to the built environment and the myriad ways in which people house themselves on the earth; a recognition of the many forms of labor involved in the production of the built environment; and an honoring of the investments of care, time, and materials required of this labor.

We live and labor in a colonizing, racist, and capitalist world; attempts at decolonization might seem at once urgently needed but also unreachable and utopian. This dilemma easily resolves into impulses to give up on or rationalize the impossibility of decolonization or avoid action for fear of acting improperly. But colonialism depends on and thrives upon these impulses. Could we be mindful and careful in our actions without veering into hesitation, neutrality, and paralyzing positions that render us complicit with the violence of colonizing white supremacy? Could we push against the colonizing, racializing, and extractive forces at the root of architecture to teach, learn, and build another architecture for another world?

This text has been commissioned and written uniquely for Urgent Pedagogies.

1.

Anibal Quijano, “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America” in Nepantla: Views from South, Vol. 1, Issue 3 (2000): 533-580. Walter Mignolo and other Latin American scholars known as the Modernity/Coloniality group have elaborated on these topics, including Ramón Grosfoguel, Arturo Escobar, Fernando Coronil, Javier Sanjinés, Enrique Dussel, and others. Indigenous scholars from the Americas have criticized the group’s European roots and adjacency to US academia. See Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, “Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: A Reflection on the Practices and Discourses of Decolonization,” South Atlantic Quarterly (2011), 111(1): 95-109.

2.

Jean O’Brien, Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 105; see also Eric Wolf, Europe and the People Without History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982).

3.

Scholarly discourse denouncing these complicities has long been present in the groups left out of these histories, including Indigenous groups, postcolonial scholars, the Modernity/Coloniality group in Latin America, scholars of critical race theory, and others. Architectural discourse’s late engagement with the work of these groups only points to the particular complicities of the discipline with the very processes they push against.

4.

These groups are often conflated under the term BIPOC which refers to Black, Indigenous, and people of color and means to encompass non-white populations. Scholars have raised concerns over the use of this term; some of the arguments include the centering of whiteness and the importance to name cultural groups specifically. This naming, however, becomes challenging when addressing the complications of multiple overlapping identities. One of the challenges of this term is that it rises in reaction to the racism prompted by whiteness, and in rejecting whiteness it needs to necessarily address it.

5.

This approach is exemplified by the University of Michigan. In his recent book, Undermining Racial Justice, Matthew Johnson has elaborated on how Michigan was eager to address the demands of black activism on campus without disrupting institutional priorities, making racial inclusion compatible with inequality. See Johnson, Undermining Racial Justice: How One University Embraced Inclusion and Inequality (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2020).

6.

See, for instance, Frank B. Wilderson III’s critique to the so-called settler-native-slave triad and the critiques leveraged to the foundational essay by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is not a Metaphor,” by Tapji Garba and Sara-Maria Sorentino, as well as Tiffany Lethabo King. Frank B. Wilderson, “R & Ghosts: The Performative Limits of African Freedom.” Theatre Survey 50, no. 1 (May 2009): 119–25, https://doi.org/10.1017/S004055740900009X; Tapji Garba and Sara-Maria Sorentino, “Slavery is a Metaphor: A Critical Commentary on Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang’s ‘Decolonization is not a Metaphor’” in Antipode 52, Issue 3 (May 2020). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/anti.12615; Tiffany King, “Labor’s Aphasia: Towards Antiblackness as Constitutive of Settler Colonialism” in Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society (10 June 2014) https://decolonization.wordpress.com/2014/06/10/labors-aphasia-toward-antiblackness-as-constitutive-to-settler-colonialism/

endeavors to bring research on architecture and cities to bear on struggles for rights, justice, and democracy across a range of global sites. He is co-founding member of a series of militant research collaboratives including the We the People of Detroit Community Research Collective, Detroit Resists, and the Settler Colonial City Project; he is also co-founder of the Decolonizing Pedagogies Workshop at the University of Michigan, where he teaches. Among his books are Violence Taking Place: The Architecture of the Kosovo Conflict (Stanford University Press, 2010), The Unreal Estate Guide to Detroit (University of Michigan Press, 2012), Displacements: Architecture and Refugee (Sternberg Press, 2017), and The Global Shelter Imaginary: Ikea Humanitarianism and Rightless Relief, co-authored with Daniel Bertrand Monk (University of Minnesota Press, forthcoming).

is an architect and a historian of objects, buildings, and landscapes. Her work studies how spatial practices of power and resistance shape the modernity of the Americas. León teaches at the University of Michigan and is co-founder of several collaborations laboring to broaden the reach of architectural history including the Decolonizing Pedagogies Workshop, Nuestro Norte es el Sur, and the Settler Colonial City Project. She has co-organized several teacher-to-teacher workshops exploring architectural history’s relationship to intersectional feminism, the global, the South, decolonization, and antiracism. Her book, Modernity for the Masses: Antonio Bonet’s Dreams for Buenos Aires, was recently published by the University of Texas Press.