Inside/outside/across/between: Crossing thresholds, academically and otherwise

Katrine Dirckinck-Holmfeld and Isabelle Massu, convened by Dalida María Benfield

CATEGORY

With Isabelle Massu and Katrine Dirckinck-Holmfeld, Dalida María Benfield engages in a roundtable, ”Inside/Outside/Across/Between: Crossing Thresholds, Academically and Otherwise,” regarding the perils of the practices of liberatory pedagogies in two art academies in Europe. The feminist and decolonial research, artistic practices, and pedagogies of each collide with patriarchy and entrenched colonialities.

Their testimonials about testing the limits of their academies reveal the urgency of the epistemic, political, and pedagogical work to be done to create spaces of relative freedom from oppressive academic legacies, curricular architectures, and practices.

Dalida: Thanks to you both for this conversation on a question that is urgent, now. It is about the academy – being inside or outside, or across, or in between. It’s very interesting how it comes up, not only for me, but for almost everyone who has been involved with the work of the Center for Arts, Design, and Social Research (CAD+SR). It’s obviously relevant for Urgent Pedagogies, Issue #5: Pluriversality: Where can they occur? Where do we position ourselves to address urgent questions? And also, what are the urgent issues in the academy that need to be addressed? Further, what urgent questions can or cannot be addressed within the academy? I really wanted to have this conversation with the two of you, because of your recent experiences, to add further turbulence to our discussion. We need to interrogate this edge. We’re hoping to open that space of consideration, amongst others, with our issue.

Katrine: I prepared a small presentation on the reasons why I’m outside of the academy, and also in relation to the question that you posed to us earlier via email, Dalida: “What are the problems that it presents to our pedagogies and practices?” I thought bringing my own case into the discussion might be a good catalyst.

Isa: Then maybe it would be interesting for me to give the background on my situation. It’s impossible not to talk about that – the reason why we are in this situation – considering the question. We are joined by the problem with academia, but in different contexts.

Dalida: Katrine, that’s so generous of you. It would be wonderful if you started. Then, we can begin to have the conversation, and move to speaking about your situation, Isa.

Katrine: Now, in Denmark, there’s a lot of backlash against research within the fields of feminist-, queer-, gender-, decolonial-, post-colonial-, migration- studies and artistic research. And at the same time, there are a lot of cuts and austerity measures at the universities. So, I locate the conversation about my situation within this specific environment, but I think it’s also very much present in many other contexts worldwide. I’m a visual artist and a researcher and until last year, exactly, I was the head of the Institute for Art, Writing and Research at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts where I was also in a post-doctoral position. My postdoctoral research project was exploring the colonial history of the Art Academy and I was teaching a course, “Min(d)ing the Academy,” exploring the material remnants of coloniality within the building of the art academy. So, I titled my presentation for today “Teaching to Transgress: Education as a Practice of Freedom”, which of course, is inspired by bell hooks’ book of the same title, but I add: “But Not Too Much!? [1]” And that’s the question I would like to propose for our conversation: Can there be too much teaching to transgress?

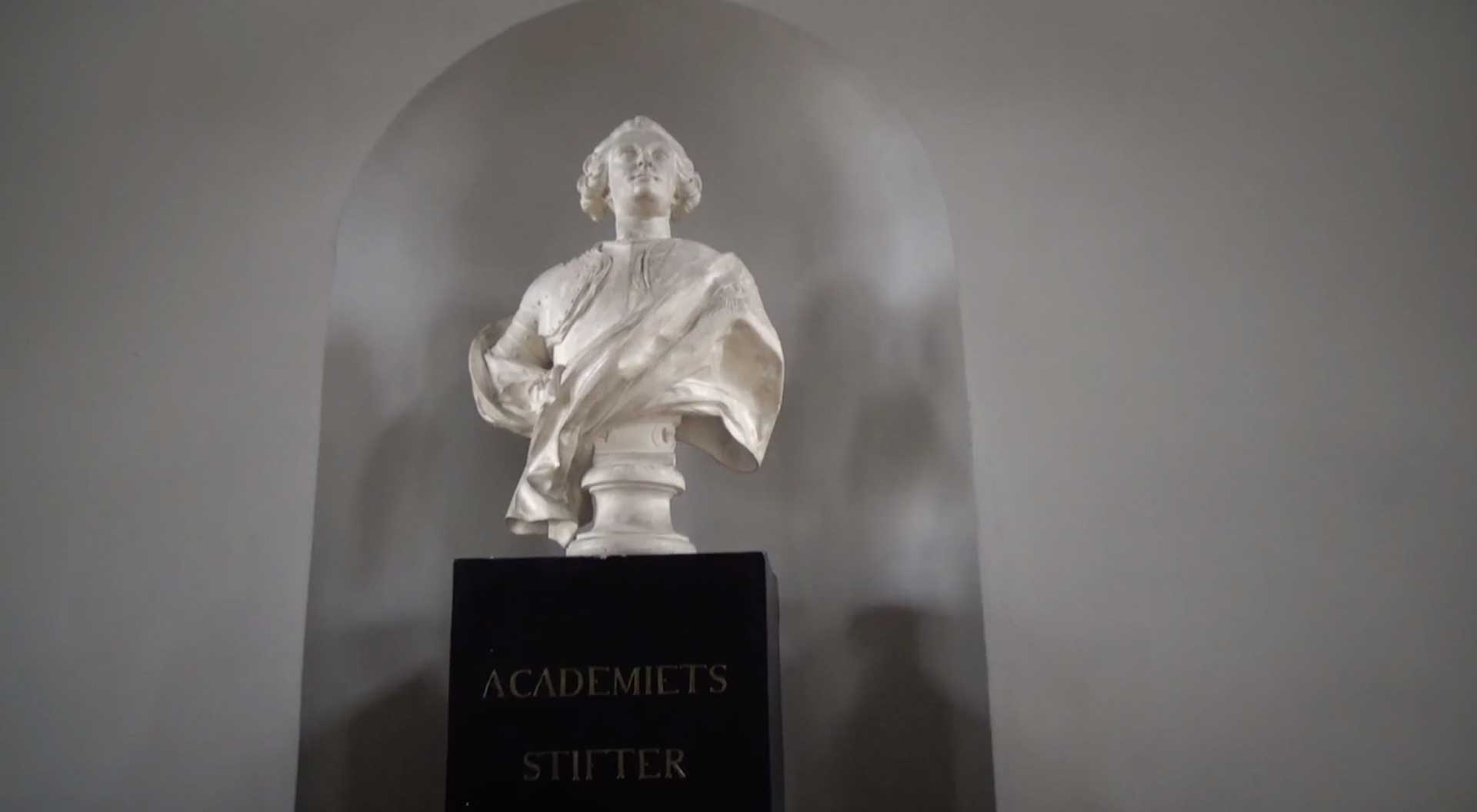

The reason why I am currently outside the academy was because of an artistic happening that took place at the Art Academy. The artists’ group Anonymous Artists removed a plaster cast copy bust of Frederik the Fifth – who was an absolute king, who incorporated the Danish-Norwegian plantation economy and the transatlantic enslavement trade, in 1754 under his absolute power, the same year that he founded the Academy of Fine Arts – from its pedestal in the assembly hall of the Art Academy and submerged it in Copenhagen Harbor.

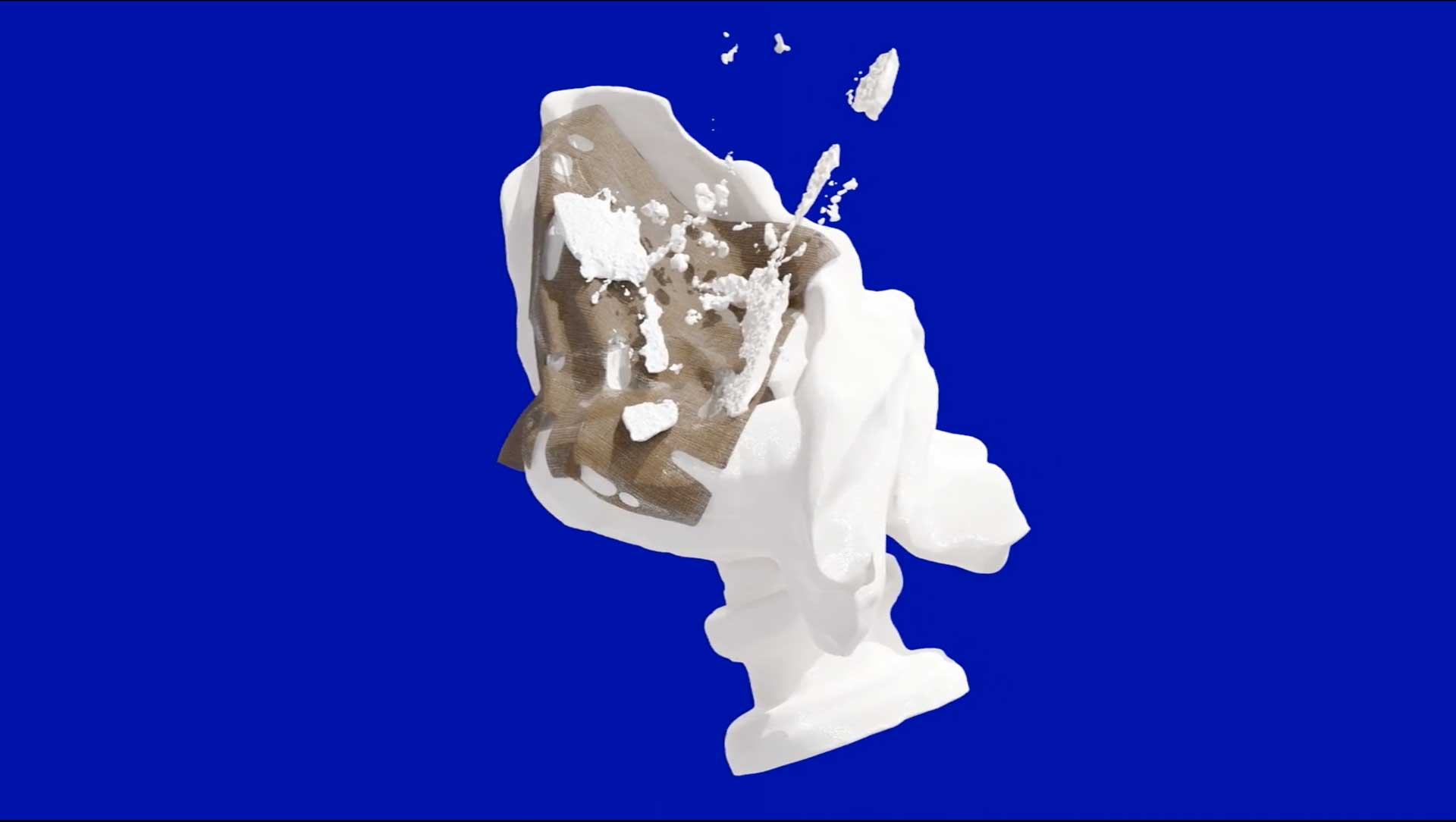

Still from video, Anonymous Artists. 2020.

Before being removed from its pedestal, it had been installed in the back of the assembly hall. The copy-bust was like an overseer, overlooking the educational activities that took place in the assembly hall, looking over the shoulders of the students and other participants who would come to the Art Academy. The artists’ group, Anonymous Artists, took it off its pedestal in the back of the assembly hall and moved it to the Harbor Front of Copenhagen, which was also an infrastructure for the colonial trade. There, it was given back to the elements. It was submerged in Copenhagen Harbor. This peaceful and spontaneous artistic happening created a major fuss and outcry in the media, where it was condemned by right wing politicians and the right-wing media. But it was not only the far right but also the Social Democrats, and different politicians, but also artists and members of the cultural elite. Some prominent artists went out and compared the happening to ISIS and Taliban and demanded the jailing of the art activists. And police and journalists went on campus to apprehend the art activists. I decided to take the responsibility for the artistic happening and was immediately expelled from my position and the course I was teaching on coloniality was stopped.

The happening took place in line with many of the other Black Lives Matter demonstrations that we have seen worldwide. The hope was to create a discussion around how colonial legacies are still present within the art institutions and art education in Denmark today, and to put a focus on minoritized students and artists’ situations within these structures. A press release was distributed alongside video documentation of the artistic happening, stating that it was an act of solidarity with the people living in the aftermath of Danish colonialism in the US Virgin Islands, Greenland, India, Ghana and other places. In fact, the copy-bust was submerged just across the harbor from a statue called “Freedom” by the Ghanaian American artist Bright Bingpong. Bingpong dedicated this statue to the enslaved who fought for their freedom in the US Virgin Islands (USVI). The USVI are a former Danish colony (The Danish West Indies), and the USVI donated this statue to Denmark in 2016, on the occasion of “Transfer Day,” marking the centennial of Denmark’s sale of the islands to the US.

So, there’s a question that I would also like to pose, which is: What does education as a “practice of freedom” mean today (which is also the subtitle of bell hooks’ book)? It is quite an urgent question for me, but one which, of course, also has very different connotations depending on the different contexts and situations that we are in.

The bust that was submerged is a plaster copy of a bust, which exists in more than 25 copies in Danish museums and institutions. The Art Academy Council, who claimed ownership of it, has a bronze version in their collection. There were rumors spread in the media that this was a “priceless Danish statue” – the original bust created by Jacques François Joseph Saly, in the 1760s – which obviously it was not. It was a plaster cast copy which was created sometime between the 1950s and 1990s. And so, they sent out divers to dredge it up from the water. And then they stored it away, forbidding students and the public to get access to it. But then a group called the School of Re-membering – a student led initiative that emerged in the aftermath of the event – made the re-materialized bust into a souvenir object. The School of Re-membering has been selling these plaster cast copies of the re-materialized bust. So I think it’s also quite interesting how this white patriarchal form has been re-materialized or transformed into a newfound shape by giving it back to the elements, the water infrastructures of Copenhagen Harbor.

These are just some of the questions that I have been tussling with, in the aftermath of the artistic happening: Who counts as a subject? And who counts in a painting or as a portrait bust? Who are left to drown at the bottom of the sea? What is being dredged up, to be restored or cast anew? And then, and these two are actually your questions, Dalida: “What are the alternatives to colonial modernity and its temporalities? What technologies do we have, and which do we need to create?” I also ask, which do we need to abolish, and how can we fathom an abolitionist art education?

Dalida: Thank you so much, Katrine. There’s so much to think about alongside what you’ve just shared. Isa, do you want to talk about your location now?

Isabelle: Just to give you some background, I lived in the US for many years and I taught at the San Francisco Art Institute for two years, 2006-2008, which definitely opened up my vision about radical pedagogy. I came back to France with this approach to pedagogy in mind. I first started to teach at the Parsons School of Art in Paris, but the private system did not work for me. I am from a generation who still believes, naively, in the public system. I left Parsons for the Institut Supérieur des Beaux Arts de Besançon in 2013. Besançon is a medium sized city next to Switzerland. From the beginning, I started to witness a lot of dysfunction in the school. Neither colleagues nor the administration seemed to see it as a problem.

Before entering academia, I was interested in notions of self-knowledge instead of savoir (knowledge), experimenting in various contexts due to my desire to learn as I practice; learn as I travel and engage: learn as I love; learn as I live – continuing my daily education through a practice in the world, mostly within feminist associations and social centers. Probably starting on this route helped me create a space for understanding that each situation needs to be addressed differently; such as working in Algeria with women traumatized by the dark years of the nineties; or teaching at the dawn of the millenium open source software to feminists and queer women in Serbia; being taught by unemployed women how to build hardware, at a training center in Brussels while exchanging with them some other skills I had acquired; or helping migrant women to develop their presence on the net with self-employed businesses in the suburbs of Paris. All these moments in life offered me humility. But the arts was often missing. Poetry, images, and the beauty of a landscape without traces of war and violence. I have consistently navigated from one to another. Navigating from one to the other, when art was too comfortable or when politics was too hard to take. I had this completely naive idea that entering academia would resolve this duality. I believe the person who hired me in 2013 at Besançon saw in my hiring speech the premises of feminist pedagogy and the consecration of its own reputation during the emergent #MeToo era. He was a smart man making smart moves, but was deep down in the closet, and the school was a perfect setting (institution) to exercise his lost sexual power on young boys.

In 2018, some students were in danger, due to drugs and alcohol, through parties that he was, partly, organizing at the time. There were no rules, nothing, just a man getting older, clearly losing sexual power and trying to gain it back in some way. So, boys were rewarded, girls left on the side. A familiar situation that we all know so well. We had just seen Weinstein and DSK falling. But was it too early for him to believe this was going to happen? In his vessel? Holding on so tightly to such a natural inheritance? How to denounce? How to announce? How to have a say when the institution of the family was so tightly roped in? When some of the children protected the father and the holy ghost? When professors continued to exercise their predatory gaze, not foreseeing how #MeToo was becoming a magical force?

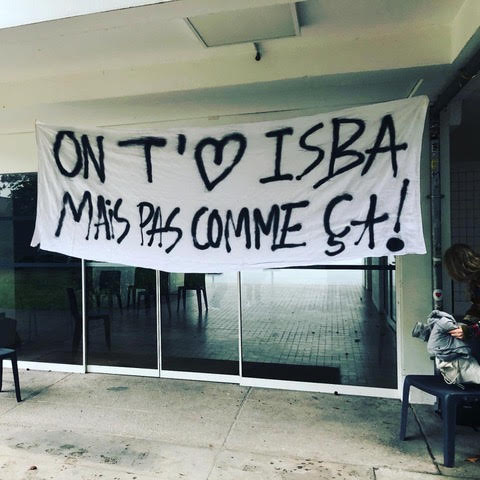

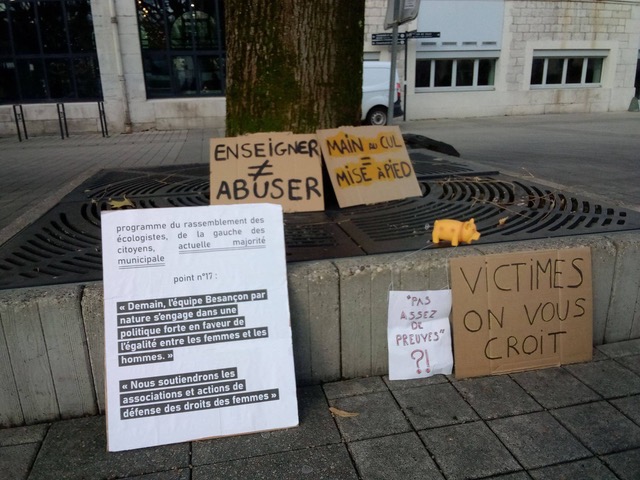

In the middle of that context, after 2018, once I started to expose behaviors, the question was, how to continue, witnessing everyday privilege and dysfunction, and remain in the institution. What could I do in the heart of the beast? Not long after this, with two other European schools, we built a program dedicated to feminist pedagogy, the “Teaching To Transgress Toolbox” [2]. And in 2020, well, last year exactly, finally, students of the school went on social networks and denounced all the harassment that had occurred in the past. All sorts of discrimination were called out. The students did an incredible job documenting stories, and on social media, adding next to each testimony a text of the law condemning the act or behavior. It just blew the school away. What was great about it was that it went viral and affected a lot of art schools in France. The whole art school network was on the spot. Then the director got fired in May of last year.

How could we, after all this, continue together? As I began thinking about the healing process, I thought of the institution in terms of family. Family as a metaphor for academia. I realized that we had protected the patriarch. The father, who dictates the rules of the institution. So, how was it the responsibility of the entire family? When there is abuse in a family, some members decide that what belongs to the family stays in the family, because, of course, there is privilege to gain, while others expose the abuse.

The city of Besançon sent us an association to work on conflict resolution, to talk about respect and good behavior in the workplace, but none of the questions were about the core of the problem. We never talked about abuse or privilege, which were really at the core of it all. What we really needed was to start family therapy!

Katrine: I think there’s many similarities with the “family” metaphor that you mention, Isabelle, and the Art Academy in Copenhagen. It is similar to a bourgeois family where there are a lot of public secrets and you are not allowed to reveal the secrets of the family, and if you do so it is a betrayal of the family. There were a lot of cases with #MeToo, racism, harassment and other forms of oppression, but there was no space to have a conversation or discussion around these issues. But it is interesting to discuss what measures were implemented to solve the problems, as you mention, Isabelle. In Copenhagen, the management also hired an external consultancy company because a group of students declared that they had lost their confidence in a professor. And there was another case, two years ago, with another professor, who was dismissed, after a group of students complained about sexual harassment and other forms of abuse. But we were never allowed to see the results of those investigations and the students were not allowed to gain access to their own testimonies.

On top of that, there was this idea that you could get a personal psychologist if you had a problem with this, instead of understanding it as a structural problem, which has existed since the creation of the Art Academy. It is founded on structural violence in terms of the patriarchal structure and colonial legacy. So instead of understanding the deeper structural implications, the problems became personalized and students felt isolated with their own experiences.

I think one of the differences was that in Copenhagen, after the happening took place by Anonymous Artists, the Art Academy opened its gates to the police and gave them information about the students and did not prevent journalists from entering the campus to accost students. Also, there was a far-right artist that went into the courtyard of the Academy naked and black-faced himself, shouting the N-word several times. It created a massive amount of, I would almost say terror, within the institution, and the students became really afraid. So, everyone was afraid of speaking out because all of a sudden you have the interference of the police; a lot of material being handed to the police. So at this moment, the truth telling was completely shut down. This was very dangerous for the Art Academy and the practice of freedom in its education.

On a final note, I would like to share something that you wrote to me Dalida, about a year ago, which I think captures the liberatory possibilities of working on the thresholds. After the Ph.D. defense of our colleague, Jane Jin Kaisen, who has worked extensively on the shamanic figure of the Princess Bari [3], you wrote:

“I have walked out of academia not once, but twice now. And each time it has felt like crossing a liberatory threshold between the living and the dead, to evoke Bari once again, and it’s not entirely clear who is dead and who is alive – it is shifting, it is both and, and the dwelling at which love for both sides remains important to hold on to. My aspiration is that I can act as a mediator, as Jane evokes, between worlds, and create horizons of possibility for being in doing so…”

I just thought that that was a beautiful response to some of the questions that we have raised today. Even though at the moment I’m mainly on the outside of institutions, but at the same time, I feel that I have never been so much into the academy in terms of my own practice as an artist, researcher and educator. In that regard, I think what is common for our artistic and educational practices is that they emerge as a form of action-based and teaching-based research, in which the liberatory possibilities of transgressing and transforming sedimented practices and categorizations within the academy and society becomes possible – even if it is only for a fleeting moment.

Dalida: Thank you both. Your stories reveal the forms of violence that can exist in art academies, and how they are enmeshed with what we could understand as the modern colonial aesthetic project. Yet, I have been in your classrooms, or pedagogical situations, with both of you, in those very academies. I’ve been side by side with you as you enact radical interventions. I was with you, Isa, for the Plateform Shoes workshop that you organized, which brought together art students from across France in a five day workshop at the Saline Royale at Arc-et-Senans. As a Visiting Artist/Scholar, you asked me to lead students in a workshop. The architecture of the Saline is a perfect panopticon: So my question was, how can we choreograph our escapes from it? Visually, spatially, and sonically? You created that pedagogical potentiality. And I was with you, Katrine, for your Archives That Matter project, a series of interventions related to, as you say, “min(d)ing the archives,” together with artist-researchers from across the world(s) that have been impacted by Danish colonialism. It was also an incredibly important space. Along with the other interlocutors that you convened, I brought to the table my work on contemporary Third Cinema and decolonial aesthetics, and it was wonderful to be in conversation with them, and then later, with your students. I felt such an expansive space to think, breathe, and move, collectively. In both cases, I learned what you both practice in those spaces. You create thresholds. Through this, I know how much freedom you have actually made possible. Although “freedom” sometimes feels so burdened with Cold War ideology – the American democratization and freedom discourse – that it becomes kind of dangerous to me. Perhaps though, this is just another edge that we have to contend with, as a threshold, and we can choose to think with bell hooks’ sense of it: a practice.

The spaces that you both create are liberatory engagements, a consideration of alternatives to what is there, in which people can also recognize their own histories and knowledges that are not valued by formal schooling. So I want to honor the interventions that you have made possible, that I’ve witnessed, as we continue, as companions, on our routes inside, outside, alongside, and across institutions.

This conversation was recorded online on November 15, 2021. The transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

Inside/outside/across/between: Crossing thresholds, academically and otherwise is part of Urgent Pedagogies Issue#5: Pluraversality

1.

hooks, bell. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. London and New York: Routledge, 1994.

2.

Massu, Isabelle, et al. “Teaching To Transgress Toolbox” project. Access at http://www.ttttoolbox.net/

3.

See Jane Jin Kaisen and Anne Kølbæk Iversen, Eds. Community of Parting. Copenhagen, DK and Berlin, DE: Archive Books and the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, in collaboration with Kunsthal Charlottenborg, 2020.

Ph.D., is a visual artist, independent researcher and educator and a member of the Uncertain Archives research collective (University of Copenhagen). Her work explores “reparative critical practices” as collaborative, audio-visual practices that explore the debris of broken histories. Current artistic work and research traverse the entangled colonial archives between the United States Virgin Islands, Ghana, Greenland, India, and Denmark, often presented in video installations, performative presentations, and publications. She was the head of the Institute for Art, Writing and Research at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, where she was also a postdoctoral researcher. She is the co-founder of Sorte Firkant bar & cultural venue in Copenhagen and the newly founded artists’ network Reparative Encounters.

is an artist and educator currently teaching visual culture at the Institut Supérieur des Beaux Arts de Besançon in France. She has taught at the Parsons School of Art in Paris, the San Francisco Art Institute and in several non-academic contexts; with feminists associations, and other cultural and social venues, in France and abroad. Since 2018, she focuses on developing critical pedagogies in art schools. She co-organized in 2020, the “Teaching to Transgress Toolbox,” a European research program for artists, researchers, students, and educators to develop tools to foster inclusive pedagogies in art institutions. She is currently on the CAD+SR Advisory Board.

is an artist and researcher living between Helsinki and Boston. Since 2017, she’s together with Christopher Bratton co-founders of the Center for Arts, Design, and Social Research, a poly-centric laboratory for research and practice focused on emancipatory and decolonial pedagogies. With partners in Brazil, Denmark, Finland, Italy, Kenya, Mexico, South Africa, and the UK; and a group of Senior Researchers and Research Fellows, they have co-organized research convenings, exhibitions, workshops, and publications. Benfield works on decolonial aesthetics and has an MFA in moving image practices from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and a Ph.D. in Comparative Ethnic Studies with Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender, and Sexuality, University of California-Berkeley. Bratton is an artist, filmmaker, and education activist.

Archives that Matter project website: https://tidsskrift.dk/ntik/issue/view/8529/965

Entangled Archives project website: https://tidsskrift.dk/nja/article/view/134220/179166?fbclid=IwAR3Qi_9-SdJrz3d4svdmFnw8SkyAO3hAoEaqEobaanwnxgq1-e3tdtsrfGs

Anonymous Artists’ video & press: https://www.idoart.dk/blog/det-kgl-danske-kunstakademis-grundlaegger-smidt-i-havnen

“The Sinking of a Bust Surfaces a Debate Over Denmark’s Past,” New York Times, February 9, 2021. Access at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/09/arts/design/frederik-v-bust-denmark.html?fbclid=IwAR1G7zxmAM5IFMRD13l-VrrI5kEhRpnCnXhABF5rGUqu5ew9Uf1aZFle6bU

Balance Ton Ecole d’Art (BTEA) Besançon student movement social media account: https://www.instagram.com/balancetonecoledart/

“Aux beaux-arts, les étudiantes ne veulent plus séparer le harceleur du professeur,” Street Press, February 8, 2021. Access at https://www.streetpress.com/sujet/1612782917-metoo-harcelement-sexuel-beaux-arts-etudiantes-professeur-agression-patriarcat-culture

Plateform Shoes website: http://isba-besancon.fr/spip.php?article740